antiAtlas Journal #2 - 2017

International borders, between materialisation and dematerialisation

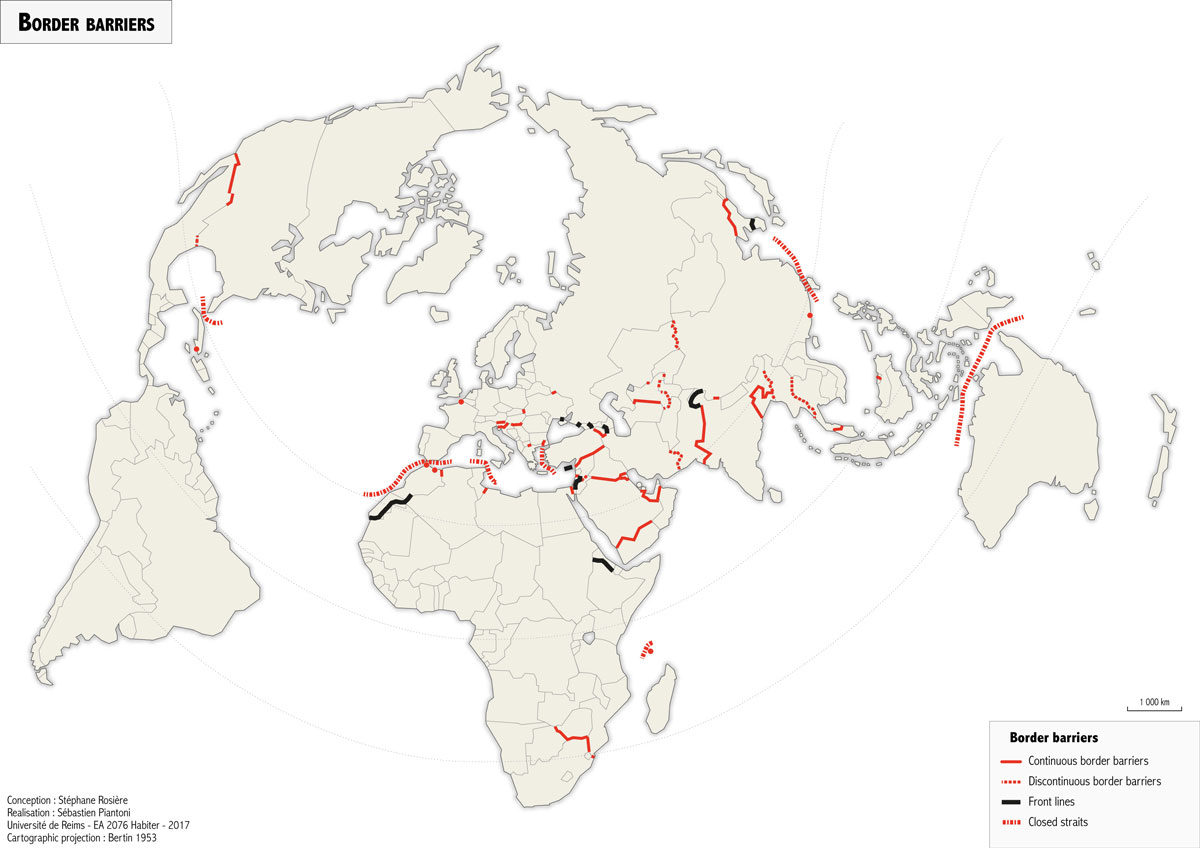

Stéphane Rosière

Stéphane Rosière is Professor at the University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne. He is the director of the Master of geopolitics. He works on polical violence and coercition and has written several articles on contemporanous border barriers. Keywords: Border barriers, international borders, teichopolitics, State, sovereignty, migration.

Planisphère de la liberté de circuler en fonction des passeports. Source : Stéphane Rosière 2017

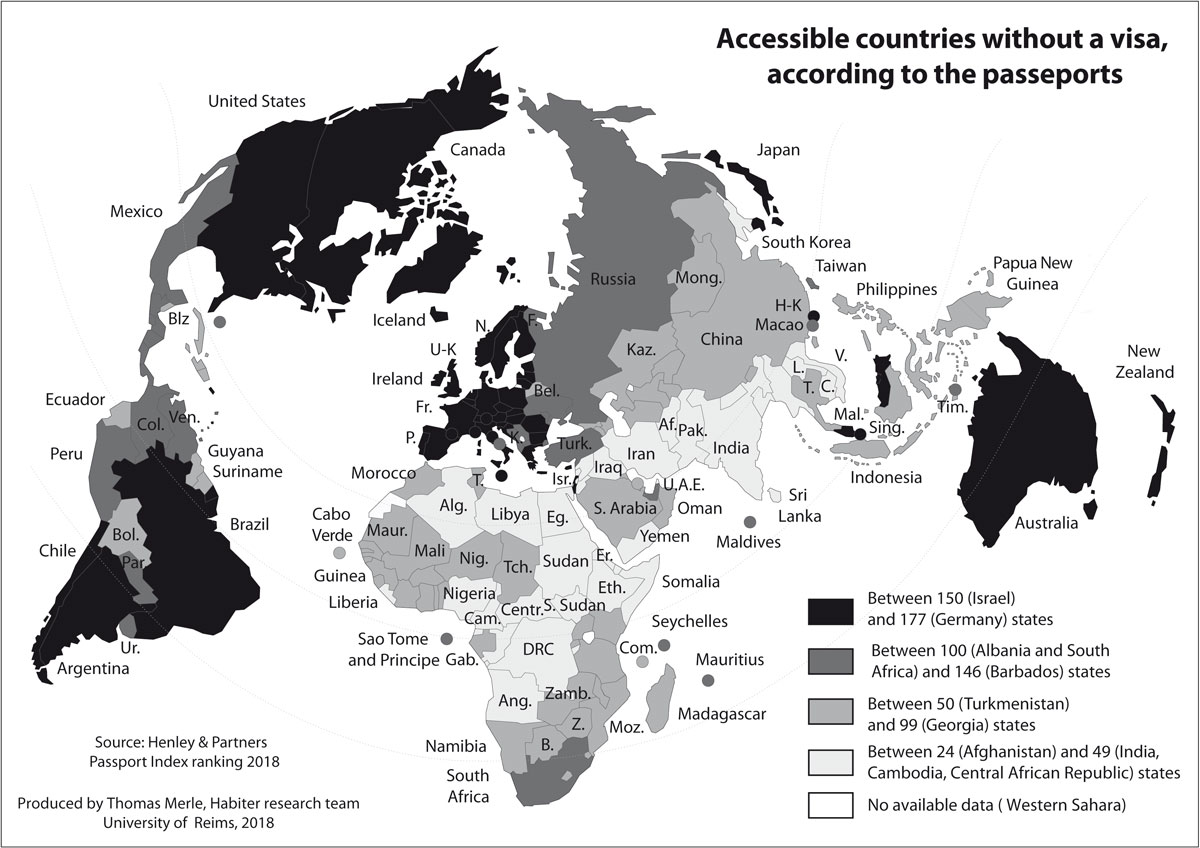

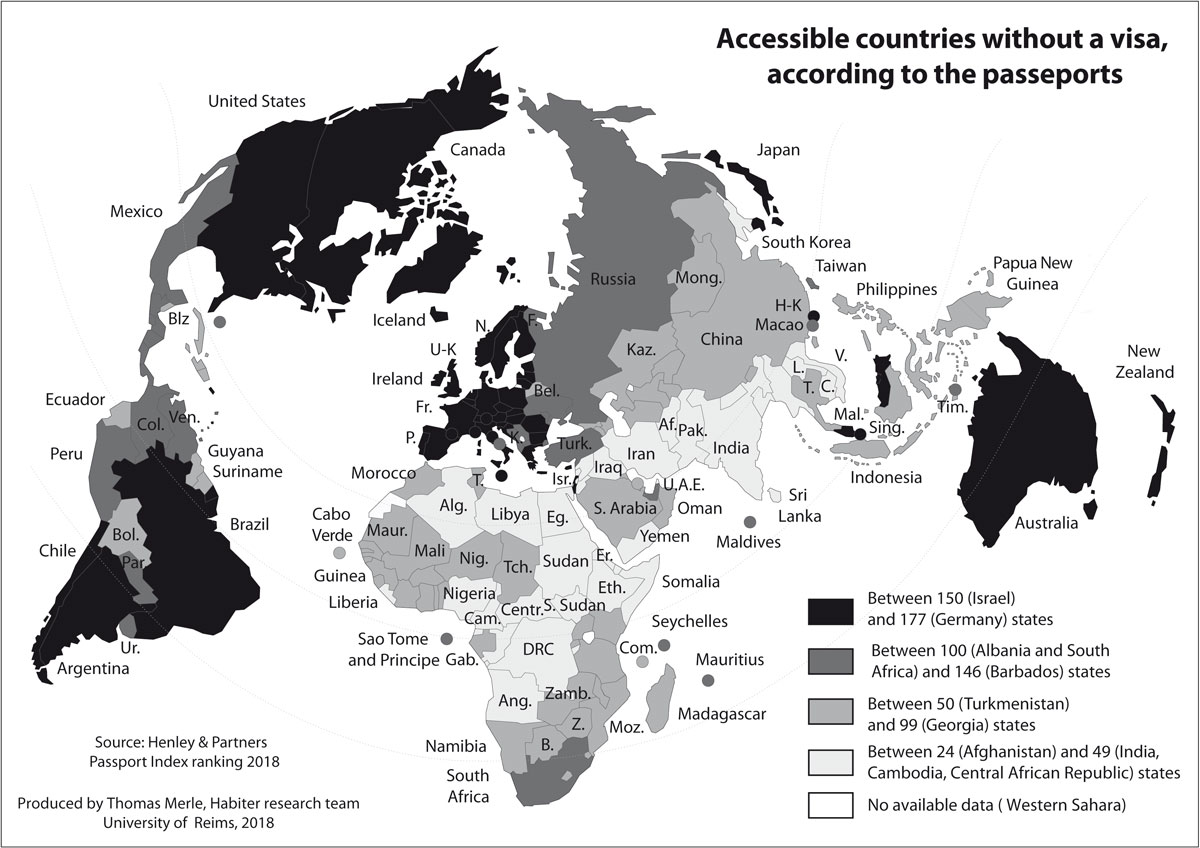

To quote this paper: Rosière, Stéphane, "International Borders, between materialisation et dematerialisation", published on December 10, 2017, antiAtlas Journal #2 | 2017, online, URL : https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/02-international-borders-between-materialisation-and-dematerialisation, Accessed on date.

1Modern times have brought us a slew of contradictory images regarding international borders. First of all, the idea has taken hold that these “major geopolitical discontinuities” (Foucher 1991) are wide open. Under this representation, which was particularly fashionable in the 1990s, borders could be considered something of the past, ultimately doomed to extinction. And yet, little by little, the image of “walls” and other “border barriers” being constructed established itself as another aspect of these lines and underscores states’ resistance to the flows brought about by globalisation (Brown 2009). The paradox linked to the development of these new border barriers has been emphasised for more than a decade (among others, by Andreas and Biersteker 2003, Brown 2009, Ballif and Rosière 2009 and Vallet 2014), and their proliferation during the migrant crisis that hit Europe in 2015 grabbed attention. Reece Jones (Jones and Johnson 2016) recently noted the militarisation affecting these barriers. This article’s aim is to evaluate these seemingly contradictory processes of dematerialisation/materialisation as they relate to international borders. Straightaway, we have to state that the construction of contemporary barriers is but one of the many aspects of “rebordering” (in the words of Andreas and Biersteker 2003), which we will define, broadly speaking, as the increase in border controls. Rebordering includes – but is not limited to – the construction of defensive and protective structures. The process of rebordering is in fact disconnected from border demarcations, which only make up one of the nodes that are monitored, the same as airports, train stations, ports and even the flows’ departure points or transit routes. Rebordering entails the recording, recognition and detection of millions of individuals and large quantities of merchandise. Thus, it requires the development of a worldwide engineering effort that has an impact on all of the world’s territories (Popescu 2012). However, the technological means that are mobilised vary according to the various states’ particular level of development and their position on the global market. To understand this rebordering and its impact on the materiality of borders, we will first of all look at border barriers as a symbol of the unexpected closing of these political lines that were once thought destined to be erased. The construction of these barriers is detached from the level of armed conflict and does not (yet?) affect borders on the whole (1st part). Next, we will show that, at present, one of the important aspects of borders’ materiality is the massive use of technology in monitoring. To this end, we will use the notions of smart borders and virtual fences, which express the temptation of technology in the management of borders, at least in the most-developed countries (2nd part). Finally, we will return to the spread of control linked to cross-border flows in a world marked by the precautionary principle. This spread results in a certain deterioration of the borderline and the proliferation of points of control across the territories. This delinearisation can be regarded as a contemporary mutation of the materiality of international borders (3rd part). next...

I. Very concrete border barriers

2Border barriers are all the structures and devices whose purpose is to prevent international borders from being crossed illegally. These barriers sometimes take the shape of concrete walls (as before in Berlin and today in Jerusalem), but most often they are fences, often reinforced with barbed wire, and sometimes they are virtual, dematerialised fences in the form of motion-sensing devices, without being a physical obstacle (cf. 2). Whatever their morphology, these barriers make it more difficult and more dangerous to attempt to evade or to shield goods from control. Because of their very visible manifestation (especially walls, which are often impressive structures), teichopolitics – a neologism that refers to the policy of partitioning space by constructing “walls” (Ballif and Rosière 2009, Rosière and Jones 2012) – speaks to the desire to control an environment that is viewed as threatening or characterised by security concerns (Vallet, 2014). They could be considered tools to reaffirm states’ sovereignty (Brown 2009). For the record, 33 states (or 17% of the world’s 193 states, as well as four non-recognised territories) have erected and monitor more or less active border barriers or frontlines. They add up to around 20,000 km, or about 8% of the total length of all the borders in the world (250,000 km). Around 60 dyads have installed these devices, whose level of technological sophistication varies from one to the next. Some of the barriers are rather modest in size but carry weight in the media (e.g. Coquelles, where vehicles are loaded onto the train for transfer via tunnel under the English Channel, and the port of Calais), others are much longer and more expensive: The barrier between India and Bangladesh is the longest in the world (approx. 3,300 km), followed by the border between India and Pakistan (2,170 km), which only has one crossing, plus the Line of Control (LOC) of Kashmir, which is 740 km long (these two stretches of border, with two different statuses, total 2,930 km, which illustrates the little-known fact that India’s land borders are among the most heavily monitored and guarded in the world (Jones 2012)), the Moroccan “wall of sand” stretches 2,720 km, the barrier between the United States and Mexico (comprising several sections) measures 1,100 km, and the Eritrea–Ethiopia frontline (a de facto barrier) measures close to 1,000 km. These are major barriers, just like the external border of the Schengen area, which forms a perimeter whose barrierisation is underway, extends over more than 7,000 km and underlines the presence of zones of geopolitical tensions. This relatively recent increase in border barriers illustrates the growing success of “teichopolitics”, which is expressed both along international borders and in urban areas, where there has been a proliferation of closed neighbourhoods or gated communities (Ballif and Rosière 2009).

next...

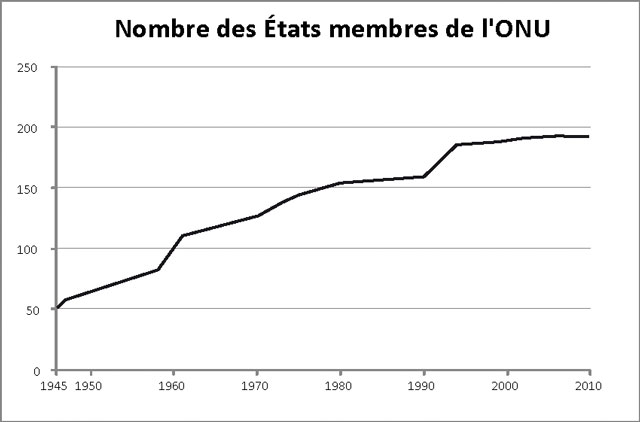

A materialisation that is separate from armed conflict

3The construction of barriers on borders is a response to very different situations. These structures’ goal of partitioning can be linked to military tensions and take the shape of frontlines or ceasefire lines (the DMZ between the two Koreas, the LOC in Kashmir, the Moroccan “wall of sand” in Western Sahara, the barrier in Cyprus etc.). These heavy installations generally prevent any cross-border flows, as by their very nature they make it impossible (although it is possible to make space for them, as in Kashmir or in Cyprus, where there are still pedestrian crossings). These military devices underscore the persistent disputes over the position of certain borders. It is a topic that was buried rather quickly by border studies researchers in the 1990s who believed that the world was opening up and borders were falling (we should note a renewed interest in this topic following the publication of the new encyclopaedia of border conflicts edited by Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly (Brunet-Jailly 2015)). However, these essentially military lines continue to be a minority and represent only a quarter of the total length of barriers in the world. There are fewer and fewer disputes over borders, particularly with regard to their position on the ground. Militarily, they no longer lead to “major wars”, as John Mueller (Mueller 1989) calls them. Since 1945, the general trend has been to recognise borders, although this does not mean that there haven’t been bloody exceptions. This small proportion of barriers built for a military purpose underlines the disconnect between the construction of border barriers and the logic of war. It highlights the general pacification of borders and supports Michel Foucher’s argument that we have entered “a historic phase of border regulation” (Foucher 2007, p. 29). This phenomenon is all the more interesting since it is possible to link it to the remarkable rise in the number of states (Rosière 2012), as indicated by the number of United Nations member states, which rose from 51 in 1945 to 193 in 2011 (cf. Figure 2). “Since 1991, more than 26,000 km of new international borders have been put up, and another 24,000 have been subject to demarcation agreements” (Foucher, 2007, p. 7). The rise in the number of states could have led to full-scale tensions, but it is clearly counterbalanced by the headway that has been made in terms of “border regulation” (the expression used by Foucher). Today, the border length in kilometres that remains disputed is rather small. But the fact that the position of land borders is rarely questioned does not mean they do not pose any problems, particularly with regard to security in society and the control of flows. Most border barriers are erected by states that do not lay claim to their neighbours’ territory and most often even have good diplomatic relations with them (e.g. the United States and Mexico, which form part of NAFTA, or the EU and its partner countries in the European Neighbourhood Policy). From this perspective, barriers can be understood as commonplace (rather than unconventional) management tools. next...

Figure 1. Map of border barriers around the world (Rosière 2017). Source : Stéphane Rosière 2017

Figure 2. The rise in the number of UN member states. Source : Stéphane Rosière 2010

Discontinuous devices

4At present, the technologisation of borders is still a process that primarily affects the most-developed countries. This is true despite the construction of numerous ‘walls’, and, as we mentioned above, barriers make up only about 8% of the total length of borders around the world, which means that more than 90% of borders are not fully marked out (except for markers that indicate the border on the ground but do not close it off in any way). The lack of such “materialisation”, that is, of any kind of continuous fencing, is the outcome of very different situations. The complete absence of materialisation is common in the dyads delineating states that have good bilateral relations and are often committed to a process of regional integration and only separated by borders that have become “transparent” (Rosière, 1998). This is the case, for example, inside the Schengen area. In completely different conditions, many little-developed states do not have the financial means to monitor – let alone close – these boundaries that are often the outcomes of colonisation. The role that topographic conditions play should not be underestimated either. Areas with dunes (ergs in the Sahara), marshes (mangrove on the equator) and dense forests (equatorial, even temperate, forests), as well as (high) mountains, make it impractical to put up barriers. Because of these economic and natural factors, numerous borders have not been constructed (Sahel, Central Africa, Latin America) and sometimes not even been marked out. We should note, however, that there are initiatives (e.g. the African Union’s border programme) whose goal is to mark out these demarcations. A barrier is rarely constructed in desert areas (although the Middle East serves as a counter-example, as there is a barrier separating Saudi Arabia from Iraq); generally speaking, barriers are put up (schematically, at least) so as to be perpendicular to the flows. However, these devices are generally discontinuous and porous. The United States–Mexico barrier has many “holes” – and, like most of these structures, the Israeli security fence does, too. Some situations are difficult to grasp, and the installation of light fences is already a very old reality in agricultural landscapes. However, some border barriers are similar in kind, with the fence being higher than ones for livestock. The Eurasian continent is the most affected by these “light” barriers, which are far from being imposing technological barriers but can create problems for both migrants and wildlife (see Linnel et al., 2016). next...

Figure 3. World map of freedom of movement based on passports. Source : Stéphane Rosière 2017

II. Controls at the borders and its consequences for their materialisation

5The current global context is marked by an increase in all kinds of cross-border flows. Such movements might even be described as the primary feature of globalisation. “Globalisation is the generalised interaction between different parts of the world, with the global space being humanity’s area of transaction” (Dollfus 2007, p. 16) These increasing flows are very changeable, and from this perspective, it seems critically important to distinguish between cross-border flows that are not subject to the same regimes. The flows may be classified into intangibles, raw materials, finished or semi-finished products and, finally, flows of people. These flows fall into a strict hierarchy within the framework of globalisation. Financial exchanges (direct foreign investment, speculative investment etc.) are the only ones that have truly been liberalised. What country is closed to investment? The flows of products (raw materials, finished and semi-finished products) form the most visible part of globalisation, whose symbol would be the container ship. These flows are generally welcomed, they can be differentiated according to regional customs regulations and bilateral or multilateral trade agreements. Compared with these first two categories, human flows are those whose integration into the logic of globalisation is the most uneven. Movement (of human beings) must be distinguished from trade (in products). Within the European perspective, there is a call for people to be able to move as freely as goods. Indeed, the free movement of persons was one of the objectives of the Treaty of Rome (1957) and came to fruition with the entry into force of the Schengen Convention (1995), but this situation is relatively rare; thus, the many free trade areas, such as NAFTA or ASEAN, are by no means free zones. Of course, individuals themselves are in no way a homogeneous category. On the contrary, a relentless hierarchy draws distinctions between individuals and their highly variable mobility potential on the basis of their “desirability” (Didiot 2013). Geographer Matthew Sparke has highlighted the emergence of a business-class citizenship made up of businessmen, graduates and even tourists (Sparke 2006). This category of the world’s population, most often holding Western passports, is the most mobile and truly enjoys seamless mobility. Against this aristocracy of movement, one can dialectically oppose a low-cost citizenship that is poor and undesirable and makes up the legions of illegal migrants and refugees at present. There are many people, often citizens of countries in the South (see Figure 3; citizens from the darkest-coloured states can travel freely in most countries), for whom borders are closed (because of visas, quotas or a pure and simple ban). Border barriers are being created against this marginalised population. An almost Marxist reading of border barriers, based on class divisions instead of real security issues, does not seem far-fetched. Of course, it is a simplification to classify human beings as either business-class or low-cost citizens, as there are poor people in rich countries and rich people in poor countries who go against this general trend, but that does not mean that such a general trend does not exist. This approach to the selection of flows by nationality and standard of living still has to be tackled, but it is a marginal postulate in contemporary literature, which, often and probably in error, emphasises the principle of security (Vallet 2014). next...

Technologisation and militarisation of international borders

6The technologisation of international borders is a major trend that fits into a more general dynamic of the “technologisation of security” applied in particular to the “global mobility regime” (Ceyhan 2008) or a new “international management of populations” (Hindess 2000) Ayse Ceyhan’s “technologisation of security” means that technology is made the centrepiece of security systems (Ceyhan 2008). It is a result of the September 11 attacks, but the roots of this process date back much further, specifically to the United States’ tightening of its southern border. Ceyhan has pointed to the safety equipment brought back from Vietnam and installed on the US southern borders as part of the War on Drugs – the term first used by the Nixon administration that was subsequently revived by Ronald Regan in 1986 (Andreas 2001). The technologies used at the borders are those from the fields of telecommunications, electronics and IT, along with military devices (night cameras, sensors). From this point of view, borders form an interface between civilians and the military and take up more and more space at the heart of the security-industrial complex (Saada 2010), which has flourished since the end of the “major wars”. Strengthening border security by means of “technologisation” means, among others, creating so-called “smart borders” or “virtual fences”. The two are not synonymous but express the hope that technology will respond to present-day challenges. next...

The intelligent border

7 The notion of a “smart border” is used for both administrative and political purposes (the term comes from the Smart Border Declaration of 12 December 2001, which the United States and Canada signed and became a 30-point action plan in 2002). The notion of a smart border is related to the “ideal” border, which would be capable of letting flows pass through and detecting danger or an illicit situation without challenging the fluidity of the general traffic (Salter 2004). With the goal of reducing the contradiction between movement (or the fluidity of the flows) and security, the “intelligent” border relies to a massive degree on technology, in particular electronic and information technology. As a result, the intelligent border could be considered a complex “assembly” of mechanisms, institutions, discourses and practices whose elements are not always coherently arranged (Côté-Boucher, 2008). On the international border, the fundamental objective is to control the flows rapidly and efficiently. The smart border uses all devices that assist in recognising individuals (legal travellers, using border-crossing points, or illegal migrants attempting to cross surreptitiously) and controlling the flows of merchandise, like truck and container scanners (cf. Amoore, Marmura and Salter 2008, Popescu 2012) The symbolic dimension of these electronic barriers should not be ignored. The devices connected to these electronic “walls” seek to intimidate (deterrence policy) or to reassert authority (cf. Brown 2009). The technological “wall” must appear infallible, as the machine is presumed to be infallible. However, the devices that are visible when crossing the border are just the tip of the iceberg of “smart borders”; border-crossing points (BCPs) are linked to powerful databases (in the European Union and North America). One of the features of contemporary BCPs is that they are connected to data centres and form a network with them that is separate from the linear border. The selection made of individuals (detection of fraudsters, search for terrorists etc.) at the BCP is effective only thanks to the existence of this network linking the border police’s computers to powerful (and invisible) databases, which has become vital. All travel documents are listed and theoretically verifiable (identity cards, passports, grey cards etc.), as is the interconnection of border agents with their checkpoints, structured at different scales and linked to other databases. Data networking is essential when using data banks, which in the European Union, for example, are on the rise. In this way, a network of computer networks is set up and plays a role in crosslinking (“reticularising”) and delineating borders. Thus, integrated border systems are generated by firms from the “security-industrial complex” (Saada 2010). In this scheme, the boundary line is not a determining factor. The barrier is essentially used to send individuals to the BCP. In addition, a certain customisation of equipment is necessary, and each state is a special case (radars for maritime areas or deserts are inefficient in densely populated areas). Interestingly, the methods and materials used (e.g. types of fencing and surveillance cameras) are the same around industrial areas and protected sites as on the borders. These systems go unseen. Border integrated management comprises at least three levels (the geographer would call them three “scales”): command control (which centralises information), regional centres and local centres (BCP). All these levels are interconnected and have data centres that might be located far away. The interconnection between these elements is clearly decisive. So, the information from the local centres can go back to the regional centres, which select and, if need be, transmit it to the national centre. The way in which information “trickles down” is also significant. It is technically possible for there to be direct contact between an agent equipped with a mobile link system (laptop) and the different centres. This interconnection plays a pivotal role; it is the network’s strong point but also its Achilles heel. These programmes are usually very expensive. So-called “smart borders” are also mainly reserved for the richest countries (the United States, EU, Israel, Saudi Arabia and Qatar being among the countries that have developed the most ambitious high-tech programmes). The richest countries tend to have these systems, while they are slow to develop in the poorest ones, but there is a clear trend that these devices are spreading. The manufacturers of all these devices are obviously the first to benefit from this spread. next...

The virtual fence

8As we reflect on the (de)materialisation of borders, it is worth examining the notion of a “virtual fence”. The term refers to an invisible border barrier on which surveillance is carried out by devices that link the space adjacent to the borderline in order to detect movement. Virtual barrier technology was originally developed for livestock farmers before they became useful to the military, border guards and customs officers. The use of techniques to manage livestock and then humans is not new. For example, barbed wire was first created for livestock before it was applied to humans (Razac 2000). On some borders, remote sensing plays a key role (radars, thermal cameras and military technologies in general). By setting up a virtual border, decision makers are betting on technology to create an invisible wall that is more efficient than hard devices. One of the first virtual fences ever installed was a test section set up as part of the Secure Border Initiative (SBI) on the southern border of the United States. A 28-mile (17.45-km) pilot stretch was completed by a Boeing-led consortium of companies in the Tucson, Arizona, area at an estimated cost of $67 million. In other words, it cost $3.83 million/km. This project proved to be ineffective (use of sensitive radars on land) and was dropped due to the exorbitant cost. Technology, therefore, has its limits, and traditional techniques (i.e. fences) still appear to have certain advantages. However, other fences have been built. In Europe, Slovakia offers one of the best examples. As a candidate for membership of the Schengen area, Slovakia erected a virtual fence in 2007. It consists of a “chain” of 500 thermal imaging cameras placed at regular intervals along more than 30 km of its border with Ukraine. Virtual fences are rare. For poor countries, the costly technology and the unsuitability because of topography (mountain, forest, marshland, extreme climates and particularly arid deserts) are among the many obstacles that prevent such devices from being installed – unless the flows are too weak given the installation cost (i.e. more than $1 million/km). In fact, the tendency is rather to combine the two types of devices – concrete walls and virtual barriers – in order to maximise the chances of stopping unwanted flows. But unlike the smart border, the “purely” virtual border remains a pipe dream. These virtual borders are expensive and rare; the Slovakia–Ukraine border is the best and basically only example of its kind. next...

Frontière slovaco-ukrainienne. Photographie Stéphane Rosière 2014

Border guards, travellers and machines

9In this context in which systems, supervision and control are connected through machines, the border guard is often an individual who initially looks at a screen and analyses different types of documents or images: images (filmed and/or photographed) that are analysed (thanks to the connection with databases), radar screen, maps, hierarchical communications (waiting for orders): it is complex resource management. For the border guard or customs officer seated behind a screen, the border is often virtual. But for those who cross the border, facing this technology is a relatively concrete deterrent. The individual is evaluated, sifted through different files, and biometric data are tested more and more. Since 2009, all passports issued in France have been biometric. Thus, machines are playing an increasingly important role, and the traveller is subjected to ever more evaluation by machines. Since it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between the “detected elements”, human analysis ultimately makes a difference. This is where the automation of border surveillance is limited, even though it forms part of a major trend. In such a system, it is rather the human being who is dematerialised or reduced to a set of biometric and administrative data... The border (the line, for example, the BCP) becomes one element – or place – among many others in a more general system of monitoring and control. In this system, the privileged contact is not so much between human beings as it is between a human being and a machine perceived as infallible. This is a new materiality of the contemporary border that send us back to all the checkpoints produced by contemporary society. next...

A Hungaro-Slovak border post. Photograph © Stéphane Rosière 2011

III. ‘Security continuum’ and the dissemination of borders

10In the mid-1990s, Didier Bigo (1996) wrote about the existence of a “security continuum” linking the issues of terrorism, smuggling (drug trafficking) and illegal immigration. This continuum interests us as we consider the materiality of borders. It is not only based on a continuity of threats but also endowed with a spatial dimension that blurs the distinction between the border and the territory it defines. Indeed, the problems of the illegal crossing of the border are no longer considered part of border management in the strict sense but as part of more general concerns related to security, and managing it has an impact on the space as a whole and no longer just the borderline. This security continuum is unified by the fight against organised cross-border crime committed by clandestine transnational actors, whom Peter Andreas (2003) defines as all: “nonstate actors who operate across national borders in violation of state laws and who attempt to evade law enforcement efforts” (Andreas 2003, p. 78). Thus, border management is increasingly treated as a fight against insecurity. The security continuum is a continuum of actors, techniques and (legal or illegal) violence and fears. In this continuum, the border is only one element of a larger system; it is simultaneously dematerialised and disseminated. Indeed, borders are characterised by a logic of delinearisation and deterritorialisation that includes crosslinking (or networking) and punctiformisation (structuring as points), as in the case of railway stations and international airports, which, strictly speaking, are often located far from borders. As Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary and Frédéric Giraut point out: “The spatial inscription of the border is increasingly difficult to define: Borders are organised (...) more and more as networks, which has created the idea of reticular borders” (Amilhat Szary and Girault 2011) One can assert that borders are in fact “mobile” (Amilhat Szary 2015), which means, above all, that control is displaced and no longer affects only the borderline. The logic of preclearance illustrates this delineation of border control very well (Côté-Boucher 2010). In this context, the controls (whether it is the control of individuals applying for a visa or of goods destined for export whose characteristics are verified the moment they leave the factory or workshop) happen well before any borderline is crossed. Individuals are controlled in the country of departure or transit (in the consulates or even the airlines, which are considered accountable if they allow people to board without the proper legal documents). In this logic, the border is diluted in space, and its importance must be put into perspective. The erasure (and dematerialisation) of the border is done by sort of spreading the border function, which is consequently delineated. These non-linear devices evaluate the flows (described above) as a whole with a clear focus on controlling human mobility at the heart of concerns, while the distinction between a refugee and a terrorist is often deliberately erased. The notion of the “pixellisation” of the border, or of dissemination, expresses this spreading of border control: Where does the state begin? The notion of the “pixellisation” of the border (Bigo and Guild 2005), or of dissemination, expresses this spreading of border control, and the two authors ask the following question: Where does the state begin? There are numerous examples of this diffusion. Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary (2015, p. 52) recalls, for example, that the European Council gave the go-ahead for the creation of a network of “Immigration” Liaison Officers (OLI) “whose formalised status in 2004 allows intervention (...) in third countries”. For his part, Olivier Clochard (2012) underlines the “spread of places of confinement” on EU territory, given how many places there are now where migrants are held/detained and that are controlled by border police. This dissemination implies maintaining, if not creating, multiple borders... “Designed to facilitate movement, Schengen actually maintains a thousand borders aimed at prioritising internal mobility based on status (European citizen, resident alien, visitor etc.) and controls in border areas and all across the territory” (Clochard, 2012, p. 37). next...

Asymmetric borders and mobility

11A border’s materiality may vary depending on the nature and direction of flows. The same border can be experienced as an impenetrable limit by one and as one without any great significance by another. By studying the US NEXUS smart border programme, Matthew Sparke (2006) has highlighted the asymmetry of flows generated by contemporary border-crossing technologies. The NEXUS programme, established in 2002 on the United States–Canada border (and whose equivalent on the Mexican side is the SENTRI programme) aims to reduce waiting times by selecting flows at BCPs. A Nexus card is made available to North American citizens. The holder exchanges his/her personal data for freedom of movement. Control at the border crossing is automated (man/machine relationship) and similar to what happens at tolling gates on a highway. In this way, the bearer, whose card the authorities consider equivalent to a US or Canadian passport, spends less time crossing the border thanks to an expedited process. At a border station with RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) readers, the information contained in Nexus ID cards is computer analysed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents, and the crossing is normally completed within a few seconds. Others wishing to cross the border have to wait much longer. The essential idea in this border asymmetry is that it is not enough to examine the border itself in order to consider its materiality; it is necessary to correlate the border with the flows crossing it. We can, therefore, see that the same border has a variable permeability that relates to individuals’ passports. The notion of asymmetry (Foucher 2007, Ritaine 2009) expresses this differentiation between flows – a critical part of the processes we describe. Borders are transformed into ‘asymmetrical membranes’ that permit the exit but protect the entry of individuals coming from the other side “Borders are transformed into ‘asymmetrical membranes’ that permit the exit but protect the entry of individuals coming from the other side” (Foucher, 2007, p. 18). The system of devices that constitute the border is therefore deployed in different ways, depending on the nature (hierarchy of flows mentioned above) but also on the direction of cross-border flows (the teichopolitics, which limits entry into protected territories in particular). The discontinuities of development (standard of living), as well as certain cultural boundaries, sometimes generate tensions and teichopolitics. Asymmetrical situations are among the most likely to generate border barriers. “The wall is a unilateral and asymmetrical response to the perception of an equally asymmetrical danger” (Ritaine 2009, p. 157) Far from being exceptions, these asymmetrical situations, including not only crossing borders but also movement in general, have been well described in the Israeli context by Latte-Abdallah and Parizot (2011). This asymmetrical movement tends to become the norm and a feature of the materiality of contemporary borders, which should be considered as obstacles with a variable geometry. next...

Conclusion : (de)materialisation and complex processes

12The processes of materialisation and dematerialisation are conceptually paradoxical, but not in their concrete manifestation in the field. On the contrary, these processes often appear to be complementary. The spread of borders does not prevent the over-materialisation of the borderline. The example of the richest countries even shows us that the two processes are concomitant. Between the dissemination, the invisibility and the reinforced concrete, the materiality of the border must be carefully considered. It seems difficult to assign a degree of (de)materiality to a border because this same object can be characterised by a very different management of flows, on the basis of their nature and their direction. The border system is “reticularised”, the border is only one of the elements in a larger mesh of control, and the border is more and more absorbed by a category of complex objects. The materialisation that takes place as a result of barriers is more and more associated with an all-out extension of control based on partially invisible technologies and intended to control the entire territory (spot checks, identity checks) and not just the borderline. Thus, the border system is “reticularised”, the border is only one of the elements in a larger mesh of control, and the border is more and more absorbed by a category of complex objects. In the 21st century, a good border is no longer an open border; barriers – albeit inevitably circumventable, even at the cost of more and more deaths (a dimension that could be integrated into the materiality of the border but that we have omitted from this short text) – are called for by public opinion as fear of terrorism spreads. The border barrier provides reassurance to a society under siege (in the words of Z. Baumann, 2002). This form of materialisation is not new. Borders have, since ancient times, been marked out, that is to say, made visible. Moreover, unmarked borders produce tension. Thus, the border markers are part of an old approach of necessary and adequate materialisation, creating a pacified borderline because it is accepted by both parties. The border barrier would be a device of the same type: Visible, it is perceived as a security marker in a world of threats and in flux. The barrier, as we have seen, is not an end in itself and includes a complex system of both multiscalar and delineated surveillance. Thus, we do not live in a time in which borders are dematerialising, as the liberals of the 1990s had dreamed, but there is a concomitant process of the materialisation/dematerialisation of international borders. The materialisation of borders is the outflow of a security policy based on a belief in technology and is part of an industrial logic and a symbolic desire for control (and to assert state power). The devices are very varied: While stealthy (invisible sensors, distant databases, for example), they are also sometimes very visible and made to impress. They therefore come from the symbolic and the discourse, and it doesn’t matter how dubious their effectiveness or problematic their cost (especially during an economic slump) might be. The symbolic dimension of these systems is essential, and a border that is completely invisible would be counterproductive (we saw it above with the failed dream of virtual fences). The purpose of these visible and invisible, material and immaterial devices goes beyond the security dimension alone. Is their goal really to stop terrorists? Presumably not in the vast majority of cases. Is it therefore a question of stopping illegal migrants? This goal seems unattainable. The materialisation of borders does not meet official objectives, but it is the fruit born of the congruence of distinct and uncoordinated aims that strive to achieve the same result: producing border devices. Among these aims, we can highlight those of political staff who want to act with an eye towards upcoming elections. But we must not forget the firms in the security-industrial sector that are looking towards vital markets for their survival, as well as the economic actors (entrepreneurs) who are satisfied with the official closure of the borders, which tends to weaken the status of illegal migrants and form a labour force at will – a weakened and globalised “Lumpenproletariat”. As such, the current process of materialising borders is a great indicator of the motivations of many actors with different (and sometimes contradictory) objectives and international tensions linked to transnational flows. next...

Bibliography

13 Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure, 2015, Qu’est-ce qu’une frontière aujourd’hui ?, Paris, PUF.

Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure, Giraut, Frédéric, 2015, Borderities and the Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan UK, 308 p.

Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure, Giraut, Frédéric, 2011, « Frontières mobiles : présentation du colloque BRIT XI », [En ligne] http://www.unige.ch/ses/geo/britXI/index/BRIT_ProgramFinal__.pdf

Amoore, Louise, Marmura, Stephen, Salter, Mark, 2008, « Smart Borders and Mobilities: Spaces, Zones, Enclosures », Surveillance & Society, vol. 5(2), p. 96-101.

Andreas, Peter, Biersteker, Thomas J., 2003, The Rebordering of North America: Integration and Exclusion in a New Security Context, New York/Londres, Routledge, 179 p.

Andreas, Peter, 2003, « Redrawing the line. Borders and Security in the Twenty-first Century », International Security, vol. 28(2), p. 78-111.

Andreas, Peter, 2001, Border games. Policing the US-Mexico Divide, Ithaca, Londres, Cornell Universities Press.

Ballif, Florine, Rosière, Stéphane, 2009, « Le défi des teichopolitiques. Analyser la fermeture contemporaine des territoires », L’Espace Géographique, vol. 38, n°3/2009, p. 193-206.

Bauman, Zygmunt, 2002, Society under Siege, Cambridge, Polity Press.

Bigo, Didier, 1996, Polices en réseaux, l’expérience européenne, Paris, Presses de Sciences po.

Bigo, Didier, Guild, Elspeth, 2005, Controlling frontiers: Free Movement into and within Europe, Londres, Ashgate, 283 p.

Brunet-Jailly, Emmanuel (dir.), 2015, Border disputes: a Global Encyclopedy, Santa Barbara, ABC-Clio, 3 vol., 1218 p.

Brown, Wendy, 2009, Murs. Les murs de séparation et le déclin de la souveraineté étatique, Paris, les Prairies ordinaires, 210 p.

Ceyhan, Ayse, 2008, « Technologization of Security: Management of Uncertainty and Risk in the Age of Biometrics », Surveillance and Society, vol. 5 (2), p. 102-123.

Clochard, Olivier, 2012, Atlas critique des migrations, Paris, A. Colin.

Côté-Boucher, Karine, 2010, « Risky Business? Border Preclearance and the Securing of Economic Life in North America », in Luxton, Meg, Braedley, Susan (dir.), Neoliberalism and everyday life, Montréal, Ithaca, McGill-Queen's University Press.

Côté-Boucher, Karine, 2008, « The Diffuse Border: Intelligence-Sharing, Control and Confinement along Canada’s Smart Border », Surveillance & Societ, vol. 5(2), p. 142-165 [en ligne] http://www.surveillance-and-society.org/articles5(2)/canada.pdf

David, Charles-Philippe, Vallet, Élisabeth, 2012, « Du retour des murs frontaliers en relations internationales », Études internationales, « Le retour des murs en relations internationales », vol. XLIII, n°1, p. 5-27.

Didiot, Marie, 2013, « Les barrières frontalières : archaïsmes inadaptés ou renforts du pouvoir étatique ? », L’Espace Politique [En ligne], 20 | 2013-2, mis en ligne le 18 juillet 2013, consulté le 18 juillet 2016. URL : http://espacepolitique.revues.org/2626.

Dollfus, Olivier, 2007, La mondialisation, Paris, Presses de Sciences-Po, 175 p.

Foucher, Michel, 2007, L’obsession des frontières, Paris, Perrin, 248 p.

Foucher, Michel, 1991, Fronts et frontières. Un tour du monde géopolitique, Paris, Fayard, 2e édition, 691 p.

Gottmann, Jean, 1973, The Significance of Territory, Charlottesville, University Press of Virginia.

Hindess, Barry, 2000, « Citizenship in the International Management of Populations », American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 43(9), p. 1486-1497.

Jeandesboz, Julien, 2011, « Beyond the Tartar Steppe: EUROSUR and the Ethics of European Border Control Practices », in Burger, J. Peter, Gitwirth, Serge (dir.), A Threat Against Europe? Security, Migration and Integration, Bruxelles, Asp / Vubpress / Upa, p. 111-132.

Jones, Reece, Johnson, Corey, 2016, « Border Militarization and the Rearticulation of Sovereignty », Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 41(2), p. 187-200.

Jones, Reece, 2012, Border Walls: Security and the War on Terror in the United States, India, and Israel, Londres, Zed Books, 224 p.

Latte Abdallah, Stéphanie, Parizot, Cédric (dir.), 2011, À l’ombre du mur. Israéliens et Palestiniens entre séparation et occupation, Arles, Actes Sud /MMSH, 334 p.

Linnell, John D.C., Trouwborst, Arie, Boitani, Luigi, et al., 2016, « Border Security Fencing and Wildlife: The End of the Transboundary Paradigm in Eurasia? », PLOS Biology, vol. 14(6): e1002483. http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.1002483

Mueller, John, 1989, Retreat from Doomsday: the Obsolescence of Major Wars, New York, Basic Books, 336 p.

Popescu, Gabriel, 2012, Bordering and Ordering in the Twenty-first Century: Understanding borders, Plymouth, Rowman & Littlefield, 192 p.

Razac, Olivier, 2000, Histoire politique du barbelé, Paris, La Fabrique, 111 p.

Ritaine, Évelyne, 2009, « La barrière et le checkpoint : mise en politique de l’asymétrie », Cultures & Conflits, n° 73, p. 15-33 [En ligne] http://conflits.revues.org/index17500.html

Rosière, Stéphane, 2012, « Vers des guerres migratoires structurelles ? », Bulletin de l’Association de géographes Français, Dossier : Risques et conflits, vol. 89(1), p. 54-73.

Rosière, Stéphane, Jones, Reece, 2012, « Teichopolitics: re-considering globalization through the role of walls and fences », Geopolitics, vol. 17, n° 1, p. 217-234 (DOI: 10.1080/14650045.2011.574653).

Rosière, Stéphane, 2010, « La fragmentation de l’espace étatique mondial », L’Espace Politique [En ligne], 11 | 2010-2, mis en ligne le 16 novembre 2010, consulté le 28 novembre 2012. URL : http://espacepolitique.revues.org/index1608.html

Rosière, Stéphane, 1998, « Contribution à l'étude géographique des frontières : le cas de la Hongrie », Revue Géographique de l’Est, Nancy, tome XXXVIII, n° 4, États et frontières en Europe centrale et orientale, p. 159-168 [En ligne sur le site de la RGE].

Saada, Julien, 2010, « L’économie du Mur : un marché en pleine expansion », Le Banquet, Centre d’étude et de réflexion pour l’action politique (CERAP), n° 27, p. 59-86.

Salter, Mark B., 2004, « Passports, Mobility, and Security: How smart can the border be? », International Studies Perspective, vol. 5, n° 1, p. 71-91.

Sparke, Matthew B., 2006, « A neoliberal nexus: Economy, security and the biopolitics of citizenship on the border », Political Geography, vol. 25, n° 2, p. 151-180.

Vallet, Élisabeth (Ed.), 2014, Borders, Fences and Walls: State of Insecurity?, New York, Ashgate, 298 p. suite...

Notes

1. States or entities that have constructed at least one border barrier: Abkhazia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Botswana, Brunei, Bulgaria, China, Costa Rica, Cyprus (United Nations), Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, France (Calais), Greece, Hungary, India, Iran, Israel, Kenya, Korea (United Nations), Kuwait, Morocco, Nagorno-Karabakh, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, South Ossetia, Spain, Thailand, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United States and Uzbekistan.

2. By “regulation”, we mean an end to litigation over the position of the border.

3. Matthew Sparke didn’t use the expression low-cost citizenship, which the author has created here through deductive reasoning.

4. Available online on the White House website, URL : http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2002/12/20021206-1.html

5. These databases include: the Schengen Information System (data processing system integrating, among other things, the personal data of Schengen Visa applicants and, since 2006, their biometric data or data regarding non-admission or travel restrictions); EURO DAC (system to record the fingerprints of asylum seekers); VIS (data on persons applying for a visa); EUROSUR (network to exchange information on external borders with a problematic ethical dimension (Jeandesboz 2011)), SEA (general registration system for EU entry and exit from EU territory set up in 2013 and in which more 170 million individuals have already been registered); and EU PNR (registration of air traveller data by airlines).

6. The SBInet page on Wikipedia. Accessed on 1 March 2011. URL: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SBInet. Detailed information is available on the website of the US administration’s Government Accountability Office (GAO).

7. In Slovakia, the Swedish firm Ericsson has set up a technical and physical control system for the Ukrainian border (97 km). The "chain" of 500 cameras is mainly installed on the southern part of the dyad (the mountainous north is less supervised, the mountain acts as a natural barrier). Fences are rare and located only near roads.

8. See on this subject the very explicit cover of the book edited in France by A.-L. Amilhat Szary and F. Giraut (2015).

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/02-Rosiere-international-borders-between-materialisation-and-dematerialisation.pdf