antiAtlas Journal #2 - 2017

SoundBorderscapes: Lending a critical ear to the border

Elena Biserna

Elena Biserna is a researcher at Locus Sonus, ESAAix, PRISM. Her interests focus on sound art and contextual practices in relation to urban dynamics, socio-cultural processes and the everyday.

Key-words: borderscape, soundscape, field recording, sound art, acoustemology, border, listening, Justin Bennett, Jacob Kirkegaard, WR, Ultra-red, Lawrence Abu Hamdan

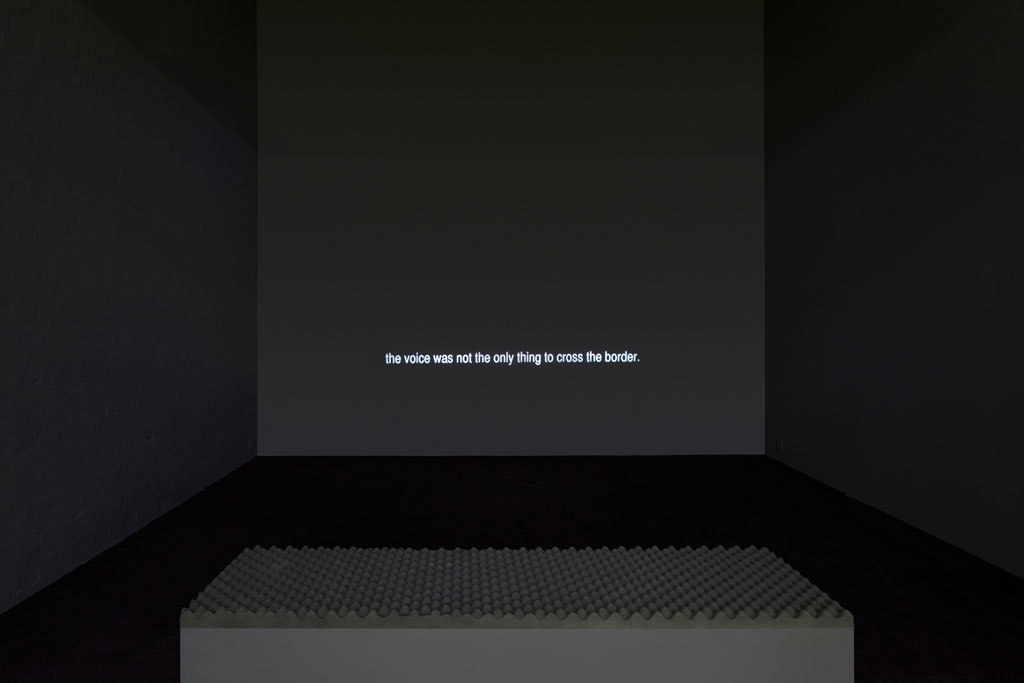

WR, Border Sounds, 2001.

To quote this paper: Biserna, Elena, "SoundBorderscapes: lending a critical ear to the border", published on December 10, 2017, antiAtlas Journal #2, 2017, Online. URL : https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/02-soundborderscapes-lending-a-critical-ear-to-the-border, accessed on date.

I. Introduction: borderscapes and soundscapes

1The term “borderscape”, which first appeared in the field of art and was subsequently taken up by various writers in academic literature, encompasses a complex, process-based and multifaceted conception of the border. First and foremost, the term implies a mobile and temporal notion of the border – a reality that is in the process of becoming and is changing in space and time. According to the definition by Chiara Brambilla (2015, 5), it is a non-static but fluid and fluctuating space formed and traversed by a plurality of bodies, discourses, practices and relationships that reveal continuous definitions and reconstructions of divisions between the inside and the outside, citizen and foreigner, host and traveller, through multiple national, regional, racial and symbolic borders. Second, the term refers to the ways in which the border is perceived, to the visual, narrative and performative representations of how its meanings and effects are assembled (Strüver 2005) and to its culturally constructed nature. The term “soundscape”, introduced by Canadian musicologist Raymond Murray Schafer (1977), covers “the sonic environment which surrounds the sentient” (Rodaway 1994, 83) – an environment that is always dynamic, temporal and relational, created and recreated in the listening experience. Thus, this term also underpins an ecology: a relationship between subject and context. Justin Winkler, for example, defines it as “the totality of the sounds surrounding us, insofar as it can be perceived as a percettema, a perceptual object referring to a subject” and distinguishes it from the “acoustic field” – “the acoustic-physical space of an object” (Winkler 2001, 18). Both terms, then, emphasise the dynamism, fluidity and multiplicity of reality. They focus on the latter’s ontology, which is neither static nor natural but complex and cultural, continually defined and redefined by a constellation of practices and discourses. In other words, they both highlight the key role played by the (individual and collective) subject in the production, definition and materialisation of reality. next...

2Starting from these analogies, in this text I will introduce the term “soundborderscapes” to explore a series of projects that engage with geo-political borders through sound and listening. This article proposes a critical approach to field recording, soundscape composition and, more generally, sound arts in order to underscore their epistemological and political potential, integrating the aesthetic and phenomenological perspectives that have often dominated debates in this area. Above all, it is about recognising the potential of the microphone to “give voice” to these contested territories and to make the conflicts and the processes taking place at the border (or the border itself as a process) heard. It is also a matter of questioning the traditional interpretation of the border as a line of separation between different entities by using listening as a critical methodology. Ultimately, it is a question of suggesting an “acoustemology” (Feld 1982) of the border in order to reconsider the dichotomies between interior and exterior, belonging and otherness, and inclusion and exclusion, which are at the heart of this concept. next...

II.Recording (at) the border

3Several artists have explored border areas between states through field recordings. The decision to record (at) the border is neither transparent nor neutral. On the contrary, this choice makes clear the artist’s involvement in a spatiotemporal apparatus that is saturated with cultural, social, economic and political issues. Recording (at) the border means, first of all, choosing a specific position, a listening point, exploiting the microphone’s (metaphorical and literal) ability to amplify in one of the places where contemporary conflicts are particularly apparent in order to make them heard. This choice leads us to question the transparency of field recording in order to reveal most clearly its status as an active and subjective practice of framing (and thus, constructing) reality and its critical potential. In Europa (2001–2003), the artist Justin Bennett started a utopian project of sound mapping of the European borders by making recordings of the wastelands between the Schengen countries – areas that have often been abandoned, and where most of the control functions at the border no longer have any reason to take place. As the artist explains: “These places often had very interesting soundscapes. One can hear everything that happens, but at a greater distance that creates a very intriguing sense of emptiness and silence” (Mannucci 2004). The project is based on a series of ambient recordings and other recordings made with contact microphones placed on the fences that sometimes still remain on the ground in the former border areas. Using these recordings, Europa has taken different forms: initially an installation, then a CD, an online radio project and a limited-edition publication. In the version made at the CCNOA–Center for Contemporary Non-Objective Art in Brussels in 2002, the different recordings were activated in real time by an automated programme that used drawings of Europe’s borders as a score to mix and spatialise sound, thus creating an immersive and continually changing installation (Fig. 1 & 2). These recordings were then published in a stereo version on a CD. When listening to them, it is possible to hear natural sounds and sounds of human activity in the distance commingling with the vibrations generated by the movement of the wind on the fences – echoes of the material separations between the countries (Tracks 1 & 2). The result is a spectral soundscape that lacks any human presence but is highly constructed: a “sort of portrait of the sense of emptiness”, according to the artist (Mannucci 2004). While accepting the impossibility of mapping the borders of an expanding Europe in their totality, the artist emphasises the abandonment of these zones by making these material structures, which are still visible and physically present even though they have been emptied of their functions and uses, resonate. next...

Fig. 1: Justin Bennett, Europa, Border 1, 2006, archival inkjet print on paper. 21 x 28 cm edition of 3.

Fig. 2: Justin Bennett, Europa, Border 4, 2006, ink jet impression on paper, 21 x 28 cm.

Justin Bennett, Europa, Track 2 & 4, 2006.

4The mechanisms crystallising borders and their materiality are also addressed in Through the Wall, an installation made by Jacob Kirkegaard in 2013. The border that this project explores is the one that most directly and dramatically conveys an image of separation and material exclusion produced by a physical barrier: the border between Israel and Palestine. Kirkegaard made a series of field recordings around Bethlehem along the system of barriers that Israel had erected in the West Bank after the second intifada. Originally presented as a temporary defensive measure in response to a security emergency – and despite rulings by the United Nations and the International Court of Justice in The Hague, which have considered it a violation of international law – the wall has gradually been “normalised”, becoming the de facto border between Israel and the Palestinian Territories. While Israel considers the barrier as a means of protection against Palestinian terrorism, in Arabic the wall is called jidār al-faṣl al-ʿunṣūrī, which translates as “wall of racial separation” or “apartheid wall”. In an effort to “listen to the wall, and to both sides of it, to hear what the wall itself has to say” (Kirkegaard 2015), the artist recorded on both sides of the barrier, close to its surface, by using both ambient microphones and sensors fixed against the concrete wall to detect its vibrations. While attempting to reach the same spot on both sides of the wall, Kirkegaard was confronted with its physical existence, the obstacles linked to his transit through checkpoints and the intimidating presence of watchtowers. These difficulties, as the artist writes, “emphasised the feeling of separation, alienation and forced isolation the wall creates” (Kirkegaard 2015). This feeling of separation and isolation is also emphasised in a series of photographs that the artist took during his exploration depicting the wall and Israel’s defensive structures from up close (Fig. 3 & 4). However, if we listen to the recordings, what emerges is a completely hybrid soundborderscape whose varied polyphony goes beyond any feeling of demarcation and division. It is a soundborderscape in which the constant presence of the low frequencies of the wall’s vibrations intermingles with the sounds of passenger vehicles or a muezzin’s call to prayer (adhan) from a minaret in the Palestinian Territories. In other words, from an auditory point of view, the wall becomes porous, permeable and resonant – a membrane that makes it possible for the soundscapes of the territories it seeks to separate to filter through. The project’s title, Through the Wall, directly evokes the notion of crossing and of transmission, and this sonic “dematerialisation” of the border is further strengthened by the layout of the installation: a wall with a series of speakers broadcasting the recordings without any indication of which side of the wall they were made on (Fig. 5). In this way, the project deconstructs the materiality of the wall and underlines its constructed and polymorphous nature and, in particular, its penetrability and its openness to being crossed. next...

Fig. 3 : Jacob Kirkegaard, Palestine 2013. Photograph Jacob Kirkegaard.

Fig. 4: Jacob Kirkegaard, Palestine 2013. Photograph Jacob Kirkegaard.

Fig. 5: Jacob Kirkegaard, Through the Wall, ARoS Art Museum, Aarhus, Danemark, 2017. Photograph Jacob Kirkegaard.

III. Composing the struggles on/at the border

5In other projects, recording and amplifying the border take on a more explicitly militant dimension, and the microphone and mixing console are used as tools for political involvement. In these cases, “giving voice” to the border dynamics and making them heard becomes a practice of dissensual politics in the sense proposed by Jacques Rancière: a practice that “makes visible what had no business being seen, and makes heard a discourse where once there was only place for noise” (Rancière 1999, 30). Here, in fact, the microphone is directed at the conflicts taking place at the border, “those struggles that take shape around the [...] unstable line between the ‘inside’ and the ‘outside’, between inclusion and exclusion”, as Mezzadra and Neilson put it in their book, Border as Method (2013, 13). By revealing the conflicts at/on the border and making them heard, these projects use field recording and soundscape composition as a political act whose aim is to disrupt – to deconstruct through listening and resonance – the apparatus that materialises the dichotomy between inclusion and exclusion and thus the ways in which roles are distributed in the political community. next...

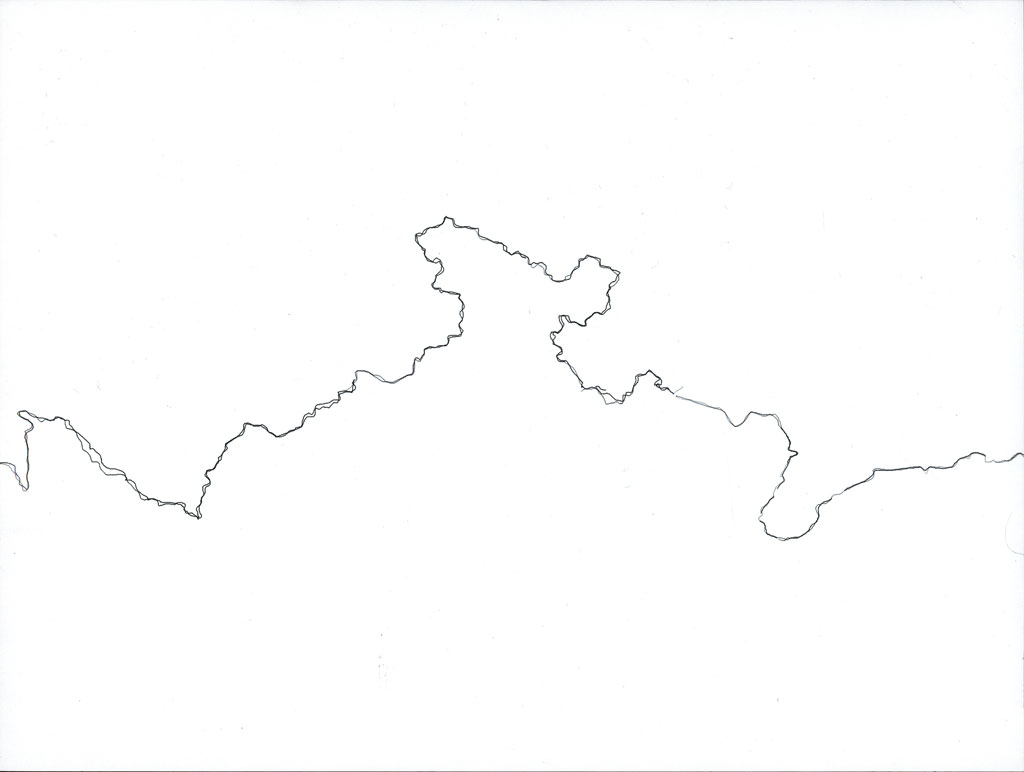

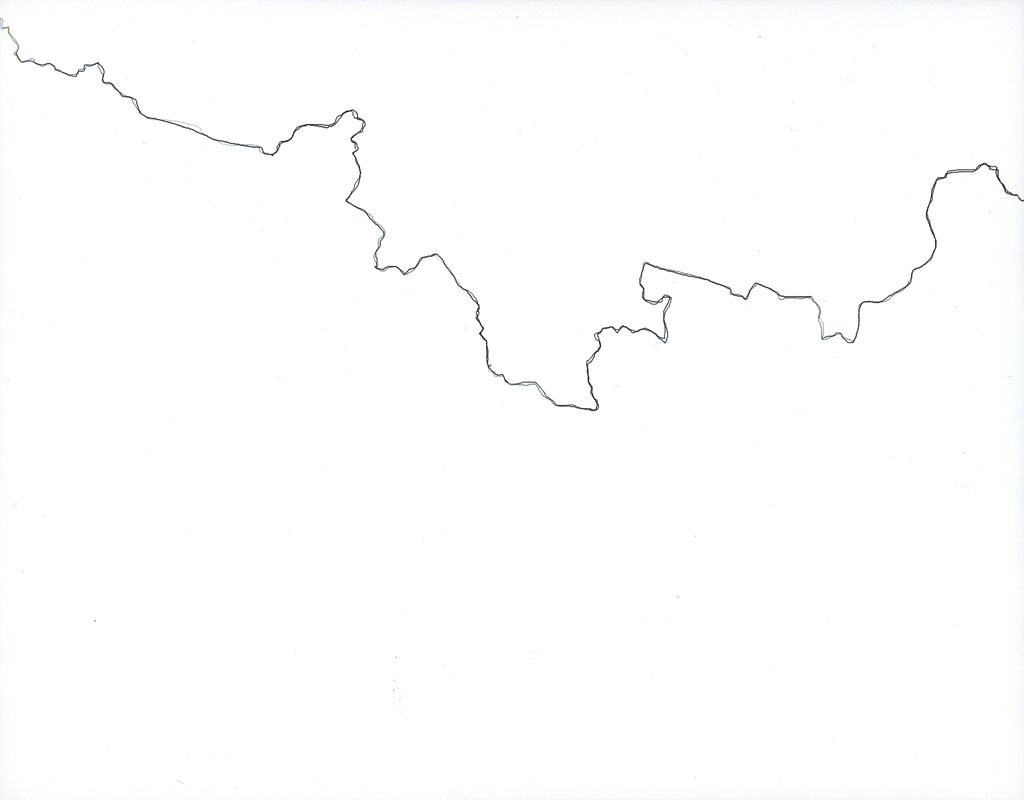

6In July 2001, the WR collective started a five-week journey to map the eastern border of the European Union as part of the NO Border, NO Nation campaign of the NOborder caravan network, an international network that brought together organisations and collectives engaged in protesting against the reinforcement of migration controls and in actions favouring the freedom of movement. Starting in Genoa with that year’s G8 protests, WR travelled eastwards while staying as close as possible to the borders, passing along the Adriatic coast, crossing the Italian–Slovenian border at two points (Gorizia-Nuova Goriza and Lazaret) and continuing towards the north along the Austrian–Slovenian, Austrian–Hungarian, Austrian–Slovak, German–Czech and German–Polish borders (Fig. 6 to 8). On this trip, called Border Sounds, WR collected field recordings but also met with and interviewed a variety of individuals who live, work or campaign on (or are subjected to) the border: activists, ordinary residents, politicians, servicemen, border agents, detention centre operators, migrants and representatives from human rights organisations. These voices give life to the European soundborderscape as it looked like in 2001, creating a multi-voiced account of the (heterogeneous, polysemous, conflictual) experience of the border. The recordings were presented as part of a radio project on Kunstradio, used in a sound film entitled The Voice (2001) and finally composed into an album published by the label Public Records in 2005 (that is, after the borders of the European Union had already expanded to integrate some of the countries explored in Border Sounds). In this version, the recordings are composed into 24 tracks. The first tracks mix field recordings of the G8 protests in Genoa with extracts from Italian television news broadcasts, the soundscape of the city’s Armando Diaz School and the activists’ voices. Gradually, as the album progresses, different sea, urban and rural soundscapes are inhabited by voices recounting various experiences of the border: stories of swimming across the Italian–Slovenian border, the testimony from the mayor of Nuova Goriza describing the porosity of the line that separates it from Gorizia or the operators of the detention centre in Ljubljana talking about the hostility among the area’s residents (Tracks 3 to 6). Practices of control and transgression, of regulation and violation expressing the border’s primary tension between “border reinforcement” and “border crossing” (Vila 2000). next...

Fig. 6 : WR, Border Sounds, 2001.

Fig. 7: WR, Border Sounds, 2001.

Fig. 8: WR, Border Sounds, 2001.

Audio tracks, from top to bottom: - WR, Lazaret Bay, Slovenia. Southern Terminal Adriatic Sea. Border Sounds (Public Record, 2005). - WR, Nova Gorica / Gorizia, Slovenia / Italy. Border Sounds (Public Record, 2005). - WR, Interview with the mayor of Nova Gorica. Border Sounds (Public Record, 2005). - WR, Detention Center, Ljubljana, Slovenia. Border Sounds (Public Record, 2005).

7Published in 2002 by the Ultra-red collective, La Economia Nueva (Operation Gatekeeper) is characterised by an approach to composition that is much more linked to glitch, electronic and ambient music. Formed in the United States in 1994 within the framework of the AIDS campaigns, Ultra-red has continued, over the years, to explore the connections between art practice and activism by uniting different artists, researchers and activists around various kinds of interdisciplinary projects, all of which are rooted in the fight against racism and capitalism or centred on participatory planning, public housing, labour or education. According to the group, “exploring acoustic space as enunciative of social relations, Ultra-red take up the acoustic mapping of contested spaces and histories utilising sound-based research (termed Militant Sound Investigations) that directly engage the organizing and analyses of political struggles” (Ultra-red). For Ultra-red, soundscape is a space that expresses the social sphere’s contradictions and conflicts – a “soundscape of struggle”, as they define it (Ultra-red 2008, 5). Thus, recording becomes an analysis tool based on listening contributing directly to the processes of organising new forms of political subjectivity. next...

8The group has addressed migration issues in several works, but La Economia Nueva is their first project of acoustic mapping of border struggles. The album’s four tracks are entirely composed from field recordings made at the U.S.–Mexican border, at the Saint Ysidro Port of Entry (the largest of the three access points between San Diego and Tijuana) on 10 December 2000, during the demonstrations against the border enforcement measures called Operation Gatekeeper. Launched in 1994 – the same year the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) came into force, and thus, when trade between Mexico, the United States and Canada was liberalised – Operation Gatekeeper developed a series of control mechanisms: a system of physical barriers, underground sensors, new checkpoints, the first immigration court at the border, a system of biometric identification and, for all intents and purposed, its complete militarisation. In this framework, the operation has become a case in point of the contradictions between the increasing liberalisation of the flow of goods, capital and labour in the global landscape and the concomitant strengthening of protective measures against illegal immigration. In other words, it is an example of the selection, filtering and differentiation that, as many researchers have pointed out, have become the primary functions of the border today (Balibar 1994, Popescu 2012, Parizot et al. 2013, among others). Mezzadra and Neilson, for example, argue that “borders, far from serving merely to block or obstruct global passages of people, money, or objects, have become central devices for their articulation” (2013, ix) – an articulation that is determined, in large part, by the reasons of global neoliberalism. In La Economia Nueva, Ultra-red explicitly take on these contradictions by composing or “organising” a “soundborderscape of struggle”. Thanks to all the mixing console’s sound processing functions, the pieces develop sonic textures that are both dense and rarefied. On the first track, low frequencies gradually make way for percussive sounds, repetitive rhythms and voices that articulate, in both Spanish and English, individuals’ and groups’ positions on Operation Gatekeeper and the right to freedom of movement. The second piece, Movimiento II (Track 7), is characterised by a metallic percussive rhythm that indicates the presence of physical barriers by making them reverberate. Less referential and narrative than Border Sounds, the album creates a more indirect but no less explicit relationship with the economic and political conflicts on/at the border through listening, recording, manipulating and organising sound. In so doing, Ultra-red rely on some of the techniques and terminology of the musical avant-garde – in this album, the techniques of electronic music and glitch in particular – but shift them on political grounds. In the 1940s, dissatisfied with the restrictive notion of music, Edgard Varèse broadened the term’s definition by introducing the expression “organised sound” (1983, 56). This definition was subsequently taken up by John Cage in his text The Future of Music: Credo (2004), but what was at stake was still the definition of music, of its materials and instruments. For Ultra-red, by contrast, the organisation of the sonic field is only the first step for the organisation of listening – listening interpreted as a relationship with others and with the world. Therefore, it has the potential both to lay the foundations of an “analysis in action” (Ultra-red 2012, 3) and to “contribute significantly to the construction of collectivity” (Ultra-red 2012, 4). next...

Track 7: Ultra-red, Movimiento II. La Economia Nueva (Operation Gatekeeper) (Fat Cat Records, 2002).

IV. Voiceborderscapes

9The conflicts that define the very nature of the border are also invested in Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley (2013) by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, an artist who on many occasions has addressed the stakes of control and surveillance systems, as well as the processes of exclusion and inclusion in contemporary society, by examining legal practices related to listening, sound identification technologies and the legal status of voice and language. These topics are also at the core of this audiovisual installation that explores the oral border between Israel and Syria and, in particular, the area of the Golan Heights, which Israel annexed during the Six-Day War (1967) and, de jure, still belongs to Syria (Fig. 9). Language Gulf in the Shouting Valley questions this disputed borderscape by focusing on the vocal practices of the Druze – an ethnic group that follows a heterodox religious doctrine originally derived from Shiite Islam and resides in Lebanon, Syria, Israel and Jordan. Considered to be heretics by Muslims and subject to persecution since the 11th century, the Druze embody this area’s cultural and identitarian border by manifesting, in a particularly contradictory manner, a double movement between exclusion and inclusion, and between belonging and otherness. On the one hand, this community has often mixed with the states in which it lives by participating in their public life. On the other hand, it maintains a minority status, often formally acknowledged by the countries of residence, and a strong sense of transnational identity that transcends the borders between states. In this installation, the Druze’s liminal identity – neither Muslim nor Jewish, citizens but “foreign”, both internal and external – becomes a metonymy for the border’s complexity. suite...

Fig. 9: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Language Gulf In the Shouting Valley, 2013. Exhibition view at Kunsthalle St Gallen.

10The video (Video 1) alternates long black sequences with short fragments of flickering, low-fi images showing one of the vocal practices of the Druze at the border, in the “Shouting Valley”. In this region, the Druze community was divided up after the Six-Day War, following Israeli occupation, and entire families continue to live on either side of the border. Until recently, with the advent of the Internet, the residents had no way of communicating other than through a very particular vocal tactic, which gave the valley its name: going to the valley and shouting, sometimes with the help of a megaphone, in order to project one’s voice beyond the barriers, reach the other side and thus reunite separated families. The video documents these moments of transnational communication in which the personal becomes public, and the voice is used as a means to transgress the restrictions that are sanctioned by the border. The soundtrack plays a foreground role in the economy of the installation. Here, the recordings of these encounters are edited together with an interview conducted with Lisa Hajjar – a specialist in sociology of law and international studies, who has long been working on human rights, torture, conflict and, in particular, on the system of Israeli military tribunals in the Palestinian Territories. The sociologist’s testimony further complicates the perspectives on the Druze as she describes how, because of their bilingualism, Israel has systematically used them as translators in military tribunals during trials against the Palestinians. Regarded as “non-Arabs” and “non-Muslims”, the Druze have been identified as allies of the state in one of the most important institutions to keep control in Palestine. For their part, the Druze demonstrate their loyalty to Israel by showing hostility towards the defendants and offering incomplete translations at trial. During the sociologist’s testimony, the flickering images constantly haunt the screen. Only at the end of the video do we realise that these images actually document a very special day in the “Shouting Valley”. An increasingly distorted voice-over informs us, in Arabic, that on 15 May 2011, the anniversary of the Nakba, a protest on both sides of the border turned into its transgression, and about a hundred Palestinian demonstrators entered Israel from Syria. At the same time, we hear a more and more restless voicescape in the shape of shouts pleading the protesters to stop and reminding them of the presence of mines, along with howls and whistles as they cross, with slogans sung in many voices. As the same narrator says, whether in the “Shouting Valley” or in the Israeli military tribunals: Druze’s bodies inhabit the border, and it is their voice that becomes a mode of affirming, negotiating and sometimes transgressing it. In the courtroom, it is the bilingual voice of the interpreter that becomes the frontline between Palestine and Israel. The interpreter’s purely vocal border enforces the domination of Palestinians by filtering their speech, allowing the minority of their words to pass into audibility while silencing the rest. And, in the Golan Heights, it is through the voice of the Druze that the Israeli/Syrian divide is made distinctly audible. Therefore, in this project, the border is conveyed as a complex voiceborderscape, simultaneously reinforced and crossed, materialised and transgressed by the Druze’s vocal and linguistic practices. Between reduction to silence and amplification, between strategies of control and tactics of resistance, the voice of the Druze embodies an (internal and external) border as a contradictory process engendered by multiple power relations. next...

Video 1: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Language Gulf In the Shouting Valley, 2013, 3 min excerpt.

V. Listening to the border

11Sound is pervasive – it spreads through space and fills it up – and by its relational nature it affects every body it encounters in a vibratory process by making its boundaries osmotic and its demarcations malleable. Sound is neither an object nor the feature of an object but is produced by the relations and interactions between contexts, objects and subjects (O’Callaghan 2007). This intrinsic relationality is linked to the material, vibratory nature of sound: its capacity to generate energetic and tactile exchanges, engender a radical permeability and pass through spaces by spreading from one body to the next, from one material to another. As Roberto Barbanti highlights, “the vibratory-acoustic event, the context in which it occurs and the perceiving subject form a unit and ‘constitute’ the perceived sound in its irreducible duration” (2004, 95). In this way, the auditory sphere is subject to laws that are profoundly different from those of the visible sphere – laws that contradict and up-end deeply entrenched dichotomies in Western thinking. In this regard, sociologist Michael Bull argues: The auditory – in the hierarchy of the senses in the Western world – ranks after sight, and yet it manages to trouble the visually inspired epistemologies that we take for granted: the clear distinction between subject and object, inside and the outside, self and the world (Bull 2005, 112). It is precisely these epistemologies, which can be traced back to Descartes, on which the modern and traditional notion of the border was modelled, constructed and represented. An idea of the border as a stable dividing line between two different territorial entities that is crystallised in a particularly explicit manner in the material separations between countries: walls, gates, fences. While contemporary Border Studies have far exceeded this linear, fixed representation of the border (and the notion of borderscape underscores this shift very clearly), auditory knowledge excludes it a priori because it is based on ubiquity, immersion, becoming, diffusion, vibration, transmission and resonance. Sound – an inherently mobile and wandering figure –, constantly transgresses limits, crosses barriers and calls monolithic identities into question. Listening generates 360 degrees of spatial knowledge – without a centre and a periphery, always embodied, situated, experiential, affective – and conveys information not only about the nature of phenomena but especially about their relationships, their becoming in time and space, their plurality. Therefore, from the perspective of listening, borders – even when they take the form of a wall or a fortified barrier – become a flux in becoming, engendered by a chain of events in reciprocal interaction with each other. From the Druze’s vocal tactics to the resonances of a metal fence, the soundborderscapes created by the artists deconstruct the dualism between the inside and the outside to offer an “image” of the border as a membrane constantly penetrated by the other’s crossing and, at the same time, articulated, constituted and transgressed by a multitude of practices, events, discourses and relations. In this way, they not only amplify and “make audible” the processes that take place at the border – or the border itself as a process – but also propose listening as a useful instrument for a critical epistemology of the border. next...

12In a conversation dealing with subjects that might seem very far removed from geopolitical borders, artist and theorist Brandon LaBelle wrote to me: “a self defined in terms of sound, for me, is the beginning of resituating the inside and the outside, and the lines between who is in and who is out” (Biserna and LaBelle 2016, 279). Listening to the border, then, could be considered a tool for questioning and challenging the oppositions between belonging and otherness, inclusion and exclusion, and the distribution of roles that are associated with these categories; a tool for rethinking it in a way that is not dualist but complex, dynamic, performative, contingent, plural and relational. next...

Bibliography

13

Balibar, Etienne, 1994, “Qu’est-ce qu’une ‘frontière’ ?”, in M.C. Caloz-Tschopp, A. Clevenot and M.P. Tschopp (eds.), Asile, Violence, Exclusion en Europe. Histoire, analyse, prospective, Geneva, Section des Sciences de l’Education de l’Université de Genève, p. 335–343.

Barbanti, Roberto, 2004, “Meccanicismo e determinismo: Ovvero come lo sguardo, fissandosi sulle cose, ha prodotto una visione del mondo riduttiva”, in Antonello Colimberti (ed.), Ecologia della Musica. Saggi sul Paesaggio Sonoro, Rome, Donzelli.

Biserna, Elena and Brandon LaBelle, 2016, “From the Self to the Other. Elena Biserna in conversation with Brandon LaBelle”, in Brandon LaBelle (ed.), Overheard and Interrupted: Works by Brandon LaBelle, Dijon, Les presses du reel.

Brambilla, Chiara, 2015, “Il confine come borderscape”, Intrasformazione. Rivista di Storia delle Idee, 4:2, p. 5–9.

Bull, Michael, 2005, “Auditory”, in Caroline A. Jones (ed.), Sensorium. Embodied Experience, Technology, and Contemporary Art, Cambridge, MIT.

Cage, John, 2004, “The Future of Music: Credo”, in Silence: Lectures & Writings, London, Marion Boyars Publishers.

Connor, Steven, 1997, “The Modern Auditory I”, in Roy Porter (ed.), Rewriting the Self: Histories from the Renaissance to the Present, London/New York, Routledge.

dell’Agnese, Elena and Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary, 2015, “Borderscapes: From Border Landscapes to Border Aesthetics”, Geopolitics, 20:1–10.

Feld, Steven, 1994, “From Ethnomusicology to Echo-Muse-Ecology: Reading R. Murray Schafer in the Papua New Guinea Rainforest”, The Soundscape Newsletter, 8, https://www.acousticecology.org/writings/echomuseecology.html.

Jay, Martin, 1988, “Scopic Regimes of Modernity”, in Hal Foster (ed.), Vision and Visuality, Seattle, Bay Press.

Kirkegaard, Jacob, 2015, “Through the Wall”, in Jacob Kirkegaard: Earside Out, catalogue, Museet for Samtids Kunst, Roskilde, Narayana Press. http://fonik.dk/works/wall.html (last consulted in September 2016).

LaBelle, Brandon, 2012, “On Listening”, Kunstjournalen B-post, http://www.kunstjournalen.no/12_eng/brandon-labelle-on-listening (last consulted in September 2016).

Mannucci, Valerio, 2004, “Intervista a Justin Bennett”, Exibart, http://www.exibart.com/notizia.asp?IDNotizia=10502&IDCategoria=211 (last consulted in September 2016).

Mezzadra, Sandro and Brett Neilson, 2013, Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor, Durham/London, Duke University Press.

O’Callaghan, Casey, 2007, Sounds. A Philosophical Theory, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Parizot, Cédric, Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary et al., 2013, “Vers un anti-atlas des frontières”, http://www.antiatlas.net/vers-un-anti-atlas-des-frontieres/ (last consulted in September 2016).

Pisano, Leandro, 2017, Nuove geografie del suono. Spazi e territori nell’epoca postdigitale. Milan, Meltemi.

Popescu, Gabriel, 2012, Bordering and Ordering the Twenty-first Century: Understanding Borders, Plymouth, Rowman & Littlefield.

Rancière, Jacques, 1999, Disagreement: politics and philosophy, translated by Julie Rose, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press.

Schafer, Raymond Murray, 1977, The Tuning of the World, Toronto, McClelland and Steward.

Strüver, Anke, 2005, Stories of “Being Border”: The Dutch-German Borderscape in People’s Mind, Münster, LIT Verlag.

Ultra-red, “Mission Statement”, http://www.ultrared.org/mission.html (last consulted in September 2016).

Ultra-red, 2008, Ten Preliminary Thesis on Militant Sound Investigation, New York, Printed Matter.

Ultra-red, 2012, Five Protocols for Organized Listening, www.ultrared.org/uploads/2012-Five_Protocols.pdf (last consulted in September 2016).

Varèse, Edgard, 1940, “Organized Sound for the Sound Film”, The Commonweal, 13 December, 204–5.

Vila, Pablo, 2000, Crossing Borders, Reinforcing Borders. Social Categories, Metaphors, and Narrative Identities on the U.S.-Mexico Frontier, Austin, University of Texas Press.

Winkler, Justin, 2001, “Paesaggi sonori”, in Albert Mayr (ed.), Musica e suoni dell’ambiente, Bologna, Clueb.

Discography

Ultra-red, 2002, La Economia Nueva (Operation Gatekeeper), Splinter Series 3" CD, Fat Cat Records.

WR, 2005, Border Sounds, Public Record No 2.02.005, free download: http://www.ultrared.org/publicrecord/archive/2-02/2-02-005/2-02-005.html (last consultation September 2016). suite...

Notes

14 1. Elena dell’Agnese and Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary reconstruct the various uses of the term by tracking down its first appearance in the title of a performance by artists Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Roberto Sifuentes, Borderscape 2000: Kitsch, Violence, 25 and Shamanism at the End of the Century (1999) (dell’Agnese and Amilhat Szary, 2015). 2. For a critical approach to field recording informed by cultural and postcolonial studies, see Pisano 2017.

3. In this text, I limit myself to analysing two works by artists Justin Bennett and Jacob Kirkegaard, but many more field recording projects focus on borders. Among others, Border Zone Recordings – a project by artist James Webb recording official and unofficial borders between countries – and Belju Soundbridge, started by Gilles Aubry, Stéphane Montavon and Carl.Y in 2009 to explore the French-Swiss border and incorporating various forms of listening, recording and sound performance (the results have been published in an online format: http://belju.universinternational.org/, last consulted in September 2016).

4. For more on the border’s polysemy (the fact that the border signifies different things for different social groups), see Balibar 1994.

5. In particular, I am thinking of the series entitled Surveying the Future, which was started in 2001 and focused on migrants’ conditions, migratory policies and racism in Europe in countries like Germany, Serbia and the United Kingdom: http://www.ultrared.org/pso7.html (last consulted in September 2016).

6. In another album, Play Kanak Attak (2002), the group directly tackles the dual regime that characterises freedom of movement in the global society: “The free movement of people must be recognized as an aspect of everyday life. Such freedom must be recognized for all people, from sex workers, to agricultural workers, families and lovers seeking reunion, Roma people, political refugees, and not just the sole right of privileged workers of the neoliberal order, like NGO workers, technical elites and cosmopolitan electronic musicians”, http://www.ultrared.org/pso7b.html (last consulted in September 2016).

7. He writes: “As the term ‘music’ seems gradually to have shrunk to mean much less than it should, I prefer to use the expression ‘organized sound,’ and avoid the monotonous question: ‘But is it music?’ ‘Organized sound’ seems better to take in the dual aspect of music as art-science, with all the recent laboratory discoveries which permit us to hope for the unconditional liberation of music, as well as covering, without dispute, my own music in progress and its requirements” (Varèse, 1940).

8. The Freedom of Speech Itself (2012), for example, is an audio documentary that uses witness testimony by barristers, phonetics experts, asylum-seekers and officers from the British Home Office to examine the use of voice analysis when determining the origins and authenticity of the accents of asylum seekers in the United Kingdom. The documentary ended up being submitted as evidence to a British tribunal for asylum-seekers, where the artist was also called to testify. Aural Contract is a sound archive that was launched in 2010 to collect a heterogeneous ensemble of documents on the role of the voice in courtrooms: interviews with voice analysis experts or refugees who are subject to phonetic analysis, legal discourse (including the trials of Saddam Hussein and Slobodan Milošević), film extracts and text excerpts, recordings made by the British Police, instructions or demonstrations of voice analysis technologies etc.

9. In Israel, for example, the Druze are Arab-language citizens, serve in the army and participate in political life but are considered a distinct ethnic community and are often subject to the same discrimination faced by other non-Jewish citizens.

10. For more on the “internalisation of borders” – the individuals’ sense of belonging to a nation state and their identification with the figure of a “national citizen” – see Balibar 1994.

11. On the relational nature of sound, see, among others, LaBelle 2012.

12. This deconstruction of the object/subject dichotomy matches up with the anti-oculocentric currents of philosophical and social thinking in the 20th century – from the deconstruction of the subject in the psychoanalysis of Jacques Lacan to Michel Foucault’s analysis of panoptic apparatuses – analysed by Martin Jay (1988): “Cartesian perspectivalism has, in fact, been the target of a widespread philosophical critique, which has denounced its privileging of an ahistorical, disinterested, disembodied subject entirely outside of the world it claims to know only from afar” (1988, 10).

13. For an analysis of the history of this notion of the border and of the development of its linear representation, see Popescu (2012), among others.

14. Steven Connor (1997, 207) uses the image of the membrane to illustrate his auditory conception of the subject: “The self defined in terms of hearing rather than sight is a self imaged not as a point, but as a membrane; not as a picture, but as a channel through which voices, noises and musics travel.”

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/02-Biserna-soundborderscapes-lending-a-critical-ear-to-the-border.pdf