antiAtlas Journal #2 - 2017

The political arithmetic of borders: towards an enlightened form of criticism

Thomas Cantens

Thomas Cantens is the head of the Research Unit at the World Customs Organization. Before joining the WCO in 2010, he served in French Customs, and as a Technical advisor of the Directors General of the Maliand and Cameroonian Customs for 6 years. Thomas has a degree in engineering and a PhD in Social Anthropology and Ethnology from Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales. He is a associated lecturer at the Auvergne University School of Economics (France).

Keywords: borders, numbers, data, ranking, modelling

To quote thispaper: Cantens, Thomas, "The political arithmetic of borders: towards an enlightened form of criticism", published on December 10, 2017, antiAtlas Journal 02, 2017, online, URL : https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/02-the-political-arithmetic-of-borders-towards-an-enlightened-form-of-criticism, accessed on date.

Introduction

1In his war comedy, Acharnians, Aristophanes reminds us that the real meaning of drawing a border stands in contrast to the message conveyed by the current security discourses on our European borders. The play is set in Athens in 426 BC, at a time when the city is engaged in predatory relationships with its neighbours. Pericles is receiving criticism both for his indifference towards the enemy lootings in Attica and for the greed that leads him to undertake expeditions in far-off lands. In public, Dicaeopolis, who is Aristophanes’s pacifist hero, challenges the general attitude of belligerence. Unable to sway public opinion in his favour, however, he decides to secure a truce – man alone – with the enemy cities. An envoy brings him a variety of truces in the form of wine. Dicaeopolis tastes them and chooses the one that is the least bitter, the softest and lasts the longest: 30 years on land and on sea. However, securing a truce all on one’s own is not, one can well imagine, something that is easy to put into effect. Back at home, in front of his house, Dicaeopolis makes a very simple gesture that will paradoxically isolate him from his own hawkish people and bring him closer to the others: He draws a border. It marks the edge of a market where he establishes free trade, and where everyone is welcome to do business with him, including those from places considered to be enemy cities, on the condition that they do not trade with any Athenians who support the war. Thus, Dicaeopolis draws a border against the war. The pacifist hero ultimately wins over people’s hearts when they bear witness to his prosperity and the needless suffering of warrior “heroes”. Dicaeopolis’s pacifist gesture reminds us that a border is always related to time and relationships with others. At a time when public discourses in the West are convulsing over the mention of borders, Dicaeopolis’s pacifist gesture reminds us that a border is always related to time and relationships with others. It enables any “one” party to define themselves not necessarily by being different but on the basis of a practical relationship with “another”, an endlessly repeated choice between trading blows and trading goods.

next....

2The border is not just a wall that is built, however. The governance of trade is probably one of the most developed forms of international governance. It is the product of institutions and of the bureaucracies that manage them, whether through bilateral agreements or customs unions, international conventions about the coding of physical objects, international trade tribunals, exchanges, the International Chamber of Commerce or, since the 1950s, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (regarding customs tariffs and trade), which was transformed into the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1994 and has its own “tribunal” to settle disputes. International and transnational organisations are the main players and form the arenas of this governance. The WTO, the World Customs Organization (WCO), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the World Bank, the World Economic Forum (WEF) and the Organization for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD) are all interested in borders, in what it costs to cross them and in those who are the stakeholders in this “border–barrier”: states, their infrastructures, rules and bureaucracies, along with those of parastatal authorities that are in charge of harbour and airport platforms and those of transport and logistics companies. How do we make these borders appear in order to “manage” them, besides the sporadic physical manifestations of legal purposes in the form of walls, wire meshes, fences and canisters on a road or in the middle of a city straddling two states? Everywhere, border surveillance and control happens in this border space – economic resources considered with regard to their value and the prospects they offer for trade. How do we make these borders appear in order to “manage” them, besides the sporadic physical manifestations of legal purposes in the form of walls, wire meshes, fences and canisters on a road or in the middle of a city straddling two states? How do we go about transforming these borders into technical objects that have continuity in time and space and have policy effects in terms of the organisation of trade between societies? next....

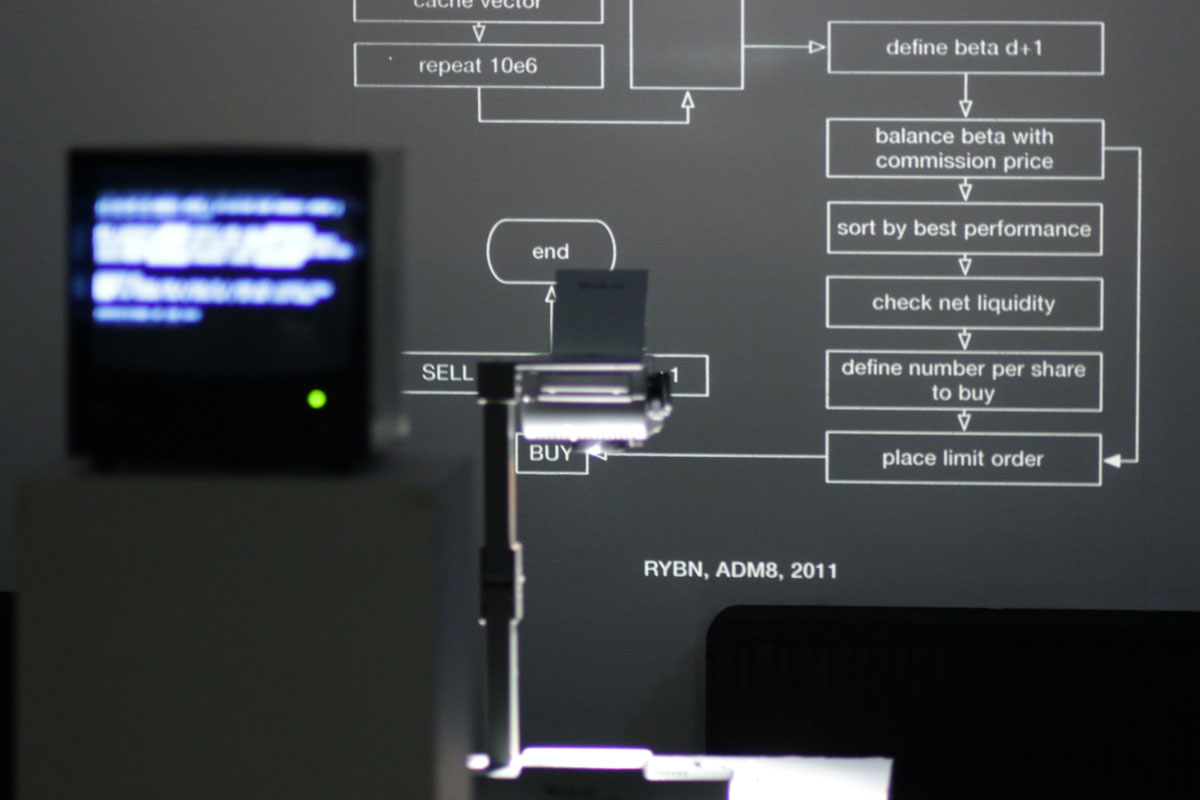

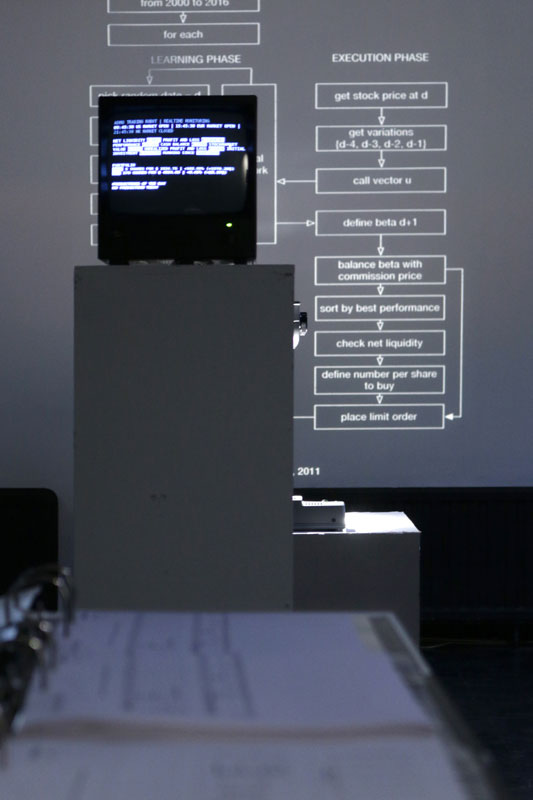

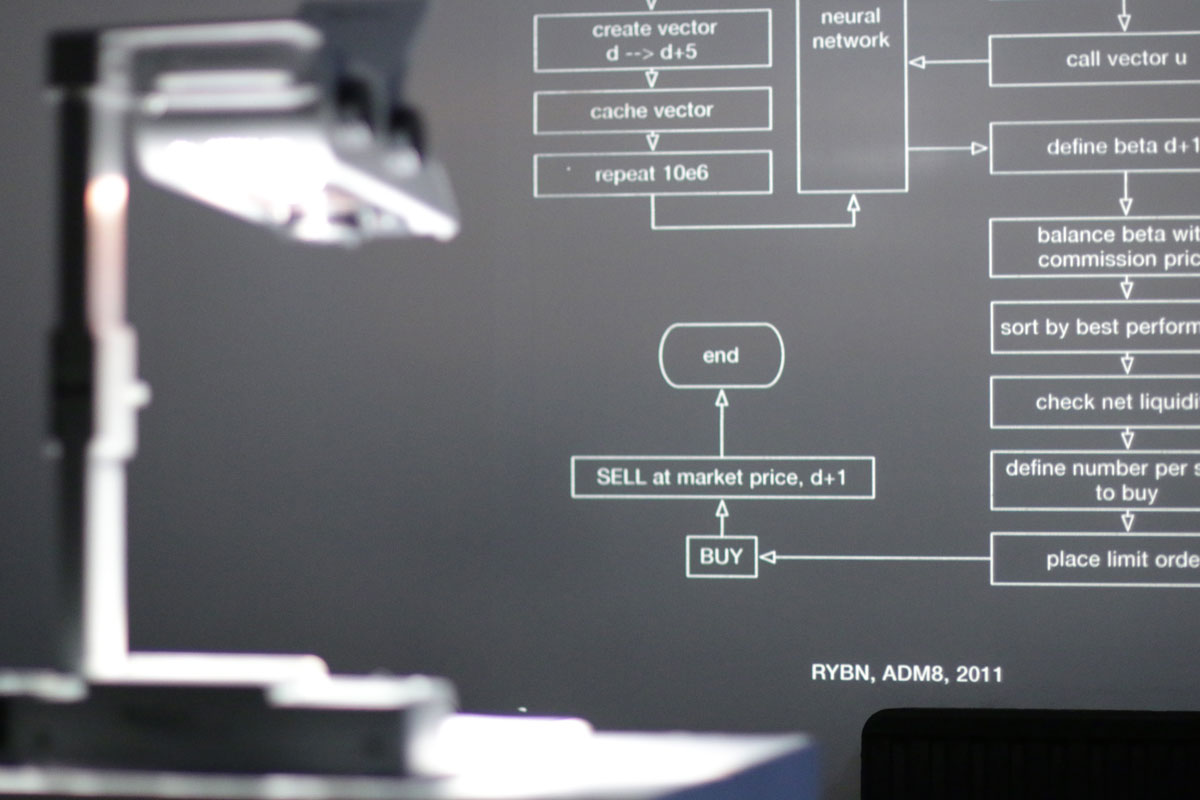

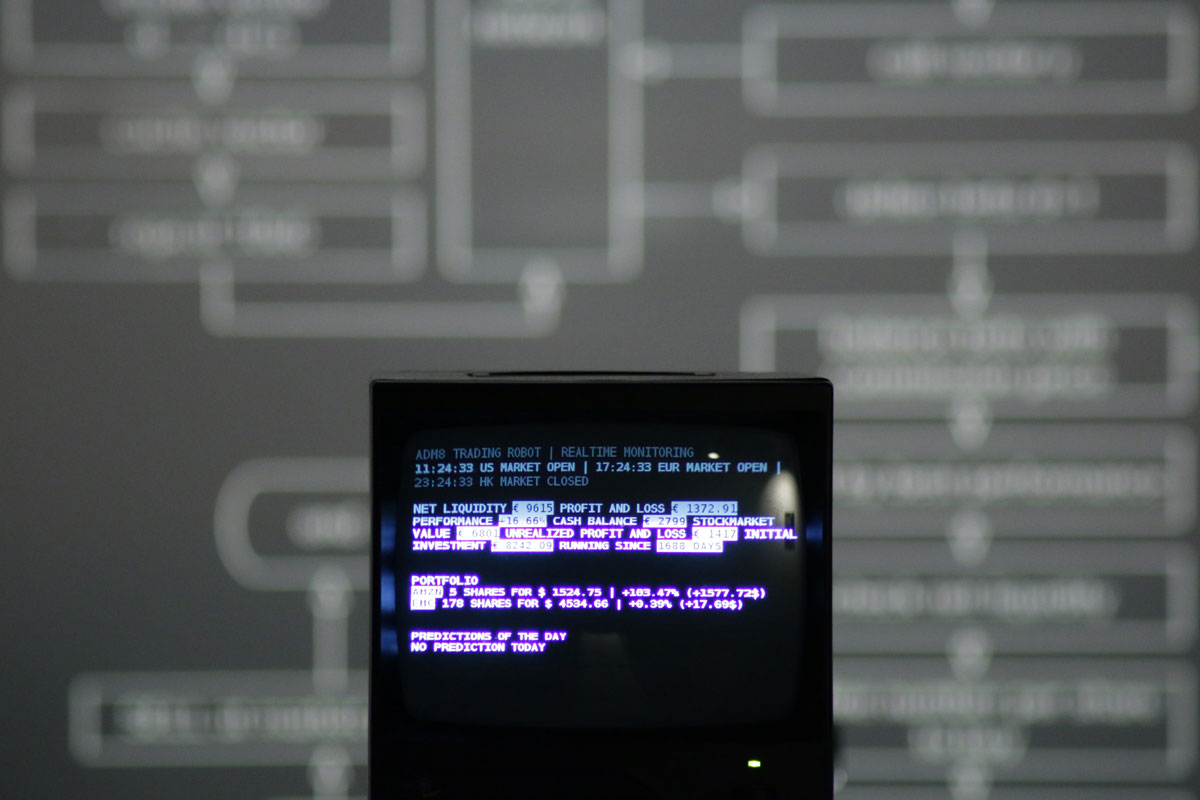

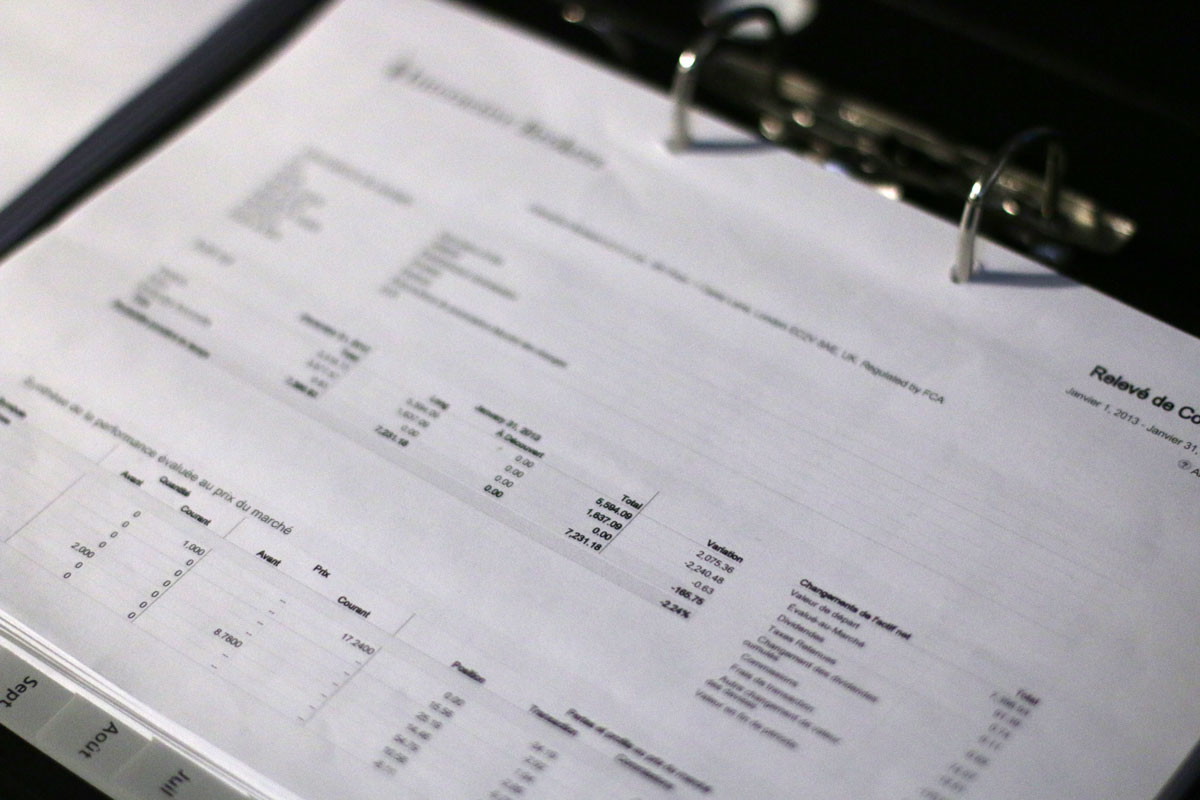

All the images used in this paper: ADM8, installation, 2011 - 2015, RYBN collective Photographs © Myriam Boyer

3The interest in governing borders has zeroed in on data and primarily on how states go about collecting them. The phenomenon of datafication is real; the term covers both the increase in the amount of data that states request as a precondition to crossing borders and the expansion of states’ technical and legal means to work with these data. However, this trend forms part of a quest for efficiency that is a constant in the State’s historical and bureaucratic development in the West. By itself, it does not signal a shift in the nature of governance. By contrast, the mathematisation of borders seems to be a more thought-provoking notion. This is the phenomenon as part of which quantitative and qualitative data are linked together by means of calculations in order to produce quantity-based results. We are familiar with the practice of calculation, but to date, the way in which it shapes our thoughts has received little attention (Hansen 2015). The spreading of calculation-based thinking to all fields of border management has changed our way of thinking about borders by placing them in a relationship of global commensurability, measurement and comparison of societies on an international scale. The idea developed in this article is that this mathematicisation becomes a language, the language of calculation has changed the conditions for criticising public policies, and in this context criticism has to be expressed in this language of calculation if it wants to be effective. The spreading of calculation-based thinking to all fields of border management has changed our way of thinking about borders by placing them in a relationship of global commensurability, measurement and comparison of societies on an international scale. The first section describes datafication from the perspective of goods and shows why this quantitative representation of trade is nothing new. Its novelty is described in the second section: Calculation becomes a common language for those who take part in governing the border. The third section looks at what is involved in calculation practices and how they produce a political representation of boundaries. The fourth section examines how effective common criticisms levelled at this governance by numbers are when they are applied to border management. And the fifth section defends the idea that it is not so much the criticism’s substance but the form it takes that is erroneous, and in order to be heard and be effective, it might be necessary for critics of this governance to arm themselves with figures. next....

I. The "datafication" of borders

4In essence, we think of and control borders through figures and data, and it has become commonplace to refer to this as datafication (Amoore and De Goede 2005, Parizot et al. 2014, Bigo 2016, Broeders and Dijstelbloem 2016). The phenomenon is as old and rooted in the management of international trade as the extent to which it is criticised when applied to people. Goods have been datafied for at least the past 30 years: their specifications, value, origin, source, and the stopovers of the ships, planes and trucks that transport them are transformed into datasets in port, airport and customs information systems. Around 30 data points are required to signal to a state that a good is about to cross its border, and at least 50 data points are used to describe the good once it has passed through the border but before customs authorities clear it for release. In addition, there are data obtained from the supporting documents, certificates, licences and so forth, all of which are attached to the customs declaration, part of which is digitised. The bulk of the efforts by international organisations like the WCO and the WTO involves harmonising, communitising and simplifying the data and the procedures related to borders. Around 30 data points are required to signal to a state that a good is about to cross its border. Since al-Qaida attacked the United States in 2001, the usefulness of data has evolved. It is important to be equipped in order to prevent a rare event – a “terrorist” act – from occurring, and in this regard having control over borders is essential. The logic of customs control programmes like the Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism, the U.S. Bureau of Customs and Border Protection’s Container Security Initiative and Europe’s 24-hour rule rely on data being available before a border is even crossed: The more state services ask for data about the goods and those who transport them at the time the goods are loaded abroad, the better they can analyse the specific risk that each piece of cargo poses and reduce the need for physical controls at the border. This logic has extended the customs and police border beyond the geographic, national or Community border. There are several factors behind the expansion that the field of the datafication of goods has undergone: i. a need to respect the rules of law (more data means greater accuracy when calculating duties and customs taxes), ii. a willingness to facilitate the physical crossing of the border, iii. a growing need for the border to play a vital role in fighting insecurity and terrorism in particular, which makes international trade facilitation as much of an economic imperative as a risk (Cantens 2015a), iv. a policy of surveillance based on collecting all kinds of data with an eye towards potentially using them at a later stage: big data surveillance (Andrejevic and Gates 2014), v. a wish to reduce the costs of state control by using information and communication technologies (Clavell 2016). next....

5Taken on its own, representing the world of trade in terms of numbers is neither new nor problematic. During the period stretching from the middle of the 17th century to the middle of the 18th century, a science of trade was created in Europe, which consisted of trade manuals written by intellectual traders. The French example par excellence is The Perfect Merchant (Le Parfait Négociant) by Jacques Savary. First published in 1675, Savary’s work found immediate success, which continued over the following centuries: By 1800, it had been reissued 32 times, passages from the work were included in U.S. accounting manuals until 1900 (Parker 1966), and the Geneva-based publisher Librairie Droz reissued it again in 2011. In around 1,000 pages, Savary chronicles French manufacturing, the manufacturers’ tricks of the trade and the brand names of the fabrics destined for export. Savary weighs, measures and calculates the rule of three for units of length, volume and money from one city or one country to the next. He does not limit himself to French fabrics but lists what is extracted from the soil or produced elsewhere. He examines the laws of a country, reports on France’s legal regulations, warns of fraud in neighbouring countries, talks about the lives of Dutch and English traders in distant continents and encourages mistrust of – or, on the contrary, leniency towards – “new” peoples. The book educates, warns, declares, calculates and shares the perils of the adventure of trade; it creates a world, a trade space of the commensurable, where abundance is a sign of goodness. The book follows the movements of a world where magnitudes, quantities, places, countries, routes, laws and calculations, economic principles and analyses, private counsel and political injunctions come together in one place. Savary writes in the preface that this essay of essays on traders who refuse to be quoted reveals their liveliness, their calculation-based way of thinking and a talent for observation that impressed even Montesquieu. During the period stretching from the middle of the 17th century to the middle of the 18th century, a science of trade was created in Europe. During this time, “the spirit of calculation” was used to describe this way of thinking about the world and social relations. In 1753, Véron de Forbonnais wrote in the preface to the French translation of a Spanish trade manual: “For more than a century, the spirit of calculation has done more to contribute to the goodness of the Earth than philosophy lessons in all previous centuries” (p. iii). This science of trade was not based on any model; it only sought to intensify that which existed already. It is science without the Market, a quasi-cartographic review of the trading area at the same time as this area was being constructed by this knowledge. In the middle of the 17th century, while the Europeans opened up to the world with which they traded, this spirit of calculation was enthusiastic about the material world, but that does not necessarily imply that the knowledge that is produced can be used to govern it. The traders roamed a wholly commensurable world with nothing more than the rule of three (Cantens 2015b). The emergence of other calculation practices would prove to be more problematic. next....

II. Mathematising and governing the borders

6These other practices underpin the contemporary governance of international trade, which is a governance that was originally effected not through legislation but by injunction, example and best practices by means of quantity in the form of measures, indicators, scores and rankings. As one of the stakeholders in this governance, the World Bank produces an annual report, Doing Business, which ranks countries according to the ease of doing business there. Borders are represented by a macro-indicator, Trading Across Borders, which is the result of calculations carried out on the indicators of time and the cost of crossing the border. On the basis of these same principles, the World Bank produces the Logistics Performance Index, the OECD issues Trade Facilitation Indicators, and the World Economic Forum (WEF), a transnational organisation known for the Davos Conference, produces the Enabling Trade Index. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have also developed tools to take into account the state of governance by country and region and thereby assist governments’ tax and customs administrations. These data, which are measures, are turned into indicators with meaningful titles. What do these instruments do? They do not offer, a priori, economic, econometric or statistic modelling. Their only aim is descriptive, in the manner of Savary. The raw data are collected from private players (economic actors, national consulting firms) or public players (customs administrations, in particular). These data relate to transit times, the time it takes to complete formalities, the number of documents required, expenses paid to different public and private players at the border, bribes, the degree of confidence in institutions etc. These data, which are measures, are turned into indicators with meaningful titles. The indicators are subsequently subject to simple mathematical calculations that will be covered in the following section and whose results are scores by country and are used to produce international rankings. On the basis of our observations and interviews with economic operators and officials, there is some confusion between measure and indicator that is linked to a stinging, albeit ineffective, criticism of these instruments, namely that they are “subjective”. This confusion is dangerous because it weakens the strictly linguistic dimension of what is happening. In fact, when the World Bank measures the number of documents required to import merchandise, this number is a measure and is objective. To say that a certain percentage of importers do not have faith in the justice system is also an objective measure – of perception. By contrast, the measure is based on data provided by private players, who are not neutral with regard to the State, because they are subject to its control. It is also possible to counter that the importers who were interviewed are not representative of the international business sector, or that the measure hinges on a universal scenario being offered to importers and exporters in order to guarantee the answers’ comparability. Nevertheless, the measure is objective in practice. International organisations make their data and methodologies publicly available. Despite this transparency, the same objectivity does not hold true when a measure becomes an indicator’s quantity. Despite this transparency, the same objectivity does not hold true when a measure becomes an indicator’s quantity. The indicator is symbolic: It signifies something different than what it is. The number of documents is a quantity, and assigning it the role of representing the degree to which it facilitates a country’s business is a subjective and political act. After all, the “document” that is required and produced by the State could also add some value to the item that is traded, as a guarantee of quality or integrity. The indicator says somewhat more than merely the figure it conveys – it says something about “a” problem. next....

7This calculation-based thinking, along with the law, is what produces the border. These international rankings benefit from two factors that amplify their influence: International and transnational organisations’ ability to publish, and the ongoing criticism of these annual reports, in particular of Doing Business, which also contributes to raising their profile. On the ground, it is easy to notice as much: Political authorities, who wish to see their country climb in the rankings, push for changes in customs regulations. The indicators are mobilised by political authorities, legal experts, other experts, national and international officials and economists, who are the key players developing and implementing public trade policies. Doing Business has had a considerable impact on political and legal reforms (Michaels 2009), in particular in so-called developing countries. On the ground, it is easy to notice as much: Political authorities, who wish to see their country climb in the rankings, push for changes in customs regulations. This language of indicators not only makes sense in trade between different actors in public life but also influences economic science when the latter is harnessed to “demonstrate” the relevance of a political decision. In this regard, indicators are used in two types of mathematical analysis. The first analyses are econometric in nature; they test the validity of policy assumptions by using empirical modelling and data. The problem is that empirical data are not always available, and thus, the indicators are used as proxies. For example, while it is simple to measure the online presence of a website that contains information about customs regulations, it is very difficult to quantify “the quality of the regulation” in an empirical way. For this reason, one of the World Bank’s governance indicators is used as a proxy for this variable. The indicator is used as a measurable variable that replaces another, non-measurable variable that is similar in kind. The second mathematical process that uses indicators is more predictive. By using economic modelling, usually the gravity model for trade, it seeks to calculate what happens when the indicators improve. This is the case of the WEF (2014a), which calculates global gains when countries that are lagging the most in their ranking see their scores improve. The OECD’s Moïse and Sorescu (2015) use a similar method, which is an integration of the OECD’s Trade Facilitation Indicators in a gravity model, to estimate the gains produced by so-called developing countries implementing the WTO’s trade facilitation agreement. One cannot help but see something endogenous about this use of the indicators, in various ways: international organisations’ construction of indicators on the basis of other organisations’ indicators ; international organisations’ production of indicators, followed by their inclusion in modelling with the purpose of mathematically “demonstrating” the validity of the standards that these very same organisations design and promote at a policy level. next....

8These instruments that calculate, rank and order in all senses of the word are not ranking states – they sketch a world of borders that have to be crossed; they create a topology that shakes up geography, where distance is measured no longer in kilometres but in days, minutes, American dollars, number of documents, formalities and the satisfied economic agents’ percentages. In the WEF’s 2014 report, the global gain in GDP is calculated in the case that each country reduces its “distance” – in the ranking – from the best by half. The principle behind this governance is linguistic in nature. It is a set of practical methods for calculation and indicators that spread out, affect decisions and fit with each other. It involves a lingua franca, a koiné language that is developed with a very specific goal in mind and allows communication among those who carry out the actions for states: legal experts, economists, other experts and national and international officials. In this regard, datafication is only a condition of governance; it focuses attention but does not impose a way of thinking, unlike mathematisation and its strength as a language. suite....

III. A few principles of the language of calculation as applied to borders

9The major problem with calculation as a language is not its disproportionate use but rather how it makes us think about borders. In particular, two principles specific to calculation mould governance to such an extent that they became governance itself: comparison and aggregation. Commensurability is common to the governing of the flow of things and individuals. It is certainly not a given, but it is a political production, and we have to acknowledge its endurance since the 17th century in the way we think about societies and the trade between them. Digits have not only a cardinal but also an “ordinal” virtue. Mathematics draws heavily on order and hierarchy (Régnier 1968), and ranking is one of the main operations of contemporary governance (Hansen 2015). It is important to remember that, sooner or later, the use of numbers leads to ordering. It is not possible to measure without comparing, despite the desire of administration officials who want to evaluate their services with the help of international instruments but are reluctant to make comparisons. Comparison is inevitable, but its effect can be minimised. The second (mode of) governance that calculation makes possible is aggregation. Figures are aggregated, and consequently, different problems are aggregated into a single representation. In the end, all the previously mentioned instruments of governance yield a score for the country. This score is the result of calculations made according to indicators that have different units and relate to time (crossing times), money (costs), percentages (for example, the number of economic agents who were “obliged” to pay a bribe during a formality) and objects (number of documents). This diversity of units poses a computational challenge that also has a policy component. To understand this challenge, let us take the example of the World Economic Forum’s Enabling Trade Index (ETI). The ETI produces a score by country on the basis of 56 indicators. Each indicator relates to an issue or a problem (the transparency of procedures, the private sector’s participation in the drafting of regulations, the number of days it takes to pass through the border, the cost of importing a container, the number of documents…). Each indicator is integrated into a whole of assessment “principles” (market access, the role of border administrations, transparency…). Inside every whole, the indicators are subjected to weighted averages that yield a quantity for each group of indicators. These quantities per group are, in turn, aggregated to a single score per country, using another weighted average. The principle seems to be a simple one: A priori, there is a progressive aggregation of the amounts in order to reach a unique quantity, the “score”, followed by a ranking. Understood as such, each score identifies the country – and only the country – before its ranking. Thus, it would be possible to follow the evolution of a country’s score over time, which is what economists or governments do to measure or evaluate reforms. The reality of the calculation is a bit more complex. The diversity of “problems” – and thus, of the indicators – means they all have different units. The solution to making them “aggregatable” therefore lies in recalculating the indicators in such a way that all of them are quantifiable in numbers taken from an identical segment, for the ETI on a scale from 1 to 7. next....

10Another solution that could be adopted is one that economists sometimes use: transforming everything into money or geographic distance – the cost of a document and of obtaining it, the cost of waiting and the cost of bribes. Nonetheless, that would create a major problem: It would be impossible to estimate the cost of a pure representation, such as satisfaction, for example, or the participation of the trade union of importers in negotiations on public policy. For this reason, this particular solution was only viable on condition that only that which is material be measured, and not that which is represented by users or citizens. The decision to turn all indicators into a number from 1 to 7 creates problems. How does one turn days or dollars into a unitless number? There are two ways. The first way is to compare the received information (3 days to clear a container through customs, 60% of businesses consider administrative work to be a major obstacle…) with a fixed threshold: the value that has to be reached in order to be “good” (1 day, 90% etc.). How are the thresholds fixed? They come from what experts have determined to be “best practices”. In other words, they are purely subjective. This decision was made for certain instruments – those that are supposed to support the governments in carrying out their reforms. Just because they are subjective does not mean these instruments are bad – if I said a file has to be dealt with within one day in order to be “good”, how can anyone counter such an assertion? – but it is easy to guess what the criticism of these instruments would be: the criticism of proclaiming a governance model by imposing quantitative thresholds that are supposed to take into account “a good performance” for a typical administration. The second way seeks to avoid this criticism but is not altogether successful in doing so. This way, adopted by the ETI, is to recalculate an indicator for a country by identifying its position in relation to the “strongest” and the “weakest” countries. The formula below illustrates this approach and is taken from the ETI 2014 (World Economic Forum 2014b): The standard formula for converting each value to a 1-7 scale is: 6 x ((country value - sample minimum value)/ (sample maximum value - sample minimum value)) + 1 In other words, the comparison produces an ecosystem of borders in the sense that it is not borders or the countries themselves that are compared with each other, but rather the relationships between them. Thus, even though the comparison is only, on the face of it, the result of calculations, the way in which these scores are calculated is already based on a principle of comparison because of the ranking of the national scores. In other words, the comparison produces an ecosystem of borders in the sense that it is not borders or the countries themselves that are compared with each other, but rather the relationships between them: Your “progress” is tied to that of the others. Aggregation is handy, but it leads to confusion. One could view this confusion as something that has a salutary effect because it dismisses both the public and private players who “slow down” the flow of goods at the border. Nevertheless, aggregation is also the new language’s ability to serve as a common form of communication in the governance of trade: It is a form of organisation “from the top down”, in other words, according to its objectives – to point out what costs and what subtracts value from the goods. In this respect, it is political and debatable. No indicator takes into account the added value of the State, which certifies and attests to the value of the goods, the legality of the operations and thus the trader’s observance of transparent competition rules. The principle of aggregation is the shift from the real to the ideal, a representation of the real through data that have units to a representation of the real without units. This distinction is nothing new; it formed the basis for the Platonic city and power. Following the division of labour, a founding principle of the Platonic city along with the necessary lie of the myth, Plato identified two uses for calculation according to whether or not units are used. The guardians practise a form of arithmetic without units while the traders and the craftsmen are the people of things and count in units. Since Plato, leading has meant calculating without units – without the material world.

next....

IV. Criticising governance at the borders

11Surveillance and border control policies have raised numerous criticisms of datafication, the widespread use of technology and the prevalence of calculation-based and utilitarian thinking. Many of these criticisms are ineffective. The first series of criticisms focuses on the fact that numbers are used at all. According to this line of thinking, numbers are deceptive and falsely objective, and governance by numbers is the epitome of “neoliberal” governance, in particular since the 1970s and the introduction of businesses’ management techniques in the public sector (New Public Management). The use of figures has the benefit of being methodologically – and thus, ideologically – transparent. There is nothing reasonable about criticising the use of numbers by alleging a duplicitousness that would make the general public believe in a perfect analogy between reality and its representation in figures: No one is fooled. Figures are not the complete picture of reality; they are the result of political choices, and everybody is aware of this. Rankings are part of Anglo-Saxon advocacy. If I have demonstrated above that the choice of indicators or calculation methods themselves serves a specific policy objective, it is because the methods of calculating rankings are clearly described by the organisations that produce them. The use of figures has the benefit of being methodologically – and thus, ideologically – transparent. The use of figures must not be correlated with the political ideologies that mobilise them. The connection between governance by numbers and so-called neoliberal policies is a historical and methodological mistake. The most prominent affiliations of governance by numbers include the Soviet Gosplan and the cybernetics of Wiener (Supiot 2015), who was rather subversive at the outset because he sought man’s development through his freedom to act based on information received and in opposition to his subservience to an authority. A second series of criticisms condemns any change in the nature of state control: the shift from control based on the eradication of the roots of trouble to control based on the prediction of trouble (Cukier and Mayer-Schoenberger 2012) and, as a result, the stigmatisation of individuals and a halt to the development of control policies by state experts. The significant amount of data that the state collects enables them to shift from research into causes to a prediction of effects by establishing links of correlation, simultaneity and succession. Prediction means that identities are defined by control (Davidshofer et al. 2016) and also distinguishes between various risk groups (Leurs and Shepherd 2017). Of course, the predictive dimension is not exempt from criticism, as the calculations ascribe suspicion of illegal behaviour to individuals who have done nothing wrong, and because this evaluation has an impact on their freedom of movement (the same is true for goods, albeit with less severe consequences). However, this question of the stigmatisation of individuals can very well be tackled not as a mistake in the nature of the system of control but as a vagueness that can be improved on. In response to this question, as is the case with false positives or the exclusion of certain groups from the analysis field because they are not “connected” to the systems of data collection (Redden 2015), the responses from the state services will likely be the same: Collecting more data will reduce the risk of making a mistake. I am not sure I prefer a policy based on causality while it is scouring for causes to crimes so that they can be eradicated, according to the terminology of Lyon (2016: 266). Social determinism has created many illusions, in various domains, for example the policies of official development assistance that have been implemented since the 1950s with the aid of econometrics (Jacquet 2011). I am not sure that I prefer a determinist position, which seeks to demonstrate links of causality on the basis of testing hypotheses, over the anti-causality positions that are more stochastic and, at the end of the day, seem to be liberal enough in the purest sense of the word. Finally, states use the data that they collect to develop their own border policies (Broeders and Dijstelbloem 2016). This makes having a public debate problematic because states have a monopoly on the data they collect, in particular, data that are pertinent to border surveillance. While this assertion is plausible, one must acknowledge that it also has three shortcomings. The first is that the authors do not provide any evidence to substantiate their claim, for example, by showing in what way the data collected on the flow of individuals have played a crucial role in developing a particular migration policy. There are no specific examples with respect to the control of goods, either. In fact, some examples show quite the opposite to be true – namely, that there is no state strategy to make analytical use of the data beyond managing human resources. The second shortcoming of the assertion is of a logical nature: The decision to monitor and control certain objects is made in order to collect data on them; no data are collected on objects that there is no desire to monitor and on which one would realise after that fact that it ought to be done. Analysing data about objects means they have already been turned into surveillance targets; the rest is technical detail. Lastly, the reality makes it plain to see: Migration policies appear to be rooted in an appeal to people’s emotions – and not necessarily the best among them – rather than a fact-based analysis. In the same way, the attacks of 2001 on the United States radically changed the relationship with certain tools that are used to control goods, such as scanners: Prior to 2001, container scanners had been viewed as unprofitable, but overnight they became indispensable tools for a policy to control U.S. ports (Ireland 2009, Cantens 2015a). next....

12A third criticism, that of the Orwellian State, makes up the disquieting sub-heading to a very real observation: More and more individual data points are being collected, states’ storage capacities are growing, the data are centralised, calculation and decision-making centres are linked to each other, decisions are automated, police officers who carry out the controls are free from liability, and programmers and mathematicians, whose expertise remains opaque to the general public, supersede the police. These observations are true, but what makes them criticisms? What about the shift itself (from the craft to the mass production of control) creates a political problem? Might we expect the states to adopt a different trajectory? The surveillance and control of the population are part of the State’s genetic make-up. It would be very surprising if states dispensed with any particular means to carry out surveillance, even if a majority of the population wanted it to do so. There has been a flood of criticism against state surveillance and control technologies, in particular with respect to migration. This is probably linked to the proliferation of surveillance systems and their expansion outside places of pure coercion such as prisons, namely in the workplace or government. These contemporary changes make it difficult to propose unified theories of surveillance. Should we therefore abandon our criticism? We should keep in mind the goal of reflecting on governance: talking about governance probably always means criticising the current governance to some extent. It is not about creating theoretical frameworks “to put into practice” but about making the theory of power the practical precondition for a critical review of this governance. Foucault and Deleuze produced concepts but also did something with them – they were fighters (Dosse 2009) and navigated between practice and theory. This navigation is necessary because the preconditions for criticism are necessarily historical in nature, in Deleuze’s sense: “A theory is exactly like a box of tools… It must be useful. It must function. And not for itself. If no one uses it, beginning with the theoretician himself (who then ceases to be a theoretician), then the theory is worthless or the moment is inappropriate.” (Foucault 1977: 208) It has become clear to everyone that the only thing capable of moving with ease is that which has a form (of life, of accounting) that is recognised as conforming to the expected models of certain rich states whose borders are intensely sought after by migration and trade. And yet, these historical preconditions for criticism have undergone a change. The Western State is no longer required to be less authoritarian, which is something that was possible in the 1970s and 1980s, when Foucault’s and Deleuze’s theories of surveillance first appeared. The contemporary issue of surveillance, in particular of borders, is framed by a context in which the perception of insecurity and the demand for greater protection by the State – at least, in Western states – are real. Furthermore, knowledge and the language of calculation are placed at the core of public policies such that power, by virtue of appearing rational and transparent, is viewed as acceptable and no longer paternalist, moralist or authoritarian. By contrast, the algorithms that are used to calculate risk remain shrouded in secrecy, although their principle of existence is no secret. The acceptability of devising policies by using calculations has modified this principle’s conditions for criticism. The problem of most contemporary criticisms of border management policies is precisely whether or not the historical conditions for criticising governance have changed: the fact that certain ideas or principles are no longer problematic. It has become clear to everyone that the only thing capable of moving with ease is that which has a form (of life, of accounting) that is recognised as conforming to the expected models of certain rich states whose borders are intensely sought after by migration and trade. There can be a basis for criticising this, but the public players have already taken it upon themselves to do so; with regard to criticism, there is nothing left to reconstruct or reveal. next...

V. How to create the disagreement specific to politics?

13Where does one find the disagreement that politics requires (Rancière 1995) in a public space where deciding means calculating? Criticising contemporary calculation-based governance is ultimately based on the impression that state action no longer has any limits, because there is no limit to the data that can be collected, and the storage and calculation capacities are boundless. Faced with this impression of limitlessness, two limiting approaches are possible: disobey, or make law. However, contemporary state discourse is no longer legalistic; the law is now but a consequence. Over time, imposing legal restrictions on the collection and use of data can resolve issues such as the protection of privacy and hold back the surveillance of individuals. The law is a solution that appears to be “reasonable” (Broeders et al. 2017). However, contemporary state discourse is no longer legalistic; the law is now but a consequence. States reach an agreement with the law in order to create a “state of exception” without violating the rule of law, but without fully submitting to it, either. We also see how the law has been shaped according to international rankings. Whenever necessary, the law, in compliance with the relationships between legal entities, formalises that mathematisation adheres to the relationships between objects. This adherence is specific to the governance of societies, which have less and less appetite for an explicit form of authority (Borot 2002). The law is quietly changed over a long period of time and becomes a constraint we do not even think about anymore. Mathematical governance pushes us to adjust our rules permanently, following the feedback principle and the fact that we are essentially information-processing machines. This principle finds expression in the efforts required of administrations to adapt to new forms of international business and to the development of certain countries’ bureaucracies. While there are probably laws to protect privacy, as well as others that guarantee the right to appeal state decisions, these laws will just as probably include their own evasion mechanisms. Similarly, the control of goods has been strengthened since 2001 all while the status of “authorised operators” has been created, which allows certain parties to circumvent the formalities of these tightened inspections. Above all, the legal restrictions on the collection and use of data tell us nothing about how not to disagree with the public policies that emerge from these calculations. next....

14Disobeying, falsifying data, not providing data to the State and thus hindering its ability to carry out the calculations – all of this is a politically interesting solution. In public sectors such as education or employment, State agents choose to disobey and not to collect data about individuals in the name of security, on the grounds that security does not fall under their jurisdiction (Ogien 2010, Laugier and Ogien 2010). This situation appears to be more complex at the borders, for two reasons. For as legitimate in law and in thought as the division of work might be between those who work to ensure security and those with other positions, this division will probably provide less and less structure in professional cultures. The first is that there is a dependence on data: Whosoever fails to provide data does not receive permission to travel, nor are their products cleared for transit; the law has formalised the provision of data as a precondition for movement. Of course, what the law does, the law can undo because of public resistance. However, it will be complicated to ask the people at the border for fewer data points. For as legitimate in law and in thought as the division of work might be between those who work to ensure security and those with other positions, this division will probably provide less and less structure in professional cultures: Security becomes a matter that exceeds the scope of services that have traditionally been involved in this issue and becomes a total social fact. One may wish for it to be different or try to challenge it, but this intersection of state functions does not necessarily raise issues beyond the purview of the officials tasked with implementing these policies. The second reason for the challenge of disobeying at the border is because of its particularity: A border is simultaneously a place of state control and an economic resource precisely because there is this control. The control and the procedural complexity that it creates form part of the knowledge and know-how that private players are peddling at the border (agents, transporters, logistics managers…). As such, it is highly probable that the border players, whether private or public, are relatively supportive of data collection. next...

15A third option is rarely discussed: adopting the language of calculation in order to challenge its results. Our position is that it will be difficult to change the direction of state action from outside the realm of calculation. Using the language of calculation does not mean that utilitarian thinking has to be adopted or that individuals have to surrender to calculation in order to change their behaviour. Using the language of calculation simply means recognising in the calculation a human practice that is not exclusively reserved for a form of government. Our position is that it will be difficult to change the direction of state action from outside the realm of calculation. Jeandesboz et al. (2013) use this language. They study the feasibility of a proposal by the European Commission regarding the EU’s external borders (the Smart Borders package) and demonstrate the extent to which these programmes can entail significant and sometimes runaway costs. However, they do not compare these proposals with other possible policies, which is probably not what was expected of them, but it might be interesting to do so. Thus, with regard to migration policies, two criticisms are possible on the basis of calculations. On the one hand, one could be surprised that the spirit of calculation was not applied to migration policies as it was in other fields, namely by conducting cost-benefit analyses that compare the various possible public policies with each other, including open borders, without any preconceived notions. On the other hand, the concept of acceptable risk could also be debated. Thus, there is a general question that might concern us all: Is my daily security worth all of this? “All of this” refers not only to the egocentric issue of the invasion of my privacy but more generally to the infringement on my life, the lives of others, of emigrants, of newcomers and even of those who live far from our borders but are being bombed in the name of keeping me safe at home. With respect to goods, there is a growing demand for firm-level data in order to fine-tune trade policies (Cernat 2014). The United Nations reference database, UN-COMTRADE, which is publicly accessible and where countries send their external trade statistics, provides data per month, while until very recently the annual level had been the standard reference. However, this is still not enough. There is uncertainty about the reasons provided because they are the result of very different factors: a tradition of secrecy surrounding the activities of the State in general, support from major economic players who wish to preserve the confidentiality of their transactions (and probably not to make it easy for administrations combatting international fraud), people’s low level of awareness regarding taxation and international trade issues, and technical problems related to the sharing of data that are precise enough to be useful at the individual level (for businesses), all while preserving the anonymity of legal entities, namely importers and exporters. Admittedly, the G8 countries in 2013 committed to making all their data available, by default, thanks to the G8 Open Data Charter. But besides the fact that it concerns just eight out of more than 180 countries in the world, the results are very inconsistent (Castro and Korte 2015). The Open Data Index (a new ranking) does not include any data on trade or border management. And more generally, there is nothing on the functioning of the State, with the exception of the budget, which is a data point that has been public for a long time thanks to finance laws (even the French colonies used to make it public…). In other words, we are far from having reached the end of a State monopoly on the production of knowledge about its own operations. suite....

VI. Conclusion

16The border is a fiction with very real effects, to use the wording of Bourdieu with respect to the State. One can govern secrecy but one cannot govern the invisible. Fences, markers, border posts and maps are all ways to make the border visible and to control it. The mathematisation of the border is part of this very human effort to make borders legible. One can govern secrecy but one cannot govern the invisible. Fences, markers, border posts and maps are all ways to make the border visible and to control it. The border is a marker of discontinuance between those who govern and those who are governed. The power relationship between those who govern and those who are governed no longer develops on the territory alone but is rooted in knowledge of the relationships between territories. The governance of borders is produced in international fora, and states’ control has spread out, through the control of data, beyond the limits of their national territories. This power relationship is unequal, but the inequality is not technical in nature: Economists have models in their disciplines that are circulating outside any “government control”, hackers also have their encryption and security tools that permeate the public at large, multinational corporations have their data-mining tools, and, generally speaking, people know and understand what is possible. The problem of criticising governance lies in the relationship that we cultivate with the language of calculation, which we falsely attribute to a capitalist ideology and a neoliberal mode of government. When Diderot criticised William Petty’s political arithmetic, he already proclaimed this science to be dangerous if it is meant solely for the king. And yet, the more states ask citizens for data, which is the case today, the more citizens can legitimately ask the states for data. The same applies to state interests, if the State wants to prevent civil disobedience, the falsification of data and other avoidance strategies and not find itself having to govern more and more in secret, which would run counter to the idea at the core of governing by numbers, the rejection of unquestionable authority. This criticism of contemporary digital governance should not have anything “virtual” or “technological” about it. It is not a matter of digital rights or of borderless citizenship on the Internet: Those who want to flee, to try, to create, to learn, to love and to trade have ambitions that go beyond what is possible on the Internet. They want to do it all there, now, in this world of borders. next....

Bibliography

17

Amoore, Louise, 2006, “Biometric borders: Governing mobilities in the war on terror,” Political geography 25 (3), p. 336-351.

Amoore, Louise, 2011, “Data derivatives: On the emergence of a security risk calculus for our times,” Theory, Culture & Society 28 (6), p. 24-43.

Andrejevic, Mark, Gates, Kelly, 2014, “Editorial. Big Data Surveillance: Introduction,” Surveillance & Society 12 (2), p. 185-196.

Besley, Timothy, 2015, “Law, Regulation, and the Business Climate: The Nature and Influence of the World Bank Doing Business Project,” Journal Of Economic Perspectives 29 (3), p. 99-120.

Bigo, Didier, 2016, The Möbius strip of national and world security, http://mappingsecurity.net/blog/the-mobius-strip-of-national-and-world-security/ (accessed 18th May 2017).

Bigo, Didier, 2006, “Security, exception, ban and surveillance,” in David Lyon, Theorizing surveillance: The panopticon and beyond, Routledge, p. 46-68.

Borot, Luc, 2002, “GouvernanceCités,” (1), p. 181-186.

Broeders, Dennis, Dijstelbloem, Huub, 2015, “The Datafication of Mobility and Migration Management: the Mediating State and its Consequences,” in van der Ploeg, Irma, Pridmore, Jason (eds.), Digitizing Identities, Doing Identity in a Network World, New York, Routledge, p. 242-260.

Broeders, Dennis, Schrijvers, Erik, van der Sloot, Bart, van Brakel, Rosamunde, de Hoog, Josta, Hirsch Ballin, Ernst, 2017, “Big Data and security policies: Towards a framework for regulating the phases of analytics and use of Big Data,” Computer Law & Security Review, 33 (3), p. 309-323.

Brun, Patrice, 2010, Le monde grec à l'époque classique : 500-323 av. J.-C, Paris, Armand Colin.

Busse, Matthias, Hoekstra, Ruth, Königer, Jens, 2012, “The impact of aid for trade facilitation on the costs of trading,” Kyklos 65 (2), p. 143-163.

Cantens, Thomas, 2015a, “Un scanner de conteneurs en « Terre Promise » camerounaise : adopter et s’approprier une technologie de contrôle,” L’Espace Politique. Revue en ligne de géographie politique et de géopolitique (25).

Cantens, Thomas, 2015b, L’esprit de calcul : pour une épistémologie de la marchandise, Université de Reims, département de philosophie (mémoire non publié).

Cantens, Thomas, Raballand Gaël, 2016, “Une frontière très très longue, un peu difficile à vivre », Le nord du Mali et ses frontières,” in Cantens, Thomas, Raballand Gaël, Fragile Borders: rethinking borders and insecurity in Northern Mali, Genève, Recherches et documents : Fondation pour la recherche stratégique. Version anglaise consultable sur http://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/tgiatoc-northern-mali-and-its-borders-report-1793-proof31.pdf

Castro, Daniel, Korte, Travis, 2015, Open Data in the G8: A Review of Progress on the Open Data Charter, Washington, Center for Data Innovation. http://www2.datainnovation.org/2015-open-data-g8.pdf

Cernat, Lucian, 2014, “Towards “Trade Policy Analysis 2.0,” From National Comparative Advantage To Firm-Level Trade Data, Trade European commission. http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2014/november/tradoc_152918.pdf

Clavell, Gemma Galdon, 2016, “Policing, big data and the commodification of security,” in Bart van der Sloot, Dennis Broeders & Erik Schrijvers (eds.), Exploring the Boundaries of Big Data, p. 89-115.

Couvenhes, Jean-Christophe, 1999, “La réponse athénienne à la violence territoriale aux IVe et IIIe siècles av. J.-C,” Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz 10 (1), p.189-207.

Crawford, Gordon, Abdulai, Abdul-Gafaru, 2009, “The World Bank and Ghana's Poverty Reduction Strategies: Strengthening the State or Consolidating Neoliberalism?,” Labour, Capital and Society/Travail, capital et société, p. 82-115.

Cukier, Kenneth, Mayer-Schoenberger Viktor, 2013, “The rise of Big Data: How it's changing the way we think about the world,” Foreign Aff. Vol. 92, p. 28.

Davidshofer, Stephan, Jeandesboz, Julien, Ragazzi, Francesco, 2016, “Technology and security practices: Situating the technological imperative,” in Tugba Basaran, Didier Bigo, Emmanuel-Pierre Guittet, R. B. J. Walker (dir.), International Political Sociology: Transversal Lines, London, Routledge, p. 205-227.

Deleuze, G., Lapoujade, D., 2002, L'Île déserte et autres textes : textes et entretiens 1953-1974, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit.

Diarra, Gaoussou, Plane, Patrick, 2012, “La Banque mondiale et la genèse de la notion de bonne gouvernance,” Mondes en développement (2), p. 51-70.

Dosse, François, 2009, “Les engagements politiques de Gilles Deleuze,” Cités (4), p. 21-37.

Geourjon, Anne-Marie, Laporte, Bertrand, 2012, “La gestion du risque en douane : premières leçons tirées de l'expérience de quelques pays d'Afrique de l'Ouest,” Revue d'économie du développement, 20(3), p. 67-82.

Hansen, Hans Krause, 2015, “Numerical operations, transparency illusions and the datafication of governance,” European Journal of Social Theory 18 (2), p. 203-220.

Hoock, Jochen, 1987, “Discours commercial et Économie politique en France au XVIIIe siècle : l’échec d’une synthèse,” Revue de synthèse 108 (1), p. 57-73.

Hoock, Jochen, Jeannin, Pierre, 1993, Ars Mercatoria: Handbücher und Traktate für den Gebrauch des Kaufmanns, 1470-1820, Paderborn, Schöningh.

Ireland, Robert, 2009, “WCO SAFE Framework of Standards: Avoiding Excess in Global Supply Chain Security Policy,” The Global Trade & Customs Journal, vol. 4, p. 341.

Jacquet, Pierre, 2011, “La recherche en économie sert-elle le développement ?,” L'Économie politique (2), p. 84-92.

Jeandesboz, Julien, 2014, “EU Border Control: Violence, Capture and Apparatus,” Jansen,Yolande, Celikates, Robin, De Bloois, Joost (eds.), The Irregularization of Migration in Contemporary Europe. Detention, Deportation, Drowning, London/New York, Rowman & Littlefield International, London, New York, Rowman & Littlefield International, p. 87-102.

Lemgruber, Andreas, Masters, Andrew, Cleary, Duncan, 2015, Understanding Revenue Administration: An Initial Data Analysis Using the Revenue Administration Fiscal Information Tool, International Monetary Fund.

Leurs, Koen, Shepherd, Tamara, 2017, “Datafication & Discrimination,” in Mirko Tobias Schäfer, Karin van Es (eds.), The datafied society: studying culture through data, Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, p. 211-234.

Lyon, David, 2016, “Big data surveillance: Snowden, everyday practices and digital futures,” in Tugba Basaran, Didier Bigo, Emmanuel-Pierre Guittet, R. B. J. Walker (eds.), International Political Sociology: Transversal Lines, London, Routledge, p. 254-285.

Michaels, Ralf, 2009, “Comparative law by numbers? Legal origins thesis, doing business reports, and the silence of traditional comparative law,” American Journal of Comparative Law 57 (4), p. 765-795.

Moïsé, Evdokia, Sorescu, Silvia, 2015, “Contribution of Trade Facilitation Measures to the Operation of Supply Chains,” OECD Trade Policy Papers, no 181, Paris, OECD Publishing.

O'Neil, Patrick H., 2005, “Complexity and counterterrorism: thinking about biometrics,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 28 (6), p. 547-566.

OCDE, 2015, Implementation of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement: The Potential Impact on Trade Costs.

Ogien, Albert, Laugier, Sandra, 2017, Pourquoi désobéir en démocratie ?, Paris, La Découverte.

Ogien, Albert, 2010, “Opposants, désobéisseurs et désobeissants,” Multitudes 41 (2), p. 186-194.

Parizot, Cédric, Amilhat Szary, Anne Laure, Popescu, Gabriel, Arvers, Isabelle, Cantens, Thomas, Cristofol, Jean, Mai, Nicola, Moll, Joana, Vion, Antoine, 2014, “The antiAtlas of Borders, A Manifesto,” Journal of Borderlands Studies 29 (4), p. 503-512.

Parker, R. H., 1966, “A Note on Savary's" Le Parfait Negociant",” Journal of Accounting Research, p. 260-261.

Rancière, Jacques, 1995, La mésentente. Philosophie et politique, Paris, Galilée.

Redden, Joanna, 2015, “Big data as system of knowledge: Investigating Canadian governance,” in Greg Elmer, Ganaele Langlois, Joanna Redden, Compromised Data: From Social Media to Big Data, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, p. 17-39.

Reinert, Kenneth A., Rajan, Ramkishen S., Glass, Amy Joycelyn, Davis, Lewis S., 2010, The Princeton Encyclopedia of the World Economy, Vol. 1, Princeton University Press.

Régnier, André, 1968, “Mathématiser les sciences de l'homme ?,” Revue française de sociologie, p. 307-319.

Supiot, Alain, 2015, La gouvernance par les nombres, Paris, Fayard.

Uztáriz, Gerónimo de, Véron de Forbonnais, François, 1753, Théorie et pratique du commerce et de la marine, Paris, Vve Estienne et fils.

Valcke, Catherine, 2010, “The French Response to the World Bank's Doing Business Reports,” University of Toronto Law Journal 60 (2), p. 197-217.

Wiener, Norbert, 1962, Cybernétique et société, Paris, éd. Deux Rives.

World Economic Forum, 2014a, Enabling Trade: Valuing Growth Opportunities.

World Economic Forum, 2014b, The Global Enabling Trade Report.

World Trade Organization, 2014, Protocol Amending the Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization - Decision of the 27th November 2014.

next...

Notes

18

1. Thomas Cantens is a researcher at the World Customs Organization (Brussels) and an associate lecturer at the University of Auvergne’s School of Economics (Clermont-Ferrand). The author wishes to thank those individuals who participated in The Art of Bordering (Rome, October 2014) and Coding and Decoding the Borders (13–15 April 2016, Brussels) conferences, where a preliminary draft of this paper was presented, as well as Cédric Parizot and the anonymous reviewers of this paper for their valuable comments. 2. These were war and especially fiscal relationships (Brun 2010). Instead of defending the riches on its territory, Athens embarked on blind expansionism without considering how vulnerable its bases were (Couvenhes 1999). War and peace formed a problem whose solution was not as evident to Plato’s and Xenophon’s contemporaries because no longer waging war was also a sign of decline. 3. The “SITC” (Standard International Trade Classification), the “SH” (Système Harmonisé) and the “BEC” (Broad Economic Categories) are conventions through which any physical objects can be coded as a series of between two and six digits. 4. The term “states” refers to nations or groups of nations that have a government. The term “State” refers to the concept of public authority, a legal and administrative entity, to which the population of a territory is subject. 5. At issue are borders that are “controlled” by states and not by armed groups. 6. In France, the computerised customs system was introduced in 1976. This is not a feature that is unique to OECD countries: The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development started to develop software for developing countries in the 1980s. 7. The WTO negotiations, the so-called Doha Round, were completed in December 2013 with an agreement on trade facilitation. A large number of articles in the agreement refer to the use of data by border administrations: transfer of data relating to the cargo before its arrival at the border; widespread adoption of risk assessment; the distinction of receiving an “accredited” operational status on the basis of operations analysis criteria; the creation of “single windows” where users submit all their data and complete all formalities, which makes it easier to pool the data for use by all state services and thus extends each service’s field of analysis to data that it does not lay claim to for its own formalities but can access nonetheless. See WTO (2014). 8. https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/ports-entry/cargo-security/c-tpat-customs-trade-partnership-against-terrorism (most recent update: 5 April 2017, accessed 18 May 2017). https://www.cbp.gov/border-security/ports-entry/cargo-security/csi/csi-brief (most recent update: 26 June 2014, accessed 18 May 2017). 9. http://ec.europa.eu/ecip/help/faq/ens1_en.htm#faq_1 (most recent update: 7 June 2016, accessed 18 May 2017). 10. In 2014, the EU’s member states received 609 declarations per minute on average (source: DGTAXUD, https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/general-information-customs/customs-risk-management/why-is-risk-management-crucial_fr, accessed 18 May 2017). 11. See Amoore (2006) on the US VISIT (United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology) programme to combat terrorism. With regard to customs, the notion of security is flexible and ranges from fighting terrorism to economic security (for example, the guarantee that competition will not be unfair and that “intellectual property” will be protected) and health safety by ensuring that standards are met. 12. The Ars Mercatoria research project has collected references from all the trade manuals published in Europe between the 15th and the 18th century (Hoock et al. 1993). The term “science of trade” is used to refer to the knowledge built up by these manuals (Hoock 1987). 13. For example, Savary advised traders to entrust their children to their business partners abroad, so that these children could learn the habits, customs and language and be more effective at trade. This goes beyond economic relationships; Savary considers accounting as a way of putting things in order and evidence of an ethic of prudence (Cantens 2015b). 14. The Customs Assessment Trade Toolkit (CATT) for the World Bank (http://www.g20dwg.org//pdf/view/260/, accessed 18 May 2017) and the Revenue Administration’s Fiscal Information Tool for the IMF (https://www.imf.org/external/np/seminars/eng/2013/asiatax/pdfs/masters.pdf, accessed 18 May 2017). 15. See Besley (2015) for a description of this criticism of the Doing Business report. 16. This is a criticism that is often made of the World Bank’s Doing Business and Enterprise Surveys, in which multinational corporations are overrepresented in the selected samples, in particular with regard to countries where the informal sector, including long-distance traders, is important. 17. This is the case with Doing Business, which develops measures for a given import-export scenario (a container, a specified volume, spare parts for cars), http://www.doingbusiness.org/methodology/trading-across-borders (accessed 18 May 2017). 18. See Crawford and Abdulai (2009) and Diarra and Plane (2012) for examples of the influence of rankings on the relationships between donors and governments, and Valcke (2010) for an analysis of the relationships between jurists and economic analyses. 19. Very briefly, it can be said that econometric models have an “explained” or dependent variable – for example, the cost of crossing the border – and a series of variables that are (supposed to be) “explanatory” – for example, trade support, quality of infrastructure, the presence of a website to disseminate legal information to users, the quality of governance, corruption – whose effects are tested on the explained variable in order to identify which ones have a significant effect. 20. See Busse et al. (2012) for a usage example of this measure to assess the impact of aid on international trade. 21. The gravity model models trade flows between countries in the form of an equation that resembles Newton’s law of universal gravitation: The trade flow between two countries is the function of a constant, the economic mass of each country (usually, its GDP) and the distance separating them. See Reinert et al. (2010) for an overview of the history of this model. 22. For example, some of the OECD’s Trade Facilitation Indicators are calculated on the basis of indicators taken from Doing Business, Logistic Performance Index and World Economic Forum (OCDE 2015). 23. Time has been used as a reference for geographical description in other contexts, in particular during colonial conquests, when explorers, soldiers and missionaries described their journeys through Africa not necessarily in terms of metric distance but in hours or days. 24. Doing Business has the same Distance to Frontier notion, which indicates the distance between the country and the best performance in the rankings. 25. This notion of commensurability, which is explicit in the world of objects since it is possible to extract a value from it, finds its counterpart in the idea of normality–deviance, which Amoore (2011) highlights, according to which individuals’ normality is not necessarily self-evident but based on analysing vast quantities of individual data. 26. The IMF’s tool compares administrations in each grouping of countries, which are joined together according to criteria relating to wealth (GDP per capita) and geography (a region of the world). The country’s position is known, but that of the others is not. Naturally, the data processing centre, the IMF, can reconstitute the detailed total ranking. See Lemgruber et al. (2015). 27. See Plato, Philebus, 56e–57a. 28. Lyon (2016) also cites this shift from research into causes to the anticipation of effects that the use of big data brings about. 29. See Geourjon and Laporte (2012) for an application to customs. 30. In a study on governance in Canada with the help of big data, Redden (2015, p. 21) does not point to any particular example of a policy being shaped by these data, nor does she provide any policy that would indicate how these data are to be used. 31. See Galic et al. (2016) for a panorama of the theories of surveillance and their technological evolution. 32. See Foucault (1977:205), in a reprint of the interview entitled “Intellectuals and Power” with Gilles Deleuze, which first appeared in French in 1972 in the review L’Arc: “At one time, practice was considered an application of theory, a consequence; at other times, it had an opposite sense and it was thought to inspire theory, to be indispensable for the creation of future theoretical forms. In any event, their relationship was understood in terms of a process of totalization.” 33. According to Bigo (2006), in the wake of the attacks carried out by al-Qaida on the United States in 2001, broad consent was given to being monitored. Ten years on, it is not evident that much has changed in this regard. 34. The recent decision by the U.S. government to increase the monitoring of passengers from certain countries who travel with certain airlines headed to the United States is further proof of this situation in which governments engage in policies of discrimination under the cover of risk analysis. 35. Bigo (2006) describes the ‘state of exception’ as a mode of government that allows the rule of law to be temporarily circumvented. 36. Governance by numbers is rooted in the advent of Wiener’s cybernetics (Supiot 2015). According to Wiener, “society can only be understood through a study of the messages and the communication facilities which belong to it […] in the future development of these messages and communication facilities, messages between man and machines, between machines and man, and between machine and machine, are destined to play an ever-increasing part” (Wiener 1954:16).

RYBN

The photos in Thomas Cantens’s article were taken by Myriam Boyer and depict ADM8, a work by RYBN.ORG that was exhibited at the School of Architecture in Brussels, La Cambre Horta, as part of the “Coding/Decoding the Borders” exhibit in April 2016 (http://www.antiatlas.net/coder-et-ecoder-les-frontieres-bruxelles-2016/). ADM8 is a trading robot created with the goal of investing and speculating on financial markets. It anticipates trends amid chaotic financial swings and has been buying and selling shares every day since September 2011. It will continue this activity until it reaches the point of bankruptcy. The robot’s activity – its calculations and performance – is monitored, recorded and presented by means of dynamic mapping. http://rybn.org/ANTI/ADM8/ RYBN.ORG is a collective that was formed in 1999 and is based in Paris. http://rybn.org. Its work examines the way in which financialised economies move and how they rely on specialised algorithms and artificial intelligence systems. To this end, RYBN produces “independent research platform for experimental algorithmic trading engineering” and imagines “innovative and counter-intuitive strategies of investment and speculation [that] challenge the neoclassical economics dogma” http://www.rybn.org/ANTI/ADMXI/about/?ln=en). This approach got the collective interested in ways to insert itself in financial trading while disrupting the representations and revealing their irrational side in such a way that the disparity between the economy’s rational demand and its fictional dimension becomes apparent (www.zerodeux.fr/en/interviews-en/rybn-2/). Its most recent research led to an investigation into tax havens, and the outcome of the work is an exhibit entitled “The Great Offshore”, which is currently up at l’espace multimedia Gantner (http://rybn.org/thegreatoffshore/).

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/02-Cantens-the-political-arithmetic-of-borders-towards-an-enlightened-form-of-criticism.pdf