antiAtlas Journal #2 - 2017

Writing as architecture: Performing reality until reality complies

Raafat Majzoub

Raafat Majzoub holds a BA in Architecture from the American University of Beirut and a SM in Art, Culture and Technology from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His work is a negotiation between various disciplines that claim agency over social practice. As an architect, writer and artist, Majzoub describes his work as “performing reality until reality complies”. Through a series of novels, Majzoub creates a spine for an alternative Arab world where his work occurs: The Perfumed Garden. His work has been exhibited, published and performed internationally. He is the co-founder of Beirut-based The Outpost magazine and director of The Khan: The Arab Association for Prototyping Cultural Practices. His thesis A Lover’s Discourse: Fictions (MIT, 2017) hypothesizes a relationship between the dweller and the land that is similar to that of the lover and the loved one, and assumes the act of loving as a model of citizenry. This article is a condensed prelude to Majzoub’s thesis A Lover’s Discourse: Fictions written at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2017, and scheduled to be published by The Khan in 2018. For antiAtlas, Majzoub exhibits two key concepts in his work, Active Fiction and Dormant Fiction, incorporating excerpts of his novel The Perfumed Garden: An Autobiography of Another Arab World (in grey) as well as visuals and project documentation.

Keywords: Active Fiction, Dormant Fiction, Publication, Performance, Arab Politics Definitions:

- Abaya: a robe-like dress, worn by some women in parts of the Muslim world including in North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula

- Hadja does not exist in the text, but rather Hajja: a title given to an older woman or a woman who has performed pilgrimage (or Hajj) to Mecca

- Majlis: a place of sitting, usually used in the context of a "council"

The Beach House, image from the movie, Roy Dib, co-author Raafat Majzoub, 2016

To quote this paper: Majzoub Raafat, "Writing as architecture: performing reality until reality complies", published on December 10, 2017, antiAtlas Journal #2, 2017, Online. URL : www.antiatlas-journal.net/02-writing-as-architecture-performing-reality-until-reality-complies, accessed on date

"To my grandmother, every man is a universe within a universe where every other man and thing lives. […] In her universe, everything required a bold leap of faith. Reality was not factually shared or communicated." - The Perfumed Garden.

I. Introducing Active and Dormant Fictions

1All our memories come from the same place. That was what the imam (Majzoub 2014, final paragraph) was talking about. That was what Omar did not understand. Everyone on the roof waited for Omar to forget that he needed to remember. They didn’t wait like Arabs usually wait – flaccid. Everyone went about their own lives. Nothing stopped. There was too much life in this parking lot on ‘Meedan el Opera’ (Seif 2014) for anything to stop. next...

2All our memories come from the same place. This text is the fabric of two texts, woven into each other in a conversational pattern. These two texts, one composed from extracts of a novel (The Perfumed Garden) and the other written as an explicatory text for the purpose of this piece, are conversing with each other, sometimes delicately, sometimes discrepantly. They can be read both together and separately. This fabric is an instant in understanding agency within a grander terrain: it reflects my quest, the quest of an Arab artist, and more generally an Arab producer, to participate in the making of his world at a social, economic and political level. At the core of this is a question of agency, the agency to manifest things that may not fit in acknowledged realities, supposed oddities, into the public: things that, by merely existing, could morph that public. To create fictions that are designed to flood into realities with a potency that will adjust these realities. In this context, ‘making’ becomes an act of ‘publication,’ the production of something which becomes public and therefore dilutes the existing public. To create fictions that are designed to flood into realities with a potency that will adjust these realities. To rearrange borders. To re-narrate stories. To tell new stories. And to create new places in which stories incompatible with existing stories can flourish. For now, this further complicates my relationship with research. The inclusion of the recent and distant past requires an admission of memories belonging to some of the very realities from which I claim my fictions are designed to reclaim territory. So do I approach such memories with hostility or could we think of this as a democratic duel, where realities are accepted as fictions, empowered fictions, able to dock themselves–maybe not so wholeheartedly–in a harbor away from obligations of logic, reign and jurisdiction? Could they, then, meet their potential successors? As this piece weaves a novel, an explicatory text and visual evidence together, it is enacting its proposal that reality is merely manifested fiction, in this context called Active Fiction, activated and manifested through its adoption by a power structure. Dormant Fiction is a system of logic that may or may not transform into an Active Fiction; such a transformation would depend on a network of power adopting it. Reality is a state of existing in an arena of enacted fiction. Reality is not the opposite of fiction. It is not non-fiction. Perhaps it is possible to envision a form of discourse about constructive fiction through a discussion about memories and futures negotiating the same place in a cycle of Active and Dormant fictions. This could allow for a consideration of another “same place” that presents an inhabitable, non-violent multitude of modalities that would allow for thriving growth outside of democracy. next...

Video below: Raafat Majzoub, E7, 2014

3Two women were helping each other adjust their glittering headscarves at the door of the staircase leading down to the Meedan. One of them shouted, “Zucchini, Condoms, Mahmoud Darwish… Anyone need anything from the outside world?” They had told everyone they met together that they both forgot how they met each other. That, of course, was a lie. They met at the Horeyya, a café called Freedom in downtown Cairo when Amira was hunting tourists to fuck. Amira thought Egyptian cock was too pale. Admittedly, she was a hypocrite. She only came to the brown Cairene genitalia she dismissed; yet she kept looking for glistening blond pubic endeavors to ride. next...

II. The Khan: The Arab Association for Prototyping Cultural Practices

5Throughout the process of writing The Perfumed Garden, it became clear that this “other” constructed world would need a governing force, an entity of organization. For that reason, The Khan was born. Mentioned more than a hundred times in the novel, The Khan, registered as an NGO in Lebanon by the official name The Khan: The Arab Association for Prototyping Cultural Practices, is the materialization of The Perfumed Garden’s fiction being activated. It is a venue for policy research and urban-scale projects rooted in the act of writing as architecture. As we delve into The Khan, we can explore the poetry of methodology, encompassing all its projects and itself as a currency, whose repetition, overlap, weave and networking raise its value and activate its fiction. The institution of The Khan as a registered entity also allows this performance to enter and explore the realm of the transactional and the economy of fiction, and therefore place a spotlight on currency both literally and conceptually. As we delve into The Khan, we can explore the poetry of methodology, encompassing all its projects and itself as a currency, whose repetition, overlap, weave and networking raise its value and activate its fiction. Reading Maurice Blanchot’s Forgetful Memory through the lens of Active and Dormant fiction reinforces the value of this poetic. “Poetry makes remembrance of what men, peoples and gods do not yet have by way of their own memory” (Blanchot 1969) ou (Blanchot 1993, 314).

next....

6“Take me to Hamra,” Horeyya said, “The Hajja needs to make a wish.” I am interested in the poetry of the economy of fiction. And following up on Blanchot’s positioning of poetry, the economy I’m interested in is made of a weave of active artefacts on its own that are continuously regenerated and retold, rather than a remembered ruin of another system. What is generated in this case would not be a monetary networking or interpretation of fiction, but rather the production of a currency outside capitalism. next...

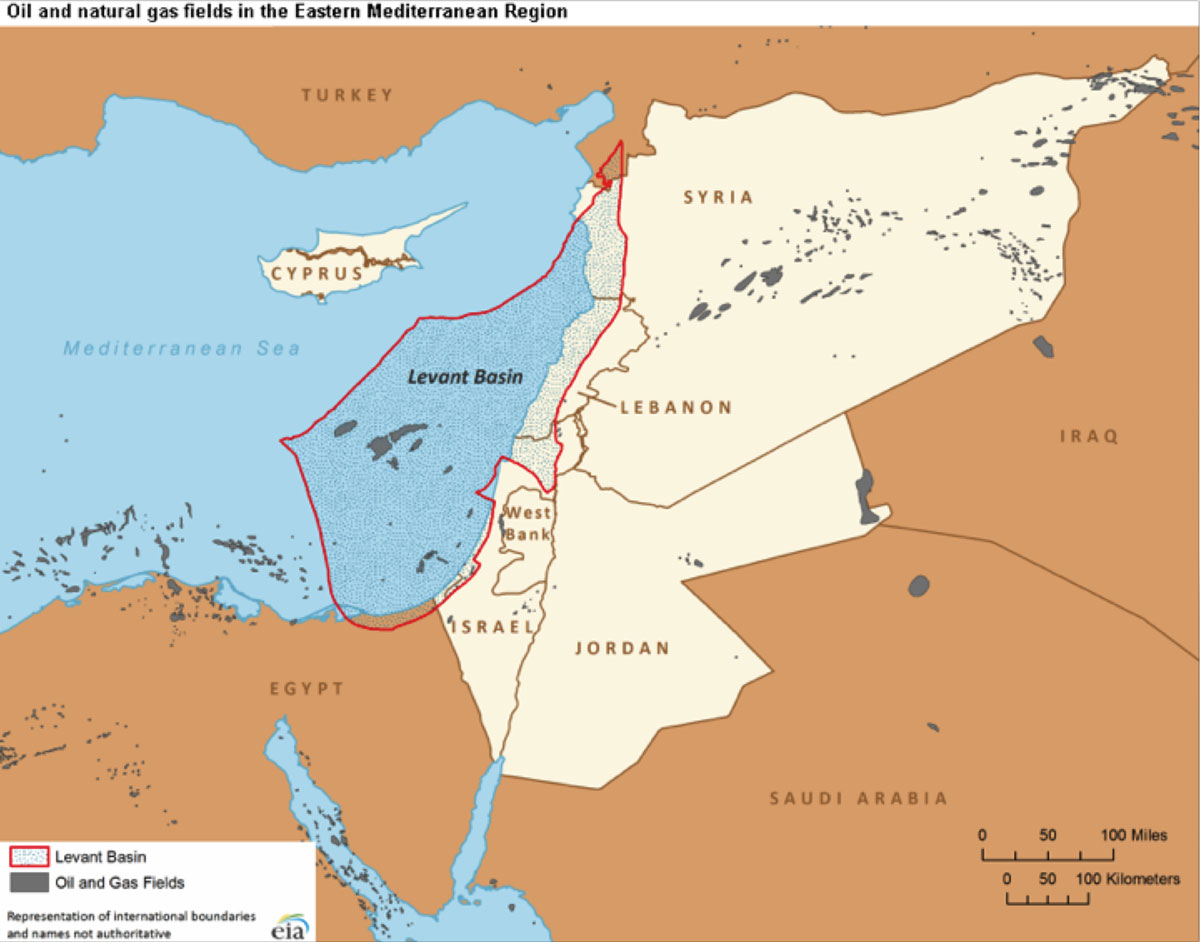

4Amira and Horeyya are two characters in a fiction trying to transcend itself. The Perfumed Garden: An Autobiography of Another Arab World is not a novel that wants to be printed and read, but rather published (made public). By performing an “autobiography,” it is enacting a supposed log of things that had happened according to “another” version of a place that is the Arab World. It identifies its borders as different from the original’s, and claims territory, claims public. In The Perfumed Garden, geopolitical borders that have been assigned by the Active Fictions of European colonial and mandate powers which controlled the Arab World until as recently as the mid-twentieth century do not apply. They are actively challenged with every stride of the narrative. The Perfumed Garden’s duel is with fictions such as The Future of Palestine memorandum, the Sykes-Picot agreement and other proposals that claimed territory through linking themselves to power. The Perfumed Garden does not propagate the impotent victim role that stereotypes and conditions the Arabs into complacency, and stands in conflict with Arab Nationalism, Arabism and ongoing nostalgia for successive, yet distant, Arab Golden Ages. While The Perfumed Garden’s Active Fiction may seem to advocate a view of the Arab World as one nation, what this fiction tries to argue is borderlessness as terrain as opposed to borderless as unity. Inside The Perfumed Garden, this discrepancy between the old borders and the proposed weaves, and the differentiation between an unobstructed terrain and a consensual unity makes space for a conversation about the borders of so-called realities and the potential effect of their absence. It allows the characters, this other world, and myself as an artist to perform reality until the reality of the current world complies. The Perfumed Garden’s duel is with fictions such as The Future of Palestine memorandum, the Sykes-Picot agreement and other proposals that claimed territory through linking themselves to power. This performance is what “writing as architecture” defines. It takes from architecture the inherent relationship between the sketchbook and the “real” or “manifested” world, where an architect sketches to build a structure in public as opposed to the sketch being the final product. And it takes from writing the freeform summoning of conceptualization that does not conform to gravity or any binding “reality”. Writing as architecture becomes a model for articulating constructive fiction, a loophole of agency within existing power structures that are designed to eliminate fictions that don’t conform to their regulations: to oust Dormant Fictions before they become threats. And here is where the weave becomes important. To compete with an Active Fiction, whose patronage can range from the living room of a household to a government’s jurisdiction, Dormant Fictions should create networks and gain momentum through their relevance to everyday life. A singular text is not enough. To create some effect on the landscape and become manifest, a fiction should arm itself with a stubborn weave that further generates, governs and sustains it. next....

III. The Wishing Fountain

7Young shoe shiner boys cleaned the white body of Hamra’s wishing fountain everyday. The boys emptied buckets of water and scrubbed this aging body using theater props from Masrah Al Madina next door. Glistening, sweaty Mohamad, Ahmad and Mustapha take turns at stealing pieces of leftover glamour from the rundown theater underground. suite...

8The Wishing Fountain, as an art installation bringing an accessible, performative object into public, problematizes this currency in 21st century Beirut, a city that Lebanese novelist Elias Khoury describes as “a city of refugees”. As true as this may be, it is an intimidating city that pushes people out. Beirut’s surrounding belt is a series of ethnic, religious and socio-economic enclaves of refugees, migrants and relocated citizens. With over a million Syrian refugees since the beginning of the conflict in Syria entering Lebanon, (knowing that the entire Lebanese population is only five million with over a million under the poverty line) Beirut has become more intimidating. The city runs on the residues of a crippling post-colonial, post-mandate Active Fiction inscribing it within a highly racist, hierarchal and capitalist market state. The basic posture of Beirutis as well as Lebanese people in general is a superiority complex against other Arabs, and even that the Lebanese Arabness is debateable altogether, with a more cosmopolitan fiction offering itself in its place; Beirut being sometimes referred to by the international community as the “Paris of the Middle East”, etc. The situation is complex, and when this fiction is challenged by a situation requiring empathy towards said Arabs at the expense of personal comfort, it gets messy. The influx of Syrian refugees did not look good for Beirut. The Wishing Fountain was installed as the already boiling streets witnessed more verbal and physical assault between the host city and its people, and refugees, who were in one way or another trying to survive without infrastructure. It’s hard to pin down a means of dealing with such a situation within the Lebanese context, where the Palestinian refugee crisis demonstrates a failed scenario the country is suffering from; partly as it is raised as a case study which shows no one to be welcome, regardless of the truth behind the hostility. The Wishing Fountain was installed as the already boiling streets witnessed more verbal and physical assault between the host city and its people, and refugees, who were in one way or another trying to survive without infrastructure. Beirut is an interesting example of a scenario where several conflicting Active Fictions coexist in the same place and are continuously fighting for space. It is helpful to think of the Active Fictions as objects floating on a water surface which is too small to hold them all. These objects vary in form and buoyancy depending on their shapes and sizes. Imperfect, irregular shapes leave gaps between them, that if filled with new objects might change the landscape altogether. These new objects could be inserted in this constellation from outside this water surface, or could float up from beneath, where Dormant Fictions are submerged, waiting for a potential drift upward. This image is helpful as it both clarifies and complicates the idea of Active and Dormant Fictions. On one hand, it allows us to visualize a scenario where an environment’s dominant visible [floating] objects change as competing floating objects are introduced. On the other, we can’t help but ask why these floating objects have been chosen as the Active Fictions and the submerged objects as the Dormant. We cannot ignore the fact that the properties of the water, the materials the objects are made with and the container hosting them are probably parts of this Active Fiction, with both the floating objects and the submerged objects included in that system of logic next...

9But then are we arguing with gravity? Is gravity an Active Fiction, since we’re including the environment as part of the equation? Can a Dormant Fiction be Activated and put gravity to sleep? Rather than provide any answers, the work here is to create a situation to speak about fiction within the context of it being Active and Dormant, and of non-Fiction being nonexistent. Active and Dormant fictions are not concerned either with truth, reference or truth as reference. They are lenses by which we can read constructs, and methods we can use to create new constructs. They are ways of seeing that admit the potency of making. And they are ways of making that admit their agency in changing the landscape. We also speculate that one of these editing techniques is to introduce objects from another fiction, or objects of other shapes, or objects that don’t fit, within the gaps between the existing objects of a particular system in order to ignite a form of change. And if we go back to our metaphor of floating and submerged objects, we can look at the entire system as a logical entity that is editable instead of thinking of each object as an Active or Dormant Fiction on its own. We deduce, at least for now, that one object alone cannot be a fiction, and that fictions are editable, negotiable systems. We also speculate that one of these editing techniques is to introduce objects from another fiction, or objects of other shapes, or objects that don’t fit, within the gaps between the existing objects of a particular system in order to ignite a form of change. And here’s where The Wishing Fountain comes in. When The Wishing Fountain picks a fight with the capitalist system, it is both admitting that the system is a construct and negotiating an alternative through proposing its own alternative fiction. It does not shy away because it’s an art piece, but rather gains its political currency through being a constituent of a bigger fiction. Its presence and recurrence raises the value of its own currency, and the currency of its system. Backed by a system, The Perfumed Garden, and governed by an infrastructure, The Khan, a sculpture on the street has more potency to inhabit the gap and create ripples that can at least start to shake current Active Fictions. suite....

Video: Shoe shining boys trying to make sense of The Wishing Fountain, Raafat Majzoub 2017

Video: The Wishing Fountain, Raafat Majzoub with Samah Abilmona, 2014

10Hamra moves in gangs of young boys taking shifts at igniting the pity of men bred to “Batwannes Beek" and women bred to play hard to get. “I hope you are healthy,” they say to the elderly. “I hope you become wealthy,” they say to the wretched. “I hope your dreams come true,” they say to the young. They sell wishes to the masses in return for coins and conversations. next...

11Alien to the everyday manifestations of the fiction it’s placed in, The Wishing Fountain becomes a spectacle. A white sculpture that resembles a female beggar with a puddle of water in her lap becomes a spectacle. A sign next to her reads: Make a wish and toss a coin in The Wishing Fountain’s lap. The money is public. If you wish to take some, it’s yours. In English and Arabic. The hybrid name of the project, [The Wishing Fountain - مال عام] which is also written on the label next to the fountain, would simply translate to the Arabic (non-English) speaker as “public money”, the meaning of مال عام. The money is public. If you wish to take some, it’s yours. An object in a city does not cater to everyone the same way. In a way, cater is not an adequate description of its action in public. The Wishing Fountain, like any object in public, exists. It exists with specificities and potencies that propose a choreography, as does any object in public. What is different about the fountain is that it offers a choreography outside the existing one. The Wishing Fountain embodies and enacts the fiction of The Perfumed Garden, not the fiction of Beirut as it is. It does not comply with Beirut’s zoning laws, and unlike the charged, high street windowfronts of the city, it does not require compensation to be experienced. The Wishing Fountain is not connected to the ground and has no form of security. The result of this interruption was a month-long negotiation over space between two incompatible fictions. As a result of changes in the stakeholders, the spectacle shifted from noisy to silent, from academic to streetwise, from mainstream news to social media stories. One of the things to take away from this experiment was that even when the “complete” narrative was not “understood”, the project did not lose its potency. Instead, it functioned within multiple levels of engagement. Local and mainstream news outlets were more interested in spinning an “activist” narrative around this project with headlines such as “Artist Creates Hamra ‘Wishing Fountain’ For Panhandlers” (Trad 2014) and “Interactive art helps those in need of cash” (Nehme 2014). Children illegally working on the street either as beggars or shoe shiners adopted the fountain like a shrine, developing their own stories about it, telling them to passersby and inviting people to make wishes, always making sure the fountain is cleaned and taken care of as they constructed their own economy around it. Domestic workers queued to make wishes as part of their Sunday social outings. ‘Beirut: Bodies in Public’, a 3-day workshop on public space in Beirut used it as a platform for one of its panels. Local musicians busked, using the fountain to raise public money. One of those street performers is Sandy Chamoun, a young Tarab singer from Beirut that enters the world of The Perfumed Garden more than once. In addition to busking near The Wishing Fountain, Chamoun performs Rayya, a character in The Beach House, whose script is partially informed by The Perfumed Garden and vice versa. As she claimed the fountain for an afternoon, appropriating it as her own for an informal performance, she had her own opinions about its relevance on the street. “It’s the wishes [for the future] not the money that’s important here,” she said, staring at The Wishing Fountain, “I don’t know why the newspapers are asking you about the money all the time.” Unimpressed, yet aware of the thrill of mainstream media to create heroes and demolish them in real time, she continues “Is it actually about the money?” The act of wishing, projecting forward an alternative reality through imagination is not a typical constituent of designing the public. The public is usually another border, another enclosure, offering a shared escape from ownership. A temporary escape that is, because ownership in the current Active Fiction of capitalism is the defining force of being. With The Wishing Fountain (Beirut, 2014), The Khan materializes part of this other world, The Perfumed Garden, within an Active Fiction it does not belong to: the policed city of Beirut, the capital of the Republic of Lebanon that is separated on a map from the neighboring Syrian Arabic Republic by a crooked line that curves from the Mediterranean eastward into the desert and then south, before it curving back west, its line of separation from Occupied Palestine. In The Perfumed Garden, this line does not exist. The absence of this border frees The Wishing Fountain from the perils of ownership. The wishes made in front of her remain owned by their wishers. And the money in her lap is owned by everyone. next....

IV. Tarab, poetic seduction and trance as politics

12 From the landscape of things The Wishing Fountain attempts to achieve, such as editing reality with another, offering refugees a monument in the city, competing with the concept of money as a scarcity, and the landscape of perceptions and performances which emerge from this fountain as various stakeholders claim it as part of their story, the one specificity I would like to explore is its ability to create Tarab. Defined as a state of trance and ecstasy usually caused by music, but also used as a metaphor for intense emotion (joy or tristesse), Tarab is a force that has been part of my research throughout my work on The Perfumed Garden. I choose Tarab as a superpower because even within the racial, ethnic and social divides of Beirut (Beirut when speaking of The Wishing Fountain, but this is applicable to the rest of the Arab World), Tarab is one of the few things that could be described as its people’s common denominator. Tarab is something that moves people from one state to another, between their perceived realities and potential, assumed fictions. Through goosebumps, yearning and excessive surges of emotional transcendence delivered by the “Motreb/a,” the performer of Tarab, this music can ignite memories or build new ones. Tarab is something that moves people from one state to another, between their perceived realities and potential, assumed fictions. Through goosebumps, yearning and excessive surges of emotional transcendence delivered by the “Motreb/a,” the performer of Tarab, this music can ignite memories or build new ones. Tarab can offer a way to talk about the poetry of the economy of fiction mentioned earlier. In the process of writing as architecture, and the growing multiplicity of formats [of cultural production] involved in this process, it is crucial to be able to pinpoint and leverage a common denominator that connects these formats together. Tarab’s geography is not bound by geopolitical fictions. Many Arab Tarab singers are household names across the Arab World. Egyptian Oum Kolthoum’s (1904 -1975) funeral was attended by more than four million people—almost the population of Lebanon—and more mourners than were at Gamal Abdel Nasser’s (1918 - 1970) funeral, the second Egyptian president. Nasser, whose main project was to unify the Arab World, was a leader whose fiction got the Arab people closest to a feeling of [temporary] shared dignity, and this by making tangible rather than metaphorical changes to the landscape. He nationalized the Suez Canal, for example, and took Israel to war. In his day, Abdel Nasser used Tarab as a political tool. It is said that “between 1952 and 1960, Kulthūm sang more national songs than at any other time in her life; they constituted almost 50 percent of her repertory, and roughly one third of her new repertory after 1960” (Danielson 1997). After Egypt’s defeat in the 1967 war with Israel, Oum Kolthoum embarked on a concert tour across the Arab World to lift the national and Arab pride that was at an all time low. She requested local poets in each country she visited to supply her with lyrics to sing, and performed benefit concerts raising more than two million dollars for the Egyptian government Her Thursday concerts, broadcasted on the radio on the first Thursday of every month, emptied the streets as millions of Arabs were glued to their radio sets (Racy 2003, 73). Abdel Nasser is known to have timed some of his speeches in conjunction with these concerts. Oum Kolthoum herself is known to have described that state of control and evocation she experienced when performing Tarab “as if I were at a school, and the listeners were pupils.” (Racy 2003, 59 & 64). next...

13 This is a place where each and every one of them played an instrument. Each of their parents, like most Lebanese parents of the time, insisted their children played something. It was not a social fiesta, salon extravaganza but more of a necessity. Why? The war. One can blame anything on the war in Lebanon – electric outages, Botox, pollution, unemployment, noisy neighbors, March, homosexuality, the flu and of course, the parental desire for musical offspring. Iman played the violin. Marcel played the oud. Omar played the piano. Thurayya played the harp. Ahmad wanted to play the drums. The sax was more soothing, his mother argued. Ahmad played the sax. Each and every prepubescent one of them played for their nicotine-exhausting parents as households anticipated the worst. As households bought more bread than households could handle. As households lost the war. One can blame anything on the war in Lebanon – electric outages, Botox, pollution, unemployment, noisy neighbors, March, homosexuality, the flu and of course, the parental desire for musical offspring. They never played outside the realm of their mothers and fathers and uncles and aunts. They never played for themselves. As they grew older, their instruments reminded them of nothing but blank bullets of everything they thought would happen. Comfort, revisited. A better future, negotiated. A war they had nothing to do with. They never played themselves out of canons they wore. They never practiced. They smoked before their breasts developed. They smoked before their beards populated. They looked at each other’s instruments through windows overlooking windows, balconies facing balconies. They were neighbors for the longest time, but they only met after Omar pushed the piano off his balcony. It was a cold day somewhere in Beirut. It wouldn’t matter where in Beirut, as every neighborhood dissolves into backstage similes with each and every one of its sisters, as every neighborhood pretends it’s different. Omar had just asked the girl his father chose for him to marry if she was a virgin, right there in the salon where he had played the piano to soothe each and every one of his parents’ traumas since he was seven. His father slapped him as her parents de-colored. He wouldn’t have married her if she was. He wasn’t going to marry her anyways. Omar stood up, and took up his pose, like he would every time he was going to play. Omar smiled. Omar, as everyone followed him closely with their eyes worn of past mourning, opened the abajour with utmost tranquility, stood behind his grandfather’s grand piano, and pushed with all his might. The piano screeched across the terrazzo floor under those ancestral carpets. The piano tilted upwards. The piano tipped over the balcony railing. The piano fell. Omar stood still watching the piano fall. The piano made the best music falling down, the best music when it fell. November wouldn’t have stopped any neighborhood in Beirut from erecting to their balconies, anticipating anything to disturb their pale existence. Everyone came out. Iman came out. Marcel came out. Thurayya came out. Ahmad came out. Each on their balconies watched the piano in become a pile of its pieces in front of the building and Omar smiling on his balcony. Omar won. Omar stood there for a while, then turned his back to the balustrade, walked out of the balcony and into the house. Omar walked outside the house he had lived in for twenty five years as if it was the first time he had ever walked out. He walked down the stairs, then out to the yard where his grandfather’s grand piano lay. In his head, the grand portrait of his grandfather smiled for the first time in its black and white life, and in front of him, next to the piano, a broken violin, a broken oud, a broken harp, a broken sax, and four comrades. They smiled to each other, each knowing they would never be going back up again. They walked away, and as they walked further, they could hear turned off televisions turned back on, and prepubescent music not so different from theirs. next...

14The Perfumed Garden is built on the premise of being a slice in time, rather than a beginning, a climax and an end. The characters are not heroes that know what they are doing at all times, but seem to come and go, as if they are passing by and appearing in the camera’s viewfinder as the photographer (here the writer and the reader) takes the desired picture. In this framing, much happens between the desire and the prospective action; between desiring a particular picture and the click of the camera button. Indecisive characters seduce the photographer until he forgets, a million times over, the picture he is looking for. He either clicks on the camera to take the picture before rolling the film, or forgets to click the button altogether. These indecisive characters transcend the boundaries of the viewfinder, become more interesting than the final picture, and seem—in exchange for the entertainment and perplexion they are offering the photographer—to expect some entertainment and perplexion in return. The photographer (here, the writer), instead of taking a picture, introduces objects that interrupt the flow of these characters in and out of his viewfinder. He introduces objects that make them come more often or leave forever. He puts things in the picture that they have never seen, and watches them learn how to use them, adopt them or let them go. The actual picture becomes unimportant. The initial reason for holding the camera, framing, calibrating and waiting changes. The indecisive, fleeting characters of The Perfumed Garden demand a flexible setting in order to thrive. The actual picture becomes unimportant. The initial reason for holding the camera, framing, calibrating and waiting changes. The indecisive, fleeting characters of The Perfumed Garden demand a flexible setting in order to thrive. The other Arab World being made in The Perfumed Garden, which initially aimed to create a fiction of one nation similar to Nasser’s Arabism, was no longer valid. The characters demand yet another Arab World. next....

15For that first edition of Unus Mundus, five invisible monuments were announced. Each one represented the point of intersection of two cities. Each intersection embodied an edit of the natural and geopolitical realities of the Arab world, creating jumps, shortcuts, or wormholes between two points that were otherwise very far from each other. Each intersection embodied an edit of the natural and geopolitical realities of the Arab world, creating jumps, shortcuts, or wormholes between two points that were otherwise very far from each other. These wormholes had been used by the people of Khan el Thawra for centuries, and their announcement as the first set of invisible monuments was meant to signify the physical and figurative unity of an Arab generation that was going to change everything; materializing liaisons, building bridges, forming tunnels of communication and collaboration in a proposed construction site of tomorrow. “Hahahaha!” Dr. Baz was not impressed with all this unity “crap” as she insisted on calling it, “Liaisons, bridges, tunnels and construction sites of tomorrow, you say?” She picked up her briefcase and left the room. Dr. Baz was one of the most iconic of the Khan el Thawra crop. Like any doctor, she had reached a point where she was bored of people in need, and her once blossoming empathy had turned into a rich and overflowing repertoire of unasked-for satire. next...

16 Not all the characters of The Perfumed Garden know of or agree with The Khan, or stand for The Perfumed Garden as mascots, parading its glory. A lot of them are based on surveyed people that have come into the novel’s fiction in one way or another, and retain their characteristics in The Perfumed Garden. They are people who, in their being, become agents of their own fictions in The Perfumed Garden. Sandy is friendly to the tide of young boys that let her identify herself as whatever she wants. Her character, Rayya, would be friendly to them too. The link between Sandy and Rayya: the performed (Sandy), the blueprint (The Perfumed Garden) and the enacted (Rayya) is a form of poiesis, the procreation of an Active Fiction through a weave that does not deny the agency of its constituents. And as it competes with the fiction of current geopolitics, it is actually proposing a new citizenship, a form of malleable belonging where it’s less about parametric definition (passport) and more about having place to unravel. Consequently, this other Arab World’s borders are neither about unity or terrain. Instead of borders, they resemble membranes of cells that, in proximity, bind rather than delineate, and sameplace — a concept we will turn to next—rather than co exist. Consequently, this other Arab World’s borders are neither about unity or terrain. Instead of borders, they resemble membranes of cells that, in proximity, bind rather than delineate, and sameplace — a concept we will turn to next—rather than co exist. Were this so, in the context of producing space through constructive fiction and Active and Dormant fictions in cycles, our memories and sameplace-ness could become a means of discussing an inhabitable, non-violent multitude that could allow us to grow and thrive outside democracy. suite...

Central image: The Beach House, image from the movie, Roy Dib, co-author Raafat Mazjoub, 2016

17 Hamra is not friendly to the tide of young boys that make her who she is. Mohamad, Ahmad and Mustapha are those children who were blessed with good looks, the invaluable armor for survival around here. Glistening, happy boys become bruised, limping ones with a simple backslap, a kick or a punch in the stomach. People don’t like ugly boys that beg. People don’t like to hear about the problems of other people unless they can step on them like a pedestal onto a stage from which they can talk about their own. On the way to the wishing fountain, the Hajja said nothing. She just looked out of the window into the moving city that changes every day. It has somewhat changed since she last saw it and will always change whether she sees it again or not. It’s inevitable. The cafés that used to listen to secrets of grandfathers-to-be in their youths rarely wait for the secrets of their grandchildren. The Hajja wondered whether it was easier to blame the disintegration of a city on an oppressor, as is the case of her hometown down South. Beirut has no one to blame but herself. “You’re right,” Horeyya interrupted, “Beirut has no one to blame but herself – neither do you.” She gave the Hajja a five-hundred-lira coin and opened the door. Hekmat had parked the car by the Saroulla building right next to the fountain. Mohamad opened the door revealing a white statue of a woman, with a head that looked like the Sphinx, seated on the sidewalk in lotus position. In her lap, a subtle current fed a small pond of water filled with coins, paper money and wishes. Two young girls sat by her side. One looked at the Hajja and stretched her tiny arm and tiny fingers towards her, “Hajja, Hajja! Come make a wish!” She obliged, stepped out of the car and walked towards the fountain. Her colorful abaya danced around with the wind as she stared into the little pond of water in the middle of Hamra. A man passing by picked up a paper bill from the wishing fountain’s lap, and waved it in the air to dry and continued walking. Horeyya closed the door and pointed west. Hekmat drove. suite...

Below, video: Frida makes her wish stresslessly, Raafat Majzoub, 2014

V. Hekmat, a concierge and interlocutor between fictions

18In a first attempt to define sameplace as a concept, a term born in this text as a placeholder and interlocutor of ideas in conversation with each other, Hekmat comes to mind. He is a character in The Perfumed Garden that is always driving. Hekmat mostly drives cars, as a taxi driver or concierge, but he’s a driver in the sense of support just as much as transport. He is one of the major ligaments in the life of The Khan’s main characters. He is a force majeure. Hekmat drives from Alexandria to Tripoli (1,500 km) in fifteen minutes. He escorts characters from different novels in one taxi ride. His unsolicited blurbs of wisdom diffuse conflicts before they happen. Hekmat is one of the least vividly described characters in The Perfumed Garden, yet most of the people that have read the manuscript identify with him quite tangibly. Intrigued by this expression, his potential manifestation as an interlocutor of The Perfumed Garden’s Active Fiction, and Hekmat as a fiction tool to understand sameplace, I decided to explore him further. I started creating venues where I could perform Hekmat, and this is how The Khan’s hotel rooms started. next....

19Omar and Thurayya got into the car, and the first thing Omar thought he’d lose would be his mind, an asset of which the value will be assessed and re-assessed on this journey. As they started moving, Thurayya stretched from the backseat to the radio dial and skimmed back and forth the FM. “What are you looking for?” the driver asked. Thurayya kept scanning until she landed on “Askineeha”, a ballad by one of the most controversial songstresses of Egypt’s deceased Tarab guild, and sat back down. “We could have walked, it’s close, but these guys play Asmahan from four o’clock, and given you’re not much of a talker we might as well enjoy ourselves on the way.” She lit herself another cigarette, and another for the driver. He smiled, Thurayya had that effect on people, then plugged his phone to his radio. “If you like Asmahan, young lady, this is what you need to be listening to,” he said as an impeccable recording of the same song started playing. Thurayya knew everything there is to know about Asmahan. She read. She listened. She collected clippings of things written by people pretending to reveal her secrets. She crosschecked. She rewrote. “What is this?” Her eyes watered. He didn’t pay much attention to her anymore. He was listening. He was listening and taking deep puffs of her cigarette, as he turned right at the Gamal Abdel Nasser memorial statue in Ain elMraiseh, diverging from their route to the Phoenicia. “What is this?” Thurayya asked again, not sure whether she was asking about the sudden change of trajectory or whether that was unimportant compared to her burning desire to know how these recordings existed and why she had never heard them. The driver hushed her, drove up then turned right towards a series of hotels. Omar knew this place. suite...

VI. The Khan hotels

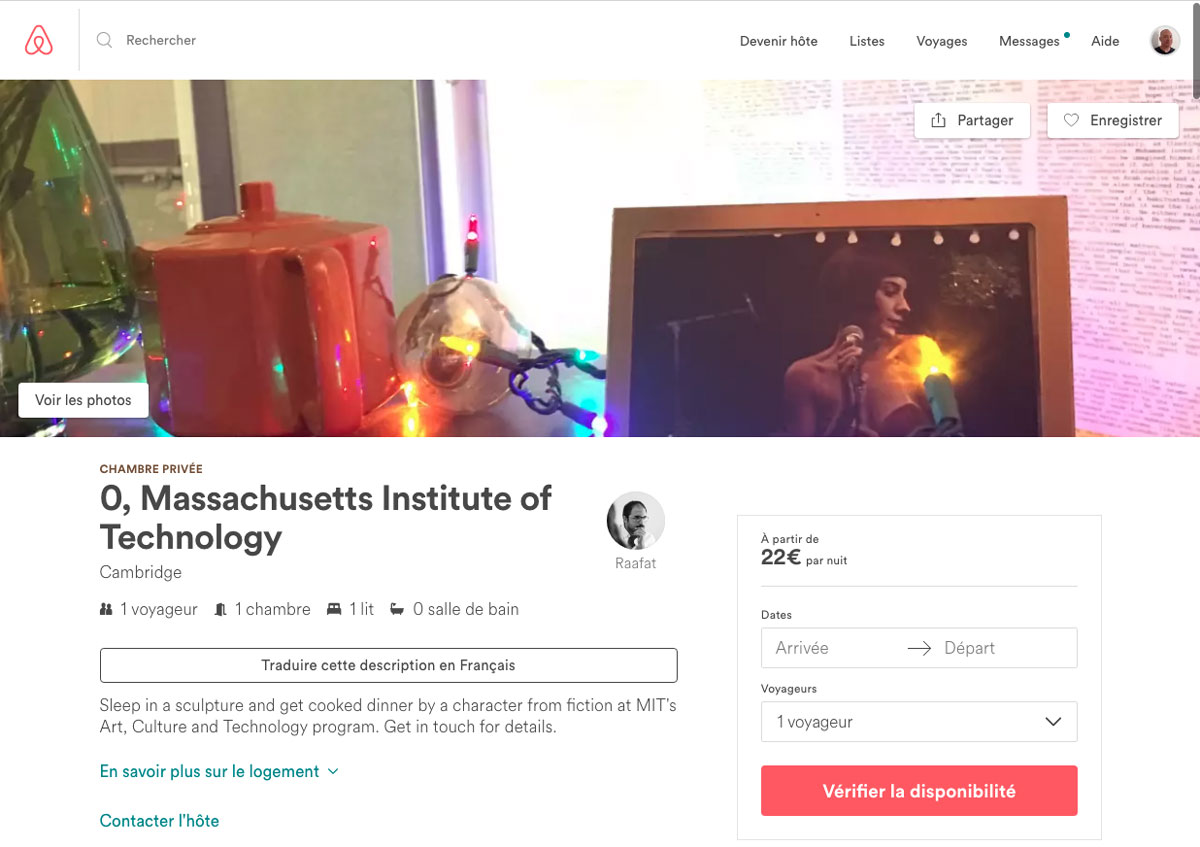

20The Khan’s hotel rooms “0” and “1” at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (USA) and Galerie Ravenstein (BE) respectively are rooms from The Perfumed Garden’s fiction that are temporarily grafted in other Active Fictions. In these rooms—hotel rooms based on spaces and events in the novel—Hekmat functions as a concierge. He welcomes guests and weaves his fiction into their worlds. In these rooms, The Perfumed Garden becomes a landscape, like the framed landscapes of the homeland in houses of diaspora. The difference is that the The Perfumed Garden is a wallpaper made of text, and its homeland is one that is being built, not one that has been migrated from. In these rooms, The Perfumed Garden becomes a landscape, like the framed landscapes of the homeland in houses of diaspora. The difference is that the The Perfumed Garden is a wallpaper made of text, and its homeland is one that is being built, not one that has been migrated from. The wallpaper element is shared in both “0” and “1”. With each iteration, it was a different experiment in engaging with the novel as an editable visual. From a distance, each wallpaper depicts a different floral pattern, but as you get closer, you find a legible text from The Perfumed Garden. In both cases, the wallpapers are proposed as canvases rather than untouchable pieces of art. Scribbles by the performed Hekmat, visitors, and guests edit the landscape, treating it as a draft, a prototype. These spaces are created as intruders and hosts, generators and documentaries — incubators of Active Fiction. They are rooms which cannot be read outside the systemic borders of the world, be they social, economic, or juridical and consequently geopolitical. Like The Wishing Fountain, these rooms have a forensic nature. Through breaching existing Active Fictions, they uncover borders and loopholes in an otherwise opaque system. In the case of “0” which was the first version of these rooms, I transformed my studio at MIT into a space that could be rented through Airbnb. The space was furnished with found and designed objects that manifest The Perfumed Garden’s territory at MIT. The bed, for example, depicts the topography of the Mediterranean seabed in the area of the Leviathan basin where there is an ongoing dispute between Lebanon and Israel over natural gas. It is an invitation to access an inaccessible border through the act of sleep, the collision point for two Active geopolitical Fictions. Sleep is prohibited on campus at MIT, presumably for safety reasons. So is the access of non-affiliated individuals, making “0” tricky to manage within a bureaucratic system that governs through fear, friction and wasting resources. “0” promised, through Hekmat as concierge and chaperone, a penetrative capsule through which conversations about space and fiction could emerge. next...

The Khan's hotel room "1" as seen from the mezzanine of Galerie Ravenstein in Brussels

One of the guests at "1" reading The Perfumed Garden.

US Energy Information Administration,. Boundaries Of The Levant Basin, Or Levantine Basin (US EIA). 2017. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

This image shows the side of the bed, over a television showing a film about The Wishing Fountain. Over the television is a stack of DVDs that are part of The Khan’s growing film collection, and a frame of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the lover of the grandmother in The Perfumed Garden. To the right is a magnifying beauty mirror reflecting a world desk globe with the Arab World’s borders erased using a sharpie, the same technique “obscene” images and texts are censored in magazines in this currently bordered world.

VII. Borders and sameplace / sameplacing

21The second iteration of the hotel rooms, “1”, was much more elaborate in its endeavor. Invited to be part of Moussem Cities: Beirut, a festival in Brussels shedding light on the Lebanese capital, this room functioned as a performance of luxurious intrusion, floating between the playful, serious and offensive tonalities of being present in the world today as an observer of lucid death, migration, xenophobic legislation, the crumbling of unions and disillusionment with present fictions. The starting point thinking about “1” was that I, an Arab man of Muslim heritage, am invited to be in the capital of the European Union, to say whatever I have to say, represent, express, and generalize, within the safety of cultural infrastructure and artistic patronage, when Arab men (and women) like me are denied access to basic needs as they flee wars. Not only this but they spark operations like the EU’s “Mare Nostrum”, that even in its attempt to monitor and organize the flow of refugees into Europe through the Mediterranean, calls that sea “Our Sea” and chooses “tackle” as the most adequate verb to describe its relationship to these people. Through this sameplacing, being affiliated with The Perfumed Garden’s Active Fiction meant more access. A room without a roof, “1” was an invitation to look at everything that was happening inside. Performing Hekmat, I lived in this room for two weeks. As people gazed onto the Arab concierge from above, Hekmat gazed back and broke the surveillance dynamic. In the meantime, Hekmat had more power than the supposed owners of the city, its users, the residents of Brussels. By intentionally designing a room that lacks infrastructure, “1” relied on surrogate institutes for basic daily routines. Hekmat made coffee in Moussem’s office, went to the toilet at Galerie Ravenstein’s shared bathroom, and showered in the backstage of Palais des Beaux-Arts across the street, and so did the hotel guests. Through this sameplacing, being affiliated with The Perfumed Garden’s Active Fiction meant more access. Its currency, even if temporarily for the duration of “1”’s existence, had more value than simply being affiliated with the three institutions mentioned above or even the hosting city itself. next...

22 In comparison to a project like The Wishing Fountain, the hotel rooms of The Khan seemed like fortresses, and a conversation about borders had to be raised again. It is interesting to talk about borders within the context of attempting to understand sameplace as a verb. What does it mean for something to sameplace another? The word initially came about upon a reflection on borders, proximity and The Perfumed Garden’s Active Fiction in relation to co-existence and democracy, both of which are residues of a system it tries to replace. It is this difficult context or near paradox which demands a new means of conceiving the situation; one that takes into consideration the possibility of multi-directional growth arising within and alongside a landscape it seems to defy. Instead of looking at The Khan’s hotel rooms as enclosures, for example, we can assume they are rare venues where sameplacing can happen, with sameplacing accepted as something we’re still trying to understand. Instead of looking at The Khan’s hotel rooms as enclosures, for example, we can assume they are rare venues where sameplacing can happen, with sameplacing accepted as something we’re still trying to understand. These hotel rooms act as scaffolds to induce Active Fiction, to allow various constructions of time and place to seep through the gaps between the borders of what has been established as real. As I suggested earlier when I described an understanding of borders closer to cell membranes than geopolitical delineations, I am interested in analogies between the social/cultural systems of place and the anatomic/physiological systems of organisms. On one level, this could be observed in the direction that contemporary architecture and design is taking towards organic forms, as well as learning from animal and plant physiologies. But it’s intriguing to look at these structures beyond the structural, aesthetic or climatic. Uncannily, skin regeneration research acts as an ideal interlocutor for exploring sameplace in the context of borders and The Khan’s hotel rooms. After substantial wounds or burns skin does not regenerate. It scars. Post trauma, skin (alive) is repaired by a mechanism that creates scar tissue (dead). While previous methods of treating post-traumatic skin loss were based on cosmetic surgery via skin grafts that still left scars on the borders of the graft, Dr. Ioannis Yannas and Dr. John F. Burke, MD “discovered the first scaffold with regenerative activity. This discovery focused on a biodegradable scaffold, a highly porous analog of the extracellular matrix based on type I collagen and incorporating structural features, the significance of which was not understood at that time." The alteration of behaviour that happens on a physiological level once the scaffold is introduced is intriguing when looked at within the lens of Active and Dormant Fiction. Typically, at the site of trauma, new cells are created on the injured membrane. The role of these cells is to close the wound. The cells crawl towards each other from opposite sides of the wound, as if pulling a curtain closed, and seal the wound with a scar tissue that is different in nature to skin tissue. What Dr. Yannas is working on is a dermis regeneration template (DRT), which I’m referring to as a scaffold, that would alter the natural wound-closing mechanism and induce another function yielding a different result. The scaffold, applied on the open wound and covering it entirely from side to side, is designed to create an environment that would confuse the cells migrating towards each other to close the wound. Alternatively, the scaffold provides a template for these cells to rest in place, somewhat halting their desire to reach each other. Confronted with this new reality, the cells change nature. Once rested, the cells start generating new skin cells, instead of the end they desired, which can close the wound with a scar. With time, the scaffold disintegrates, and what remains is the regenerated skin. We can say that the scaffold’s fiction has altered the body’s. We can also say that what we observed as borders of this scaffold (the dimensions of the tissue) were not actually borders, but only appeared as such in the time between their production and their action. As such, The Khan’s hotel rooms are as much sites of synthesis as The Wishing Fountain. next....

23I follow a Lieutenant in the crowd, “Today is Sunday. We leave Aleppo at four o’clock. Tomorrow, Monday evening, you will be in Stamboul.” Aleppo. I am drawn to a building that looks like my grandmother’s in Trablus. It rejects the street it is on, flaunting a green neon sign, ‘Hotel Baron’. I walk towards the first metal door, buzz, and the second, buzz, into the building that looks like my grandmother’s. I enter, looking for the reception. There is none. The overdressed lady at the cashier alternates between vouchering and playing a grand piano behind her. She plays Bagdasarian’s Come on-a My House alternating between a loyal rendition of the piece and other alterations to amuse herself. She only smiles when she plays her variations. suite....

Figure 7: The Khan's "1" bar is modeled after the infamous Hotel Baron bar in Aleppo

24The Khan hotel rooms offer a place to rest. Their fictional borders do not create enclosures where things are incubated, but rather where things sameplace. As concierge, Hekmat takes care of the rooms and entertains the guests. In “1” he enacts a particular tenderness that permeates throughout The Perfumed Garden, a tenderness that can only exist in an autobiography. A specific form of tenderness that births power, and by power births safety while being completely stripped down and raw. This tenderness is one that gains power and traction not through creating a fortress, but through creating a field of intimacy. Of all the people that opened the door to “1” while I was inside the room, more than half took a peek inside and then shut the door quickly and ran away. It was as if they saw something that must not be seen. A man on a toilet, their parents having sex, a crime scene, etc. The rest, upon less than a minute of entering, revealed themselves in the landscape of a materialized autobiography. This tenderness is one that gains power and traction not through creating a fortress, but through creating a field of intimacy. It was as though between the lines of a world’s open letter to them they could find themselves, and want, somehow, their story to become part of that. That effortless desire to feel, inhabit and adopt another template, even un-intellectually, and somehow precisely un-intellectually, is fiction being activated. next....

Figure 8 Both "0" and "1" were available for booking on Airbnb

25 I haven’t seen Zalfa since she taught me how to make sense of the contradicting ingredients of myself while she pressed ‘Record’, and I buried the ruins of Oum Kolthoum with mine. I frequented her mother’s three by three meter den near the lighthouse. Every Mohamad was welcome to have his portrait taken. Her skilled Palestinian hands drew the best and worst in all of us. Her lair was where we were all free, where we could do things the world was not ready to see, and say things our parents were not ready to hear. It was a place to reconnect with the original Mohamad in ways beyond the textbook written on how to love him. I loved Mohamad. Some of his memories are mine. “Memories are like linen straps of cloth that Palestinian mothers wrap around their wounded children’s limbs,” said the Hajja looking into the eyes of her Mohamads, “We all share them.” Zalfa’s mother earned her title, “Hajja,” not by paying a visit to Mecca, rotating around the Kaaba seven times, running from rock to rock and throwing stones at a pole, but rather by becoming a Mecca herself. In fact, her real title “Hijja” means “Reason” or “Site of Pilgrimage,” as she became both to a cult of wandering Mohamads. With time, “Hijja” morphed to “Hajja,” a general term denoting a woman who had performed pilgrimage, and a simpler, more appropriate way to address an old Muslim lady by grocers, policemen, and seaside joggers. Every Mohamad visited her to get his portrait drawn either publicly or in secret. Both ways, Mohamads were looking for something they didn’t know existed. Some wanted to see their prophet in their faces. Others yearned to see their faces through her thick-Kohled Palestinian eyes that knew everything. The Mohamads she liked became her property. Every one of us thought they were her favorite. I was sure I was hers, but so did every other Mohamad in her Majlis. The love she knew and the love she gave is a love only birthed in exile. It is a love similar to that between friends, that pure bond one creates with people beyond their bloodlines. It is a selective bridge created between two people that don’t need to love each other, but choose to. It is a safety net for life after one no longer fits in the nest of their parents. Each of us was looking for this love without knowing it. We were all in exile, named after an invisible prophet, lusting for everything outside the realm of his teachings. suite....

26To prototype cultural practices is to understand the vernacular and to accept and love it. Yet somehow love it without falling in love with it. And not to fall in love with the original, any original, even the vernacular when it becomes an original, and accept the moments of Tarab and the transmutations of Tarab in each body as they happen because they will always happen. Sameplace, sameplaceness and [maybe] sameplacing could be meeting, without the encounter. It could be a perception of something as a memory although it has not been lived before. It is being in a place that looks abandoned even though it has never been inhabited, and feeling the tenderness between here and there and now and then, knowing that they are both the same place. To activate fiction is to offer the simplest format to a desired route, that of allowing and promoting access. To publicate, instead of publish, to make the word public apparent, in the act of putting out into the accessible, potentially shared space. Writing as architecture offers a space to negotiate borders and the supposed capacities of borders to make places. It is in direct conflict with architecture rooted in enclosure, design based on fear or decisions based on history. Approaching architecture within writing and fiction complicates history and the borders between past, present and future. It allows for the birth of things, for the duration of the conversations they were born into. Approaching architecture within writing and fiction complicates history and the borders between past, present and future. It allows for the birth of things, for the duration of the conversations they were born into. With time, “Hijja” morphed to “Hajja”. Sameplace becomes Semplice. The Hajja does not object to her uninformed vernacular, just as semplice won’t. On the contrary, semplice, like Hajja would use its new form to propel what it attempts to signify. In the case of the Hajja, it was easier to approach a pilgrim than to approach pilgrimage. For semplice, Active fiction, this new music, will be performed in a simple manner so that everyone can mumble along. Thank you for reading. Recommended bridges: Adonis. Sufism and Surrealism. Saqi, 2013. Barthes, Roland. 1978. A lover's discourse: fragments. New York: Hill and Wang. next....

Bibliography & web

27 Blanchot, Maurice, 1969, L’Entretien infini, Paris, Gallimard.

Danielson, Virginia, 1997, The voice of Egypt: Umm Kulthūm, Arabic song, and Egyptian society in the twentieth century, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.05912.

Darwish, Mahmoud, 2000, « Sur cette terre », La Terre nous est étroite et autres poèmes, Paris, Gallimard.

Majzoub, Raafat. 2014, « An Opportunity to Imagine a Bright, Green, and Tolerant Lebanon », Al Akhbar, https://goo.gl/E7JU6r (dernière consultation le 4 mars 2017).

Nehme, Stephanie, 2014, « Interactive Art Helps Those in Need of Cash », The Daily Star Newspaper – Lebanon, http://www.dailystar.com.lb/Life/Lubnan/2014/Oct-14/273932-interactive-art-helps-those-in-need-of-cash.ashx

Racy, Ali-Jihad., 2003, Making Music in the Arab World, Cambridge, The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge.

Samuel, Herbert, 1915, The Future of Palestine, Memorandum.

Seif, Ola, 2014, « Cairo's first opera house remembered », Ahram Online, https://goo.gl/USx8pV (dernière consultation le 4 mars 2017).

Trad, Sarah, 2014, « Artist Creates Hamra 'Wishing Fountain' For Panhandlers », Beirut.com City Guide, https://www.beirut.com/l/36422 (dernière consultation le 9 mars 2017).

Web

« Kunstberg - BOZAR – Centre For Fine Arts », Montdesarts.com, http://www.kunstberg.com/en/Bozar-palais-des-beaux-arts

« MECHE PEOPLE: Ioannis Yannas | MIT Department of Mechanical Engineering », Meche.mit.edu, http://meche.mit.edu/people/faculty/YANNAS@MIT.EDU

« Moussem Cities: Beirut – Moussem », Moussem.be, https://www.moussem.be/fr/moussemcitiesbeyrouth, 2-18 février 2017. « Mare Nostrum Operation – Marina Militare », Marina.difesa.it, http://www.marina.difesa.it/EN/operations/Pagine/MareNostrum.aspx

« Programme », 2014, Beirut: Bodies in Public, https://bodiesinpublic.wordpress.com/programme/

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA), « Where We Work », https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/lebanon next...

Notes

1. "To my grandmother, every man is a universe within a universe where every other man and thing lives. […] In her universe, everything required a bold leap of faith. Reality was not factually shared or communicated." - The Perfumed Garden.

2. Majzoub, Raafat. Final paragraph of "An opportunity to imagine a bright, green, and tolerant Lebanon." Al Akhbar English. Accessed March 04, 2017. https://goo.gl/E7JU6r.

3. Seif, Ola R. "Cairo's first opera house remembered." Cairo's first opera house remembered - Photo Heritage - Folk - Ahram Online. Accessed March 04, 2017. https://goo.gl/USx8pV.

4. In this text, ‘public’ refers to common venues and shared spaces accessible by the people. They are considered contested spaces whose structures are not fixed, but rather transform based on the dominant ruling body. The importance of producing something to become ‘public’ lies in its ability to compete with these flexible structures and change them.

5. Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008) is a Palestinian poet considered a national symbol of Palestine and one of the most important Arab poets of the twentieth century. He is imported into the world of The Perfumed Garden as a young poet of the same name in various scenarios, one of which he practices a version of his poem “On this Earth” to an audience at The Khan.

6. Lebanon gained its independence from the French Mandate in 1943 after 23 years of mandate rule

7. The Future of Palestine was a memorandum first presented by Herbert Samuel to the British Cabinet in January 1915, two months after the British declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire. The memorandum influenced a number of members of the British Cabinet in the months preceding the negotiation of the 1916 Sykes–Picot Agreement, and later the 1917 Balfour Declaration.

8. This secret agreement between Britain and France spelled out their roles in the post-war Middle East. It plans the transition between the Ottoman Empire’s Active Fiction in the Levant and the Anglo-French one. It was signed May 9, 1916.

9. Arabism is an ideology advocating the idea of the Arab World through the unification of the countries of North Africa and West Asia from the Atlantic Ocean to the Arabian Sea, and is closely connected to Arab nationalism, which asserts that the Arabs constitute a single nation.

10. Blanchot, Maurice. The infinite conversation. Vol. 82. U of Minnesota Press, 1993. pg. 314.

11. The Perfumed Garden’s fiction does not deny the existence of capitalism and the monetary system, but it aims to incrementally create another system, another Active Fiction.

12. Mohamad, Ahmad and Mustapha are three of the ninety-nine names of the Islamic prophet Mohamad.

13. Elias Khoury described Beirut as “a city of refugees” as part of a talk he gave in Brussels on February 9th, 2017 within the Moussem Cities: Beirut festival.

14. As of 6 May 2015, UNHCR Lebanon has temporarily suspended new registration as per Government of Lebanon's instructions. Accordingly, individuals awaiting registration are no longer included.

15. The Wishing Fountain is an interactive public art project in Beirut by Raafat Majzoub funded by Ashkal Alwan (LB).

16. "Where We Work," UNRWA, accessed March 7, 2017, https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/lebanon.

17. Warda, “Batwannes Beek” (1986, Lyrics: Omar Batiesha, Music: Salah El Sharnobi)

18. Trad, Sarah. "Artist Creates Hamra 'Wishing Fountain' For Panhandlers". Beirut.com City Guide. N.p., 2017. Web. 9 Mar. 2017.

19. Nehme, Stephanie. "Interactive Art Helps Those In Need Of Cash". The Daily Star Newspaper - Lebanon. N.p., 2017. Web. 9 Mar. 2017.

20. "Programme". Beirut: Bodies in Public. N.p., 2017. Web. 9 Mar. 2017.

21. Sandy Chamoun performs the same character ‘Rayya’ in The Perfumed Garden and The Beach House (Lebanon, 2016, 75’, col. Director: Roy Dib, Writers: Roy Dib, Raafat Majzoub)

22. The Beach House. Lebanon: Directed by Roy Dib. Written by Roy Dib and Raafat Majzoub, 2016. film.

23. Danielson, Virginia. 1997. The voice of Egypt: Umm Kulthūm, Arabic song, and Egyptian society in the twentieth century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.05912.

24. A.J. Racy, Making Music in the Arab World, (Cambridge: The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 2003) 73.

25. Ibid., pp. 59 & 64.

26. In the novel, “Unus Mundus” is used as a reference to The Outpost, a magazine of possibilities in the Arab World, based in Beirut. It is the brainchild of Ibrahim Nehme (Editor-in-Chief, 2012 - present) and Raafat Majzoub (Creative Director, 2012 - 2014). The first issue of The Outpost included the first chapter of The Perfumed Garden as a literary supplement using people from the issue’s articles as characters in the novel.

27. Still from The Beach House showing Sandy Chamoun as Rayya.

28. The Khan's hotel room "1" as seen from the mezzanine of Galerie Ravenstein in Brussels.

29. One of the guests at "1" reading The Perfumed Garden.

30. Link to “0” on Airbnb, https://www.airbnb.com/rooms/15424405.

31. US Energy Information Administration,. Boundaries Of The Levant Basin, Or Levantine Basin (US EIA). 2017. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

32. This image shows the side of the bed, over a television showing a film about The Wishing Fountain. Over the television is a stack of DVDs that are part of The Khan’s growing film collection, and a frame of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the lover of the grandmother in The Perfumed Garden. To the right is a magnifying beauty mirror reflecting a world desk globe with the Arab World’s borders erased using a sharpie, the same technique “obscene” images and texts are censored in magazines in this currently bordered world.

33. "Moussem Cities: Beirut - Moussem". http://www.moussem.be. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

34. "Mare Nostrum Operation - Marina Militare". Marina.difesa.it. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

35. “Mare Nostrum” is Latin for "Our Sea", the name for the Mediterranean in the Roman era

36. “Mare Nostrum Operation - Marina Militare". Marina.difesa.it. N.p., 2017. Web. 15 Mar. 2017.

37. "Moussem". http://www.moussem.be. N.p., 2017. Web. 16 Mar. 2017. Moussem organized Moussem Cities: Beirut, the commissioning festival of “1”.

38. "Galerie Ravenstein - Bruxelles Ma Belle". Bruxellesmabelle.net. N.p., 2017. Web. 16 Mar. 2017. “An important pedestrian link between the ville haute and ville basse (uptown and downtown Brussels), the Galerie Ravenstein leads to Gare Centrale. It is incorporated in a huge office building, four storeys high.”

39. "Kunstberg - BOZAR – Centre For Fine Arts". Montdesarts.com. N.p., 2017. Web. 16 Mar. 2017.

40. "MECHE PEOPLE: Ioannis Yannas | MIT Department Of Mechanical Engineering". Meche.mit.edu. N.p., 2017. Web. 12 Mar. 2017.

41. “semplice. /ˈsɛmplɪtʃɪ/ adjective, adverb. (music) to be performed in a simple manner. Italian: simple, from Latin simplex.” Dictionary.com. 13 Mar. 2017.

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/02-Majzoub-writing-as-architecture-performing-reality-until-reality-complies.pdf