http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/03-cecconi-cherici-oniroscope-giving-texture-to-dreams.pdf

antiAtlas Journal #3 - 2019

Oniroscope: giving texture to dreams

Arianna Cecconi and Tuia Cherici

Dreams influence our individual and social lives just as society conditions our dreams. Born out of the collaboration between an artist and an anthropologist, the Oniroscope is both a participatory experience and a survey tool that helps groups of people to explore this relationship while stimulating innovative avenues for analysis and questions about the dream experience and how it is conveyed in our society.

Arianna Cecconi is a researcher in anthropology affiliated with the Norbert Elias Centre, EHESS, Marseille and a lecturer at the University of Milan. Dreams and sleep have been her main topics of study throughout an ethnographic research trajectory that has spanned different terrains (Italy, Peruvian Andes, Spain and, currently, Marseille). For a list of her publications, see: independent.academia.edu/ariannacecconi

Tuia Cherici is a self-taught multidisciplinary artist hailing from Italy who currently resides in Marseille. Her approach combines the tools and mastery of stop-motion film techniques with a radical approach to real-time improvisation. She collaborates on various research projects and showcases her work in Europe, the United States and Japan. www.manucinema.blogspot.com

Keywords: ethnography, visual arts, participative art, anthropology, Marseille, oniroscope, eyes tree, dreams, sleep, North districts, manucinema, interdisciplinary research

Preparation photo of the set of objects for the Oniroscope at "Le Pressing, Galerie de l'école des beaux-arts de la Seyne-sur-Mer", in the framework of the exhibition: Oniroscope - Text and texture of the night dream, April-June 2015.

To quote this article : Cecconi, Arianna et Cherici, Tuia, "Oniroscope : Giving Texture do Dreams" in antiAtlas Journal #3 | 2019, Online, URL : https//www.antiatlas-journal.net/03-oniriscope-giving-texture-to-dreams", last consultation on Date

I Slippery borders

1In his comments on 15th- and 18th-century texts, Norbert Elias reveals how sleep has drifted away from people’s social life over time. While it had been customary in the Middle Ages to welcome guests in rooms that had beds, the bedroom gradually became one of the most “private”, most “intimate” spaces in people’s lives (Elias).

In some societies, dreams underwent a similar process of distancing. They became a part of private, intimate experiences, and the family provided one of the few settings in which they could be shared. Long ignored by the social sciences (Bastide), dreams were considered a port of access for knowledge about the individual rather than society at large.

On a scientific level, interest in the symbolic meaning, the narrative, the text of the dream and its interpretation has sometimes overlooked the particular forms that dreams can take, namely their phenomenological dimension, how we perceive the forms and the colours and how we recognise faces or the meaning of the words and the nature of the spaces.

This article offers a few views and ideas around dreams thanks to a study tool that we (Arianna Cecconi, an anthropologist, and Tuia Cherici, an artist) have created and developed as part of our joint research into night dreams. We call it the Oniroscope. By way of an interdisciplinary approach, our research extends across several different fields. How can people’s dream experiences be observed in a participatory way? How and to what extent can this type of experience be documented? How can society’s dream heritage be catalogued? Because they form an experience whose borders are slippery and don’t fit neatly into spatiotemporal categories, dreams are often difficult to pin down and pose a challenge to us as sleepers and as researchers. They also invite us to experiment with new collection methodologies, as well as new forms of writing.

We will start by explaining how we came to work on dreams in our respective disciplines and, given our particular approaches and questions, how we designed the Oniroscope.

The Oniroscope is a meeting between different groups of participants who come to share the dreams they have at night. Arianna coordinates the sharing activity, which happens at the same time and in collaboration with Tuia, who creates and projects images in real time on video on the basis of the dreams that are being described. The purpose of this interaction is to create a broader language to share the way of perceiving and experiencing dreams and, finally, of putting them into words. In so doing, the fragmentary and the incongruous can also find their place.

In order to highlight the relationship that is forged between the stories of the dreams and the creation of the images, we will analyse what happens at the Oniroscope meetings and describe the effect of these two narrative fictions on each other. We will see that, at these meetings, not only are the dreams implicated in this collective sharing but also the links that we weave between our remembrance of the dreams and the objects of our waking life – between individual and collective imaginations.

Finally, there will be a few attempts to use generic expressions when talking about dreams. What might it mean, for example, to say that “In my dreams, the things I see are blurry”? The recurring forms and the will to express a different kind of knowledge (“I can’t see his face, but I know it’s my father; I don’t see it, but I know I’m being followed”) call into question the nature of the knowledge that our dream experiences convey to us. On this basis, we discuss a supposed boundary between dreams and so-called reality: Dreams do, indeed, influence our individual and social lives, just as our society enters and conditions our dreams and their way of speaking to us.

Although the friendship and interaction that have bound us for 20 years have intertwined our thoughts and tools in an almost inextricable way, the results of our efforts retain a dual nature that we will replicate here in our writing partnership and multimedia documentation.

next...

II. Origins of the research: Dreams and ethnography

2 I was born and raised in Italy in a family where my mother often told me about her dreams and sometimes interpreted them as premonitions. Although I was also affected by some of my own dreams, especially when they happened again and again, I never read up on the subject, nor did I really ask myself about their nature or about the means to interpret them. I lived with my dreams but did not ask myself too many questions about them. It was a lengthy experience in the field in the Peruvian Andes that compelled me to immerse myself in an exploration of the nocturnal dimension. Between 2004 and 2008, I lived for several months among two bilingual Spanish-Quechua peasant communities (in Chihua and Contay) in the Ayacucho region of the Central Andes of Peru. This region was the epicentre of an armed conflict between the Maoist Shining Path movement and the Peruvian Army (1980–1992), and the purpose of my research was to explore the process of local pacification and the different memories people had of this armed conflict. Staying with host families, I participated every morning in sharing dreams from the previous night, and it was then that I realised the role they played in the lives of the Andean villagers during the daytime. For me, dreams became a way to understand the effects of political violence, the dynamics of conflict within the villages, and the process of reconciling not only with the living but also with the dead.

The main distinction that these villages’ inhabitants made was between dreams considered as insignificant (generated by daily concerns, or by having eaten or drunk too much) and those that supposedly carried a message. Another way of formulating this distinction was to speak of dreams coming “from within” (influenced by the day’s worries or thoughts) and those coming “from without”, which are described as a visit from entities (souls of the dead or deities). Only the latter represented a source of knowledge and power, influenced decisions and daily actions, and spread through the community.

The research in Peru, as well as other ethnographies (Tedlock, Perrin, Descola), allowed me to tackle a wide array of conceptions and ways to interpret dreams and the practices associated with them. To date, however, anthropological research has focused mainly on studying dreams in non-Western societies, so-called “dream” societies (Charuty) – that is to say, those that codify the various categories of visionary and dreamlike experiences in great detail, along with their legitimate uses.

Since 2008, I have studied new fields in southern Europe (Italy, Spain, and France) because I wanted to continue exploring dreams in contexts where their place in society is hardly ever recognised. I wondered how people refer to dreams in everyday life in societies like the one I came from, where dreams seem to refer only to the dreamer’s inner self and for which psychology provides the primary officially recognised interpretive framework. Beyond the desire to broaden my research to a comparative horizon, there were also several methodological issues that had to be addressed.

As a subject of research, dreams skirt the limits of ethnographic methodology. This means there is a constant confrontation with a frustration. On the one hand, participant observation collides with the dreams of others, which are impossible to see for anyone except the dreamer; on the other hand, a dream is difficult to convey. The dream experience shatters and destabilises the norms of telling stories. Faced with this frustration, in contexts where there is a shared code according to which dreams can be interpreted, people tend to tell those parts of their dreams that can be related to this interpretive code. In the Peruvian Andes, the phrase “I dreamt of corn” might be considered the only part of a particular dream that is worth sharing. In societies where there is no shared interpretive code, people may have a tendency to condense these parts into a story by weaving a storyline, even though dreams are often characterised by their ability to destabilise the narrative codes and spatiotemporal categories that make a story understandable.

While I was conducting my research, I felt there was a need to approach dreams with tools other than classical interviews and to explore other forms of dream writing that would record them as multi-sensory experiences.

next...

III. Dreams and artistic practice

3 Tuia - Having grown up in the countryside (in rural, Catholic, Tuscany), my relationship with dreams was formed through a combination of “common sense” notions of psychology and local beliefs and codes that were specific to my German mother, as well as the imaginary world of TV, novels, and cinema and the codes forged among friends at school ... But often, the most notable dream memories I had were those that had neither sense nor function – the ones I can’t explain to myself with my nebula of scattered beliefs. It is when I am creating that I sometimes have the feeling that I’m able to catch hold of snippets of my strongest dream experiences. By drawing them, filming a video or sculpting material, I recover traces of that experience. The images created in this way are ones that I regard as documents that “materialise” my memories by using the forms and modes of daily life. These objects and videos are the cornerstones of the process of comparing my experiences with those of other people.

Using dream experiences for the purpose of creation raises questions about aspects that go beyond the values attributed to dreams: nightmares, auspicious dreams, desire, projection, explicit fear ... And yet, these categories do not make it easier to remember the moods, colours, shapes, sounds, actions, particular states of the body, movements ... It’s like life drawing: the more directly the hand follows the gaze on the object, without paying attention to any prejudices one might have in one’s head, the more the drawing is separated from a pre-constituted mental image, enabling one to grasp the shape of the object that is sketched out.

When it comes to dreams, however, it is almost impossible to stifle our judgement, to distinguish between what we think and what we remember – these fragmented images are altered by our memory and by a lack of references in our waking life. The physics, the morphology, and the anatomy of the dimension of dreams do not obey the laws of the waking world. Moreover, if we want to convey our dream to other people by sketching it, we also need to be able to express ourselves in a language that can be understood. And in that respect, if one still maintains some claim to being faithful to the original, one has to be ready for the inevitable deformation that all communication entails.

But what really remains of a dream in the creative work it inspires?

As far as I am concerned, its substance is forever hidden and inaccessible in the depths of our souls. But the task of getting as close as possible to its modes, forms, and appearance can open our hands and our thoughts to a new way of forging relationships between things and the images we make of them. This is how dreams help us to deconstruct and to unmask the stereotypes of our perception of reality and to strengthen the links between our imagination and our day-to-day lives.

next...

Excerpt from a music video,They're seen from other places, music by Stefano Scodanibbio et Thollem McDonas, 2010, Die Schachtel Zeit New Composers

4The goal of creating according to a dream is also explained in more practical terms. One of my dreams dates back to 2005:

“In my dream, I feel that I’m being liquefied bit by bit. It’s both exhausting and sweet; I hate it that I am flowing everywhere, but I can’t help but surrender to this dissolving force...”

Some of the questions around this memory that may help to turn it into a video:

What is there in my waking reality that might evoke such a sensation? What kind of materials can I use to express this strange state of having my body liquefied, which is inconceivable in reality but nonetheless now strangely familiar because I perceived it in a dream?

I started by melting wax, manipulating it and using the camera to capture its movement and texture under a warm light. However, beyond some very suggestive results, the wax forms gave me nothing more than a cold, inhuman sensation. Its melting had nothing to do with the soft flesh of my body being liquefied. In addition, while I undertook the work, none of the ideas in my head relating to wax (mortuary masks made of wax, wax museums, church, depilatory wax, furniture polish...) reconnected me with my dream.

So I sought out other materials, always looking for links between my memory of the dream and the objects I encountered: ice cream, gum, mozzarella, sugar... Every comparison gave me clues as to the nature of the liquefaction that I had dreamt about. Finally, I found butter melting in the sunlight, its consistency fatty, iridescent, supple, and animal. I made a model of a head out of butter because my memory was reduced to the sensation of my cheeks and my forehead flowing off me. I saw my head spread on a pillow, my ears melting...

I filmed how a hair dryer made this butter head melt, which reminded me of the absence, in my dream, of any particular heat or ventilation. But I accepted this incongruity in view of the practical necessity of bringing the melting, the inner light, the filming and the movement of the head all into harmony and having them happen at the same time.

In some respects, although it has taken on an increasingly autonomous identity, the result is similar to my dream.

In this case, what remains of the dream is an awareness of the different melting qualities of the substance, what connects organic matter in terms of texture, processing capacity, and heat, and what certain states and transformations evoke in my imagination.

While it is melting, the butter’s very tangible and terrestrial fat content becomes transparent, and it sparkles with a white light that is out of this world. It loses all resistance to form: the face’s eyebrows sink, giving it an expression that is as much of suffering as it is of relief. When I saw it during the filming, I thought, “It’s like dying, and it’s like giving birth.” While I was thinking this, the butter head was already becoming a lake of peaceful white liquid. I also stopped thinking ... The material was ‘explaining’ to me, in its own way, the sensations of my dream.

It is this type of knowledge by analogy that I seek to collect by connecting the imagination with real matter. I use the eye of the camera to better isolate the elements that interest me and give free rein to the construction of points of view, associations of ideas, and narratives based on its texture, shape, and meaning.

next...

IV. The Oniroscope apparatus

5 For many years, the two of us have been interested in and inspired by each other’s work. We have shared our readings, thoughts, and night dreams. In 2010, our paths began to intertwine. Our objective, which led us to develop our own methodology, was to get out of the “bilateral” interview setup, to interact with different groups of people, to talk about and to work on dreams through a broader use of language (discussing, assembling objects, creating images, video, and writing...).

One of the aspects we wanted to explore together was the relationship between individual dreams and the imagination as it relates to collective experiences. It is a question not only of identifying the possible correlation between dreams collected one by one but also of observing the discussions and the dream narratives that can emerge from having a collective dialogue. We came up with a way for people to share their dreams that allows attention to be drawn to the dream material itself, beyond interpretative keys and psychologising discourse, and where everyone’s dreams can communicate with each other.

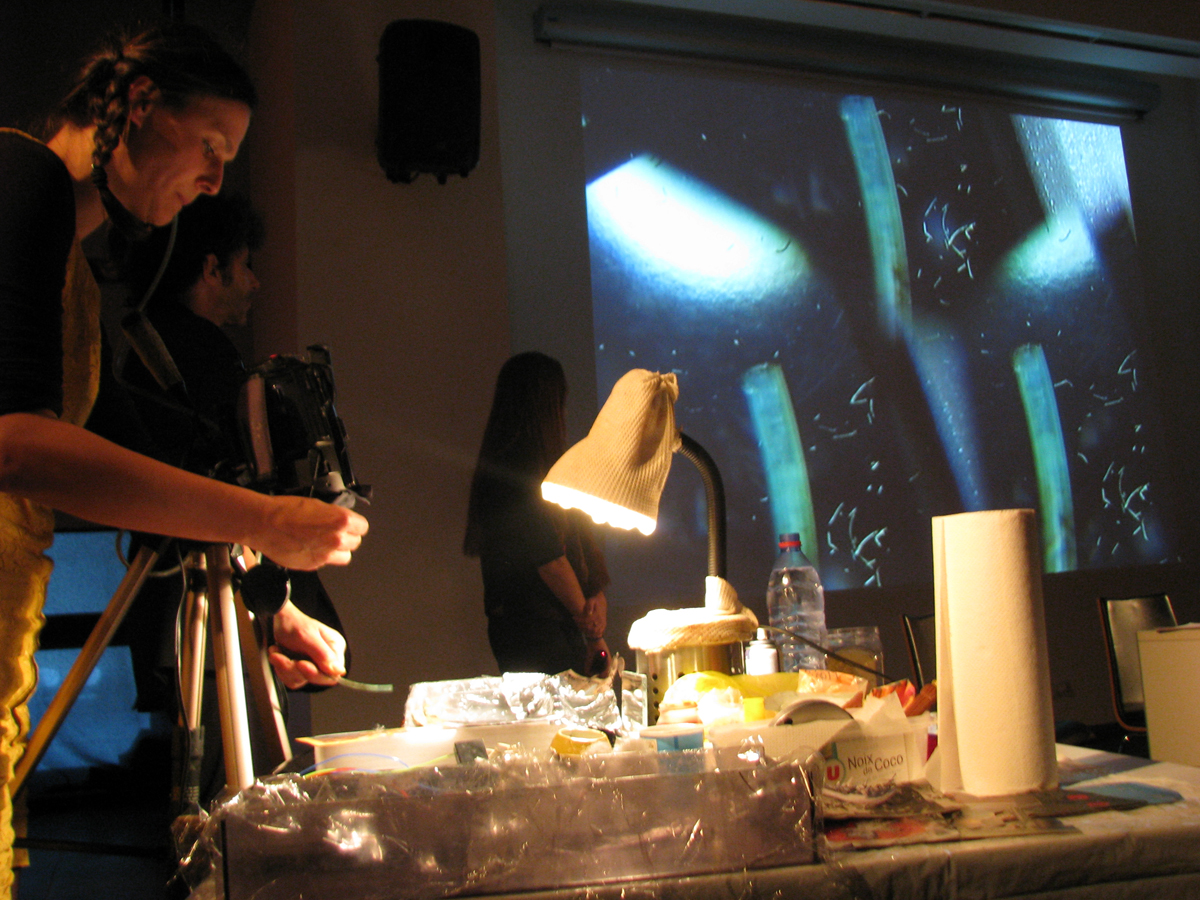

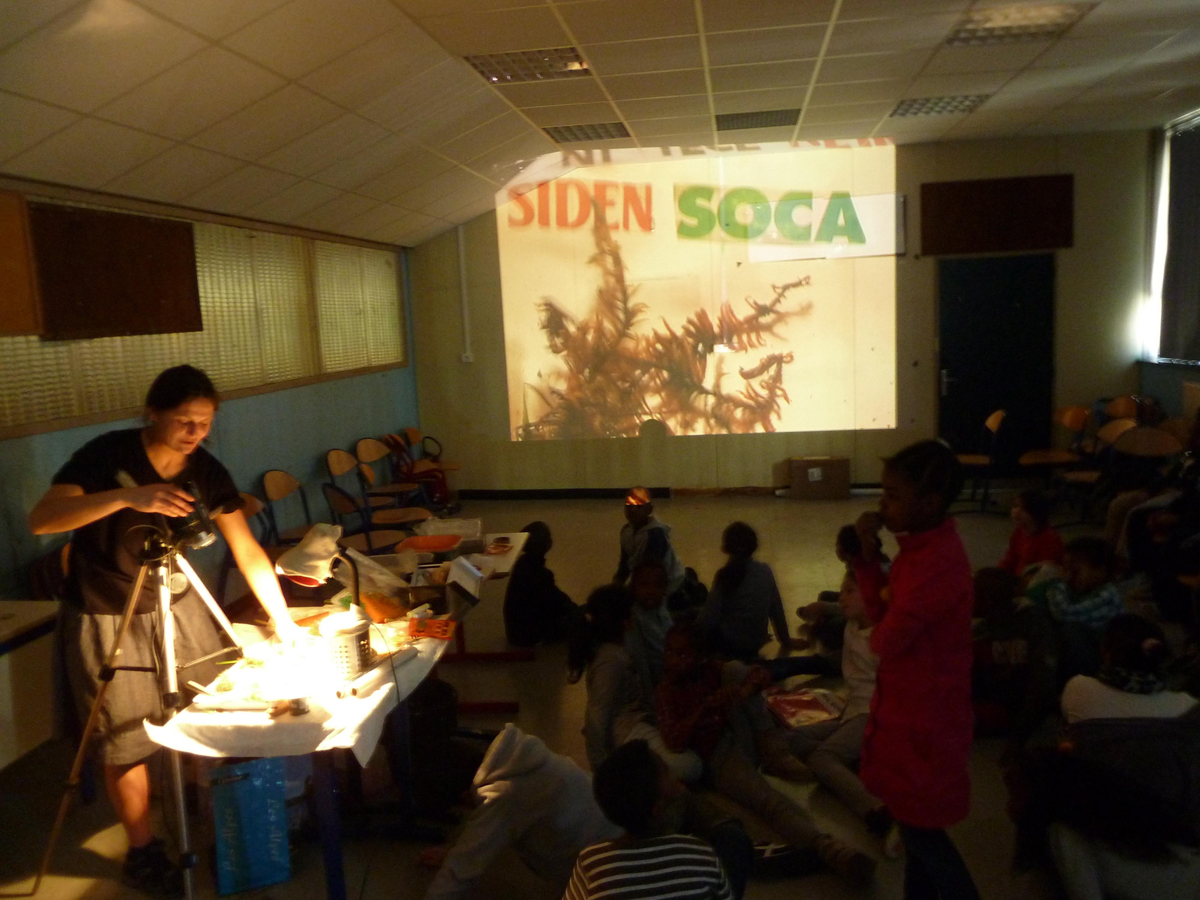

However, given the frustration that is often evoked during the interviews which relates to the impossibility of translating a dream into words, we also decided to include visual language so as to develop other forms of expression in which images help to bring out the memories. We called this the Oniroscope. It is a group meeting at which the group interacts with a visual creation performance. We invite people to share their dreams and, at the same time, participate in a filmmaking process. The participants are invited to participate in the Oniroscope with a dream and to bring along an object related to the dream. While the person recounts his or her dream to the group, Tuia works with and records the objects in real time. I ask questions about the dream by inviting the other participants to intervene with other questions or by comparing their memories and their perceptions with each other. I try to get the speaker to provide as much detail as possible (colours, landscape, sensations, textures, subjects involved etc.), which allows Tuia to adapt and transform the scenes and objects she films in line with the story as it is being told.

next...

Above: Oniroscope at the Night of the Archives, in collaboration with Manuel Salvat and Jérôme Gallician, Archives Départementales des Bouches du Rhône, December 2013.

6 Tuia’s use of video is based on an approach to forms, textures, and tactile sensations that is suggested by the real objects. She mixes and combines multiple ways of looking at objects and playing with their aspects (shape, colour, texture). While the Oniroscope is taking place, people can experience something real and concrete that nonetheless has an absurd dimension. They can have the perception of a very realistic situation and, then, suddenly witness the emergence of incongruities that run counter to reality. And yet, it is precisely the co-existence of these two planes that is often mentioned as a characteristic of the dream experience.

next...

Excerpts from Oniroscopes (3.5 min) of “A Kurdish dream” by Boris Bayard and Thomas Weber. Produced by SATIS (University of Aix-Marseille) in collaboration with the Kurdish community of Marseille. Excerpts from the Oniroscope at Francis' in Saint-Antoine, Marseille, June 2014

7 The Oniroscope is a temporary space for creation and a field of inquiry. Thanks to the contributions of very diverse groups of people, its modalities have developed and adapted according to the circumstances. With the support of non-profit networks, we have sometimes organised Oniroscopes by inviting people to a public place (social centre, kebab, theatre, archive etc.). In other cases, the group already existed: a school class, a group of people attending the same social centre, a group of minors in prison, a group of university researchers.

next...

Oniroscope at the elementary school of Parc Kallisté, as part of the Rêver la Méditerranée project, an anthropological and artistic research project in the northern districts of Marseille, IMéRA residence, 2013.

8 Tuia - At the end of the Oniroscope, I forget almost everything that has been said and the images that have come out of the performance. However, I record the whole session with my video recorder trained on the objects, coupled with an audio recorder. Then I edit the audio and the video together into a single document that helps us to keep track of the dreams that we are told in our shared archive. The nature and function of this archive will serve as a topic for a new article.

next...

Excerpt at Every Thursday,

Oniroscope at the Kallisté La Granière social centre, May 2013

V. Dreams and objects

9 “In reality, as soon as each hour of one’s life has died, it embodies itself in some material object, as do the souls of the dead in certain folk-stories, and hides there. There it remains captive, captive forever, unless we should happen on the object.”

(Marcel Proust, Against Sainte-Beuve)

Mementos and objects of affection (Dassié 2010) are not only apprehended according to their symbolic function or as representatives of facets of a pre-existing culture or identity. They are mediators that help to get closer to memory, feelings, and the sphere of the inner self. Like actors, they can forge links, produce thoughts or generate practices. While asking people to bring an object connected to their dream, we choose not to specify the nature of this connection. I observe the various possible associations between dreams and objects and how an object’s characteristics can trigger a narrative more in line with the content and the perceptions of a dream.

To better control – in real time – a story that is unspooling as people are looking on, I need to discover something along with them and it needs to be amazing. It is also important that the object be entrusted to me by the person telling the story. This is the concrete link between the person and me, the anchor that his or her dream can drop into the solid dimension of our meeting.

Several people have brought an object with them (phone, chocolate, soap, cigarette, cup, key etc.) that played a role in their dream. Others have chosen the object because of a smell, a flavour, or a colour that they perceived in the dream and that has remained etched in their mind. Such was the case of a student who brought a red scarf with her. She explained that the impression of intense red came from the outfit of a journalist who appeared on television in her dream. The smell of food left its mark on the memory of a dreamer in Saint-Antoine. She brought a packet of curry to the Oniroscope because in her dream she was cooking a large pot of couscous. Another dreamer brought with him a bell to help him describe a sound he had heard in his dream. Although most of the objects refer to visual perceptions, there are also other sensory elements that guide the choices of dreamer-participants.

Many objects have had no direct link with the content of the dream but had been given to the dreamer by the person in the dream. Often, from the story of how and why the object related to this person in the dream, the narrative branched out to the dreams’ consequences and influences: for example, when waking up after such dreams, several participants said they felt the need to contact people seen in a dream or experienced a kind of unease when meeting them during the daytime, as if (the memory of) the dream had affected their relationship in some way.

We have been presented with a variety of amulets used by the participants, including by those who claimed not to attach much importance to their dreams. Objects devoid of any link to a specific dream but regarded as sleep protectors... A stone, a bracelet...

We have also received drawings or artefacts inspired by dreams. For example, one girl had dreamt of a deer. After waking up, she carved a piece of olive wood to remind her of the animal’s antlers. Another dreamer sketched the strange space shuttle that had appeared to her in a dream the night before.

next...

Tuia Cherici, Cigarettes nightmare. Association of an object brought by a student, a pack of cigarettes, with an oil painting by Tuia Cherici. Screen capture extracted from the video made during the Oniroscope at Columbia University, New-York, within the framework of the doctoral seminar in anthropology of Pr. Michael Taussig, November 2015.

Tuia Cherici, Oniroscope at Materia Off, Parma, Italy, 2012.

Association of an object brought by a participant with a lens wetted with Betadine.

Screenshot extracted from the video made in real time by Tuia.

Oniroscope at the Circolo ARCI in Settignano, Florence, 2012. Photograph by Andras Calamandrei.

10 Tuia - "To do the Oniroscope, I prepare my set of objects by paying careful attention to the feelings, memories, fascination, symbolic power, texture, pleasure or fear that each small piece conveys to me when I am busy preparing the materials to bring along. In Italy, the method that women getting ready for their wedding have traditionally adopted is very much in line with the makeup of my toolkit: something old, something new, something from my family, gifts, things bought for the occasion, something very red, something from a distant land, something precious and something found."

During the Oniroscope, Tuia makes contact between the objects given by the dreamers, which she discovers at the same time as their story, and her own objects and tools. Every object that the participants bring with them can impose conditions (or constraints) of use on the artist.

Tuia - "An entire chapter could be dedicated to the status of a photograph chosen as the key object of a dream. While a photograph is an object whatever its format, it is often the subject depicted in it that one wishes to share. In other words, it is about making an image of an image... They bring many of them – especially young people: pictures on the screens of their phones, and I work on their phone and play with the saturation of the re-projected pixels, with the keys, with the Nokia whose screen turns off after 10 seconds on standby... I play with it just as much as I would with an old picture in a frame, whose damaged edges and moisture stains help me to place the person in the photograph into the dream as it unfolds."

By manipulating the objects, the artist creates a fiction that materialises instantaneous interpretive hypotheses about the contents of the dream as told. In this way, a parallel movement is created between the two narrative fictions: while the dreamer tries to reconstruct his or her memory of the dream and looks for the words to express it, Tuia listens to the narrative and looks for the right objects, materials, and tools and decides how they interact with each other. The other Oniroscope participants and I listen to the dreamer’s words, watch the video projection, and use our questions and remarks to interact with this double narrative.

next...

VI. Dream, story, fiction

11 “There are times when, upon awakening, we know we have seen the truth in our dreams with such palpable clarity as to satisfy us perfectly. (…) Once awake, however, even though we can still recall the dream images in all their sharpness, the script and the word have lost the power of truth. Sadly we fondle them, the spell gone, unable to glean their portentous significance. We do have the dream, but the essence is inexplicably lacking, buried in a land to which, wide awake, we no longer have entry.” (Giorgio Agamben, Idea of Prose, 1995)

People are often disappointed when they tell their dreams. Even when their recollection of the dream is vivid, there is a sense that some of the parts and details of the dream are disappearing and are then gone forever. Moreover, when we tell the dream to someone else, we have the feeling we are moving away from the richness of the dream experience. To be able to make himself/herself understood, the speaker feels obliged to tidy up an experience whose assortment of places, temporalities, sensations, and perceptions may constantly be layered on top of each other. Anthropology has long questioned the way in which telling a dream represents an act of communication – a performance influenced both by memory and by place, by time, by context, by the listeners, by linguistic structures and by the ways in which the dream is shared and used (Kilborne 1981, Perrin 1990, Tedlock 1992). Recounting a dream is never a neutral act and cannot be considered a genuine account of the dream experience. Thus, it represents a fiction in the etymological sense of the term: something that is made – a more or less faithful reproduction of the dream experience. It is impossible to measure the difference between the two from the outside.

In the Oniroscope, the fictional nature of the dream’s retelling is a starting point to which the artist adds a fiction created with objects and images. Although the dreamer is inevitably restrained by the limitations of language and memory, the Oniroscope makes it possible for the fragmentary and the incongruous to find their place and be expressed, while images and memories can be described without being absorbed into a story.

It is not about trying to understand what the meaning is of the images that appear in dreams but rather about getting as close as possible to the images themselves and to the perceptions and emotions they provoke. The purpose is to share collectively what the dreamer remembers while seeking out a common language to talk about it. The participants often say that interacting with the artistic practice makes them feel freer to talk about their dreams because they do not have to worry about keeping the narrative coherent, being judged by others or being the target of interpretations behind their back or “over their shoulder” (Geertz 1973).

It was also during the Oniroscopes that I became aware of how, in my previous research, I had apprehended dreams based on socio-cultural variables and local interpretive codes, while their phenomenological dimension remained in the background. I examined the substance of the dreams very seldom. Now, new questions arise: do you remember the dress your mother wore? Did you fall gently or suddenly? Was it day or night?

“It was night”, replied Dominique during an Oniroscope held in her class (Collège Mazenod, Marseille). Tuia switched off the small light that had illuminated her table with objects. The screen suddenly turned black, and a few seconds later, Tuia switched on a small LED torch. The atmosphere of the scene had completely changed. Even though Dominique had not mentioned this point in her narration, faced with the semi-darkness that had been created, she began to give a detailed description of the apprehension she had felt in her dream. Her voice took on a different role in the story, and with it, the atmosphere in the classroom changed; so, too, did the way in which the other participants were listening. The dreamer’s and the artist’s narratives proceed in parallel, following and influencing each other, while also stimulating the questions that the participants and I pose to the dreamer. Sometimes, watching the images at the Oniroscope, they are astonished to discover they are reliving fragments of the dream that they had forgotten but which reappear at that moment.

next...

12 Tuia - "I begin by just lighting up a neutral background, white or black. I wait for the person to enter the story of his or her dream. As the dreamer tells us the story, I begin to manipulate the object they entrusted to me, and then I’m ready for the “all of a sudden” moment of the story to come at any time. It almost always happens – sometimes even several times for the same dream.

The challenge for me, during each sequence that comes alive in my hands and under my eyes, is to make it possible for the frame that I am filming to transform, to disappear or to accommodate other elements when “all of a sudden”, in the dream, an event disrupts the initial setup.

I have to be ready without knowing what to expect. And the story consists of what the person says, with the fluctuations of their voice, their volume and their silence, as well as the reactions in the room, the interruptions by Arianna who asks for more detail, the behaviour of the objects that I have in my hands and the image that is created..."

next...

Forms (excerpt), Oniroscope at the Marie Curie high school, Marseille, March 2013

13There are also times when the video projection reminds someone else of a dream they had or when those in attendance identify connections with their own dream experiences.

“There were many times when I wanted to interrupt to say that it was similar to a dream I had had (…) I didn’t think others were dreaming the same as me. I thought it was only I who had them. (...) it looks like we have the same feelings about certain things” (Oniroscope, Lycée Marie Curie, Marseille).

“A certain atmosphere was reproduced that brought up something I had felt in my dream. When I was recounting it, I was almost as anxious as in my dream. Because I was telling it and seeing the atmosphere reproduced” (Oniroscope, Departmental Archive, Marseille).

“For some dreams, I really felt that if I was the one who had dreamt that, it would have been similar... I don’t know, it was weird” (Oniroscope, Saint-Antoine, Marseille).

Sometimes, it’s just an action carried out on the object: when one of the students, Jamie, saw Tuia’s hands projected on the screen breaking a bar of chocolate, she suddenly said she was reliving a sensation she had felt in her dream.

Tuia - "What matters is not the degree of similarity between the dreams and the images but rather the interaction between the two narratives. This interaction encourages the one who is telling to deconstruct the way the dream is told and to approach recollections in other ways – by utilising aspects and details that would otherwise be neglected.

Sometimes, I can’t even hear parts of the story, or I don’t understand the meaning of what has just been said. French is not my first language. In these cases, I focus on the movement of the voice as a melody to carry the action forward.

Arianna tells me it doesn’t matter, that, on the contrary, these misunderstandings allow the images and the story to intertwine in surprising ways. Nevertheless, to me, the capacity to listen and understand, and the capacity of the action to be conveyed by the imagination of the Other is what I use to learn.

This is not only so as to become more skilled in my improvisation techniques but also because I see the objects, actions, and people appearing around me, a way to explain and join together which is very beautiful and unusual. It is an intimate, peaceful, poetic exchange that helps us to grasp our differences and find ourselves in emotional demands beyond our cultures and contradictions. I view the collective practice of the Oniroscope as having the social (and political) goal of understanding others. It carries in it a critical reflection on the origins of the images in our minds.

The Oniroscope can also test general statements made about dreams, which are sometimes difficult to pin down in an interview. For example, to the statement that “In my dreams, the things I see are blurry”, Tuia responds by blurring the image that appears onscreen, using glazed panes of glass or the camera’s zoom function. Marc, the dreamer, responds: “No, not like that.” Trying to find a reason for why his definition of blurriness does not coincide with the image Tuia created, Marc explains that he actually sees the images quite clearly – he sees the details but not the outlines of things. Blurriness, in this case, refers not to a change in the sharpness of vision but to not being able to perceive the overall picture of a dream scene or situation."

next...

Tuia Cherici, Dream of Bougainville. Screenshot from a texture study of a dream. Photo printed, then wet and associated with a painting, Bougainville, Marseille, 2014.

14 For Sadia, by contrast, the blurred vision in her dream is more associated with the faces of the dead. Often, she manages to recognise a deceased person who comes to visit her in a dream, but she can’t see their face, which is “blurry”. Tuia takes a picture of a person and blurs their face with glazed glass layered on top of it. This act leads another woman to share a similar experience: she is also unable to see the face of a deceased person clearly. This topic came up on several occasions during Oniroscopes that were held in the northern suburbs of Marseille and generated discussions about the dead and how they are manifested in dreams.

next...

Excerpt from “Dream notes” (50 sec.) A documentary film by Tuia Cherici on “Collecting dreams in the northern suburbs of Marseille”, archive of interviews conducted by Arianna Cecconi, March 2013–June 2014

Tuia Cherici, Oniroscope in l'Estaque. Screenshot of a video. Oniroscope at the Estaque Social Centre with families from the Seon Basin and the city of La Castellane, Marseille, 2016

15The blurriness of dreams is not necessarily the same as in movies, when the image goes out of focus to signal to the viewer that a character is dreaming. The blurriness we refer to with the Oniroscope includes a wide variety of perspectives on a situation that, over time through exposure to the language of film, have been covered by this one expression. We have found many other examples of vocabulary borrowed from cinema and TV that, when we dig a little deeper, prove to be misleading when a dream that is told is turned into a concrete image.

“I saw my father in my dream…”, “all of a sudden, I was back home…”. Tuia starts to create images, and it often happens that the dreamers point out that the thing or the person in the dream are not exactly the way they are in waking life; and yet, they are certain of having dreamt of their father, their friend, their home.

“At that moment, I believed that my father had turned into a baby. I didn’t see him change, but in my head, there was a baby, and I knew it was my father. I was with a friend who had arrived (...) my friend went to the car, and I give my father to him. ‘Look after him’, I tell him, ‘make sure he is firmly fastened.’ There’s another baby, but I don’t know who it is. So, there are two babies in the car. My friend is in the back with the two babies. I go to sit in the front to drive, and I say, ‘I’m warning you, I don’t know how to drive,’ (...) and the moment I start the car, I wake up (Oniroscope, Lycée Marie Curie, Marseille).

While I was conducting interviews in various contexts, I could observe how, when a person recounts their dream, in order to keep the thread of the story, they don’t spend time pointing out the differences between how something or someone looks in the dream and how they do in the waking life. The verb “to see” is generally used to say what we perceive in a dream, even if “recognise” would often seem to be more appropriate, or “know that”, as evoked in the testimony of Michel above, who “saw” a baby in his dream but nonetheless “knew that” it was his father.

The Oniroscope invites those doing the telling to provide as much detail as possible in their descriptions of forms and appearances because the video image is created alongside them and based on their data. It is through this practical requirement that the discrepancy emerges between what we identify – or recognise – in a dream and the appearance it takes when it is manifested (how we see it). This encourages us to reflect on the process of ascribing meaning to a dream image and on the ability we have during our dream to recognise and name things, even when they do not correspond to the forms they take. In his treatise on photography, Roland Barthes, while talking about dreams he has of his mother, suggests this same ambiguity between the use of the words “to see” and “to know”.

"For I often dream about her (I dream only about her), but it is never quite my mother: sometimes, in the dream, there is something misplaced, something excessive: for example, something playful or casual – which she never was; or again I know it is she, but I do not see her features (but do we see, in dreams, or do we know?): I dream about her, I do not dream her" (Barthes 1982: 66).

There are many societies in which dreams are considered a form of specific knowledge, a form of knowledge that is not accessible to waking life and allows the hunter, for example, to know his prey or for someone to learn the identity of the person responsible for attacking him in his dreams in the form of an animal (Descola, Tedlock). Nevertheless, even in societies that do not confer such attributes upon dreams, dreamers get a first-hand experience of using their senses in a different way and of apprehending the world in other possible ways (feeling the thoughts of others, knowing things without knowing why or how we know them, communicating without speaking). It is difficult to share these types of experiences, which are often described with the same words or verbs (like the example of “to see”) that we use to talk about our perceptions and actions in our day-to-day lives. In this regard, one of the aims of the Oniroscope is to refine the language used to talk about dreams in order to highlight the specificities of the dream experience. Here, the effort of translating involves not only different languages but also using a language to refer both to day-to-day and dream experiences.

As Vincent Crapanzano points out, anthropologists have tended to limit their analysis to a dream’s symbolic meaning or the way in which it reflects cultural concerns. With the Oniroscope, following the suggestions of Binswanger and Foucault (1954), we seek to approach the dream as a mode of experience and a form of knowledge rather than a subject to be interpreted.

next...

VII. Some conclusions

16 The ambiguous boundary between dream and reality, or rather the fact of putting these two experiences on the same level, is what is characteristic of a primitive mentality, according to the first evolutionary anthropologists (Tylor, 1871). However, the problematisation of these two categories became a major element of the anthropological approach in the second half of the 20th century. From one language to another, the verb “to dream” can also refer to visionary or imaginative practices in a state of being awake, which are recognised as legitimate forms of knowledge that have an influence on “reality” (Perrin, 1990). The distinction between dreaming as an inner, subjective, experience and being awake as an objective experience relating to the “external” world – one that is the only collectively recognised form of reality – is the product of a specific socio-cultural context. It cannot easily be extended to other contexts (Crapanzano 1975).

"In Western cultures we place the dream within a person’s head. Many of the people who anthropologists study, however, see dreams as an alternative social world, as much outside the person as a convivial party, even if what goes on there is often far from convivial. (…) These people also locate the self in social role-playing rather than inside the person." (Mageo, 2003).

Most of the Oniroscopes have taken place in Europe and the United States with different groups, although they are often comprised of people who “place the dream within [their] head” and draw a clear line between dream and reality. However, this line (or border) is not easy to define, and among these exchanges of dream stories, some opinions regarding how and why the dream affects the dreamer suggest a kind of upheaval, an overlapping of real and dream experiences.

Below are a few examples of this scrambling of the borders:

Many of the dreamers recount dreams in which (often dead) people appear, even though they have departed from living reality. However, their appearance in a dream is so real that it affects the subject as if he/she had really been visited by the missing person. For some, these dreams managed to change their perception of the person by becoming part of how they remember the deceased.

Others mention people who and places that, although unknown and unreal, recur in their dreams, exert a strong influence on the dreamer and even raise doubts in them about their (non )existence: “Do these places or people really exist?”

Dreams associated in retrospect with an event that happens later, during the day, are surprisingly common. The event brings the memory of the dream flooding back, and the dream takes on the character of an anticipation of reality, even for those who do not believe in the premonitory power of dreams. Here, the dream seems to play the role of an anticipatory fiction.

next...

Excerpt from The Red Scarf (Le foulard rouge) (1 min). Oniroscope at Purchase College, New York, as part of the Media and Ethnography seminar led by Professor Kim David, November 2015

Excerpt from The Clock (L’Horloge) (3 min). Oniroscope at Columbia University, New York, as part of the PhD seminar in anthropology led by Professor Michael Taussig, November 2015

17 During the Oniroscope, people mention certain physical sensations and emotions that they experience as being so real and so intense that it is difficult for them to explain the difference between the emotion when it is caused by an event in a waking state and one in a dream. They subsequently recognise the extent to which the emotions produced by a dream can leave traces in and even influence daily life. Memories of dreams are also combined with other memories from the past, making some people question the very status of their recollection.

For Appadurai (1996), imagination indicates that subjectivity has a constituent character. Far from being an alternative to action, imagination is an integral part of it. If this is true of the imagination, understood as an activity carried out when awake, one can justifiably advance the hypothesis that it can be the same for dreams, which come in a state of being asleep and, therefore, not only include the social but also influence and transform it in return by participating in the construction of the real.

Barbara Tedlock (1987) applies the notion of “performativity”, which the anthropological literature has analysed in great depth, particularly in relation to language and ritual, to dreams. On the one hand, the performative power of dreams manifests itself in the actions of people when they are awake and follow or are inspired by the dream experience. In this respect, dreaming is an integral part of the process of constructing subjectivity and social reality. On the other hand, the performativity of dreams is also connected to the effect the telling of the dream has on the community. Sharing dreams and talking about them have an impact on social relations and make it possible to know others in another way (Wax, 2004: 86).

The experiences that we have accumulated during our research have confirmed the validity of this perspective and of considering dreams as an integral part of our reality. They shape and question us, they form a part of our culture that reflects collective imagination and social life, and they can expand and, as a result, transform our knowledge about the world. For these reasons, we deem it necessary to create more sharing spaces and opportunities for socialisation around our lives as sleepers. Bringing our dreams, our nightmares and, more generally, our sleep experiences out from behind closed doors to share them in a group, inside a community, can reinforce their links and enrich their identity.

Knowing and valuing the many different approaches to the night around us can also help us individually to work through the unresolved mysteries that dreams offer us, along with the fears that we have of letting go, of giving up and of sharing our nocturnal experiences in order to find more comfortable forms in which to experience sleep.

Finally, although our work has until now only focused on the awakened man (Ekirch 2005), we find it necessary to link our daytime biographies with our nocturnal biographies and to collect and document dreams as an integral part of social realities; this will help us to gain a better understanding.

next...

Bibliographie

18

Appadurai, Arjun, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996

Augé, Marc, La guerre des rêves: Exercices d’Ethno-Fiction. Paris, Editions du Seuil, 1997

Barthes, Roland, La chambre claire: Note sur la photographie. Paris, Gallimard Seuil, 1980

Bastide R , Le rêve, la transe et la folie. Paris, Flammarion, 1972

Cecconi, Arianna, "Lieux où l’on dort, lieux des rêves : un regard ethnographique sur la nuit dans un cité des quartiers nord de Marseille". Article soumis à Ethnographie.org, 2017

Cecconi, Arianna, "Pratiquer ses rêves : Rêves, divinités et pratiques sociales dans les Andes Péruviennes" in L’autre, Cliniques, Cultures et Sociétés, numéro « Matières des rêves » (vol. 15 ; n°3), pp 274-282, 2015

Charuty, Giordana, Destins anthropologiques du rêve. In Terrain, 1996, pp. 5-18, 1996

Crapanzano, Vincent, "Saints, Jnun, and Dreams: an Essay in Maroccan Ethnopsychology" In Psychiatry (38), pp. 145-159, 1975

Crapanzano, Vincent, "Concluding reflections", in Mageo, Jeannette (ed), Dreaming and the self: new perspectives on subjectivity, identity and emotion, Albany, State University of New Yory Press, 2003

Dassié, Véronique, Objets d’affection. Une ethnologie de l’intime. Paris, Éditions du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques, 2010

Descola, Philippe, Les lances du crépuscule. Paris, Plonn coll. Terre Humaine, 1993

Descola, Philippe, Par -delà nature et culture. Paris, Gallimard, 2005

Duvignaud, Françoise et Duvignaud, Jean-Pierre, La banque des rêves. Essai d'anthropologie du rêveur contemporain. Paris, Payot, 1979

Elias Norbert, La civilisation des mœurs. Paris, Calamann-Levy, 1973

Foucault Michel, Introduction, in Binswanger, Le Rêve et l’Existence. Paris, Desclée de Brouwer, 1954

Geertz, Clifford, L’anthropologie Intérprétative. Paris: Gallimard, 1973

Kilborne, Benjamin, Interprétations de rêve au Maroc. Paris, La Pensée Sauvage, 1978

Mageo, Jeannette Marie ed., Dreaming and the self: new perspectives on subjectivity, identity and emotion. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2003

Perrin, Michel, Les Praticiens du rêve, un exemple de chamanisme. Paris : Presses Universitaire de France, 1992

Tedlock, Barbara ed. Dreaming: Anthropological and Psychological Interpretations. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987

Tisseron, Serge, Comment l’esprit vient aux objets. Paris, Éditions Aubier, 1999

> Back to the top of the article