antiAtlas Journal #4, 2020

Remapping the Neighborhood

Karen O’Rourke

Abstract: In Houston’s Third Ward, residents join with artists and architects to revitalize a historic African-American neighborhood. What can their maps tell us?

Biography: Karen O’Rourke is an artist and writer, emeritus professor at the University of Saint-Etienne. She is the author of Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers (MIT Press, 2013) and a co-founder of La Fin des cartes?

Keywords: art as remapping, database mapping, urban redevelopment, architecture.

Fig.27. MF Problem, Mobile Block Party flyer (2011).

To quote this article : O'Rourke, Karen, "Remapping the neighborhood" published on July, 10th, 2020, antiAtlas #4 | 2020, online, URL : www.antiatlas.net/04-remapping-the-neighborhood, last consultation on Date

I. Neighborhood Dynamics

Fig. 01. Project Row Houses: the original shotgun houses. The houses on this block are rented to young mothers. Left: the Holman Street view. Right: The shared backyard. Photo: Rice Building Workshop, Live/Work, 2006:38.

1 Back in 1992 when artist Rick Lowe saw potential in the twenty-two rundown houses on Holman street, his builder friends told him they weren’t worth restoring. Better tear them down and rebuild. But he had in mind the shotgun houses that structure John Biggers’s paintings of African-American communities. Mobilizing volunteers from all over Houston to renovate the houses as spaces for art and housing for young mothers, Project Row Houses opened in 1994.

In its heyday, Dowling Street was a thriving business district with grocers and dressmakers, restaurants and repair shops, barbers and doctors, a lumber yard and a printer’s. People came from all over to hear Milton Larkin, T-Bone Walker, and Joe “Guitar” Hughes play at the Eldorado Ballroom, “Home of Happy Feet.” In the 1960s and 1970s, population loss and disinvestment began to undermine that prosperity. “Dowling Street was like a small town within Houston,” notes photographer Earlie Hudnall, Jr, “and you know what has happened to small towns in America. Most of them have died”. Desegregation saw wealthier black families leave for the newly integrated suburbs. Businesses shuttered. Houses were torn down and longtime residents evicted to make way for two major expressways that cut through the neighborhood fabric. Other homes fell into disrepair and owners could not get loans to fix them up. Absentee landlords neglected their properties. Taxes went unpaid. By the 1990s, the neighborhood was in bad shape.

next...

Fig.02. Left: Third Ward townhomes. Photo: K. O’R., 2018. Right: One of six historic houses torn down on April 2, 2020, this single-family two-story home was built around 1930. Photo: Ed Pettitt.

2 Yet when Lowe and his friends began cleaning up the houses on Holman Street, the neighbors eyed them warily. What were the real motives of these young people in dreadlocks and spiked blonde hair “coming to rebuild, to paint, to restore decaying porches”?

Would long-time renters be displaced by rapacious developers, like the African Americans pushed out of downtown Houston?

The presence of artists in a run-down neighborhood often smooths the way for its gentrification. They reassure affluent home-buyers whose investments bring steep increases in land values, property taxes and rents.

next...

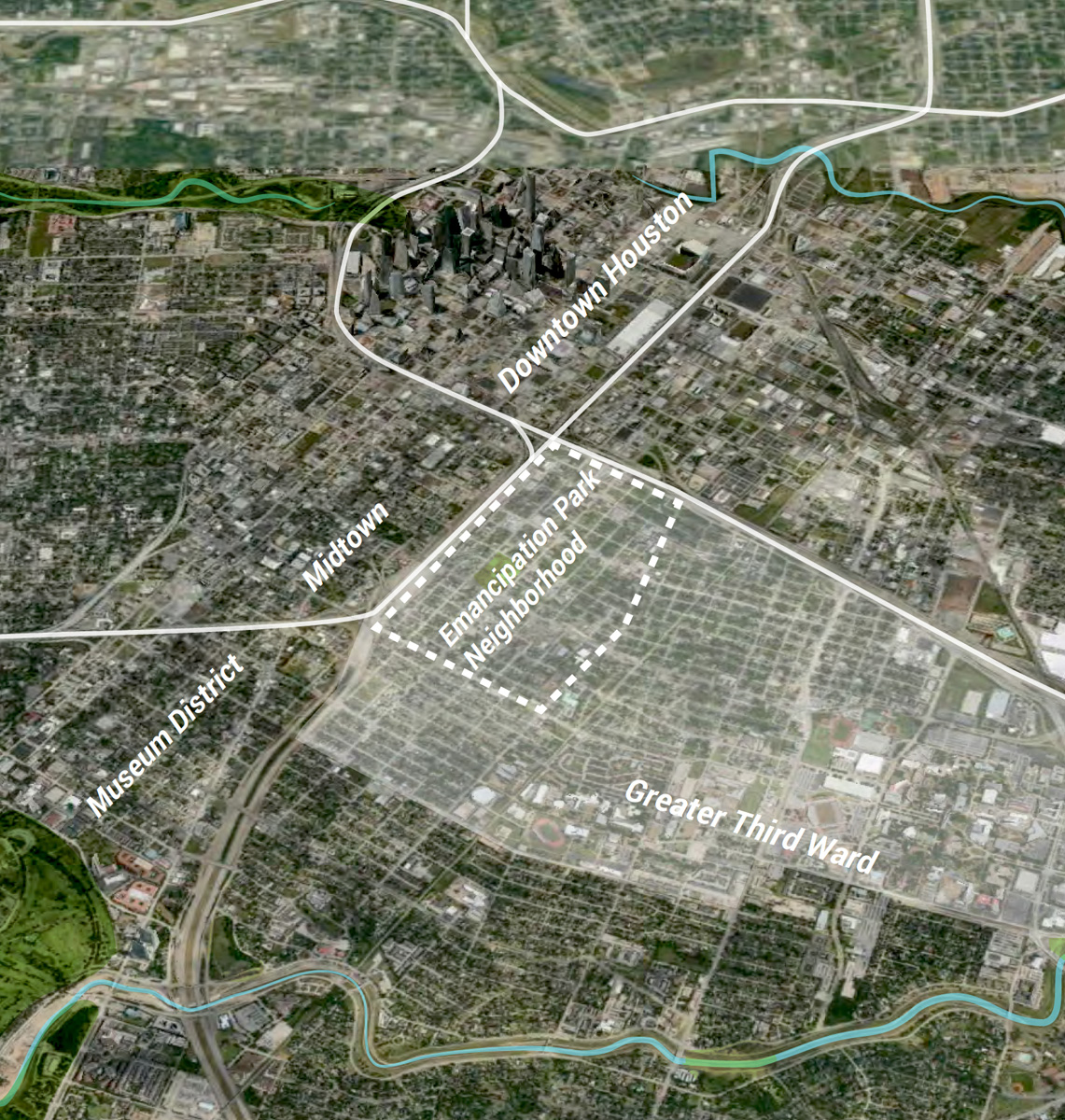

Fig.03. The Row House District, Houston. These maps show the 35-block area within Houston (left) and the Northern Third Ward (right). Maps: Rice Building Workshop, Live/ Work, 2006: 41-42

3 As prices in other parts of Houston rose, developers moved in on Third Ward, buying old houses and tearing them down to build luxury townhomes. The absence of zoning in Houston makes it all the more attractive to this new construction billed as “green-friendly.” Blocks of three and four-story dwellings built above garages do make more efficient use of land than single-family split-levels sprawling on spacious lawns. They also reap more profit for developers. The moving vans bring in creative-class migrants from suburbia - young professionals and empty-nesters eager to reduce commuting time and enjoy urban amenities. Third Ward is less than ten minutes by car from Downtown, and closer still to Midtown and the Museum District. Like fortresses in hostile territory, the new settlements stand aloof from the surrounding neighborhood.

next...

II. “Doing” and “To-Do” Maps

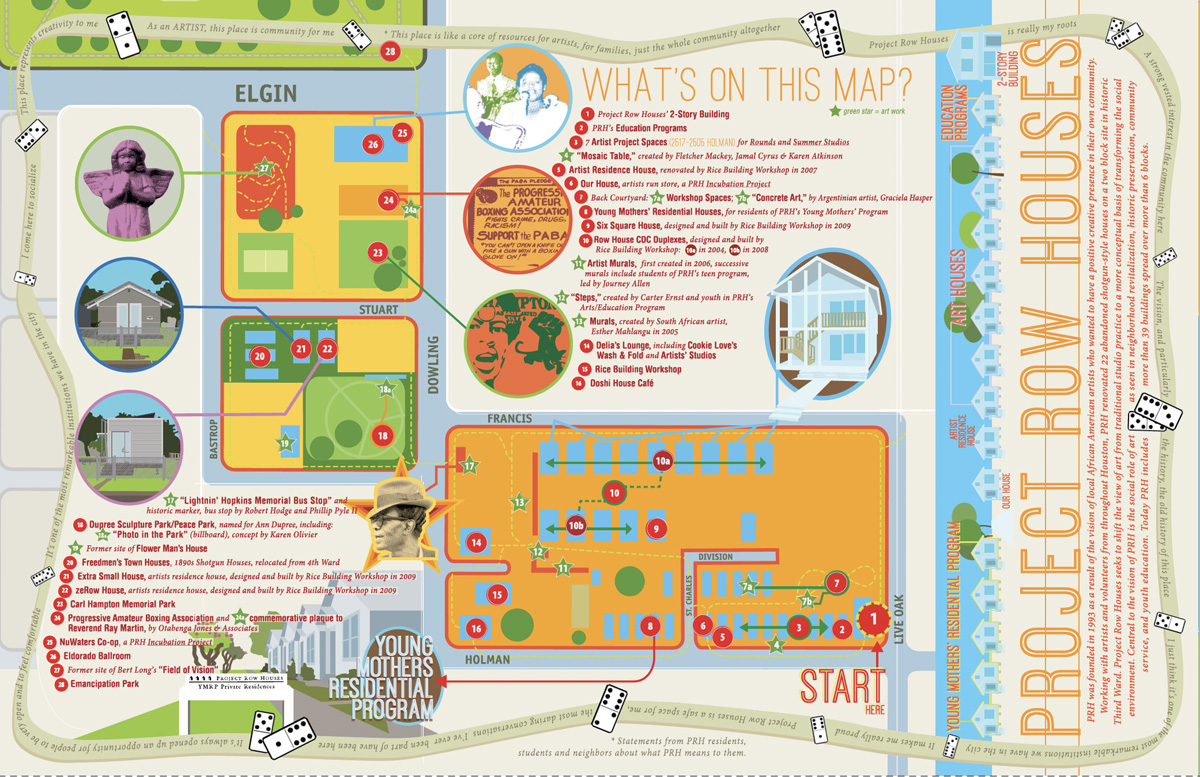

4 Project Row Houses began mapping the neighborhood at the outset. A visit to the archives, online research and conversations with key participants have netted two kinds of maps: “doing” maps (praxis) and “(re)framing” maps (aisthêsis). The former are instrumental maps made by people who plan to build in the area, or who develop strategies for revitalizing it, while the latter are symbolic objects, artworks. They shape reality by shaping the way we view it.

Many of the “doing maps” were made by architects.

Mapping is a way for them to study the site they plan to build on

Mapping is a way for them to study the site they plan to build on, its surroundings and infrastructure. It allows them to identify assets or drawbacks, and to present their projects to city authorities, clients, funders, builders.

next...

Project Row Houses Plans and Models

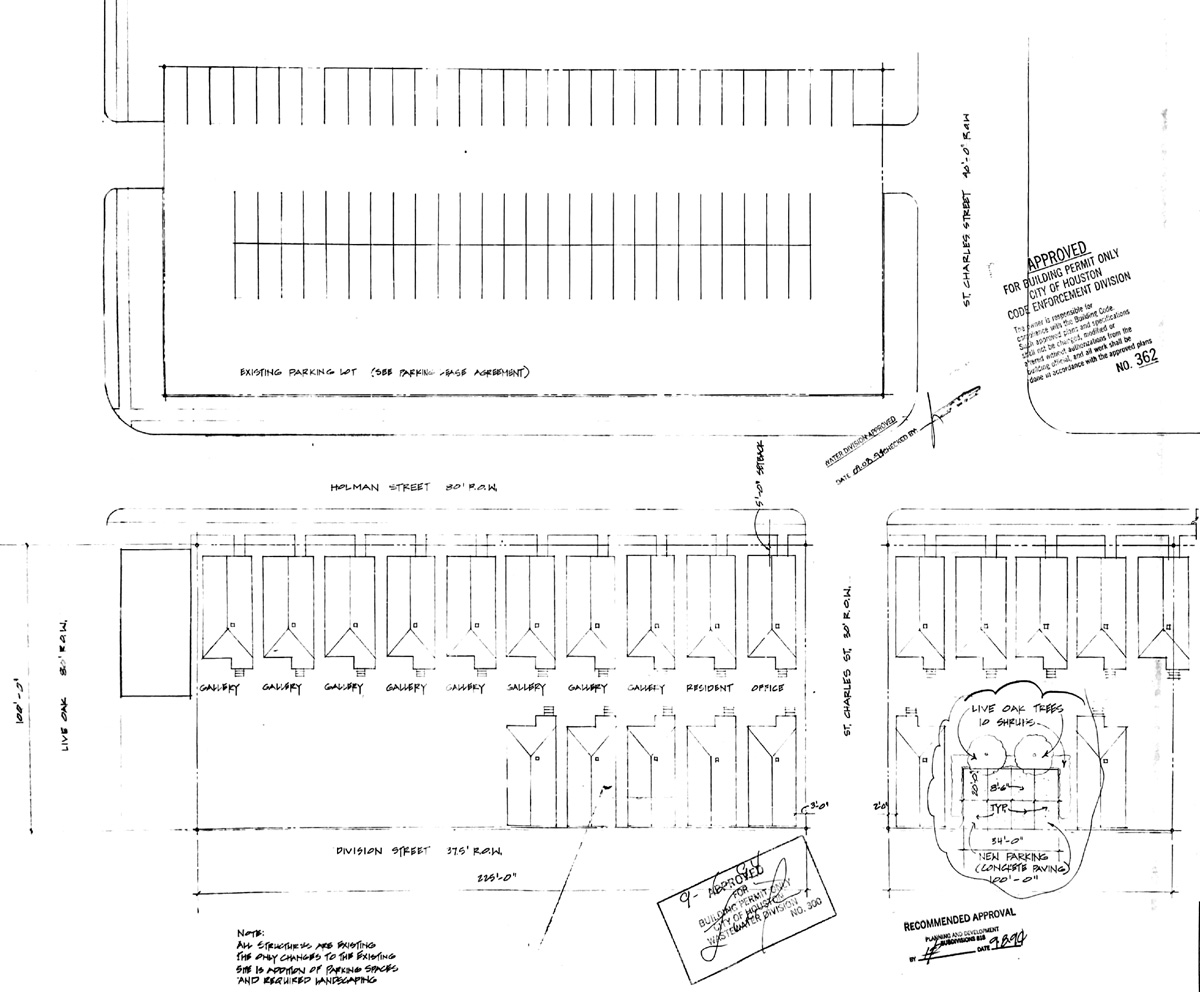

5 Architect Sheryl Tucker de Vazquez drew the first plans to obtain building permits and initial funding. She investigated the origins of the site, and argued for its historical significance.

The shotgun is a narrow, rectangular one-story dwelling built on concrete block footings. It consists of aligned front and back doors, and between them, three to five successive rooms. Folklorist John Michael Vlach traces the form to West Africa – specifically the Yoruba togun (house). After coming to the New World on slave ships, it was adopted across the southern U.S. It is well-adapted to unstable terrains, often near waterways; the cross-ventilation provides natural air-conditioning in sultry climates. The Holman street houses are a modified form of shotgun built in the late 1930s. Although they don’t share walls, they are small and stand close together (only three feet apart). Behind them is a common backyard where children once played and women hung their washing. In the evenings people sat out on the porches – “talking places,” as John Biggers called them. Around mid-century, shotgun houses began to lose their appeal (they lacked central plumbing) and gradually became a marker of poverty. This is when Dr. Biggers began painting them –to rehabilitate them as an African-American cultural heritage.

next...

Fig.04. Sheryl Tucker de Vazquez, Drawing for building permit, 1994.

6 The drawings suggest that the original development contained thirty identical small houses, half of them facing Holman Street and the other half facing Division Street. Between the two rows ran the narrow backyard. One map indicates which houses would serve as galleries, residences and offices for the new organization and includes one element of the surrounding neighborhood, the parking lot across the street.

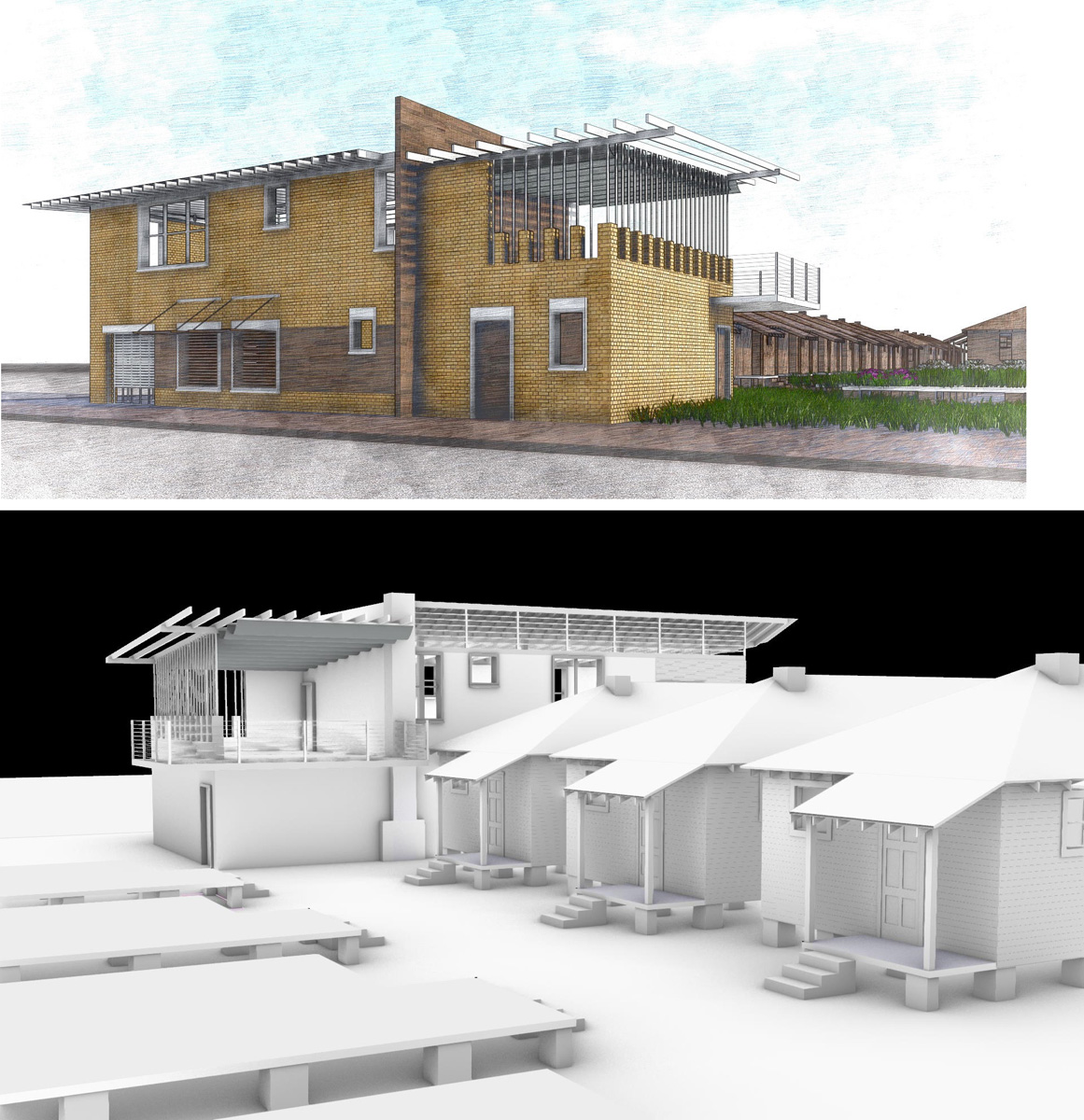

De Vazquez and her students at the University of Houston built models of the main site and imagined interventions to replace five of the missing houses. In 1995 she was awarded a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to re-design the corner two-story building. Her plan defines “a flexible indoor/outdoor gathering place” with a kitchen, a restroom and a small vegetable garden. It reflects her vision of African-American culture as based on reshaping the old and familiar, incorporating skylight windows and a lattice-screened balcony to open up the original brick structure to its surroundings. She received an A.C.S.A. award for the completed design, but was unable to raise the money to build it.

next...

Fig.05. Sheryl Tucker de Vazquez, PRH two-story, 3D renderings of the prospective re-design, 1995/2019.

On the right, Fig.06. Six Square House (1997-1999) was Rice Building Workshop’s first prototype for PRH. Top left: plan. Middle: assembling the panels. Right: The completed house in 1999. Bottom: axonometric drawings show the modular construction. Images: RBW/Construct website and Live/Work, 2006:58,60,61.

7 After founding the nonprofit and setting up its core programs –biannual exhibitions in the art houses (“The Rounds” 1994), after-school workshops for neighborhood children (1995) and the Young Mothers Residential Program (1996) - Project Row Houses turned to what Rick Lowe calls “real-estate speculation.” “We realized we were a real estate entity,” he says, “and there was other real estate around us”. “PRH started to purchase more properties round town,” recalls former gallery director Shy Morris. “Rick and I would go around to the neighbors, knock on doors to educate the community about what was happening with developers coming to buy their properties.”

“We realized we were a real estate entity,” he says, “and there was other real estate around us.”

Rick Lowe reached out to the founders of the Rice Building Workshop at Rice University. Architects and Professors Danny Samuels and Nonya Grenader started Rice Building Workshop in 1996 to give their students hands-on experience in building for the community. Working with nonprofit clients, the students “engage all facets of the architectural process, from conception through construction, allowing the act of making to inform every aspect of design”. In the Bauhaus tradition, the program emphasizes collaboration: students work closely with clients, consultants, contractors, suppliers, and craftspeople. “We had a very modest budget ($5k/year) from the School of Architecture, mostly for supplies and tools,” notes Danny Samuels. “Generally, the projects that we built with students were supported by grants that we applied for, and we had to be very creative about how we spent the limited funds”.

Working with nonprofit clients, the students “engage all facets of the architectural process, from conception through construction, allowing the act of making to inform every aspect of design.”

After Lowe invited them to design a low-cost house for the PRH campus, it took three years, and more than sixty Rice students, to complete the “Six Square House,” a two-story 900-square-foot structure inspired by the original row-house architecture. The modular side and floor panels were built on the Rice campus and assembled at the construction site.

next...

Row House Community Development Corporation

8 Their design/build projects produced compelling prototypes. The next challenge was to increase the number of housing units available for rent. When PRH purchased land adjacent to the Six-Square House, they asked the Rice workshop to draw up plans for a structure that could be built by professional contractors. The students designed a duplex superposing two two-bedroom apartments with large porches, and an outside staircase connecting them. But construction had to wait five years while the nonprofit secured funding.

In 2003, Project Row Houses and Rice Building Workshop founded the Row House Community Development Corporation to construct affordable housing in Third Ward. The next year, they received funds from the City of Houston to build four duplexes on Division street. The houses repeat the clean lines and relative positions of the original shotguns with gabled roofs overhanging the porches, yet they wear their structure on the outside in a harmonious, De Stijl-like composition of white pillars and crossbeams.

next...

Fig.07. The Division street duplexes (2004). Left: apartment floor-plan and photo courtesy RBW/Construct. Right: photo Rick Lowe.

9 Row House CDC then acquired the land just behind them on Francis Street to erect eight new “Hannah” duplexes with federal funding (2008), before teaming up with Midtown Redevelopment Authority to build the “Anita” (2010) and “Napoleon” (2013) duplexes in eastern Third Ward. To date, Row House CDC has built 54 two and three-bedroom apartments using Rice designs.

In 2018, Project Row Houses launched a new initiative to enhance existing housing in northern Third Ward. PRH Preservation, Inc. buys, refurbishes and manages rental properties “to ensure long-term, safe, and affordable housing for its residents". A grant from the Kinder Foundation allowed it to purchase and rehabilitate twenty-one wood-frame structures built between 1930 and 1950, without raising rents.

next...

Fig.08. PRH Preservation, Inc. Left: A model of the homes rehabilitated in 2018-2019. Right: These two-family houses were among the nineteen modified shotguns. Photos: K. O’R., 2019.

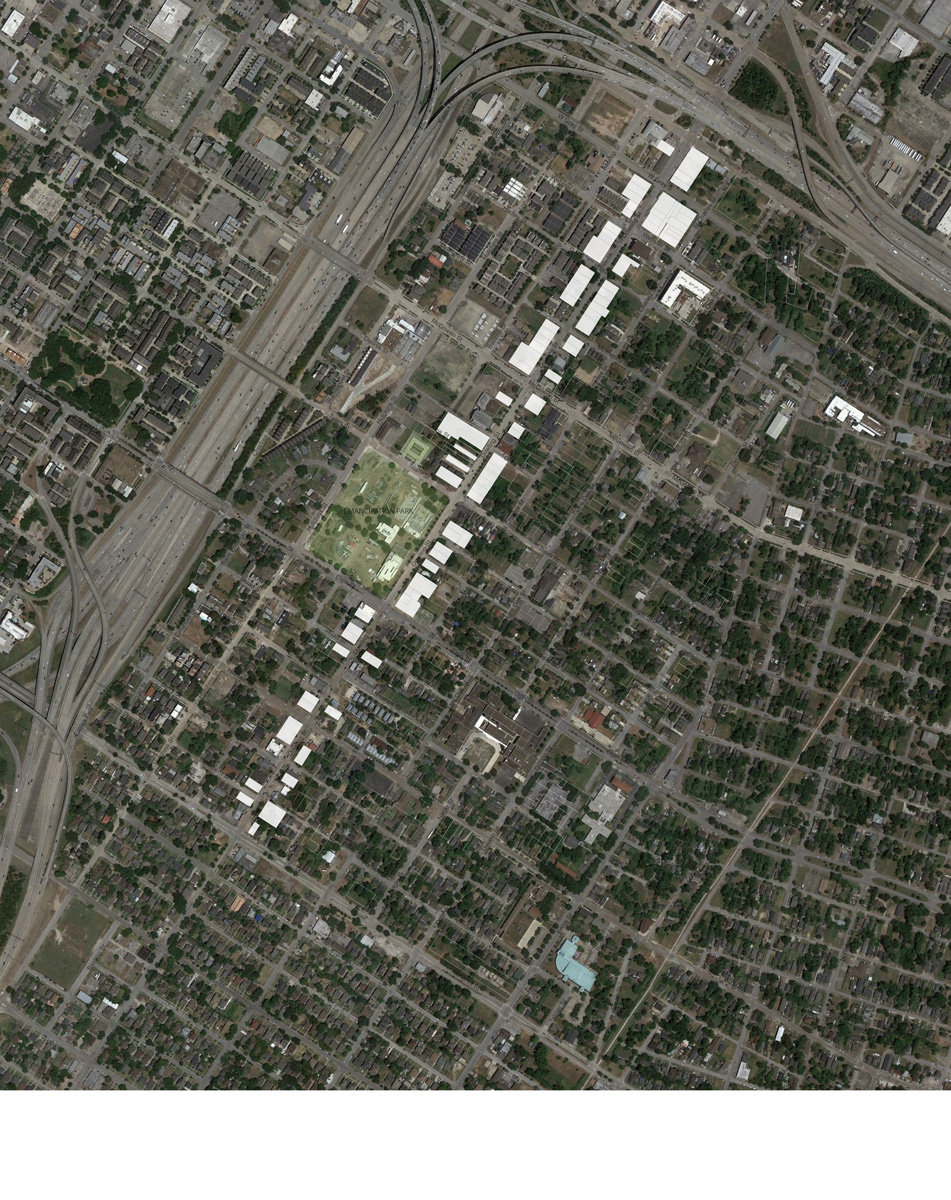

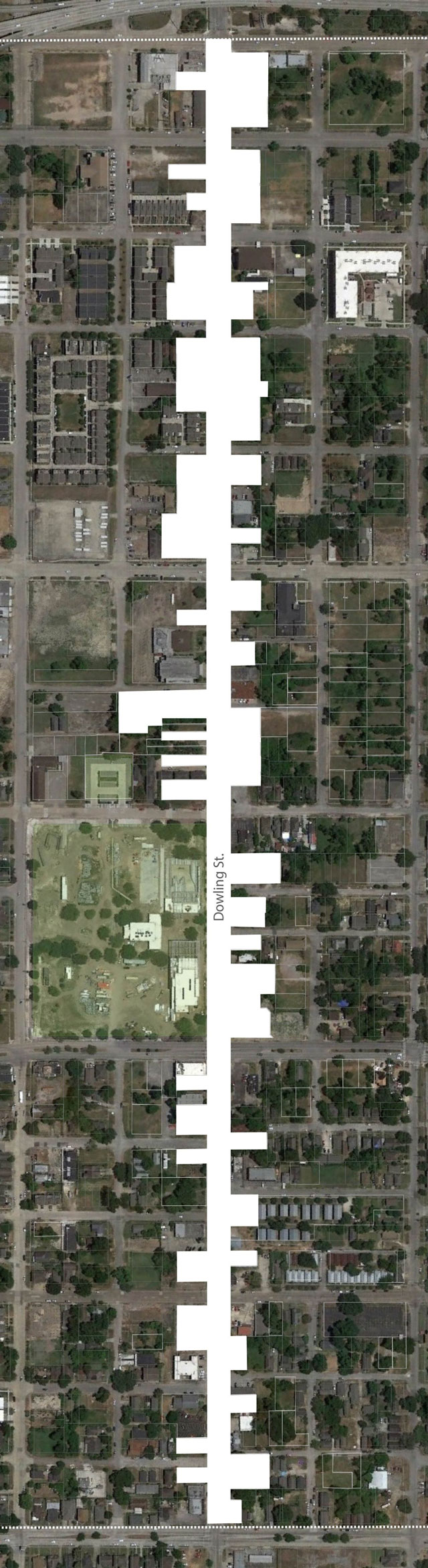

Every Building on Dowling Street Emancipation Avenue

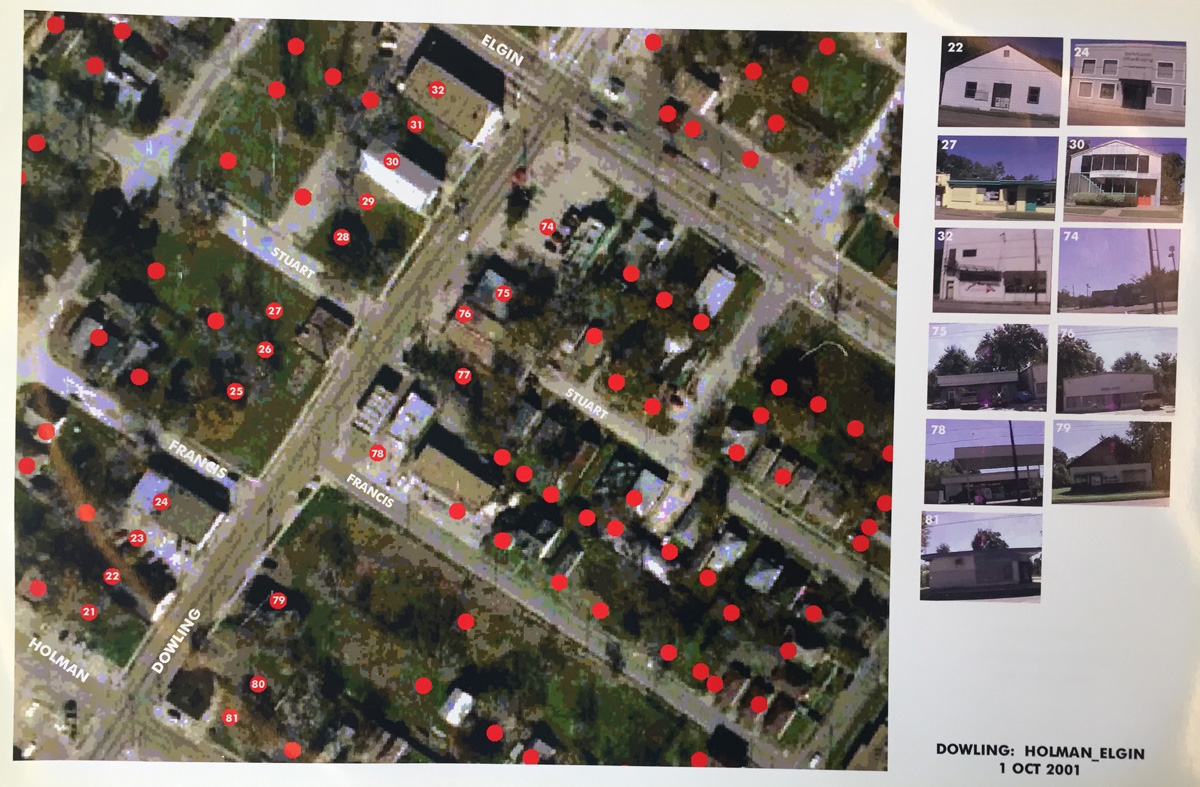

Fig.09. Dowling: Holman_Elgin, unsigned aerial view, 2001. Computer printout 11x16 in. Courtesy PRH Archives.

10 While these drawings and models focus on the houses themselves, Rice Building Workshop (now Construct) also collaborated with PRH on wide-area neighborhood planning projects.

One set of maps from 2001 surveys the neighborhood using enlarged sections of an aerial view. The maps show six swathes of Dowling Street (since renamed Emancipation Avenue) crossing at an oblique angle. Each one bears the date and a title identifying the two cross streets. They were made by digitally modifying the image, overlaying street names and placing in the right column numbered street-level snapshots of individual properties. Red dots locate these lots on the map.

next...

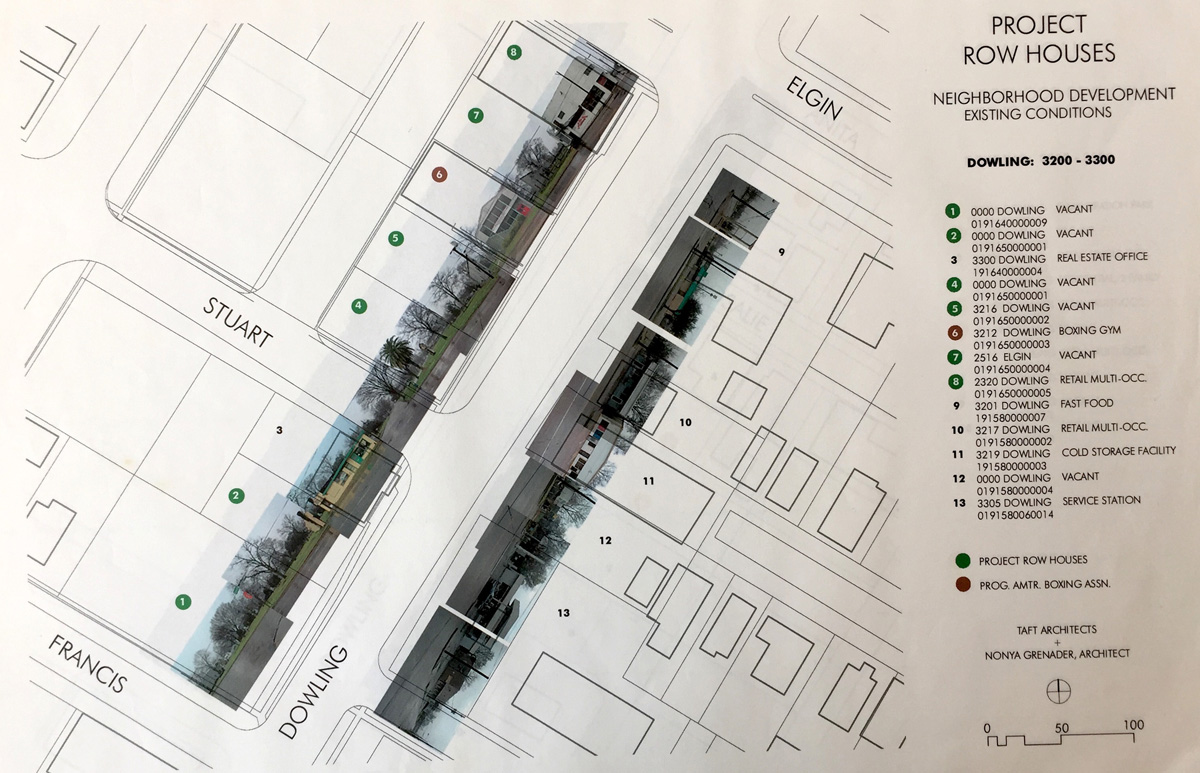

Fig.10. below: Taft Architects - Nonya Grenader, “Project Row Houses. Neighborhood Development Existing Conditions,” undated. Computer printout 11x16 in. Courtesy PRH Archives.

11 Another set of five maps bears the title “Project Row Houses. Neighborhood Development Existing Conditions.” These drawings show Dowling Street at a larger scale (1 in./100 ft). Like the previous series, the maps are identified by block; here, Dowling 3200-3300 - between Francis and Elgin Streets. They were made by University of Houston graduate student, Polly Ledvina: “Polly did a windshield survey of each building of each street face of each block,” notes Danny Samuels. She placed the photos side by side on a linear street map to form a continuous panorama along Dowling Street, superposing the perpendicular street-level perspective of the properties onto the bird’s-eye view. The lots are numbered and identified in the legend; when they contain a real estate office, a cold storage facility or a service station, it appears in the drawing.

The large green patches of vacant land on both maps show the neighborhood to be sparsely populated. Even today on the ground, it looks surprisingly rural for an area so close to the center of the fourth largest U.S. city. Of these maps, Samuels writes “the big challenge in planning is to find the suitable graphic techniques to represent information. In the photo-montages, with graphic techniques inspired by Ruscha and Hockney (did we have Photoshop then?), we were trying to show the surface characteristics of the street fronts. However, because the fabric was so low-density, and further depleted by removal, what we ended up showing was its very open nature. Polly’s background was in biosciences, so she approached this very empirically. My thing is trying to get the right mapping colors, and I think these land-use drawings are some of the best we have done".

Projects first imagined in the early 2000s may be built decades later.

Rice has developed an ongoing relationship with PRH. Long-term planning means that projects first imagined in the early 2000s may be built decades later. For an Eldorado Site Development study (2001), students proposed an African-American archive and exhibition space on Dowling Street. In 2018-2019, Row House CDC was again envisaging a PRH Gallery on what is now Emancipation Avenue. An overall redevelopment plan “to add housing and mixed-use to all available empty sites on the main campus”, includes retail incubation spaces on Emancipation and Holman Street - sorely-needed businesses that will probably employ local residents. Here, community groupings of two duplexes and two extra-small houses (based on a 2003 prototype XS House) share a common outdoor space.

next...

Fig.11. A Row House CDC Planning Study with PRH Gallery and new housing, 2018. Courtesy Taft Architects.

III. Learning from Third Ward: Database Cartography

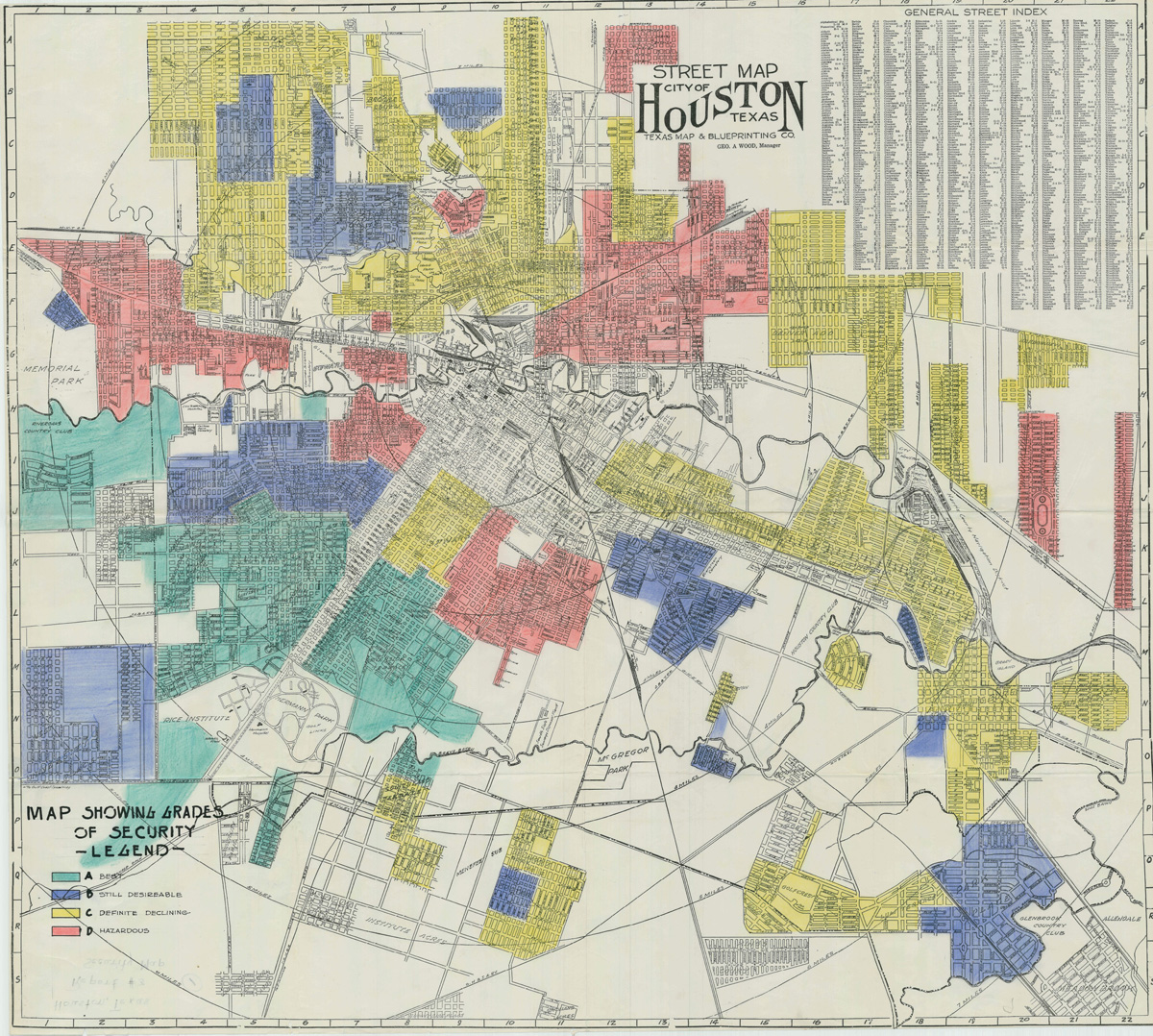

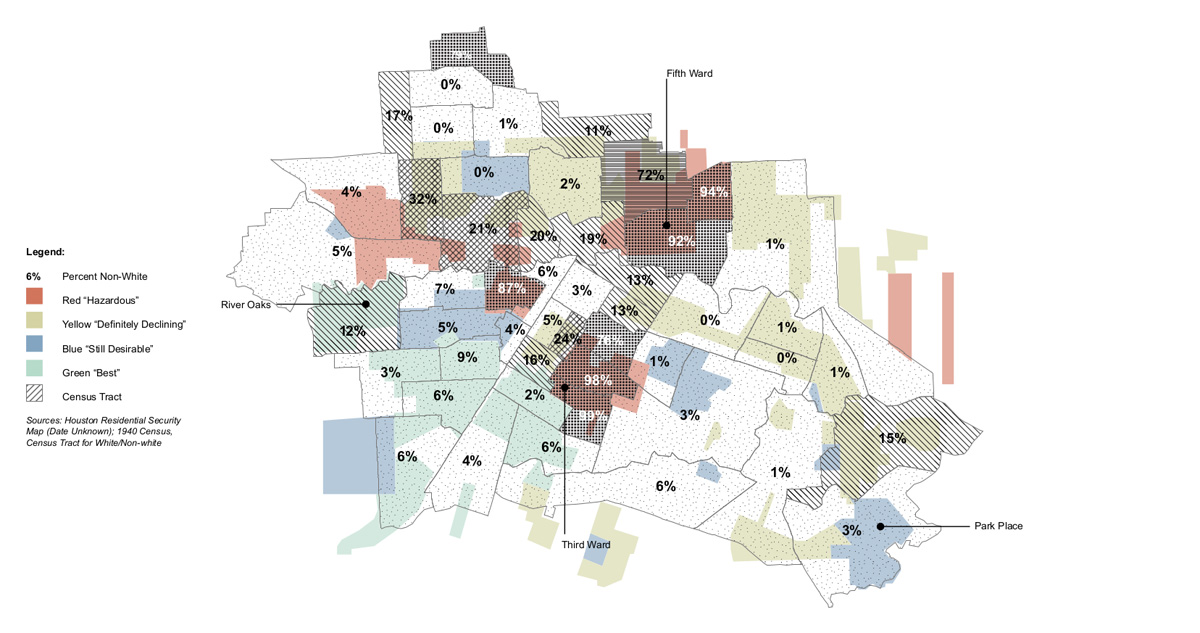

12 By giving statistics visual form, data-driven maps reveal a wide array of characteristics shaping the neighborhood. They offer interdisciplinary teams ways of pooling information and techniques to visualize the results. Planners can fine-tune projections, bringing together detailed information from a household survey and comprehensive coverage from a national census. Combining information culled from various sources enables researchers to analyze patterns of development over time and see larger trends at work. A recent interactive map made by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition superposes current demographic and income data on Home Owners' Loan Corporation maps from the 1930s. The HOLC maps that rated the “residential security” of each neighborhood are notorious for having provided banks with a reason to refuse loans to residents of areas labeled “hazardous.” The cities they surveyed show a strong correlation between “hazardous” areas marked in red and neighborhoods undergoing gentrification today.

By layering the HOLC map of Houston with 1940s census data on race, Susan Rogers reveals that a big chunk of Third Ward identified as 98% “non-white” was also labelled “hazardous.” She writes “The power of the maps was to make discriminatory practices visible and provide a verb for the practice of denying loans to certain areas of our cities — an act we now know as ‘redlining’".

next...

Fig.12. Houston HOLC street map. Texas Map & Blueprint Co. Street Map, City of Houston, Texas, circa 1930.

Fig.13. Houston HOLC map layered with 1940s census data on race. Courtesy Susan Rogers.

The Row House District

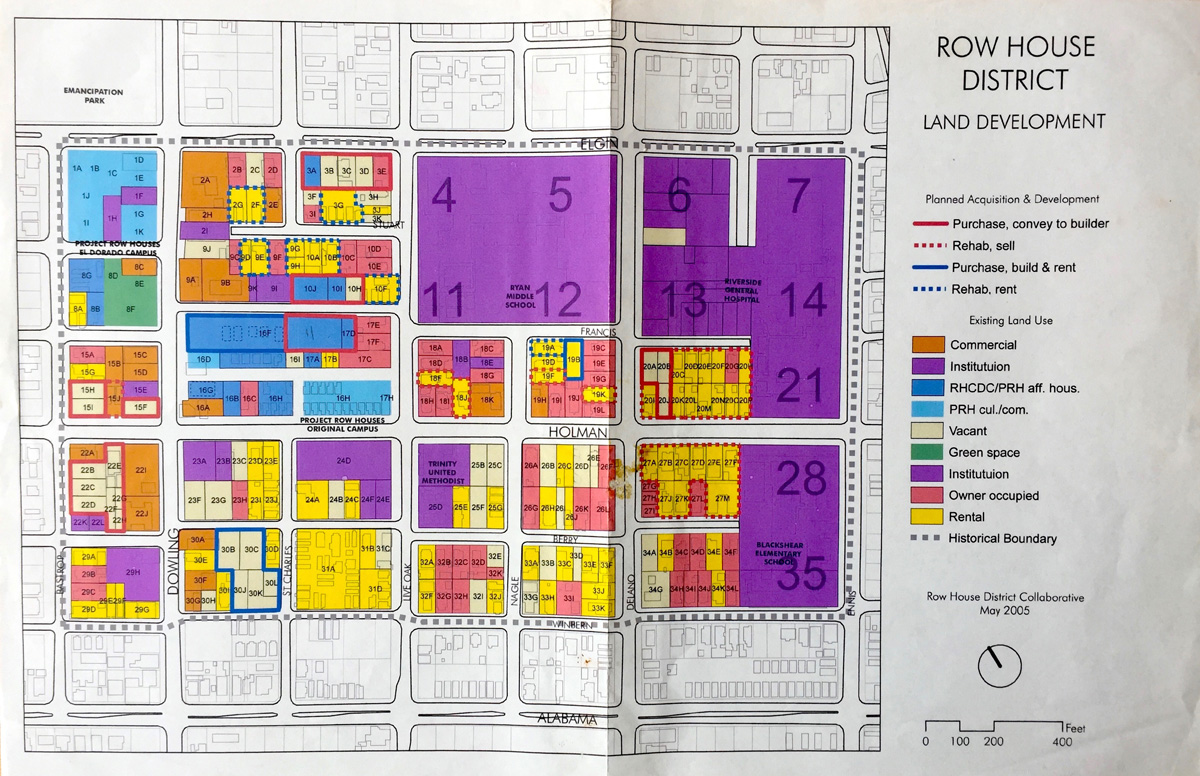

Fig.14. “Row House District Land Development” (May 2005). 11x16 inch computer printout. Courtesy PRH Archives.

13 The rectilinear “Row House District Land Development” map covers a thirty-five-block area in northern Third Ward. Part of a land-use plan drafted by a group called The Row House District Collaborative, it shows that PRH’s vision of the neighborhood has grown, and along with it, its ambitions. For Deborah Grotfeldt, the founding director of Row House CDC, the area was small enough for them to monitor its development. They had a fund for purchase, and were looking for adjacent properties. A spreadsheet from the archives bears information from public tax records on each property, including size, value, tax status and existing use. Identifying property owners and occupants (institution, owner, renter) gave the organization an overall view of the neighborhood structure. The group included a retired real-estate developer “and the task was to identify parcels that could be aggregated for development by developers, according to certain guidelines”. They prepared a report, but “but mostly it did not go anywhere”. If it had been successful, it would have allowed them to scale up their operations.

PRH’s vision of the neighborhood has grown, and along with it, its ambitions.

At the time, the City of Houston was looking to increase tax revenue to cope with the fallout from decades of neglect and reduced federal funding. Beginning in the 1970s, cities all over the country embraced gentrification as a solution for revitalizing urban cores. With its low level of citizen organization, Houston seemed to offer no viable alternative. Planners ostensibly adopted a policy of minimal state intervention and used tax dollars to attract investors. “Thus, despite the local laissez-faire rhetoric,” writes Igor Vojnovic, “government intervention in Houston's growth has been vital and has produced the extraordinary impacts usually expected from public involvement in local economic development”.

The City of Houston’s Third Ward Urban Redevelopment Plan (LARA, April 2005) opens with a map of tax-delinquent properties. It aims to increase affordable housing opportunities, while “returning abandoned property to tax revenue producing land”. The Land Assemblage Redevelopment Authority (LARA) was started in 1999 to acquire vacant, tax-delinquent properties in rundown neighborhoods, clean them up and sell them cheaply to developers who were then required to build affordably-priced houses on the lots. But the City has been remiss about follow-up. Between 2007 and 2017 it spent nearly $10 million for 1,403 lots, yet in 2017 only 362 houses had been built on those lots.

next...

The Emancipation Park Neighborhood

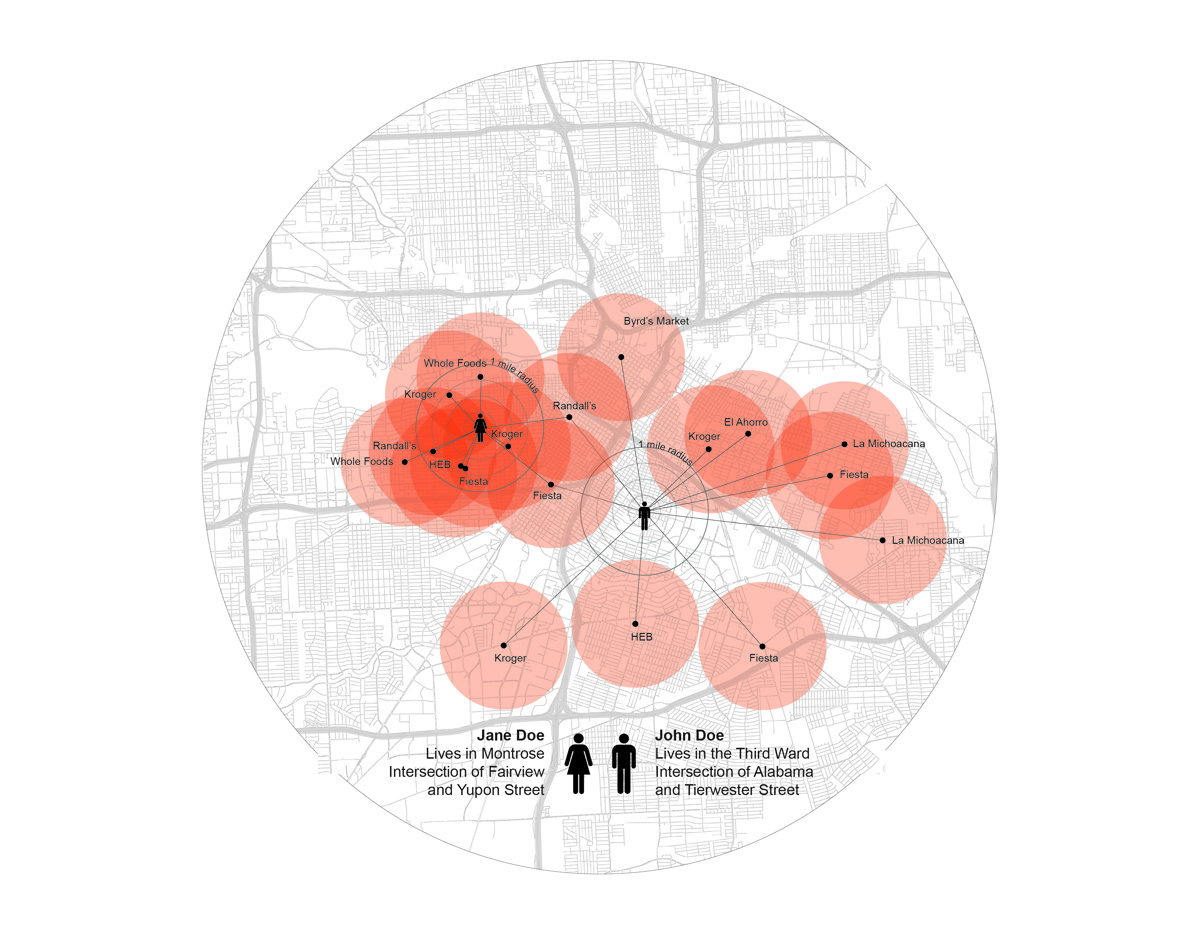

14 A decade later, the maps tap into the resources of information visualization via networked databases. The physical characteristics of Third Ward have all but disappeared under layers of automatically gathered geodata locating everything from grocery stores to evictions and crime hotspots.

Emancipation Park was founded in 1872 by former slaves who pooled their money and bought land to celebrate Juneteenth, the holiday marking the end of slavery in Texas. Donated to the city in 1916, it was for many years the only municipal park open to African Americans. When the City of Houston broke ground for a 33.6-million-dollar renovation of the park in 2013, northern Third Ward was already under siege. High-end townhomes were going up all over, as developers rushed to cash in on the neighborhood upgrade.

next...

Fig. 15. The Emancipation Park neighborhood. MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP), Recommendation for Democratic Engagement. Shared Ownership and Wealth Generation in Houston’s Third Ward, Draft Report, 2015:7.

15 As the level of concern rose in the neighborhood, Project Row Houses partnered with local stakeholders to found the Emancipation Economic Development Council in the summer of 2015. The EEDC promotes community-driven redevelopment engaging longtime residents, most of whom are renters. By increasing the number of rent-controlled apartments available and supporting small business and mixed-use development, they aim to revitalize the Emancipation Park area for its current inhabitants.

The idea came after Rick Lowe invited urban planners from Third-Ward-based Texas Southern University (TSU) to consult with neighborhood residents and make recommendations. They defined priorities for enlarging public discussion and suggested that the community gain more control of land by creating a community land trust. Later, Lowe invited researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Community Innovators Lab (MIT CoLab) who helped set up four working groups to study key community issues. This led to the creation of the EEDC. To effect neighborhood revitalization, the EEDC was advised to adopt four wide-sweeping strategies: build political power, strengthen community ownership, increase housing choice and generate community wealth.

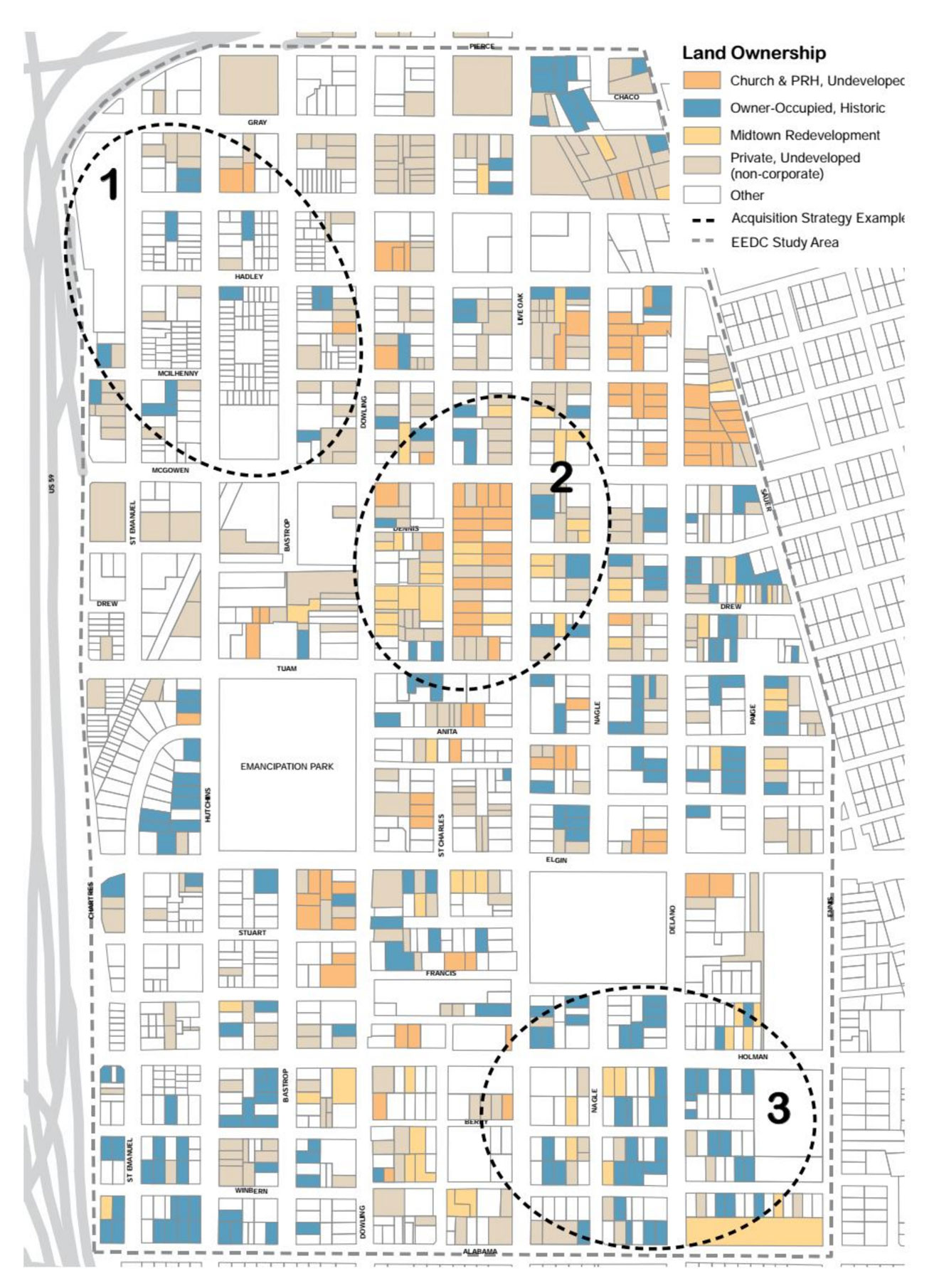

The next year another team from MIT developed a more detailed plan with EEDC working groups. It involves six strategies. The first entails creating a community land trust to buy properties. Families purchase the house and lease the land under it from the nonprofit land trust. This reduces the purchase price and the annual property tax. In exchange, buyers agree to limit the resale price so the house will remain affordable. The 2015 draft identifies older privately-owned properties as “suitable partners for a land trust.” The final report distinguishes three zones with differing development trends and proposes for each an appropriate acquisition strategy. The maps straighten the oblique angles of the earlier maps, using more easily processed rectilinear forms for clarity.

next...

16 Lester King and Jeffrey Lowe’s ethnographic study describes the debates within the EEDC during the early stages of mobilization, as stakeholders attempted to overcome Houston’s “extraordinarily weak community development tradition”. By mutualizing costs, the land trust offers owners who risk foreclosure an alternative to selling to developers. Yet in Houston, building wealth is equated with private property. Workgroup participants expressed this as a conflict between family (retaining full ownership of land means they can leave it to their children) and community (if they or their children sell to outsiders they will be contributing to the community’s demise. Where will the renters go?)

This was not the only attempt at grassroots organizing in the neighborhood. Not long after the EEDC, the Northern Third Ward Consortium was formed in October 2015 to lead a participatory planning effort. The 193-page plan they produced lists their priorities: “empowering our renters”, “saving our history and our homes”, seeding “new community-owned or worker-owned cooperatives and businesses,” hiring “local” and developing “support services”.

By mutualizing costs, the land trust offers owners who risk foreclosure an alternative to selling to developers.

What these efforts have in common is that they focus on redevelopment initiated by neighborhood residents.

next...

Right: Fig.16. “Land Ownership,” MIT DUSP Workshop Report, June 2016.

MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP),

Emancipation Park Neighborhood: Strategies for Community-Led Regeneration in the Third Ward, 2006.

Third Ward as a “Complete Community”

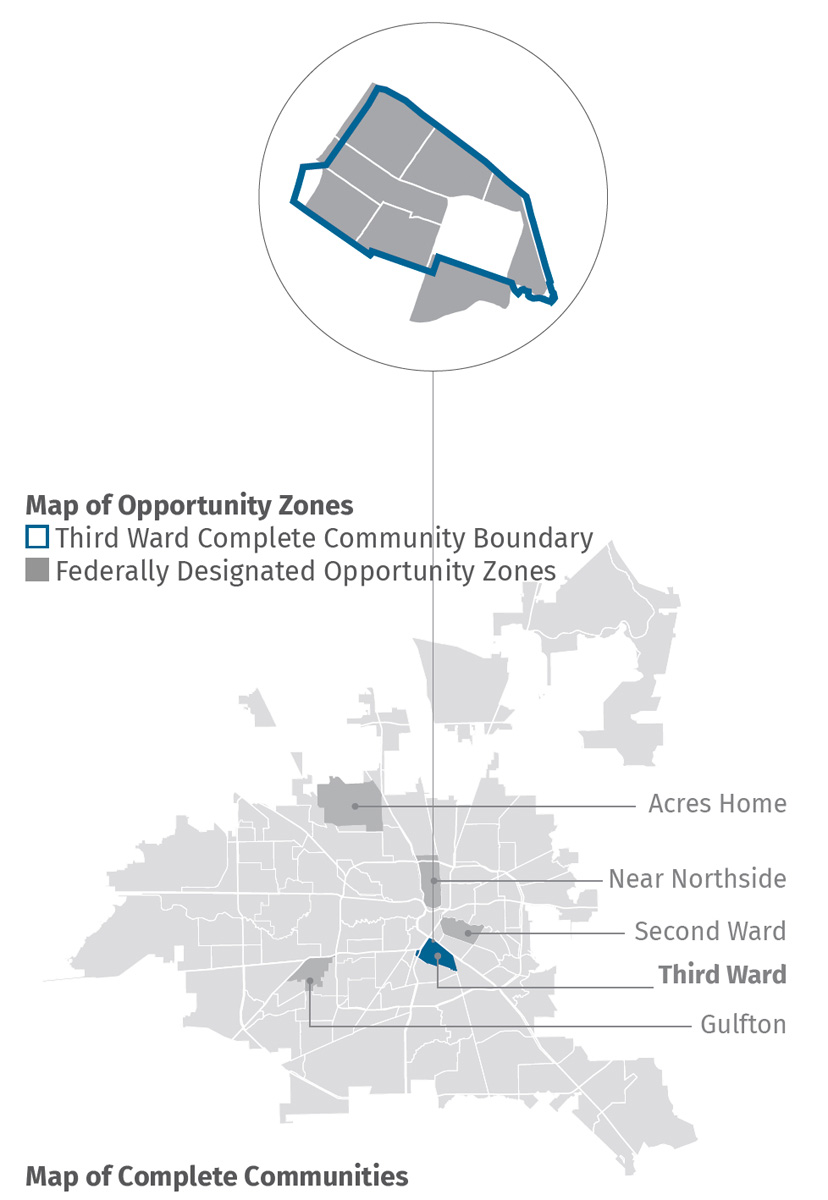

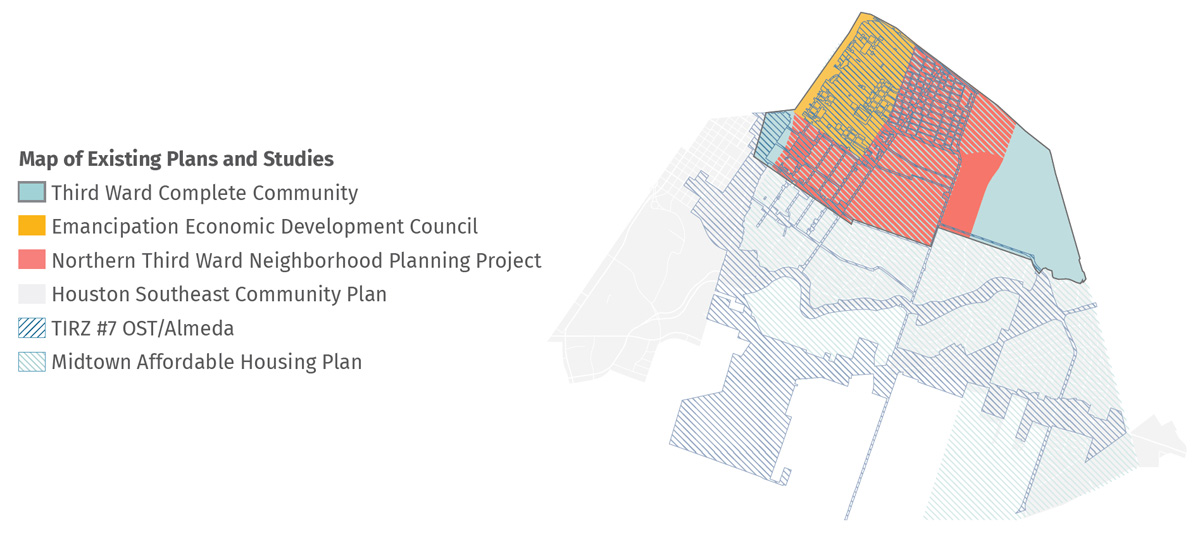

17 Zooming out, by 2018, the maps cover the whole Third Ward, one of five underserved neighborhoods chosen to participate in “Complete Communities,” an ambitious “community-led” revitalization project launched the year before by the City of Houston.

Compiling the findings of its own and five earlier studies, the Third Ward Action Plan identifies no less than 27 goals and 77 projects in nine focus areas, identifying as its top priorities housing, education, and economic opportunities. The same base map is used to make eighteen maps geolocating both infrastructure (sidewalks, police stations, bike lanes) and demographic data (housing by type, median household income, commercial and industrial land use). The maps locate potential assets (active civic clubs, historic landmarks, pre-1940s buildings, grocery stores…), and liabilities (illegal dumping sites, crime hotspots…).

The plan aims to repair and preserve existing housing, particularly “historic” houses built before 1940, to protect them from demolition and maintain the character of Third Ward.

next...

Fig.17. “Maps of Opportunity Zones and Complete Communities,” City of Houston, Third Ward Complete Communities Action Plan, 2018:7. Maps: Community Design Resource Center (CDRC) University of Houston.

Fig.18. “Map of Existing Plans and Studies,” Third Ward Complete Communities Action Plan, 2018:6. Map: CDRC, University of Houston.

Who Owns Third Ward?

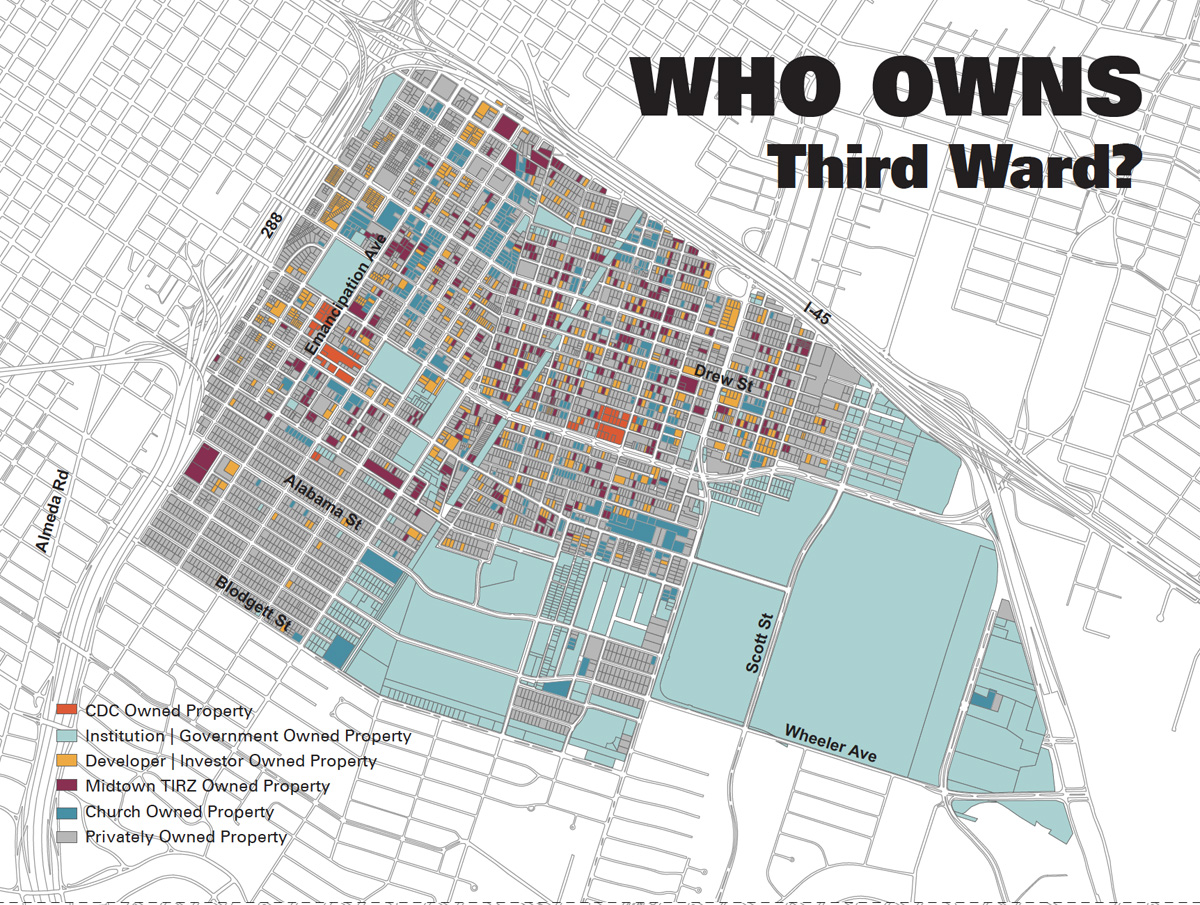

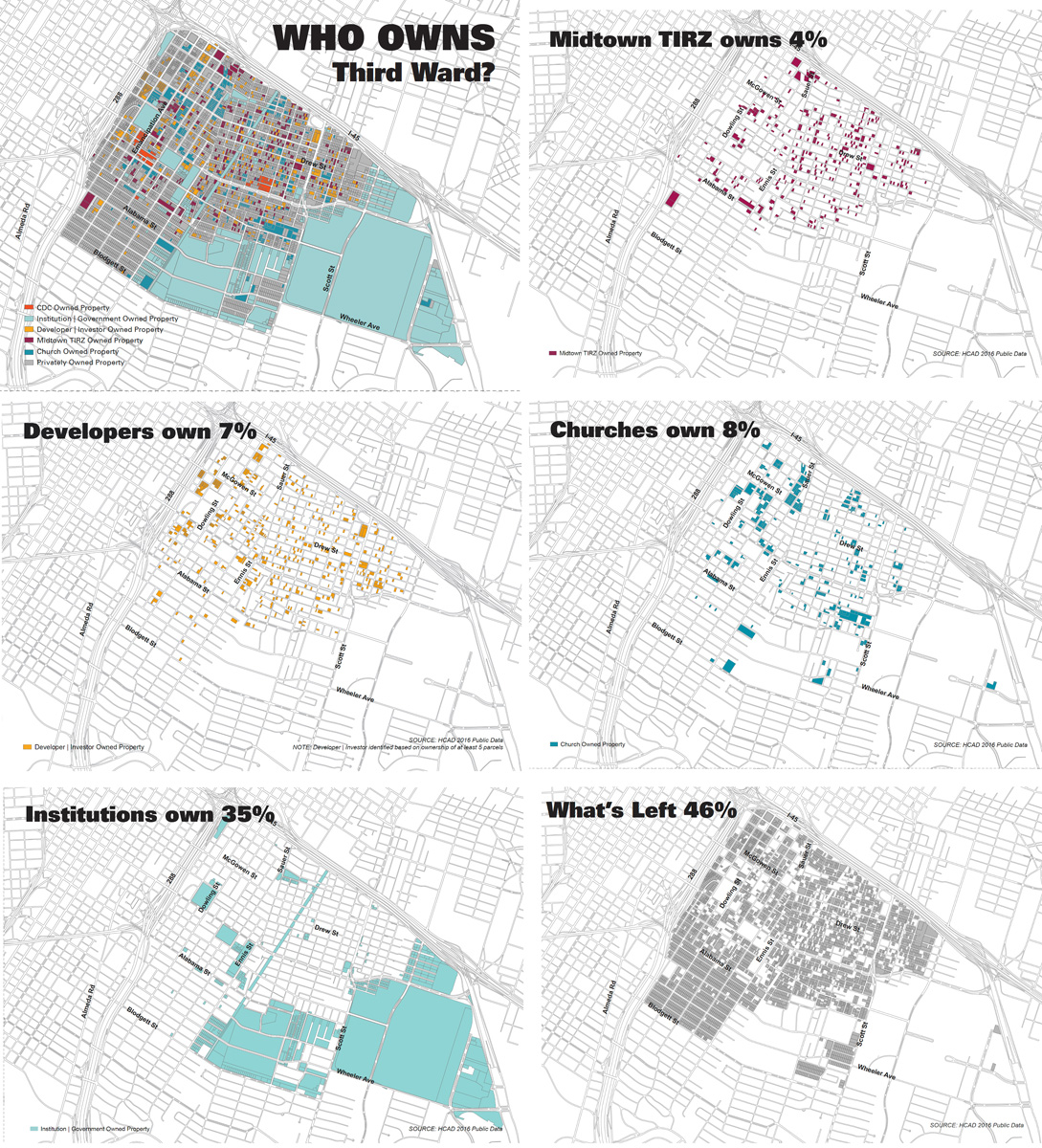

18 Mapping Third Ward assets for the EEDC in late 2016, Susan Rogers and her design team at the University of Houston ask “Who owns Third Ward?” “We used 2016 public data provided by the Harris County Appraisal District — this provides ownership information by parcel,” notes Rogers, “so we divided out churches, we identified corporations, LLCs [Limited Liability Companies], etc. that owned more than five parcels for the developer maps, Midtown TIRZ owned, and then for institutions city, school, university etc. (public ownership)”. The composite view can be broken down to form a series of separate maps showing that, although developers owned 7% of the parcels in 2016, this was offset by the combined holdings of Midtown TIRZ (4%), churches (8%), institutions (35%) and “what’s left” (46%), which meant that Third Ward still was, in a sense, “up for grabs”.

next...

Fig.19. “Who Owns Third Ward?” Maps: “Polis: Towards the Political Reconstruction of the City. The Case of Third Ward” presentation by Susan Rogers at the Museo de Antioquia in Medellin, Colombia, Oct. 22, 2018.

Database Mapping

19 Today database mapping techniques are part of the toolkit of corporate productivity – and bureaucracy. It would be easy to dismiss the neighborhood revitalization plans as ineffectual (or even as a smokescreen for “business as usual.”) Artist Libby Bland takes the planners to task: “Houston’s Third Ward is suffering from both rapid gentrification and planning fatigue. Despite being under the jurisdiction of at least seven different neighborhood and city plans, there are three and four-story townhouses being built on every other block that are all wildly unaffordable to the majority of Third Ward residents. The existence of a plan, without any ability to enforce or fund the initiatives that it details, is largely just a broken promise”.

Why can’t the plans stem the flood of “wildly unaffordable” townhouses roiling the neighborhood? In Houston, zoning doesn’t exist: “development is governed by codes that address how property can be subdivided. The City codes do not address land use”. If the Department of Planning and Development doesn’t regulate land use, how can it “enforce” plans drawn up by local residents’ organizations? “Many public officials seem to have their hands tied because of developers’ influence on decision-making,” writes Isabelle Anguelovski: “It’s a historic issue. Real estate development is at the core of Houston’s economic development”.

At best, the plans serve to coordinate redevelopment efforts and obtain funding.

When Mayor Turner launched Complete Communities in April 2017, he planned to redirect 60 percent of the city’s local and federal housing subsidies to the then-unfunded initiative, but that was before Hurricane Harvey. To compensate the shortfall, he set up an improvement fund to allow the private sector —specifically banks and endowments —to bankroll projects, suggesting that funders form an advisory board to oversee the allocation of funds. In March 2019, a grant from Houston Endowment enabled him to appoint the first director of the Mayor’s Office of Complete Communities to “ensure [that] projects identified through a public engagement process are implemented, funded and managed efficiently”. Projects abound in Third Ward. To convince the City to invest in a community chess park, for example, Ed Pettitt, chair of the Parks & Neighborhood Character Work Group, enlisted volunteers to build a prototype on a vacant lot loaned by Third Ward developer Ciara Jarmon and arranged with local merchants for donations of picnic tables, signposts, planters and bike racks.

next...

IV. “(Re)Framing” and “Remapping”

20 Most of the artistic mappings reframe the neighborhood to highlight underrecognized African-American cultural values. If their authors believe, as Henri Lefebvre wrote, that “new social relations demand a new space”, then producing that space requires developing new representations.

next...

Writing Community

21 The Communograph map (2015) grew out of Communograph House, a multimodal project built by Ashley Hunt together with six Houston artists (Regina Agu, Journey Allen, Lisa E. Harris, Rebecca Novak, Ifeanyi “Res” Okoro and Michael Kahlil Taylor) and fellow Angeleno Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle as part of Round 35 (2011). In the past Hunt has mapped what he calls “the aesthetics of mass incarceration" (The Corrections Project).

The title Communograph was chosen “to combine ‘community’ with ‘writing,’…so as to ground this research in a writing of community from the perspective of the community itself.” Both map and network, it mobilized “five research platforms,” including an exhibition, two public conversation series, two tours, a temporary “welcome center” for Project Row Houses and a blog realized by University of Houston students. Public art practitioners Mel Chin, Rick Lowe, Mierle Laderman Ukeles and Shrimp Boats Project gave lectures at the University of Houston. Photographer Ray Carrington and historian Stephen Fox led tours of Third Ward. The exhibiting artists organized “Sidewalk Talks” on such topics as “Entrepreneurship in the Third Ward” (Regina Agu).

next...

Fig.20. Ashley Hunt, Communograph Map (2015) printable map 11X16 in.

22 The final map, designed by Hunt, shows the main PRH campus on its own (recto) and in its neighborhood (verso). The simplified rectilinear design aligns it with earlier PRH walking maps while the flat blocks of color evoke the visual identity of a museum outreach program. This latter-day mappamundi crowds information into every available space. Inserts picture landmarks like the Eldorado Ballroom, Six-Square House and Carl Hampton Memorial Park (the former headquarters of People’s Party II whose founder was killed by a police sniper in 1970). Domino tiles punctuate the speech scroll winding around the outer edges. Domino games are a leitmotiv both at PRH and in the neighborhood. The flip side situates the campus in greater Third Ward and tells the story of places like Riverside Bank, Texas’s first Black-owned bank, founded in 1963.

next...

Siting History

23 With Monuments: Right Beyond the Site (2014), a collaborative “map” running through all seven art houses and connecting them to sites in the neighborhood, Otabenga Jones & Associates draw attention to “individuals, institutions, and events” that have significantly marked Third Ward history. The installations highlight traditional strategies used by African-Americans to enhance their spaces and “celebrate the values of cooperation, entrepreneurship, self-determination, resistance, and communal responsibility”. For Round 40, O.J. & A. represented key neighborhood sites in the exhibition spaces and placed commemorative plaques at two of those sites.

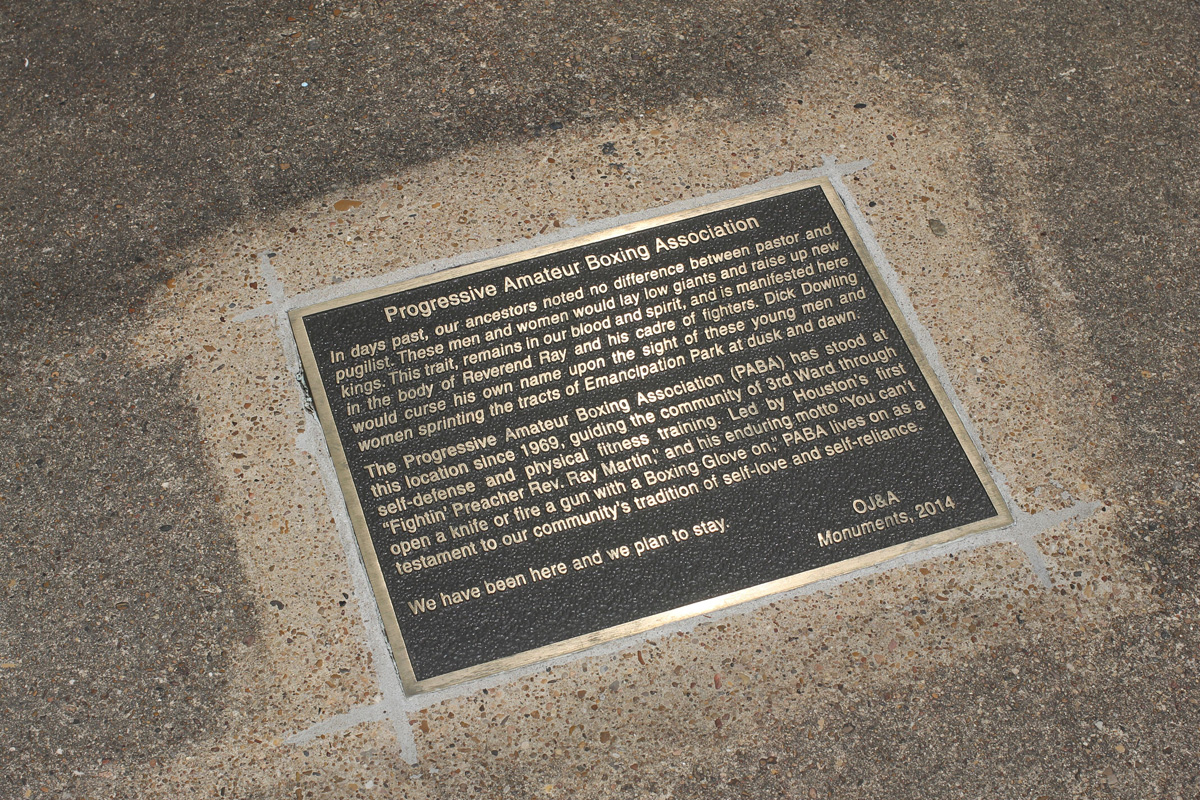

next...

Fig. 21. Above: Plaque “Progressive Amateur Boxing Association”. Otabenga Jones & Associates, Monuments: Right Beyond the Site (2014) Round 40, Project Row Houses. Photo: Alex Barber.

Left: installation “Lanier East Hall Men’s Dormitory”. Photo: Alex Barber.

24 In May 1967, three years before Kent and Jackson State, Houston police raided the Lanier East Hall Men’s Dormitory at Texas Southern University following a student demonstration. To intimidate protesters, they fired thousands of rounds of ammunition and trashed students’ belongings in what has been called a “police riot”. Even as it “reenacts” a period photograph, OJ&A’s installation revisits sixties aesthetic debates, using the skewed perspective of Daniel Spoerri’s picture-traps (in 1962, Spoerri rotated an entire room in the Stedelijk Museum so visitors felt like they were walking on the wall) layering it with anthropomorphic piles of clothing. Here the pillow and bedspread, the stereo speakers, plaid shirts and red suitcases conjure up the young people whose rooms, and lives, were turned upside down, leaving viewers to imagine the impact of the bullets.

In the house devoted to the Progressive Amateur Boxing Association, white punching bags hang from the rafters to form an “all-over” environment, a ring delimited by four parallel red lines on the walls. Jamal Cyrus notes that it “was made in reference to a Buddhist martial arts training room.” Founded in 1968 by the Reverend Ray Martin, “Houston’s First Fighting Preacher,” the P.A.B.A. “fights crime, drugs, racism” by teaching kids how to box. As Martin puts it pithily, “You can’t open a knife or fire a gun with a boxing glove on.” The artists embedded a bronze plaque in the sidewalk outside the Association’s headquarters. Another plaque commemorates the former free health care facility “People’s Party II: Carl B. Hampton Free Clinic” (1970-1971).

Other houses represented the Blue Triangle YWCA and the Unity National Bank (formerly Riverside Bank), the latter in the form of a shrine: crowd-control rope and stanchions lead to a large boli-like figure with an opening at the top, “a giant, Afrocentric version of a piggy bank”. The sixth house showcased hand-painted signs for local businesses by traditional Third Ward craftsmen Israel McCloud, Bobby Ray, Walter Stanciell and V. Woodard, and the seventh served as an education house - a venue for workshops, lectures and gatherings.

The Animating History Project (2016) draws on the 1949 Houston City Directory to build “excitement about potential change in the Dowling corridor”. Under the direction of three professors at the University of Houston, Susan Rogers, Ronnie Self and Fiona McGettigan, students in Architecture and Design teamed up with peers in the College of Art to research, build and place in the physical landscape 22 six-foot high map pins showing prominent Dowling Street businesses.

next...

Fig.22. University of Houston, College of Art and College of Architecture and Design, Animating History Project, 2016: 6 of the 22 six-foot tall map pins. This project was a collaboration among Fiona McGettigan’s students in the College of Art, and those of Ronnie Self and Susan Rogers in the College of Architecture and Design.

25 Shaped like the 20-pixel teardrop icons from online maps, the site-specific sculptures contrast views of successful establishments with the vacant lots and boarded up buildings that have replaced most of them. The structures recall Aram Bartholl’s Map (2007), a “life-size” red marker erected in cities like Berlin and Taipei, its proportions scaled to those of the Google Maps icon in maximal zoom factor. While Bartholl’s nine-meter tall pin superposes map and territory to state the obvious, Animating History distributed the familiar icons along the city thoroughfare so passers-by could imagine what the neighborhood had lost. Implicit to this vision is what it might become.

next...

Fig. 23. Researchers compared a recent aerial photograph of the area with the same swathe of Dowling Street from the 1951 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of Houston, using the 1949 Houston City Directory to identify the businesses that had disappeared. Maps courtesy CDRC, University of Houston.

26 Why settle for anonymous big-box stores with huge parking lots when residents could find inspiration in the wide range of neighborhood shops that their elders could once walk to? Writing about the project, Adelle Main conjures up the prosperity of that bygone era merely by listing their names: Nanking Food Market, People's Foot Health Shop, Johnson's Dinette, Bartholomew Shoe Repair, Dowling Junk and Supply Co., M&M Optical Co., Brooks PM Detective Agency, Ann Beauty Shoppe, Bryant’s Poultry Co., Webster Appliance Co….

next..

Fig.24. Marc Newsome aka Marc Furi, I Love 3W. Round 47, 2017. Photo by the artist.

27 Nostalgic “ode to the Historic Third Ward,” satire denouncing the pitfalls of gentrification, parody of a classic marketing campaign, Marc “Furi” Newsome’s I Love 3W mixes its metaphors with verve. Part of Round 47, “The Art of Doing: Preserving, Revitalizing and Protecting Third Ward” (2017), it featured within its row house a Monopoly “Gentrified Edition” mural, an outsized pair of dice, a game table and a set of photos of Third Ward landmarks. Outside, painted on the façade, was the giant logo inspired by Milton Glaser’s I [heart] NY. The installation was completed by three real-estate signs: a house-shaped "Home for Sale" and two hearts on the front steps reading “Open House” and “I’m Gorgeous Inside.” Instead of Boardwalk and Park Place, the properties players can purchase include South MacGregor Way, Cuney Homes (Houston’s first public housing complex) and The Bottoms – a steal at just $60. Minimal outlay for maximal profit: a speculator’s dream! The Outta Here Moving Company appeared, along with greedy real-estate developers and calculating homeowners, in the artist’s 2008 short film “Here Comes the Neighborhood— A Gentrification Comedy.”

The Monopoly game allows ordinary people to play Cornelius Vanderbilt, eliminating competitors and controlling industries. Players amass fortunes from rent paid by others landing on their properties. Yet the objective is not to accumulate wealth, but “to bankrupt your opponents as quickly as possible. To have just enough so that everybody else has nothing”. The Landlord’s Game was originally designed in 1903 by Elizabeth Magie to denounce the robber barons of her time - the Carnegies and Rockefellers. With the idea that playing it would make people realize that private ownership of land was wrong (or as Henry George claimed, an “erroneous and destructive principle”) Magie “created two sets of rules for her game: an anti-monopolist set in which all were rewarded when wealth was created, and a monopolist set in which the goal was to create monopolies and crush opponents”. She thought players would prefer the first, morally superior set of rules. But it was the second version, aggressively marketed by Parker Brothers, that became the Monopoly we know. By feigning to sell Third Ward landmarks, this “Gentrified Edition” brings the Landlord’s Game into the twenty-first century. A community land trust, anyone?

next...

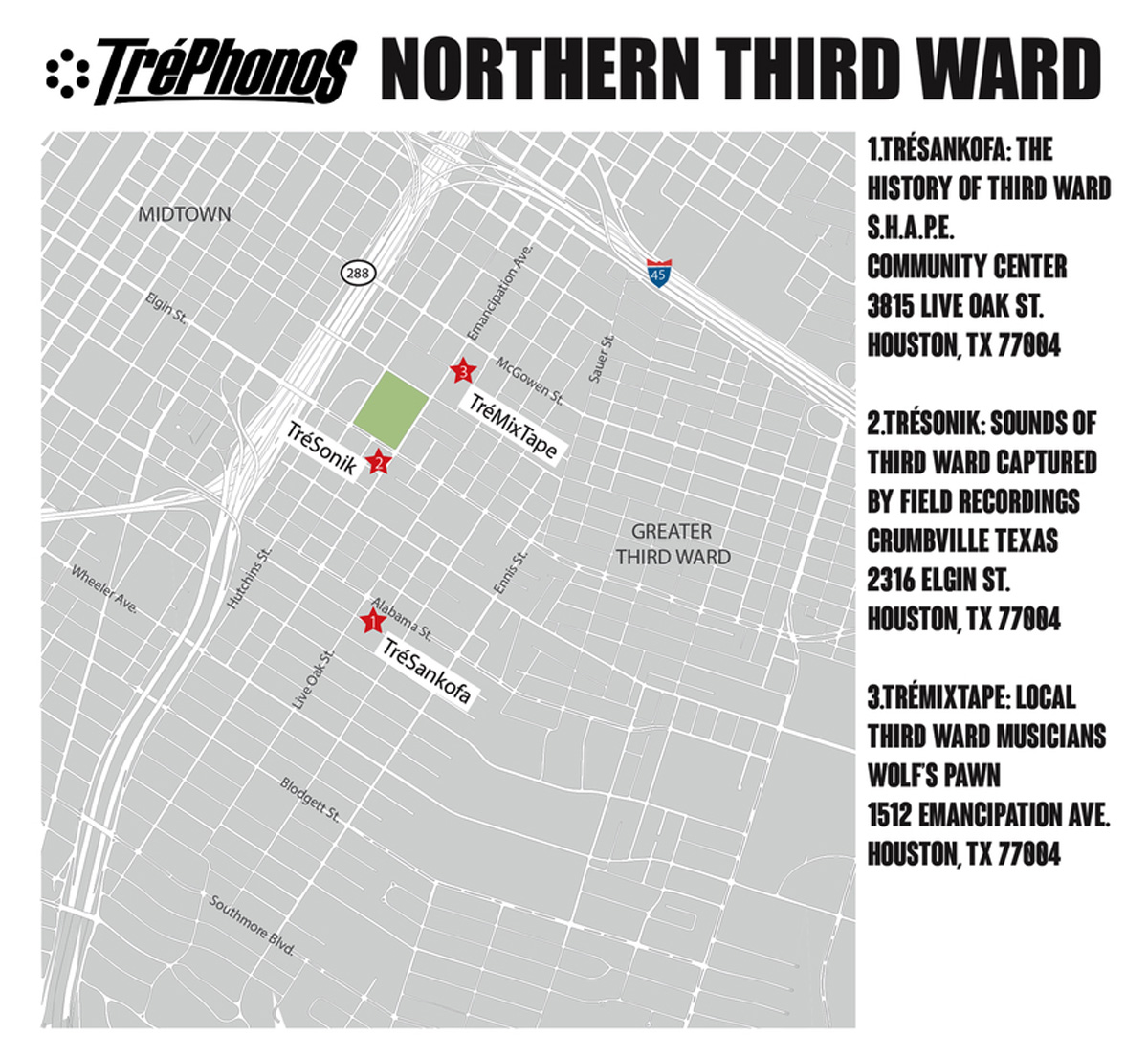

28 For The TréPhonos (2018), Jeanette Degollado, Matt Fries and Julian Luna retooled old payphones to play authentic Third Ward sounds, and placed them at strategic neighborhood sites to form a “map” embedded in the territory. Seeing themselves as “author-producers,” the trio engaged residents of The Tré to provide 100% local content: “the payphones all have ‘ambassadors’ who are also the curators of the phones,” notes Degollado, mediators who connect the neighborhood and the world at large. At the bakery Crumbville, TX, TréSonik (curated by Marc Furi) proposes field recordings of neighborhood venues such as Frenchy’s Chicken on Scott Street. Outside the S.H.A.P.E. Community Center, TréSankofa (Kofi Taharka) offers a repertoire of stories told by Third Ward residents, while TréMixTape (Sunny Smith) facing Wolf’s Pawn Shop, features songs by local musicians like Big Brandon Willis and Baba Ifalade.

Mapping helps to create patrimony. Unable to prevent the demolition of Freedmen's Town in Fourth Ward two decades ago, artist-activists today are focused on saving Third Ward before it’s too late. In these maps, they redefine what culture is worth preserving, and why. I Love 3W and The Tréfonos highlight specific Third Ward places that establish its authenticity and uniqueness, claiming Frenchy’s Chicken and The Bottoms as forms of collective cultural capital. Animating History cultivates nostalgia for dentists’ offices and domino parlors that were once part of the everyday landscape.

To preserve a neighborhood, its character, its social fabric, its way of life, “museumification” is hardly an ideal solution. Turning Emancipation Avenue into an African-American Rialto would likely increase real-estate values, even if it brings jobs. David Harvey has shown how the emphasis on qualities unique to a place is used by capital to extract monopoly rent. If preserving historical landmarks can possibly save a few homes from being bulldozed, then cultural tourism would be, at best, a pharmakon - both medicine and poison.

next...

Fig.25. Jeanette Degollado, Matt Fries and Julian Luna, The TréPhonos (2018). Top: TréSonik, a soundscape curated by Marc Furi. Photo: K. O’R., 2019. Bottom: map of the sites, Jeanette Degollado, 2018.

Taking Back Third Ward

Fig.26. Top: Phillip Pyle II, Coming Soon Whole Foods Third Ward, sign, 2012. Photo: Phillip Pyle II. Bottom: Susan Rogers’s map of grocery store locations in Houston (2011) shows Third Ward to be a “food desert”. Rogers and Oran, “Food For Thought”:38.

29 Another kind of “mapping” consists of carrying out ephemeral actions on the ground to modify onlookers’ perception of a territory.

Phillip Pyle II has undertaken what he calls “community outreach” in the form of guerrilla street art. In August 2012 a sign displaying the logo and font of a well-known Texas chain appeared overnight on a vacant lot at the corner of Holman and Dowling Streets. It read "Coming Soon, Whole Foods Third Ward.” Its makeshift appearance (the edge of the sign behind it is still visible) didn’t stop it from being taken for the real thing. “A popular local real-estate blog posted a photo of the sign and the comments ranged from delight to fear,” notes the artist, “Existing Whole Foods locations in Houston answered calls from disgruntled residents of other neighborhoods asking why Whole Foods wasn’t coming to their area. After a weekend of news cameras and buzz, the city was told to remove the sign by Whole Foods themselves”. Although the upscale organic franchise recently bought by Amazon may not be a good fit for the neighborhood (who said its food was affordable?), Pyle II claims that his sign “helped create a feeling in the Third Ward that maybe it did deserve a grocery store or at least a place where vegetables could be purchased”. It laid the groundwork for an unrealized project - the Emancipation Park Community Association (EPCA) , a precursor for the EEDC, for which Pyle II designed signs.

next...

Fig.27. MF Problem, Mobile Block Party flyer (2011).

30 Autumn Knight and Robert Pruitt, working together under the moniker MF Problem, have organized several events that temporarily remap places in Third Ward. In the summer of 2011, the neighborhood had undergone a wave of thefts, and the Mobil station at the corner of Francis and Dowling streets was the site of a thriving drug trade that made people feel unsafe at night. Pruitt notes that “in the daytime it’s really pleasant, people with families and kids. But when the sun goes down, it becomes almost dangerous”. After discussion with the police and the owner led to nothing, they decided to displace the traffickers by throwing a party in the gas station’s parking lot. They wound up hosting four Mobil Block Parties. Party-goers brought food for a potluck dinner and danced to music provided by a local DJ. The artists stated that “Engaging that corner was an attempt to “‘take back’ part of our neighborhood lost to illicit activity”.

next...

Fig.28. MF Problem, flyer for A Sunday Social, July 7, 2013. Image courtesy Autumn Knight.

31 Two years later, when the real-estate website Neighborhood Scout drew the nation’s attention to the criminal potential at the intersection of Sauer and McGowen Streets, the duo decided to host an afternoon social on that very corner. As a public art event, A Sunday Social was meant “to counter the temporary yet damaging description of this area,” by drawing on “rural/Southern/African American traditional picnics, socials, and jubilees that include dancing, live music, food, and socializing.”

Guests were encouraged to dress in their Sunday Best and “bring a dish to share”. The documentation on the artists’ website show the trappings of a picnic complete with tablecloth and paper plates, boom box and barbecue, attended by a joyous group of PRH stalwarts “fellowshipping” and posing for photos.

next...

Fig.29.The Black Guys, 24 Hours, performance, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-iCh6zXN7K8 Video: Phillip Pyle, II. Screenshot from the video.

32 Another instance of performative hanging-out was 24 Hours (2014), a “behavioral event” performed by The Black Guys (Phillip Pyle II and Robert Hodge) at a Third Ward bus stop. The bus stop dedicated to blues singer Lightnin’ Hopkins, designed by Robert Hodge, was located on the Project Row Houses campus just opposite the Mobil station. Referring to Houston duo The Art Guys’ 1995 performance working 24 hours non-stop as clerks at a Stop-N-Go convenience store in the Museum District, The Black Guys’ homage involved interacting with bus riders and passers-by as well as observing informal neighborhood activities: “Sitting at the stop, Pyle points across the street to a bungalow behind a pile of garbage that spills into the street. ‘That's a squatter house,’ he said. Next door, a squatter smoke house. The illicit activity that sometimes takes place is part of the reason the duo chose a bus stop for their homage to the Art Guys. ‘We're kind of reclaiming our bus stop back,’ said Hodge”.

In their analysis of these three informal works, Willie Jamaal Wright and Cameron “Khalfani” Herman conclude that they are non-institutionalized, provisional rather than permanent, they create new publics, and “pose the continued existence of alternative geographies in the Third Ward that do not fit in the city and developers’ restrictive model for neighborhood development”.

next...

Conclusion

33 “Houston has shown over the past ten years that it has little to no regard for the history of its neighborhoods,” says Rick Lowe in the documentary Third Ward TX (2007), “it is very business friendly. And what that means is it puts the goal and objectives of lucrative business above the human value of the neighborhood.”

This may be changing, slowly, as neighborhood activists - artists, architects, designers, social scientists, nurses, business owners, builders… - organize to resist gentrification and make their voices heard. To rebuild community, they begin on the ground. They tear out old wallpaper and renovate houses, they put mulch around trees for a chess park.

Third Ward may still be a “food desert”, but it has grown oases: NuWaters Food Cooperative (2014) sells fresh fruits and vegetables from its urban farm; Ella Russell proposes freshly-baked pastries at Crumbville, TX (2016). Nearby Doshi House serves vegan paninis, fajitas and curries. Third Ward may lack stores, but it cultivates entrepreneurs. To build community wealth, EEDC chair Assata Richards has helped to found two worker-owned cooperatives: The Third Ward Cooperative Community Builders (2019) operates throughout Greater Houston, and the certified nursing assistants who form the Third Ward Community Care Cooperative (2020) provide home care to Third and Fifth Ward residents. In 2018, when the City of Houston set up a city-wide non-profit community land trust, she became its first board president. Its goal was to place 1,100 homes in its care within five years.

As they remap their neighborhood they produce a counter-power. Long-term relationships allow plans to remain in a drawer for years awaiting funding. With volunteers, donors and students who earn credits instead of salaries, building for the community becomes possible. It took Row House CDC the better part of two decades but it has built 27 duplexes, and more are in the works.

The database maps give citizen planners a more nuanced vision of the area by augmenting the traditional bird’s eye view with ground-level information collected automatically and imported from multiple databases. Yet the plans detail the kind of neighborhood that Jane Jacobs eulogized in her 1961 book Life and Death of Great American Cities. Against the conventional wisdom of her time, Jacobs argued that mixed use, population density and diversity contribute to a lively neighborhood and make its streets safer. Her vision of a vibrant city is embodied in the intricate sidewalk ballet “in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole”. Houston’s Third Ward still has a way to go – for sidewalk ballets to happen, it will need more sidewalks.

The third form of mapping simplifies, sometimes to the point of caricature, and approaches the problem from a different angle.

It’s the same vacant lot, but it takes on new meaning collectively.

Reframing is the artist’s stock-in-trade. As Assata Richards puts it, “artists reshape reality for us.” PRH’s founders did that from the outset: You say shotgun shacks are substandard housing, we say they’re a priceless cultural heritage. Others followed their lead. Neighborhood Scout’s statistics say that passers-by have a one in thirteen chance of being crime victims at the corner of Sauer and McGowen, MF Problem say that corner is an ideal spot for a Sunday get-together. It’s the same vacant lot, but it takes on new meaning collectively. This requires building trust (to convince people to come) but it is a far cry from “magical thinking.” It is important that the freshly-painted row houses sparkle in the sunlight, that the picnickers wear their Sunday best, that the community taste desirable change.

next...

Acknowledgements

34 The author would like to thank David Abraham, Michelle Barnes, Jamal Cyrus, Jeanette Degollado, Ryan Dennis, Sydney Garrett, Deborah Grotfeldt, Karin Halperin, Sheila Heimbinder, Ashley Hunt, Karen Jennings, Autumn Knight, Nelda Lewis, Jesse Lott, Jeffrey S. Lowe, Rick Lowe, Michael McFadden, Shyriaka Morris, Marc Newsome, Floyd Newsum, Ed Pettitt, Shannette Prince, Phillip Pyle II, Assata-Nicole Richards, Susan Rogers, Bert Samples, Danny Samuels, Jérôme Sans, George Smith, River Teyssèdre, Sheryl Tucker de Vazquez, McKenzie Watson, Carol Zou.

next...

Notes

35

1.Quoted in Andrew Garrison, Third Ward TX (2007).

2.As early PRH volunteer Karen Jennings writes in an email message to the author, May 27, 2018.

3.This is why, in Boyle Heights, Los Angeles, anti-gentrification protests have targeted artists specifically.

4.Sheryl Tucker de Vazquez, email message, July 25, 2018. See her “African-American Art and Architecture: A Theology of Life, Death and Transformation” Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture 86th Annual Meeting, 1998:304-310.

5.John Michael Vlach, “The Shotgun House: An African Architectural Legacy,” in Common Places, eds. Dell Upton and John Michael Vlach, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986:58-78.

6.According to de Vazquez, they were rental properties built by Frank and Katie Trombatore, the Italian immigrant owners of the corner grocery store. “African-American Art and Architecture”: 307. Historian Stephen Fox refers to the 2400-2500 blocks on Holman as “Frank Cash Row” in “The Historic Context & Site,” Live/Work: The Collaboration between Rice Building Workshop and Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas, Rice School of Architecture, 2006:40.

7.From the A.C.S.A. Sheryl Tucker de Vazquez, email message, July 25, 2018. Tucker de Vazquez, “Project Row Houses: an intervention”, ACSA 1997 :160. PRH finally bought the building in 1999 and Rick Lowe renovated it himself.

8.Rick Lowe, interview with the author, July 25, 2018.

9.Shyriaka Morris, email message, September 30, 2018.

10.Danny Samuels and Nonya Grenader, “The Collaboration of Rice Building Workshop and Project Row Houses,” Ryan N. Dennis, ed., Collective Creative Actions, PRH, 2018: 33.

11.Danny Samuels, email message, Aug. 31, 2019.

12.Construct website: https://arch.rice.edu/projects/construct/six-square-house

13.In the early 2000s state representative Garnet Coleman persuaded the Midtown Redevelopment Authority to use funds earmarked for affordable housing in Midtown (where land had become prohibitively expensive) to buy properties in Third Ward instead, through the Midtown Tax Increment Reinvestment Zone (TIRZ). https://midtownhouston.com/affiliated-organizations/mra/. By 2016, the authority had banked 3.5 million square feet of land in Greater Third Ward. Developers who buy these properties from the MRA agree to build “affordable” houses and rental units. Leah Binkovitz, “In Houston, A Radical Approach to Affordable Housing,” Urban Edge Blog, Kinder Institute, June 6, 2018. https://kinder.rice.edu/2018/06/06/houston-radical-approach-affordable-housing

14.PRH website: https://projectrowhouses.org/prh-preservation

15.Danny Samuels thinks that this “keyed each location into a database of other characteristics.” Email message, Aug. 30, 2019.

16.Danny Samuels, email message, Aug. 30, 2019.

17.Danny Samuels, ibid.

18.As a venue for other types of shows, including circulating exhibits. Danny Samuels, email message, Sept. 30, 2019.

19.Danny Samuels, email message, Aug. 30, 2019.

20.Susan Rogers, “Hazardous: The Redlining of Houston Neighborhoods,” OffCite, Oct. 4, 2016. http://offcite.org/hazardous-the-redlining-of-houston-neighborhoods/

21.Deborah Grotfeldt, interview with the author, April 18, 2019. In 2010 Rick Lowe mentioned selling land to developers to be able to buy more strategically-located properties. See Tom Finkelpearl, What We Made, Duke University Press, 2013: 354, n.33.

22.Danny Samuels, email message, Aug. 31, 2019. A few years later The Community Artists’ Collective collaborated with a real estate developer with disastrous results. They wound up losing their property altogether. Michelle Barnes, interview with the author, April 18, 2019.

23.Danny Samuels, email message, Aug. 31, 2019.

24.Jason Hackworth and Neil Smith, “The Changing State of Gentrification,” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 92(4) 2001:464–77.

25.Joe R. Feagin and Beth Anne Shelton, “Community Organizing in Houston: Social Problems and Community Response”, Community Development Journal, 20/2, April 1985: 99–105.

26.Igor Vojnovic, “Laissez-Faire Governance and the Archetype Laissez-Faire City in the USA: Exploring Houston.” Geografiska Annaler 85(1) 2003:19–38.

27.City of Houston Land Assemblage Redevelopment Authority, “Tax Delinquent Properties”, Third Ward Urban Redevelopment Plan (April 2005):3. http://www.houstontx.gov/planhouston/sites/default/files/plans/ThirdWardUrbanRedevelopmentPlanMF.pdf

28.Ibid.:2.

29.The City helped low-income buyers to purchase 2007 houses from 2009 to 2013; but in 2017, among those once-subsidized houses, only 463 were still limited by restrictions to keep them affordable. Rebecca Elliott and Mike Morris, “Lost Money: Officials haven't kept close tabs on Houston's low-income housing fund, which is struggling to meet its mission”, Houston Chronicle, 2017 https://www.houstonchronicle.com/lostmoney/

30.On June 19, 1865 - two years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

31.St. Phillip Missionary Baptist Church, Trinity East United Methodist Church, Trinity United Methodist Church, Wesley Chapel A.M.E. Church, Row House CDC and Sankofa Research Institute.

32.Lester O. King & Jeffrey S. Lowe “We want to do it differently”: Resisting gentrification in Houston’s Northern Third Ward, Journal of Urban Affairs, 40:8, 2018:1171-1172.

33.Dowling corridor development for community wealth building, partnerships with anchor institutions, housing development and CLT, political engagement.

34.MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP), Emancipation Park Neighborhood: Strategies for Community-Led Regeneration in the Third Ward, 142-page Report prepared for the Emancipation Economic Development Council, June 2016: https://issuu.com/mit-dusp/docs/mit_dusp_houston_workshop_report_ju:16.

35.Establish a community land trust, make mixed-use development happen, propose temporary experimental projects in vacant lots, create people-centered green infrastructure, preserve the Third Ward and organize the community. Ibid.

36.Zone 1 has seen much townhome development and rising prices. Zone 2 has many undeveloped lots belonging to churches and Midtown TIRZ while zone 3 has historic owner-occupied homes, undeveloped lots, and despite many demolitions, little new construction.

37.King and Lowe, “We want to do it differently”:1171-1176.

38.King and Lowe:1171-1172.

39.City of Houston, Third Ward Complete Communities Action Plan, 2018:7. http://www.houstontx.gov/completecommunities/thirdward/

40.Susan Rogers, email message, Oct. 1, 2019.

next...

36

41.In 2012, Rogers noted the presence of “nearly 1,000 vacant lots in Third Ward,” adding that the siting of an additional 134 vacant lots owned by the Midtown TIRZ was “wishfully strategic—a lot on nearly every block.” Were they placed strategically, she wonders, “to eliminate the possibility of wholesale redevelopment and the displacement of residents?” Susan Rogers, “Destruction in Speculation,” https://superhouston.wordpress.com/2012/03/14/destruction-in-speculation-5-2/

42.Libby Bland, PRH blog, https://projectrowhouses.org/blog/fellows-update-libby-bland-1

43.https://www.houstontx.gov/planning/DevelopRegs/

44.Isabelle Anguelovski, “How Greening Strategies Are Displacing Minorities in Post-Harvey Houston”, Green Inequalities, The Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability, July 16, 2018. http://www.bcnuej.org/2018/07/16/how-greening-strategies-are-displacing-minorities-in-post-harvey-houston/

45.Jasper Scherer, “Turner looking to private sector for Complete Communities funding”, Houston Chronicle, August 29, 2018 https://www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/Turner-looking-to-private-sector-for-Complete-13192347.php

46.“Mayor Turner Announces Director of City’s Complete Communities Initiative,” March 18, 2019 https://cityofhouston.news/mayor-turner-announces-director-of-citys-complete-communities-initiative/

47.Ashley Hunt, http://correctionsproject.com/wordpress/

48.http://www.communograph.com/

49.According to their official biography, the collective (Dawolu Jabari Anderson, Jamal Cyrus, Kenya Evans and Robert A. Pruitt) was founded by artist and educator Otabenga Jones in 2002. Their namesake is Ota Benga, a Congolese Batwa Pygmy who was kidnapped and brought to America in 1904 as part of an anthropological exhibit at the St. Louis World’s Fair.

50.Artists’ statement. Round 40 was curated by Ryan Dennis. See Ryan N. Dennis, “Art for the People’s Sake,” Gulf Coast Magazine 27/1 2014 and Kelly Klaasmeyer, “Two Third Ward Exhibitions Show the Importance of Perspective,” Houston Press, April 14, 2014.

51.The installations evoke the aesthetic vocabulary of site/non-site, without using Smithson’s terms.

52.Jamal Cyrus, email message May 8, 2020. In the mêlée, one officer was killed by friendly fire.

53.In the collective exhibition Dylaby.

54.This description is based on that of Kelly Klaasmeyer, art.cit. A boli is a Bamana power object.

55.Susan Rogers, email message to the author, Oct. 1, 2019.

56.Adelle Main, “On Dowling”, SuperHouston https://superhouston.wordpress.com/2016/04/13/on-dowling/.

57.Probably the most oft-imitated design since Monopoly, Glaser’s logo, itself based on Robert Indiana’s Love (1965), was part of a 1976 campaign to attract tourists at a time when the city was bankrupt, known more for crimes and garbage strikes than for museums.

58.Richard Marinaccio, quoted in Christopher Ketcham, “Monopoly is Theft,” Browsings. The Harpers Blog, October 19, 2012 https://harpers.org/blog/2012/10/monopoly-is-theft/?single=1

59.Henry George, Progress and Property. An inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions and of increase of want with increase of wealth... The Remedy, San Francisco, 1879. Preface to the Fourth Edition,1880. https://schalkenbach.org/library/henry-george/p+p/pp-into-to-Fourth-Edition.html.

60.Mary Pilon, The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, London, Bloomsbury, 2015. See https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/business/behind-monopoly-an-inventor-who-didnt-pass-go.html

61.Jeanette Degollado, interview with the author, June 14, 2018.

62.Self-Help for African People through Education.

63.“Monopoly rent arises because social actors can realize an enhanced income stream over an extended time by virtue of their exclusive control over some directly or indirectly tradable item which is in some respects unique and non-replicable.” David Harvey, “The Art of Rent”, Rebel Cities. From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution [2012], Verso, 2013: 90.

64.http://swamplot.com/whole-foods-market-flag-planted-in-the-third-ward/2012-08-20/

65.https://phillippylethesecond.myportfolio.com/emancipation-park-community-association. See Carrie Schneider, “Emancipation Park, Emancipatory Art: Flipping the Gentrification Playbook” OffCite Jun. 19, 2017 http://offcite.org/emancipation-park-emancipatory-art-flipping-the-gentrification-playbook/

66.Ibid.

67.Robert Pruitt quoted in Willie Jamaal Wright & Cameron “Khalfani” Herman, “No ‘Blank Canvas’: Public Art and Gentrification in Houston's Third Ward,” City & Society 30/1, April 2018: 89-116.

68.MF Problem, artists’ statement: https://mfproblem-blog.tumblr.com/post/51562718802/sunday-social-is-a-derivative-of-the-mobile

69.Every year the website lists the 25 neighborhoods that have the highest predicted rates of violent crime. In 2013, they identified the Sauer-McGowen area as the fifteenth most dangerous neighborhood in the U.S. https://www.neighborhoodscout.com/blog/25-most-dangerous-neighborhoods-2013. At the time, that part of northern Third Ward had been undergoing gentrification. Artist Robert Pruitt (quoted in Wright and Herman:104) sees the rating as a tool “to gentrify a neighborhood,” by pressuring owners to sell at lower prices.

70.https://mfproblem-blog.tumblr.com/post/51562718802/sunday-social-is-a-derivative-of-the-mobile

71.Leah Binkovitz, “24 hours at a bus stop: It's art.” Houston Chronicle, Dec. 13, 2014.

72.Willie Jamaal Wright & Cameron “Khalfani” Herman, “No ‘Blank Canvas’: Public Art and Gentrification in Houston's Third Ward,” City & Society 30/1, April 2018: 89-116.

73.Paul Watzlawick, John H. Weakland, Richard Fisch, Change: Principles of Problem Formation and Problem Resolution [1974], New York, Norton, 2011:12.

74.Andrew Garrison, Third Ward TX, 2007.

75.Susan Rogers and Maria Oran, “Food For Thought: Mapping Houston neighborhoods reveals a great divide in access to grocery stores and suggests possibilities for bridging the gap,” Cite, The Architecture and Design Review of Houston, Vol. 85, Spring 2011:36-39.

76.Official website: http://houstonclt.org/about-us/. Mike Morris, “City plan to expand affordable housing will rely on land trust, subsidies,” Houston Chronicle, March 1, 2019 https://www.houstonchronicle.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/City-plan-to-expand-affordable-housing-will-rely-13656027.php

77.Despite the difference of scale with commercial developers: for example, in 2019 Enterra Homes was poised to build more than 30 high-end townhomes on Emancipation Avenue in one fell swoop.

78.Jane Jacobs, Life and Death of Great American Cities New York, Random House, 1961:65.

back to top of article...

https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/antiatlas-journal-04-O-Rourke-remapping-the-neighborhood.pdf