antiAtlas Journal #5 - 2022

How To Stop A Deportation Flight

Helen Brewer

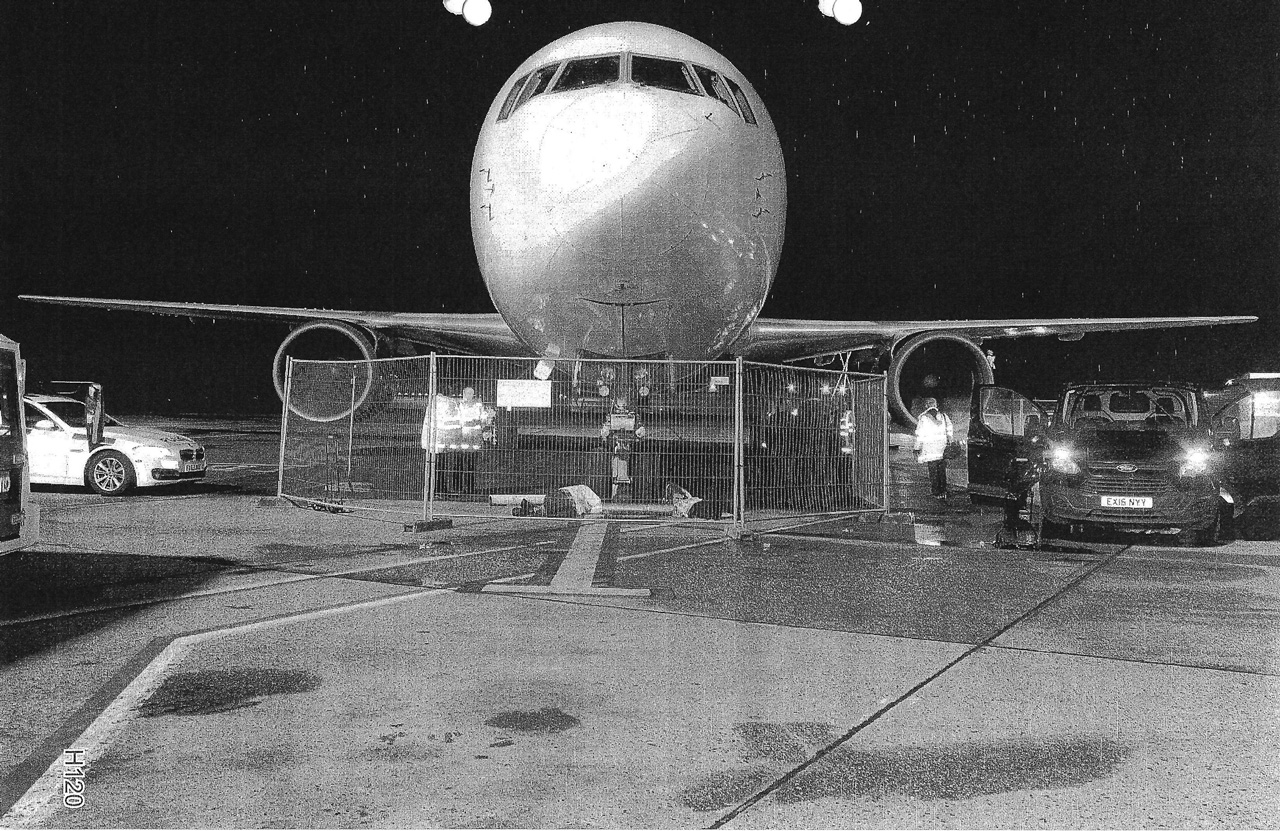

On March 28 2017, a Titan Airways charter flight scheduled to deport 57 people from the UK to Nigeria and Ghana was blocked from leaving that night.

In this article I reflect on the limits and possibilities of the direct action myself and 14 others took to stop the plane and speculate towards the future of anti-deportation resistance in the UK.

Helen Brewer is an activist and PhD candidate at the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Keywords: charter flights, resistance, solidarity, Stansted 15

antiAtlas Journal #5 "Air Deportations"

Directed by William Walters, Clara Lecadet and Cédric Parizot

Graphic design: Thierry Fournier

Editorial office: Maxime Maréchal

antiAtlas Journal

Director of the Publication: Jean Cristofol

Editorial Director: Cédric Parizot

Artistic direction: Thierry Fournier

Editorial Committee: Jean Cristofol, Thierry Fournier, Anna Guilló, Cédric Parizot, Manoël Penicaud

Video screenshot showing the direct action to stop a charter flight from leaving to Nigeria and Ghana on March 28 2017 at Stansted airport. Author: Caspar Hughes, March 28 2017.

To quote this article: Brewer, Helen, "How to stop a Deportation Flight", published on June 1st, 2022, antiAtlas #5 | 2022, online, URL: www.antiatlas-journal.net/05-brewer-how-to-stop-a-deportation-flight, last consultation on Date

I. One action made up of many

1 Direct actions can be thought of as episodic events. Temporal incursions that protest, disrupt, blockade, occupy or halt their target for a specific period of time in order to achieve a specific goal. Afterwards, the operation in which the action intervenes in, more often than not continues unabated. However in some cases, like ours, changes might be made by the State in response: harsher penalties, preventative legislation, alternative schemes or an increase in private and state security.

Direct actions can also be thought of as historically made up of many other actions. Composed of a vast collection of skills, knowledge, experience and relationships, they develop and learn from each other across time and space, from movement to movement. The foundations of many actions are interconnected. Formed by reaching out and working in tandem with different communities with seemingly different interests.

The direct action that took place at Stansted airport in March 2017, was one such action, developed in close dialogue with migrant justice campaigners and caseworkers from across the country. Months of research, discussion and investigation into the deportation process was animated by a history of resistance and movement building that continuously mobilised for an end to deportation and detention. Underpinning our actions in this political ambition meant that our understanding of charter flight deportations would be informed and led by people I’d never met, people whose names I’ll never know, but whose stories and struggle for survival and freedom fundamentally shaped how we approached solidarity and resistance now and into the future.

Anti-detention and anti-deportation resistance have taken on distinct forms in order to resist at all points of the border - inside and outside detention, against immigration raids and evictions, in airport terminals and even online. For some, these tactics are pro-active, like campaigning against an airline’s deportation contract with the Home Office. While others are urgent and responsive to unfolding events, such as mass hunger strikes, raids or scheduled deportation flights.

next...

2 These tactics are by nature, adaptive, temporal and reliant on seizing opportunity, but when persistent, they have resulted in major wins. For example, the cancellation of charter flight routes to Iraq and Afghanistan occurred following concerted efforts by the International Federation of Iraqi Refugees and No Border groups. In June 2011, a blockade by No Border and Stop Deportation groups outside the joint entrance of Harmondsworth and Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centres (IRC) prevented coaches carrying 30 people from leaving for a charter flight to Iraq Similarly in 2009, the same entrance was blocked twice, to protest and prevent the deportation of people to Iraqi Kurdistan

Another memorable action in 2015, saw a coach transporting people from Brook House Immigration Removal Centre for a charter flight to Afghanistan stopped in its tracks for over two hours by a road blockade. The banner that was held up in protest, read 'This Deportation is Illegal' while a woman superglued her hands to the front windscreen wipers

The logistical foundations for stopping the plane at Stansted airport were not new. The tactics we used were built from the struggles of past airport occupations such as Heathrow in 2015 and London City airport in 2016. Though these occupations were clearly tied to protesting climate change and airport expansion, the site of resistance remained the same. In fact, it was only two days after the London City airport action in September 2016 that a charter flight deportation to Jamaica left, prompting some criticism to organisers, who reflected in an interview that, “… people were asking why are you doing this meaningless thing when you could have prevented a deportation - obviously not realising the complexity of the logistics of these kinds of action and how long it takes to plan them and to know where specific flights are going from” (Ghadiali and Grayson, 2021:178).

It occurred to us then, that if an airport can be shut down, then a deportation flight can be stopped.

In doing so, members of the groups Plane Stupid and Lesbians and Gays Support the Migrants (LGSM) came together alongside individuals who recognised the power in drawing these movements together. Because there are no single issue movements. The coordination of all these groups was critical to the action's success and was dependent on a collective exchange of knowledge and experience.

next...

Fig 2: Screenshot of BLM UK’s Twitter feed shutting down London City airport in 2016. Author: Unknown, September 6 2016.

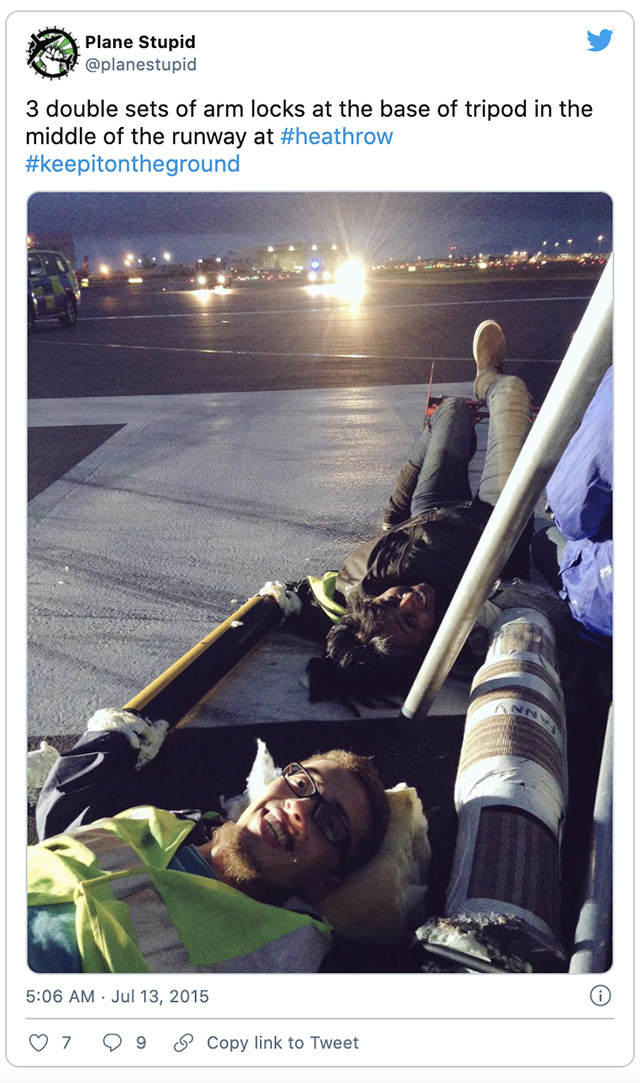

Fig 3: Screenshot from Plane Stupid’s Twitter feed of the ‘Heathrow 13’ direct action in 2015. Author: Unknown, July 13 2015.

II. When resistance is survival

3 To understand how resistance to charter flights developed, it’s essential to understand why charter flights exist in the first place. Writing in 2009, David Wood, ex-strategic director of the UK Border Agency (UKBA) explained why the Home Office started using charter flights in 2001: “It was a response to the fact that some of those being deported realised that if they made a big enough fuss at the airport – if they took off their clothes, for instance, or started biting and spitting – they could delay the process. We found that pilots would then refuse to take the person on the grounds that other passengers would object” (Corporate Watch, 2018).

To facilitate the operation, the Home Office contracts private airlines and hires out whole aircrafts, normally reserved and afforded by the super-rich. Because flights are pre-booked, the Home Office has an imperative to fill the seats on the plane, so it sets itself numerical targets without any regard to a person's individual safety or humanity. This involves targeting certain communities through immigration raids and rounding people up in detention centres and at reporting centres. As these flights only fly to certain countries the UK has “deals” with, there have been regular incidences of people being profiled for deportations to countries that they are not from and told to make their own way back.

The number of people being deported on a single day means solicitors from the few firms that take on last-minute legal aid cases and judges are overwhelmed. Indeed, the Home Office has created a system whereby good counsel and decisions cannot be made in due time, and just in case a person is successful in avoiding deportation, there is a reserve list for people who manage to get off the flight.

So then, charter flights are a way to forcibly deport large numbers of people, quickly and without public scrutiny, using heavy security and clandestine measures. Without knowledge of who is on board, where the plane flies from or when it will fly, people who would have otherwise taken action as an immediate response to the deportation are unable to do so. With the standard ratio of guards to people on charter flights being 2:1, resistance is swiftly crushed. Excessive use of force and the extreme use of restraints during the deportation process is well documented.

Repeated cases of violence, assault and abuse to people made before and during a deportation, call for resistance as self-defence, as life-saving actions against life-threatening processes

According to a report made on a flight to Nigeria and Ghana by HM Inspectorate of Prisons in 2015: “There was a risk that waist restraint belts, which were now embedded in the practice, were being overused and applied whenever there was any ground for supposing that the person might not cooperate during the boarding of the coach or aircraft. They were used on eight detainees during this operation. When the wrists are in the close position (ie. Tight to the hips) they are almost equivalent to body belts, the most extreme and very rarely used, mechanical restraints available in prisons” (HMIP, 2015). Repeated cases of violence, assault and abuse to people made before and during a deportation, call for resistance as self-defence, as life-saving actions against life-threatening processes.

next...

4 In 2010, Jimmy Mubenga was killed with impunity on board a commercial British Airways flight by three G4S guards. He was forced to leave his five children in the UK. Witnesses attest to hearing his last words as: "They're killing me. They're killing me” (Taylor and Booth, 2014). After a six-week trial, Jimmy Mubenga’s killers were found not guilty despite the overwhelming evidence of brutality. More than a decade on and his injustice is a reminder that all deportations are a threat to life. There have been 29 deaths in immigration removal centres since 1989 and many people are on suicide watch days before their scheduled flight. Since January 2007 there were over 19,368 persons on suicide watch across the UK detention estate. One such case, is that of Darren C who was detained in Brook House and brutally attacked when he refused to leave his room before a deportation. His arm was broken and his mouth stuffed with paper.

No doubt, the most distressing incident to come out of “Operation Majestic” - the so-called flight route to Nigeria and Ghana - is the story of Ms. D, a woman with a known mental illness who was reported to have been “at the extreme of non-compliance, resisting at every point and spitting at anyone who spoke to her.” To facilitate Ms. D’s deportation, she was placed in “leg restraints for 10 hours 5 minutes and in handcuffs for 14 hours 30 minutes, continuously in each case” (Miller, 2014). Once the plane landed in Lagos airport, Ms D. continued her resistance and had to be carried off the plane.

For people who are forced onto these flights, resistance isn’t optional. It’s survival.

According to Phil Miller (2014), reports indicated that “Half an hour later, she was sitting on the tarmac in front of the plane with nobody communicating with her. She took all the medication, including anti-psychotic drugs that the [Home Office] paramedics had handed to the local officials who had then passed it to Ms D.” What followed is shocking. Despite the clear signs of a vulnerable woman in extreme distress, Ms. D was abandoned in Nigeria. For people who are forced onto these flights, resistance isn’t optional. It’s survival.

next...

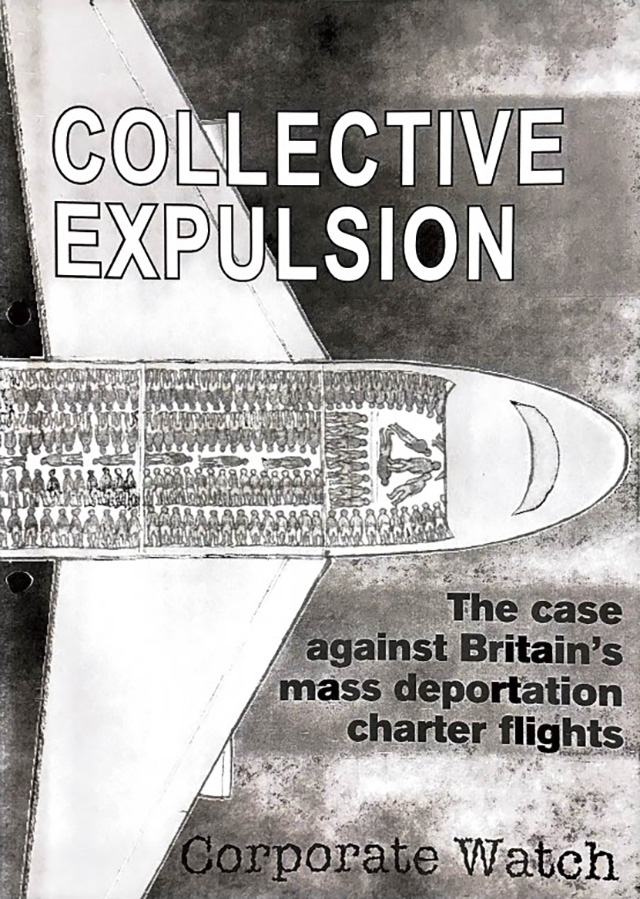

Fig 4: Photocopy of the front page of the Corporate Watch report ‘Collective Expulsions’. Author: Phil Miller, Stop Deportation Shiar Youssef, Corporate Watch, September 2013.

III. What we knew

5 We knew we wanted to stop the deportation flight, however, the actual logistics of action planning would come much later. The first part was to gain as much information as we could. We conducted our research over several months – reading the Corporate Watch report, “Collective Expulsion” (Miller et al. 2013), became integral to understanding the deportation process, its history and the stakeholders involved. Copies of the report were printed and taken with us to the airport while we locked on and used as evidence in our trial.

We looked at what made charter flights different from commercial deportations. Flights happen in the middle of the night or the early hours of the morning, the flights are pre-booked and there is a reserve list. Often nicknamed “ghost flights”, there is little independent oversight onboard, as they operate under intense privacy and security.

When searching for visual references of deportation charter flights, I came across a television interview from July 2015 with a caseworker from the Unity Centre based in Glasgow. The side by side shot of the interview was accompanied by a series of high-resolution photographs of a Titan Airways charter flight by the artist James Bridle. He subsequently sent me footage of a deportation at Stansted Airport which he filmed on the 29th of July 2015 involving a Titan Airways charter plane.

The footage showed people being escorted one-by one by security from a coach parked a few feet away from the plane to its stairway. More than likely handcuffed, they are led up at a pace, two guards to one.

next...

Fig 5, 6 and 7: Screenshots from James Bridle’s video of a Titan Airways charter flight to Nigeria and Ghana on July 29 2015. Author: James Bridle, July 29 2015

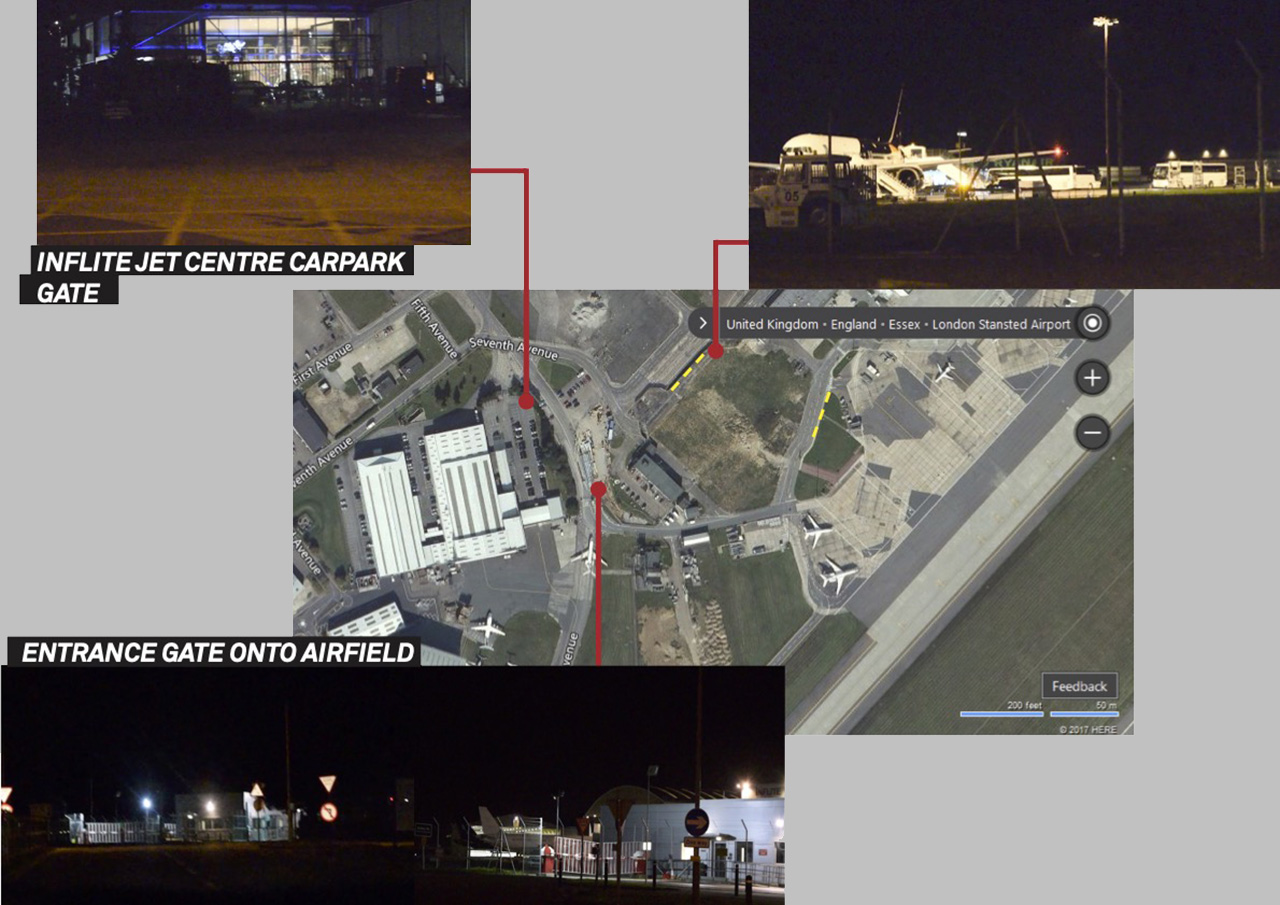

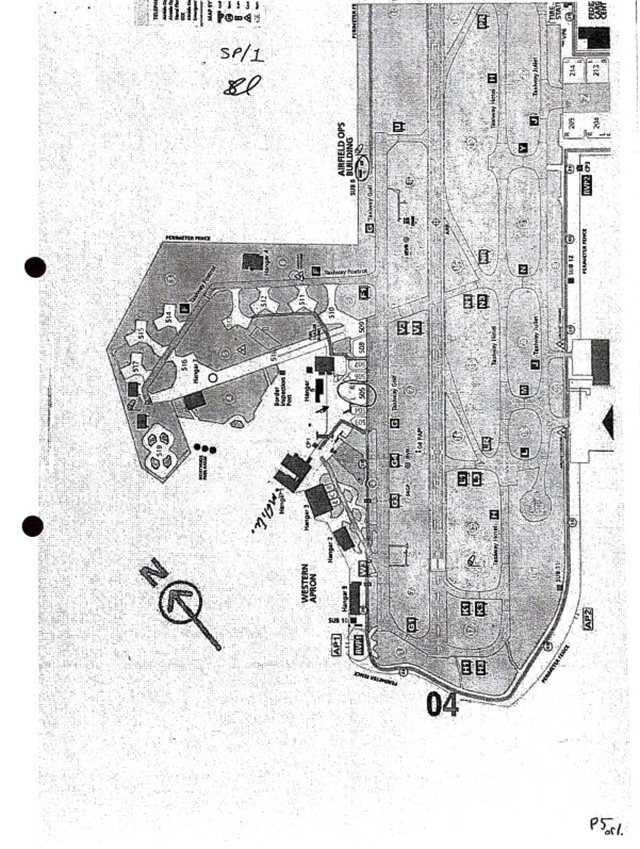

6 Using screen shots of the footage we managed to identify the same plane on Stand 505, locating and cross-referencing the location of the shots to google maps and what we saw on our “reccies” or “reconnaissance” studies of the deportation process.

next...

Fig 8: Site plan of Stansted Airport and the location of the Titan Airways charter plane. Author: Helen Brewer, March 2017.

7 Two months before the action, a series of rolling protests were held by affected communities and campaigners across the UK and in Jamaica and Nigeria to build momentum against the government’s use of charter flight deportations and the known violence perpetrated by private security companies during the process (Hall, 2017). The protests were in anticipation of a charter flight scheduled for January 31 to Nigeria and Ghana. In a phone recording taken by Detained Voices, an online platform that publishes the statements, experiences and demands made by people held inside immigration detention, a woman scheduled to be deported on the flight speaks in fear of what will happen. She talks about receiving a ticket, having no family in Nigeria and finding detention difficult. She mentions that the flights to Nigeria and Ghana happen every two months. And we would also later find out from people with tickets, that they would always fly on a Tuesday.

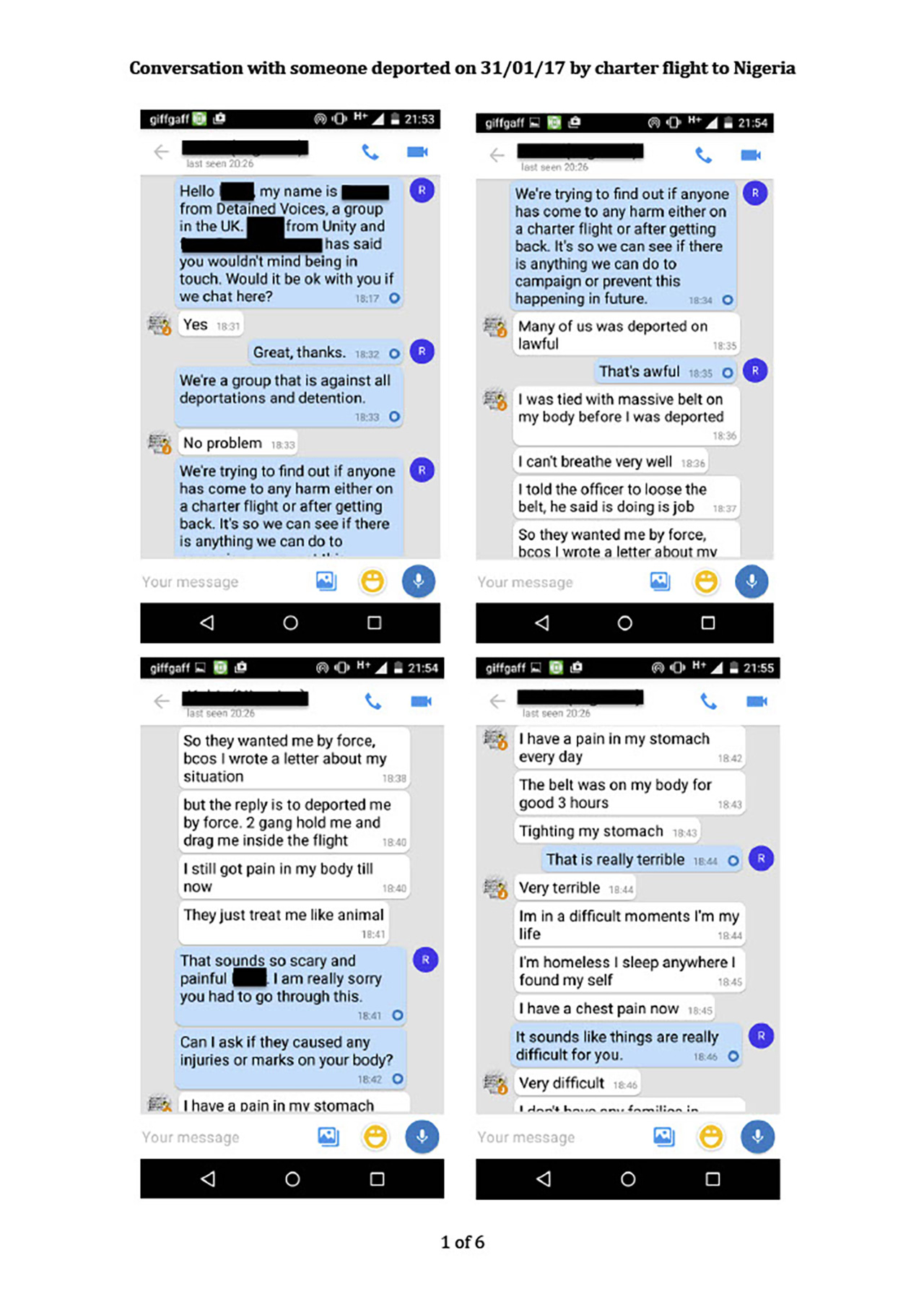

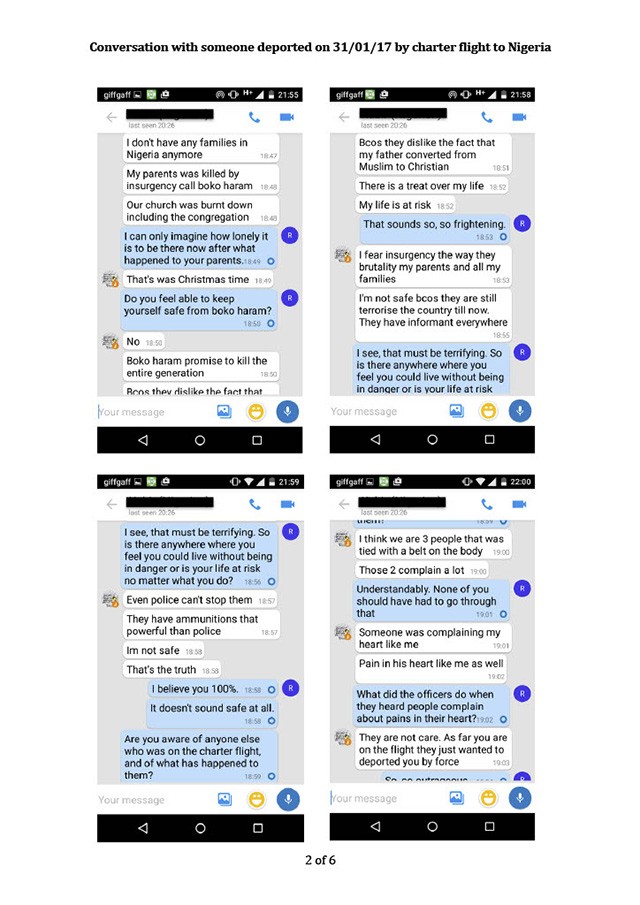

The same flight would also deport Tunde to Nigeria. He had been living in the UK for 10 years awaiting his asylum claim. In a conversation with a member of Detained Voices, he detailed that his family were killed during an insurgency by Boko Haram, when they burned down his church along with his congregation. Left with no family and no home, when Tunde arrived in Nigeria after being deported, he became forced to live as a destitute. He describes “being treated like an animal” during the flight, bound with a waist restraint belt and in pain for the 3 hours it was tied on to his stomach. Furthermore, the Home Office gave him his ticket knowingly on a Sunday when his solicitor was not working. He believes that they were trying to fill the seats on the charter flight.

next...

Fig 9 and 10: Scan of two out of 6 pages of a What’s App conversation between Tunde and Detained Voices detailing his experience of a charter flight to Nigeria on 31 January 2017. Author: Detained Voices, date unknown.

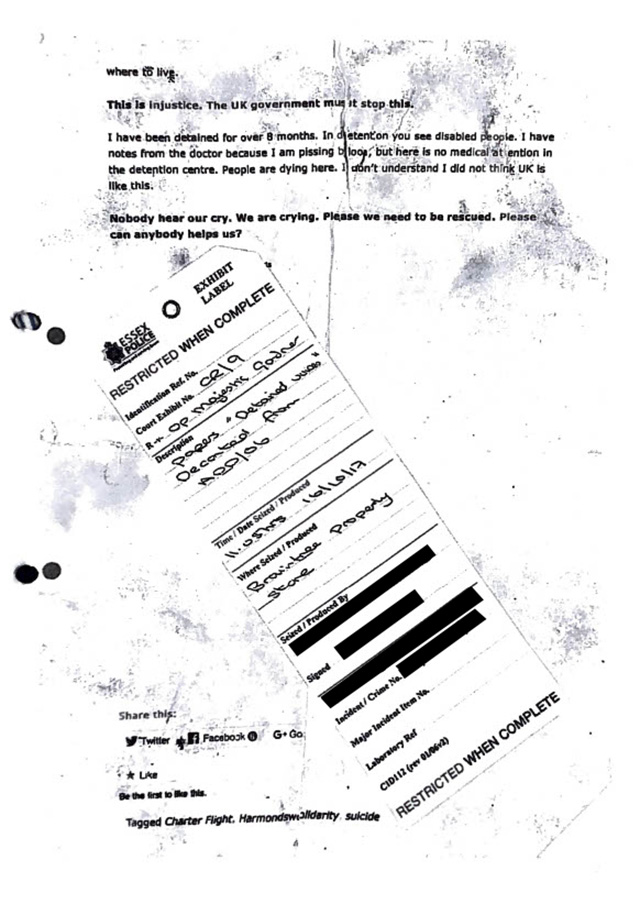

8 Through Detained Voices we became aware of charter flights through communication channels to individuals in detention centres who helped shed light on the deportation process and their experience being taken from detention. There is no publicly available information about who will be on board the charter flight, when it will be or where it will fly from. The testimonies gathered by Detained Voices were crucial evidence and knowledge of the conditions and trauma people in detention faced and felt. The testimonies we read from individuals who were scheduled to be on the flight on March 28 were the stories of people who we learnt were in danger – they were carried with us and read out loud to the police officers who confronted us on the apron of the parked plane and later used as evidence in our trial.

The Detained Voices testimonies we highlighted were used as strategic examples of the extreme impact deportation charter flights have on the most vulnerable people. However, not everyone was a person seeking asylum or a survivor of trafficking, some people had lived in the UK for years and had families, some people were convicted of crimes, some people had served prison sentences, some people had overstayed their visas, some people did not have the right documentation. However none of them deserved to be deported. And it's important we emphasise that. The need to hook on to the most traumatising stories in order to persuade the public was our action’s biggest harm and failure.

next...

Fig 11 and 12: Police evidence of a Detained Voices statement brought with us on the action. This was one of six statements.

Author: Detained Voices, March 17 2017

9 The action only became possible because it was developed in tandem with caseworkers who we knew were supporting people inside detention and had tickets for the flight. Once informed that we had successfully blockaded the plane, the caseworkers were able to find legal support for anyone they could on the flight we stopped within the time that was afforded by the action we took.

We decided to block the plane for two reasons. First, we were certain that if we surrounded the plane, it wouldn’t leave. We were worried that if we blocked a road, the coaches would be able to find another onto the airfield. The same would apply if we had blocked the gates of a detention centre. Plus we would only have been able to block one detention centre which would still have meant that the flight would go ahead with its reserve list. The second reason was because we wanted to create a big enough impact to put deportation charter flights on the map and into public consciousness. The use of disruptive actions to garner public and media attention is a long standing tactic made all the more necessary by the very nature of deportation charter flights’ clandestine operation.

This knowledge formed the basis for our strategy. For example, airports are pinch points for charter flights. For every deportation there may be multiple raids in communities, homes and workplaces, and multiple coaches transporting people from detention centres to airports. But there’s only one plane.

On commercial flights, there are opportunities for a person being deported to resist and educate passengers. The public inadvertently become witness to the resistance and hopefully participate in stopping the deportation from happening. Successful resistances against commercial deportations would have undoubtedly contributed to the escalation of charter flights and the increased securitisation of the deportation regime. Targeting charter flights is first and foremost a strategy to combat the State dissuading resistance.

next...

IV. The “reccies”

10 The first “reccie” was to Harmondsworth and Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre (IRC) near Heathrow Airport. We wanted to work out what time the coaches left the complex and follow them to the airport. The flight, we heard, was leaving for Jamaica that night from Heathrow. We waited in the carpark from 7 P.M., with a thermos full of coffee and snacks to see us through while we watched and it rained. We witnessed one coach arrive, parking directly in front of us. Through the blurry glass of the car's front window, it looked like security staff were unloading big duffel bags of equipment. The coach then drove inside Harmondsworth and Colnbrook’s metal gates while we waited for hours until the early morning. Briefly snoozing but never seeing the coach leave again. We concluded we either slept through it or there was another exit to the centre we didn’t know about.

next...

Fig 13: Reccie outside Harmondsworth and Colnbrook watching the coach unload. Author: Helen Brewer, 2017.

11 The previous week, a few others had cycled to Stansted during the day to ‘scout’ the area on foot. Walking behind the wooded areas which edge the roads parallel to the airport perimeter, the purpose of the reccie was to scout the different available routes to break in. Eventually abandoning all options as it would entail having to walk longer distances to where the plane was parked.

next...

Fig 14, 15 and 16: Scouting the perimeter of Stansted airport. Author: Helen Brewer, March 21 2017.

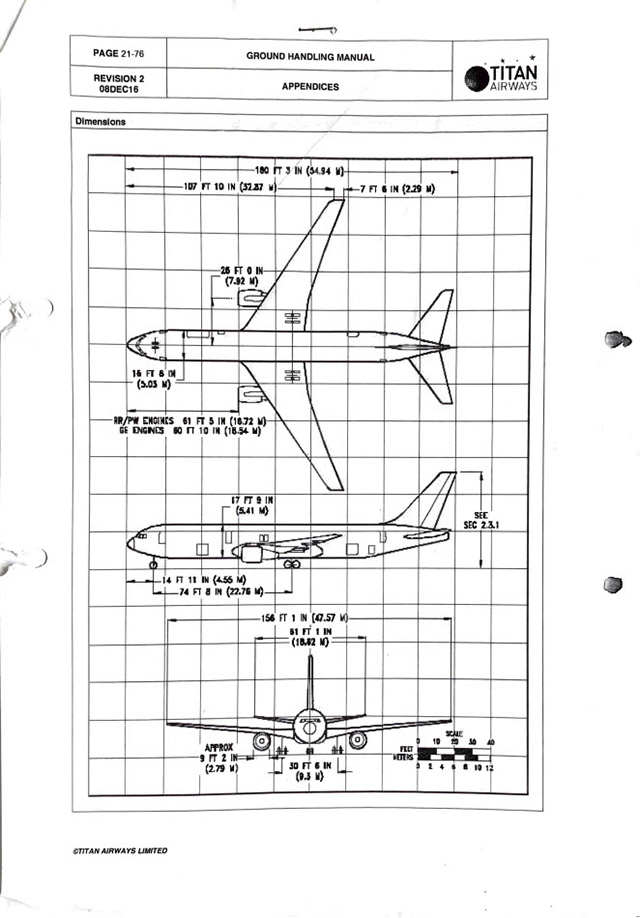

12 The next reccie took place a week before the action. We needed to work out what time the plane left Stansted, where it was parked and when the coaches would arrive. The plane was headed to Pakistan this time, but we knew from our research that it would be the same make and model that would leave for Nigeria and Ghana.

next...

Fig 17: Looking for the plane on March 21 2017. Author: Helen Brewer.

13 It was 9 P.M by the time we spotted the plane. We had been there for over three hours, driving around in circles searching for an indication of the coach's arrival and attempting to get as close to the perimeter fence as possible. The area we were in was located on the outskirts of the airport's main terminals. It looked like a giant industrial park, housing office buildings, airport hangars, warehouses and private departure lounges for private planes including one owned and operated by Harrod’s. We finally parked in a carpark, surrounded by empty cars most likely left by cabin crew or other airport staff on shift.

Slouched down in the front seat of the scout car, I kept my DSLR camera pressed up against me, its lens pointing shakily towards the front window that looked on to the Inflite Jet centre - the known departure “lounge” used for charter flight deportations. Trying my hardest to remain unnoticed in order to get the shot. I first filmed a steady convoy of large white coaches arriving throughout the night into the Inflite centre. I remember thinking how surreal it was to see these vehicles not as the leisurely holiday carriers they represented, but as another sinister device used in the deportation. Each one was followed and guarded by a private security van emblazoned with the insignia of the Capita-owned Tascor security company. The coaches are chartered from detention centres all over the country, carrying people against their will to the Inflite Jet centre where the departure processing can begin. From what we now know, people who are extremely disruptive before a flight are often taken in individual Tascor escort vans instead.

next...

14 From the footage taken that night, I put together a short video of the deportation process for the rest of the group. This reccie was a turning point for the planning of the action. Now we knew where the plane was going to be parked, what time it would depart and what time people would be arriving at the airport. From here, we could determine when the most effective and least dangerous point would be for us to intervene.

next...

Fig 18: Video capturing the process of a charter flight deportation to Pakistan on March 21 2017. Author: Helen Brewer, March 21 2017

15

0:00 - Titan Airways charter plane spotted on Stand 505

0:21 - @ 0020hrs the first coach arrives, followed by a Tascor security van and enter Inflite Jet Centre car park

1:14 - Crew arrives (walking from Titan Airways hangar to Inflite Jet Centre)

1:33 “Royal Blue” catering truck arrives (enters gate to airside)

2:00 - @ 0040hrs the second coach arrives

2:30 - Catering on apron driving to plane

2:42 - Third coach arrives

2:49 - Around 5 - 6 Tascor security vans have arrived to Inflite Jet Centre car park by this time

2:59 - Ambulance and security arrive

3:18 - Fourth coach arrives

3:34 - @0200hrs the coaches leave Inflite Jet Centre carpark and enter gate leading airside

4:40 - Processing at airside gate

5:10 - @0230hrs the coaches drive to apron

5:29 - Boarding

next...

Fig 19: Coaches parked by the stairway while people are forcibly boarded onto the plane on March 21 2017. Author: Helen Brewer, March 21 2017

16 An ambulance was the last to arrive and its presence was a stark reminder of just how dangerous this operation is.

In February 2018, ten people were on board a coach leaving Harmondsworth IRC for a deportation flight to Pakistan when it caught on fire. Instead of evacuating people immediately after noticing the issue, escort staff managed by Tascor decided to handcuff and restrain people inside the burning bus. They eventually evacuated everyone off but only minutes before the vehicle exploded in flames. Faizal, who was one of the people restrained on the coach, told the Guardian: “We couldn’t breathe on the coach because of the fumes. People were screaming: ‘Open the door, open the door.’ But they wouldn’t” (Allison and Hattenstone, 2018). The shocking and distressing manner in which people are treated in this traumatic event is only compounded more by the insistence of their forced deportation.

Our last and final reccie was on the night of the action. A few of us had gone on ahead of the others who would be waiting in a service area nearby. The purpose of this reccie was to ensure that the plane we were going to target was not only the right one but that the action would be effective and safe to go through with. We timed it, waiting for the last coach to arrive at the Inflite Jet centre car park before we called up the others and told them we were on our way to pick them up. We took the last few minutes at the service area to use the toilet (which we shared with G4S security staff on their break before night shift) and gathered our courage.

next...

V. From the first arrest made at 10:07 P.M to the last at 7:58 A.M

Fig 20: Video of the direct action to stop a deportation charter flight to Nigeria and Ghana, March 28 2017. Author: Caspar Hughes.

(March 2017)

17 From where the plane was parked the jet fuel scented landscape of Stansted airport's system of runways and taxiways spread out beyond us in the distance. The night was cold, clear, and heavy with the audible roar of airplane traffic above our heads. Planes were landing and taking off from the runway in a continuous queue of Ryanairs and EasyJets. They could have been heading to the sun-soaked coast of Biarritz, the cosmopolitan city of Dubai or the diplomat laden lake of Geneva, either way none of them could have anticipated that only a few hundred meters nearby, a deportation plane destined for Nigeria and Ghana would be stopped by fifteen people in bright pink woollen beanies.

Between us we carried two tripods made up of six reclaimed scaffolding poles and pushed trolley-loads of lock-on equipment to the wheel and side of the plane, located a short walk away from the perimeter fence we cut into. As we got closer, we could see a huge golden sun emblazoned on its side, the iconic marker of a Titan Airways charter plane. Another way to tell it’s the right plane is from its registration code printed underneath its wing and on its side - in all caps it reads: G-POWD

While walking towards the plane, some of us noticed a staff member with a walkie talkie standing on top of the first stairway leading to the front cabin, we found out later they were calling airport security and the police. At this point, the group split up and four people headed to the plane's front wheel where they used the arm tubes to lock themselves into a circle at its base.

It took approximately seven minutes for the police to arrive.

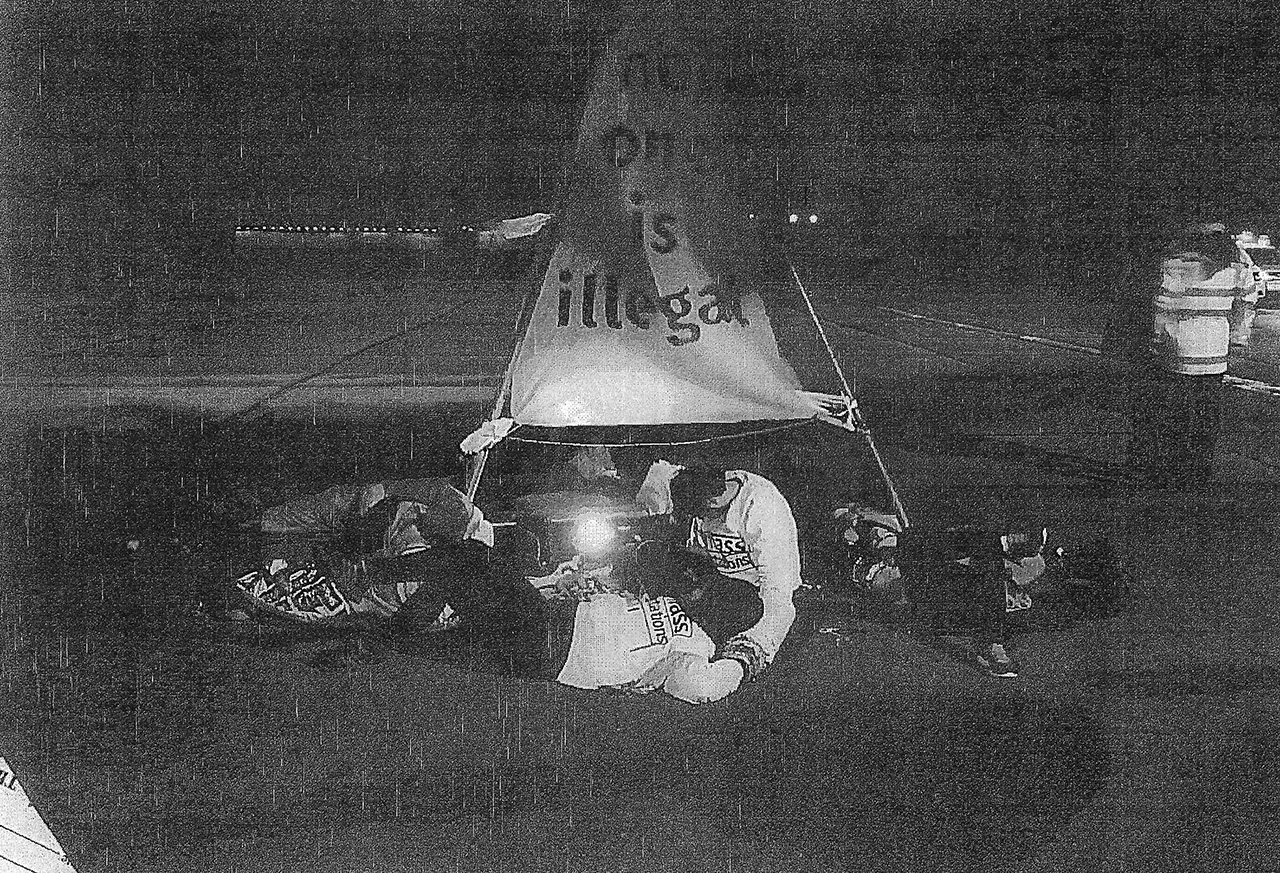

The rest of the group headed towards the passenger stairway behind the wing, where everyone had a job to do - arranging arm tubes, erecting the tripods and positioning the lights which would illuminate the tripod’s attached neon pink banner which read: ‘No One Is Illegal’. Helped by others, I managed to climb to the top of one of the tripods and warn people below about a police vehicle approaching in the distance.

next...

Fig 21, 22, 23 and 24: Scans of police photographic evidence of the direct action, March 28 2017. Author: Unknown.

18 However some of the group had been having trouble with the second tripod which would have held up our second banner reading “Stop Charter Flights - Mass Deportations Kill”. The lost time meant they had to abandon the tripod and arrange themselves with the rest of us before the police made it onto the scene.

Most people had been able to find a free tube and attach their carabiner clip to the metal rod located inside, but some it turned out didn’t even manage to do this and simply stuck their arms inside, giving the impression that they were attached. When the two police officers arrived, all but one of us had managed to get on the ground and “lock on” as he waited to fill in each tube with expanding foam. When the officers spotted him, he gave chase around the plane and behind the stairway attempting to buy more time. Hearing our shouts, he dived towards us to stick his arm inside a free tube, but was unable to lock on before the police jumped on him and dragged him away. All of us shouted at the police officers to let him go fearing they were hurting him. The people closest to him, who were locked on tried to grab on to him, but he was pushed to the ground and handcuffed.

At the same time, the journalist filming us was arrested along with another who was stationed by the perimeter fence.

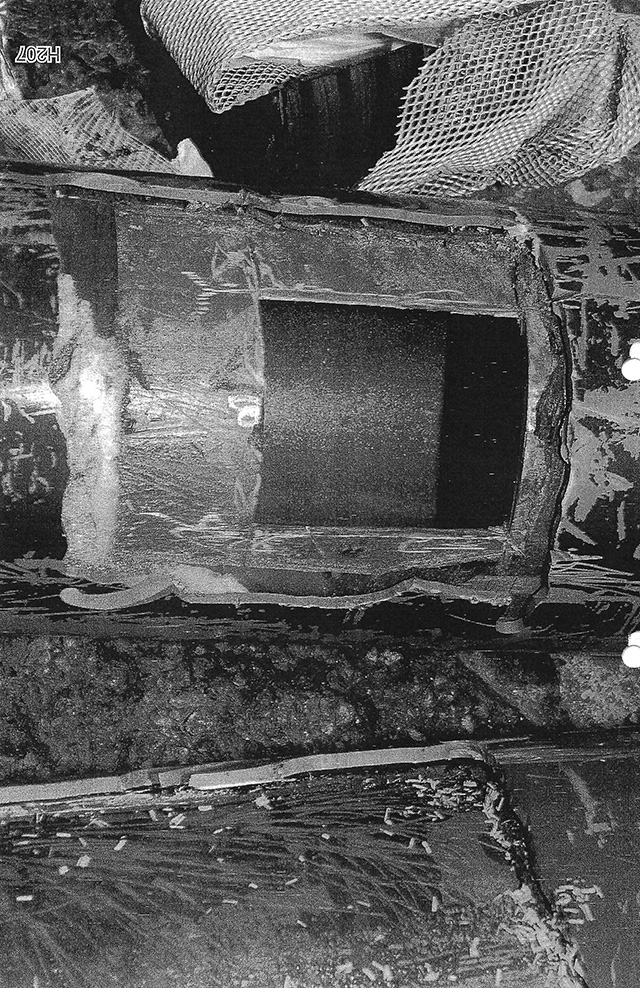

I finally started live streaming at 10:00 P.M to Facebook, giving the greenlight to our media team and the rest of the group supporting the action that we had done it: we had blocked the plane.

next...

VI. 2 A.M on the ground whilst sparks fly

19 By 2 A.M the pillow I was sitting on, on top of the tripod, had crumpled in on itself. My thighs were cramping and one of my shoes had fallen off. When practicing climbing that morning, I realised that the only way I would be able to pull myself up the tripod was to go barefoot. I had taken my shoes off in the van in anticipation and placed them in my backpack before we leapt out onto the curb to cut the fence. Running barefoot on wet grass was an unforgettable sensation, as was the feeling of bare metal between the soles of my feet, desperately gripping on to the surface of the scaffolding pole. By the time I pulled myself on top I didn’t have any strength left to tie my laces after I had slipped my shoes back on.

During the blockade, police officers repeatedly asked us: “What are you doing here?” and we told them, "We’re here to stop the deportation flight, there are people who are scheduled to be on board who fear for their lives". We spoke to them several times throughout the duration of the action hammering home the reason why we were there.

They repeatedly asked us to leave, but we didn’t. All of us had nappies on.

From the tripod, I had a clear view of the Inflite centre car park where the coaches were still parked. Fearful that the process would resume as soon as we were dragged off the ground I kept watch. The coaches finally drove off at 3 A.M. When the flight crew left at Midnight, we cheered as we watched them walk away, wheeling their cabin luggage behind them. When they began to drive the mobile staircases away, we started chanting “No Borders, No Nations, Stop Deportations”.

next...

Fig 25 and 26: Scans of police photographic evidence showing activists locked on, March 28 2017. Author: Unknown Date: March 28 2017

Fig 27: Video of the protest chants livestreamed from the direct action, March 28 2017. Author: Helen Brewer.

20 It took a long time for the police to cut and drag us out of our steel encased lock-on tubes. A testament to how diligent we were coating our pipes in tar and wrapping them in rubber, chicken wire and shards of glass and plastic. The tubes were so heavy we had to wheel them with us using trolleys. The layers of junk were a tactic for messing up the blades of a specialised cutting device used by emergency services. The trick was that every time the blade (shaped like a hand held circular saw) met a new material it would automatically stop to prevent itself from accidentally slicing into flesh. So there was a lot of waiting around and there was a lot of singing. Anything to keep our spirits up and shift our minds away from how uncomfortable our bodies were. As I found out later, it takes a great deal of stamina to lie on your back or on your front on the cold concrete for hours on end.

next...

Fig 28, 29, 30 and 31: Scans of police photographic evidence showing the lock-on tubes used. Author: Unknown, March 29 2017

21 I was the last to be arrested. While waiting for the police to figure out a suitable way to get me down, I watched airport cleaners sweep up below me. In an hour there would be nothing left except the plane, still parked on Stand 505. Finally, they used a smaller mobile staircase to edge near enough to the tripod and pull me off. I had been awake for 24 hrs and was frozen numb.

next...

Fig 32: Scan of police photographic evidence showing the empty tripod after everyone had been removed and arrested. Author: Unknown, March 29 2017

VII. The Judge suspected foul play

22 From the trumped up charges to the accusation of conspiracy, the series of events that would characterise the early stages of our case would have made Franz Kafka proud.

When we were arrested we were first charged with aggravated trespass and criminal damage. Sentencing normally carries a fine, community service or up to three months in prison. A few months later, the charge was changed to a terror-related legislation which falls under the Aviation and Maritime Security Act 1999. It was passed following the “Lockerbie Bombing” in 1998 and its maximum sentence carries life imprisonment.

I believe the State changed the charge for multiple reasons. First, the threat of life imprisonment was palpable. Our lawyers had no precedent to base our case on. Our precedents were either a minimum of 3 years (the sentencing a man who terrorised an airport watchtower with his helicopter got) to life. The threat was a heavy weight to carry for many members of the group. Added to it was a lengthy and expensive trial. Lives had to be put on hold just to deal with the impending case. People lost the capacity to carry on actions or organise around the campaign because all our energies had to be saved up for making it through the trial. Second, the government was fed up with people shutting down international airports and they were going to use this legislation against anyone who tried to break into airports again in the future - especially if they wanted to stop a deportation flight. The third and final obvious reason was - they were pissed off.

The first trial was originally set for March 2018 and lasted a total of two days. On the first day, the jury was selected, 12-16 people from the surrounding Essex constituencies. On the second day, we were called in to face the Judge who was concerned that our legal notes taken about jury members was in fact a ploy to conspire and possibly intimidate them. The Judge decided to dismiss the jury and pending a police investigation rescheduled the trial for October. Of course, the accusation was bogus and the investigation cleared us of any wrongdoing but the results had a crushing effect on our morale. The trial hadn’t even started and the Judge was already laying down the law and showing his bias. Devastated and shocked by the upheaval of the delay and the accusation, we quickly learnt and faced the harsh reality of the Kafka-esque judicial system.

Chelmsford Crown court can only be described as a cross between a concrete bunker and an office block from the 1970s. An unremarkable brutalist fortress of mahogany coloured bricks and oddly shaped protruding windows. During lunch breaks, jury members would stand and smoke under its muddy shadow looking bored.

Chelmsford Crown court looks exactly like it functions: tired, oppressive and inward-looking.

The location of the trial was an unfortunate geographical consequence of where the action took place. Essex is notoriously Conservative (and sometimes ultra conservative if you follow UKIP’s increased vote share in 2015). Following both 2017 and 2019’s General Election, all 18 Essex seats are and have been represented by the Conservative party. In the 2016 EU Referendum, all 14 District councils in Essex voted to Leave. It feels shameful to say, but having known this, the idea of trying a case of anti-deportation protestors in Conservative heartlands was a scary proposition to many - including our lawyers - who described the Essex court circuit as the backwaters.

But as we soon found out over the course of the trial, the heavy hand of state repression would in fact serve as a catalyst moment for the mobilisation of a massive national and international support base.

next...

VIII. Trial 2.0

(October 2018)

23 There’s a poster tacked onto the wall just outside courtroom 5. It shows first timers the configuration of the courtroom, who sits where, what happens and how you should behave.

The waiting room is a large windowless space filled with immovable rows of seats positioned in the middle. On the outskirts of the mass of seating are doors leading to private meeting rooms and entrances to the different courtrooms. There are monitors listing court times and cases and two vending machines. One sells watery coffee and hot chocolate and the other sells chocolate bars and packets of crisps. Every morning we would sit in the waiting room with our backpacks and Costa coffee cups in hand listening for our case to be called out over the P.A. Once it did, a steady stream of lawyers, defendants and supporters would march into the courtroom.

The waiting room would often be filled with familiar faces who came daily or weekly, but sometimes new people would respond to our call out. We made sure to fill the public gallery with people - an indication that the public was watching and on our side. We had Amnesty International observers report daily, forewarning the possible implications the trial would have on future protests.

Every day we entered courtroom 5, found our way to our cramped seats in the dock which was too small to hold all 15 of us and prepare ourselves for disciplining. Certain codes of practice and legal formalities became a new code of language to learn. We learnt how to stand up when told to and sit down and shut up for the most part. We watched and listened while our lawyers fought hard to defend our grounds and receive favourable judgement. But after a while, and especially over the course of ten weeks, the continuous match between the prosecution and the defence became another daily performance. We all felt restless and depressed when we lost submissions. There were plenty of moments when we would feel frustrated, angry, and distressed by what was happening, yet powerless to speak out but through our legal representative in quiet whispers.

next...

Fig 33: Scan of Stansted Airport map locating stand 505. Author: Unknown, Date unknown.

Fig 34: Scan of the Titan Airways charter plane dimensions. Author: Unknown, date unknown

24 It became a running joke in the dock, watching a jury member or someone in the public gallery fall asleep to the monotonous drone of the prosecution. The actions of the lawyers, the judge, the jury members and the court staff became so repetitive, we made a bingo game out of it.

Sometimes we’d have to have meetings in a tiny room next door, all 15 of us and our 10 lawyers in a 2 metre x 3 metre room. Lawyers would pull their wigs off and fan themselves from the lack of ventilation, there were too few seats, and most of us would have to sit on the floor. When important points in our case would come up, someone would peek through the tiny glass window in the door to make sure the prosecution weren’t in ear shot.

next...

IX.‘The Home Office on Trial’

25 Early on, the Judge and the prosecution were reluctant to include Home Office staff or the flight’s escort security staff as witnesses in our trial. This would have placed the spotlight on Home Office deportation practices and put staff in the line of fire for cross-examination by our Defence team. We argued that evidence of the abusive and violent nature of flights was a crucial reason as to why we took action. However, the Judge dismissed the submission citing the danger it would pose to deviating away from the core purpose of the trial: whether we “endangered the safe operation of the aerodrome”. We received two witness statements that were never made public in court from Immigration Enforcement. The first statement details the charter flight’s rationale made by the Home Office, explicitly citing the need to prevent last minute claims seeking judicial review that would disrupt the “complex” and costly operation. The second laid out the multiple contractual relationships between travel management companies who procure the charter flights and private escort security firms.

Despite the lack of witnesses, the Home Office was always present. A hired legal representative sat in court every single day watching from the gallery and recording the case.

It was sometimes hard to wrap your head around our case because it moved so far away from the issue of why we did it in the first place. Because of the charge, the trial centred on the health and safety of the airport and the people we supposedly put in danger by our action. The argument constantly made by the prosecution was to illustrate us as dangerous, reckless and thoughtless protestors. Anarchists (he wasn’t wrong) hell bent on causing chaos and disruption at the often quoted "fourth busiest airport in the UK”. They regularly cited the police having to down arm inside the airport in order to attend to our protest and flights having to be re-routed to other airports in order to land. The pilot of the charter flight described us as a dangerous mob of people in black running towards the plane, accusing us of potentially planting a device onto the plane. He said he couldn’t see, so his imagination ran wild. He was genuinely fearful, he told the court room.

next...

26 The “necessity defence” has often been used by activists and human rights campaigners to defend breaking the law in order to prevent imminent harm or death from occurring. The defence was key to explaining why it was necessary for us to break into Stansted that night and block the plane. Only seven out of the fifteen of us gave evidence at trial. But in all of our defence statements, we outlined our fears and concerns for the people due to be on the flight. Highlighting particular concerns for the people whose testimonies we read from Detained Voices. We also spoke about our fears of violence and assault to people whilst on the flight itself. We laid this knowledge out for the jury, referencing the history of immigration detention and deportation in the UK, personal relationships we had with people detained and deported, the many cases of documented mistreatment and abuse, as well as the many Parliamentary inquiries and independent reports condemning the practice. We pointed to Windrush, as the scandal had broken only months before in April 2018 and was still very much on the national public radar, and spoke about the Hostile Environment and the consistent failures of the State to protect people.

In the Judge’s final summing up of the evidence and before handing deliberation to the jury, he ruled that the necessity defences would not be left for the jury’s consideration. No reasons were given. He indicated that a reasoned ruling would follow at a later date. To date no reasons have been provided.

Two days after we stopped the plane preventing 57 people from being deported, a different plane was chartered with 23 people on board. The reason given was that they couldn’t find a big enough plane to charter. Out of the 57 people, 11 people remain in the country: 3 have leave to remain, 1 has been granted asylum and 2 have been granted residency permits as partners of European Economic area nationals.

For the rest of 2017, deportation flights to Nigeria and Ghana were moved to the Royal Airforce Base (RAF) Brize Norton in Oxfordshire, deporting 223 people on five different flights. Lisa Matthews from Right to Remain described the "ghost flights" as a response "to peaceful protest, the Home Office resorted to using the military to enforce the brutal policies of the Hostile Environment”(Miller, 2018). The move to RAF Brize Norton was a clear indicator of the steps the government were willing to take to ensure the deportation regime continued unhindered by resistance and disruption.

next...

X. The Verdict and Appeal

27 Less than a week after the jury went out to deliberate, we were found guilty of "intentional disruption of services at an aerodrome". We were sentenced on February 6 2019 and received 100 - 200 hours of community service and suspended sentences. The sentencing came as a surprise for many. Some saw it as a victory over State repression following mass mobilisation and press attention against the criminalisation of “peaceful” protest. It was a telling result. What it showed was an exercise in discipline - of its mostly white British citizens. The State didn’t need to make martyrs out of us - it had cemented the use of the legislation as precedent for future actions. It had wiped the use of the “necessity defence” off the table in protest cases after years of use in the climate movement.

The Judge in his conclusion, stated "The appellants should not have been prosecuted for the extremely serious offence under section 1(2)(b) of the 1990 Act because their conduct did not satisfy the various elements of the offence. There was, in truth, no case to answer." (March, 2021)

Two years later in January 2021, we won our Appeal against our convictions. We had submitted on 5 different grounds including the withdrawal of our necessity defence and the lack of disclosure from the Attorney General on his decision to change the charge. We won on our first ground which argued that the nature of legislation used to convict us was inappropriate for the action that we took. The Judge in his conclusion, stated "The appellants should not have been prosecuted for the extremely serious offence under section 1(2)(b) of the 1990 Act because their conduct did not satisfy the various elements of the offence. There was, in truth, no case to answer." (March, 2021)

next...

XI. Challenges

28 In some ways we did everything backwards. We did the action and then we tried to build a campaign to end deportations from it. The mobilisation was kick-started from the press and attention we received from our trial. The position the state put us in shone a light on an issue which would have otherwise been dampened by a lesser charge in Magistrates court.

The same day we were sentenced, a deportation charter flight to Jamaica (Taylor et al. 2019) left with 29 people on board. The Home Office’s reasoning stated that the people on board were "foreign national offenders" convicted of crimes in the UK.

An abolitionist position disputes this head on, but we failed to publicly state this. People who have already served their sentences should not be dealt a “double” punishment because of their nationality. Deportation doesn’t address the root cause of harm, instead it further compounds notions of migrant criminality and borders as mechanisms for control.

During our trial and subsequent appeal, we failed to publicly challenge the use of counter-terrorism law to convict not just us but the many communities who are subject to its mode of racialisation and non-belonging. We were able to play on the fact that we didn’t “look like your typical terrorist” - an image that continues to wreak havoc on families and communities in Britain and children outside, like Shamima Begum who, while pregnant in a refugee camp, was stripped of her citizenship. We also failed to call out the narrative that there were situations in which the legislation could be deemed "appropriate" use.

Action planning is fast paced, highly stressful, and relies on immense trust between people. A sense of urgency can often overtake meaningful dialogue that might mean slowing down. There usually isn’t time for everyone’s needs to be met or to address tensions or conflicts in the process. When everyone is working towards a goal, then the question remains to be asked, what gets left behind in the urgency?

The people who came together for our action didn’t necessarily share the same long term political visions or friendships. What we thought was going to be a fairly short in and out trial at Magistrates court was extended into a 4 year long legal battle that strained relationships. Had we anticipated the escalation of charges against protestors, which had been speculated about, and prepared for the possibility of a drawn out Crown court trial by jury, would we as a group have come together based on our initial temporal allegiances and on the solidarities that were urgently needed there and then?

next...

XII. Endless Possibilities

29 Movements, John Berger (2007: 2) writes, should never be reduced simply to the sense of what it achieves or fails to achieve. Our collective struggles for justice, for rights, for survival cannot be defined only by our demands, but rather through the co-constituted moments these movements enable. These moments, Berger continues, articulate “the countless personal choices, encounters, illuminations, sacrifices, new desires, griefs and, finally, memories, which the movement brought about.”

The mobilisation around our action and trial was immense and beyond any of our expectations. With the help of the Chelmsford Quakers, the local vicar and the local left wing community, we found families who opened up their homes to us. We found friends who supported us selflessly and generously. Without the support and solidarity we received from the Chelmsford community from day one of our trial, right up until our sentencing, we would never have been able to endure the toll it took. In many ways the solidarity demonstrations outside court and the Home Office showed us what a broad-church “no border” movement can look like, from church groups to trade unions, the Labour Party, radical climate groups such as Reclaim the Power and the many communities affected by the border regime.

The work is in building - building strong movements - not just mass movements - but strong communities and even stronger friendships. Something happens when we extend out our solidarities past insular identarian ways of working. When we resist with others and search for dignity in collective resistance. When we extend communication channels, share ideas and open up discussions. When we clarify our goals and our visions. That is the measure of resistance.

Because there is no blueprint for action. No straightforward route to revolution.

Freedom without action does not exist (Berger, 2007: 2) because only when taking action is freedom experienced, when the desire for change is so strong, it imagines endless possibilities.The intergenerational momentum that brings unmet demands to the fore is critical to building from histories otherwise forgotten. Our movements hold in its arms, the coming together of our shared desires, our fragmented connections, our tensions held against long distances, our protests, blockades and occupations that were defended and let go, the interpersonal relationships, dialogues, overrun meetings after meeting after meeting, conflicts, wins, and the many – many – losses. The nature of human spirit is the uncanny ability to always try, try again.

At the time of writing in May 2021, hundreds of Glasgow residents blocked an immigration enforcement van from detaining two men targeted in an early morning raid. The inspiring sight of a local community in solidarity with their neighbours is emblematic of the power of mass resistance. The men were subsequently released back into their community and residents were overheard saying, “when there is another raid in Glasgow, the same thing will happen again” (Brooks, 2021).

next...

Screenshot of the direct action that stopped an immigration raid in Glasgow. Accessed May 13 2021. Author: The Guardian Date: May 13 2021

References

30

Allison Eric and Hattenstone Simon, 2018, “Home Office contractors ‘cuffed detained migrants’ inside coach on fire”, The Guardian [Online], uploaded 21 February 2018, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/feb/21/home-office-contractors-cuffed-detained-migrants-inside-coach-on-fire

Berger John, 2007, Hold Everything Dear: Dispatches on Survival and Resistance., London and New York, Verso.

Brooks Libby, 2021, “Glasgow protesters rejoice as men freed after immigration van standoff” », The Guardian [Online], uploaded 13 May 2021, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/may/13/glasgow-residents-surround-and-block-immigration-van-from-leaving-street

Corporate Watch, 2018, “Deportation Charter Flights: Updated Report 2018”, Corporate Watch [Online], uploaded 02 July 2018, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://corporatewatch.org/deportation-charter-flights-updated-report-2018/

Ghadiali Ash and Grayson Debs (eds.), 2021, “Aviation strikes: Direct action at Heathrow, City and Stansted. A roundtable discussion with activists involved in aviation strikes”, Soundings, n° 78 : 172-188.

Hall Amy, 2017, “UK: How deportations are tearing families apart”, Al Jazeera [Online], uploaded 24 January 2017, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2017/1/24/uk-how-deportations-are-tearing-families-apart

HM Chief Inspector of Prisons, 2015, Detainees under escort: Inspection of escort and removals to Nigeria and Ghana., London, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Prisons.

March Samuel, 2021, “’No case to answer’ — Stansted 15 convictions quashed by Court of Appeal”, UK Human Rights Blog [Online], uploaded 29 January 2015, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://ukhumanrightsblog.com/2021/01/29/no-case-to-answer-stansted-15-convictions-quashed-by-court-of-appeal/

Miller Phil, 2014, “Majestic deportations?”, Institute of Race Relations Blog [Online], uploaded April 10 2014, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://irr.org.uk/article/majestic-deportations/

Miller Phil, 2018 “Hostile Environment: Home Office now using military base for deportation flights”, JOE [Online], uploaded November 2 2018, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://www.joe.co.uk/news/hostile-environment-brize-norton-deportation-204714

Miller Phil, Stop Deportation, Youssef Shiar and Corportate Watch, 2013, Collective Expulsion: The case against Britain’s mass deportation charter flights., London, Corporate Watch Co-operative Ltd.

Taylor Diane, Gentleman Amelia and Davis Nick, 2019, “Deportation flight lands in Jamaica after reprieve for some”, The Guardian [Online], uploaded 7 February 2021, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/feb/06/jamaican-detainees-last-minute-deportation-reprieve-home-office-flight

Taylor Matthew and Booth Robert, 2014, “G4S guards found not guilty of manslaughter of Jimmy Mubenga”, The Guardian [Online], uploaded 16 December 2014, accessed 15 May 2021. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/dec/16/g4s-guards-found-not-guilty-manslaughter-jimmy-mubenga

next...

Notes

31

1 See Lesbians and Gays Support the Migrants campaign against British Airways and SOAS Detainee Support campaign against TUI.

2 https://www.federationifir.com/en/

3 https://righttoremain.org.uk/campaigners-blockade-heathrow-detention-centres-to-stop-iraq-deportation-flight/

4 https://www.indymedia.org.uk/en/2009/05/430420.html

5 https://network23.org/antiraids/2015/03/10/coach-blockade-to-stop-mass-deportation-to-afghanistan/

6 https://www.planestupid.com/

7 http://www.lgsmigrants.com/

8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FmrQtUR_-Is

9 https://soundcloud.com/detained-voices/statement-charterflight-28th-march

10 https://detainedvoices.com/2017/03/28/now-they-give-me-another-charter-flight-ticket-they-give-me-a-ticket-for-28th-now/

11 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1990/31

12 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan_Am_Flight_103

13 https://electionresults.parliament.uk/election/2019-12-12/results/Location/County/Essex

14 https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/stansted-15-verdict-crushing-blow-human-rights-uk

15 https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/616096/response/1614825/attach/html/3/59407%20Strickland.pdf.html

Return to the beginning of article...

https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/antiatlas-journal-05-brewer-how-to-stop-a-deportation-flight.pdf