antiAtlas #5 – 2022

“Action Black Autumn”: The Genesis of Air Deportation in Switzerland, 1985

Marianne Büttiker, Friederike Kretzen and Barbara Lüthi

Summary: In 1985, Zairean migrants were deported from Switzerland in what was presumably the first mass deportation on a charter flight titled “Action Black Autumn”. In collaborative work between a historian, artist and writer, the article aims to approach this deportation flight from different angles and situates it historically between Switzerland’s colonial entanglements and increasing restrictive immigration policies since the 1980s.

Marianne Büttiker, lives and works in Basel and en route. After studies at the Basel School of Design, she worked for many years as a freelance textile designer and art mediator; today the visual artist lives and works where art draws her. Past and present projects are “archive of sounds - places and their colors, 2007 – 2017” and "Senda d'aua", the mineral springs in the Engadine window, a research work on the 25 mineral healing springs in the Lower Engadine and its continuation since 2020 titled: “Memory and memory sources and essences”.

Friederike Kretzen, born in Leverkusen, studied sociology, worked as a dramaturg in Munich. Writer, author of numerous novels. Literary critic, essayist, lecturer at Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (Zurich), at Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK), and at Bern University of Applied Sciences (BFH). Last publication: "Schule der Indienfahrer". Work in progress „Persienroman“.

Barbara Lüthi, historian, Senior Researcher and PD Dr. in North American and European History, Postcolonial Studies, Global History and the History of Social Movements at the University of Leipzig, Germany. Her books include Postcolonial Switzerland (co-authored with Patricia Purtschert and Francesca Falk, 2013, 2nd edition). She just completed a book entitled "The Freedom Riders Across Borders: Contentious Mobilities" (Routledge).

This collaboration between an artist, a writer and an historian represents a “choral” mode of writing in which multiple voices and images are woven together and form a polyphonic text.

All photos are Marianne Büttiker's.

Keywords: “Action Black Autumn” air deportation, Switzerland, Zaire, art, literature, history

antiAtlas Journal #5 "Air Deportation"

Directed by: William Walters, Clara Lecadet and Cédric Parizot

Design: Thierry Fournier

Editorial office: Maxime Maréchal

antiAtlas Journal

Director of the Publication: Jean Cristofol

Editorial Director: Cédric Parizot

Artistic direction: Thierry Fournier

Editorial Committee: Jean Cristofol, Thierry Fournier, Anna Guilló, Cédric Parizot, Manoël Penicaud

To quote this article : Lüthi Barbara, Kretzen Friederike, Büttiker Marianne, "'Action Black Autumn': The Genesis of Air Deportation in Switzerland, 1985", published on June 1st, 2022, antiAtlas #5 | 2022, online, URL: www.antiatlas-journal.net/05-

I. Where do they fly, the airplanes?

1 The word deportation to me, born shortly after the war in Germany, is associated with deep fears. Fears that I shared with my parents, neighbors, the streets and fields. Fears that lurked in kindergartens, sat at the desks in schools and taught me to write. To this day the word frightens me. As I got older, at the time of the uprising in the 1960s/70s (Kretzen, 2018), I was sure that this word would never be used again. It was the word abused beyond the masses, the ultimate word of abuse.

It was the word abused beyond the masses, the ultimate word of abuse

I couldn’t imagine that it ever would come off your lips again so simple and easy. As if it were nothing but the word of a function that protects us from what comes from outside.

next...

In flight. An airplane doesn't read the newspaper, it doesn't know what it's doing. It buzzes, is big, flies over all warning lights through the heights of memorylessness. What a sky, what width, how high the air. Where the blue moments emerge, the transitions from space to light. And as if mad it dreams to embrace the sky. To connect times, countries and seas, and rather be wrong than let others decide. The aircraft does not hold its course, leaves its route, and turns back. It brings the birds back. Even the odd ones. Which we miss.

2 Where do they fly, whereto? What are the pilots doing, the stewardesses, what are they dreaming? Who are they? And the sky, the early morning when they all take off together? Leaving behind the halls and corridors of the airport, the inspectors and security officers. The watches, the staff in the canteens, the products in the duty-free shop. A thousand bottles of whisky. Everyone participates, is there, pretending they are air. Who gives the orders? What do they listen to when people in shackles are taken by law into the dark forest as in the fairy tale Hansel and Gretel?

next...

3 Countries and their little goats. Countries are not airplanes. They don’t set out, don’t rise, don’t leave. They want to remain, secure borders, lock everything. They are not looking for adventures, do not have such a spirit of adventure either, stay on the ground, insist on law, order and facts. Difficult are only the transitions, doors and windows. What can go in, what has to go out? The enemy outside, the friend inside? The mother or the wolf? Eat a little chalk, paint the paw white, and one looks like the other. And he is already in. Like in the fairy tale of the Seven Goatlings. Why? Didn’t the mother, before she went out, warn them?

Didn’t the mother, before she went out, warn them?

How could that happen? Maybe because there are certain similarities, agreements, between mother and wolf. Maybe because life is about mixes, about many things at once, and not one without the other. Nobody is just particular. No one just strange or not belonging. There crouches the age-old danger of being mistaken. No country escapes her, that wants to put an end to the disorder, the ambiguous and unrelated. A danger that can only be met with openness.

But instead of opening the doors, also those of decisions and orders, we – the Seven Goatlings – work out of sheer fear on strengthening the wolf. To which we give our own traits, so that he only becomes more and more like our mother. Until the land has become wolf from top to bottom. And we deport the mother on the plane. With her the relation to our vulnerability, the powerlessness and dependency through which we were born. We are what we deport.

next...

"What is particular about the violence of men is that if silenced, especially if silenced, the violence spreads to the next generations." Julia Kristeva, Micropolitique, Paris: Editions de l’Aube, 2001, p. 51.

II. Fragile in/visibility

4 The case “Action Black Autumn”: On October 15, 1985 the head of department of the Federal Police Office sends the following request to the Political Department of the Federal Department for Foreign Affairs on behalf of Federal Councilor Elisabeth Kopp: “The action against the approximately 50 from Zaire, who have sought asylum illegally, will start on November 1, 1985 with the arrest of the people in question. There is the political will to transfer these foreigners to Kinshasa immediately with a charter flight under police escort. We are currently busy trying to win a domestic or foreign airline for this flight”. This marks the beginning of a long-term action with the name “Action Black Autumn” which a few weeks later resulted in the deportation from Switzerland of over 50 men and women from what was then Zaire. Several weeks pass from arrest for forgery of documents and thus a violation of the Asylum Act, over the internment to the actual deportation. During this time, reflecting an extensive apparatus of capture, the people in hiding must be located in the various cantons, travel documents prepared, translators and escorts as well as various transports organized. From the preparations to the aftermath, a myriad of actors are involved in this deportation: In addition to the deportees, for example, the Federal Department of Justice and Police, the cantonal police, lawyers, doctors, aircraft personnel, politicians, diplomats, NGOs as well as national and international media. According to eyewitness reports, the Zairians offer considerable resistance during their deportation on November 3, 1985. In a following request for a parliamentary investigation by the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland, it says: The “black autumn” had “turned into a downright deportation. The Ticino and Zurich police had behaved brutally”, so that the Zairean authorities summoned the Swiss ambassadors in Kinshasa to “protest against the method of deportation”. The media write that the deportation was carried out like a “cattle transport”.

The media write that the deportation was carried out like a “cattle transport”.

While the Federal Police Office rejects the allegations of police violence, it also refers to the special circumstance, “that they were neither refugees nor asylum seekers [...], but undesirable foreigners who had tried to get asylum under a false identity”. The commander of the Zurich canton police wrote a letter to the doctors involved: “This deportation transport was also a novelty for us, and we are in the process of systematically evaluating the experiences we have made and are recording this in writing as a basis for any later deployments of a similar type. Your recommendations from a medical point of view are therefore very valuable to us and will be included in the evaluation documentation mentioned. I am happy to take the opportunity to thank you once again for your willingness to accompany this deportation flight. Actions of this kind always have many burdensome aspects for us, and no police officer takes part in them with pleasure. For us, however, this is simply a legal duty from which no one can escape.”

next...

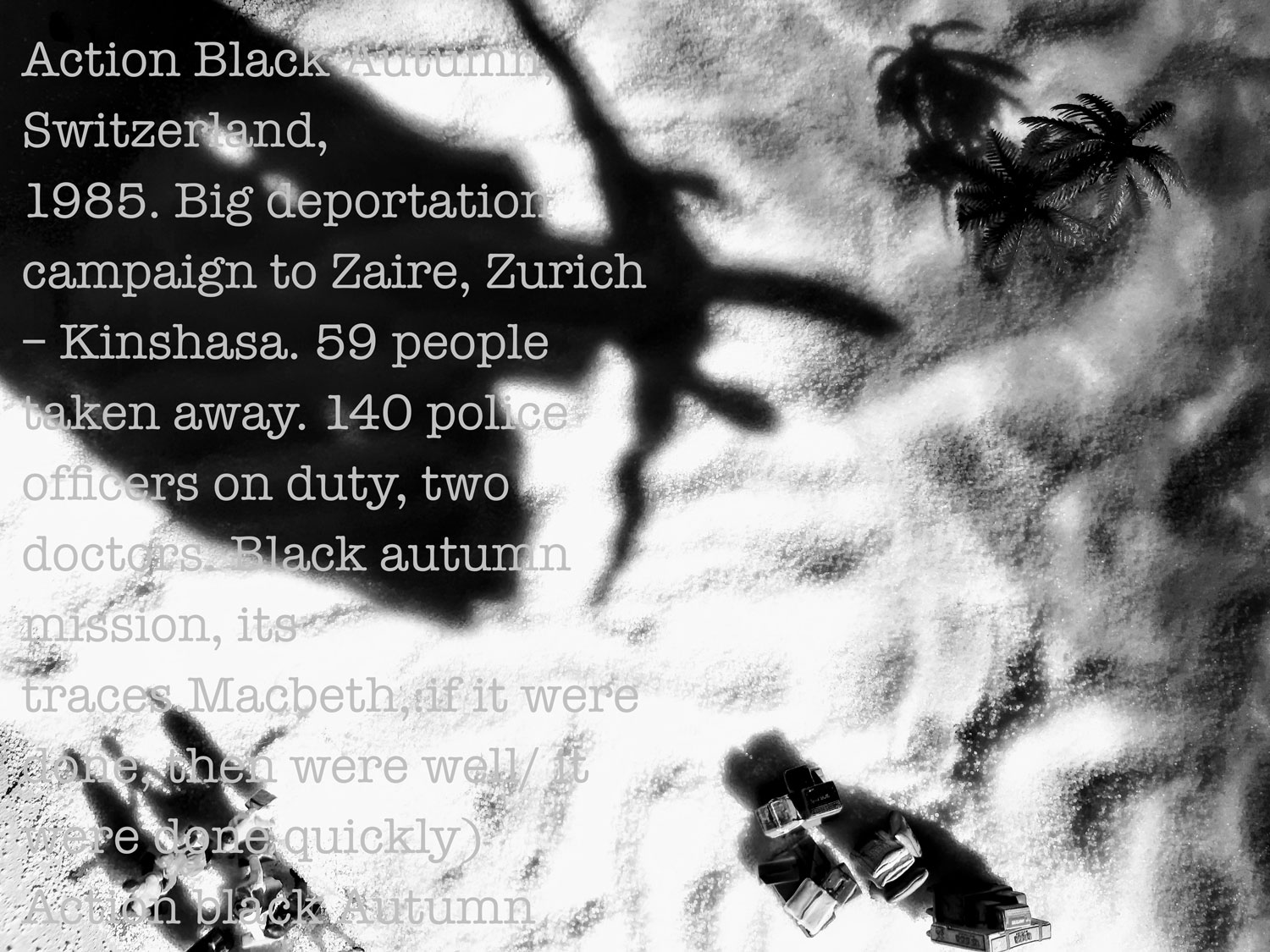

Action Black Autumn, Switzerland, 1985. Big deportation campaign to Zaire, Zurich – Kinshasa. 59 people taken away. 140 police officers on duty, two doctors. Black autumn mission, its traces. Macbeth,: ‘If it were done when’ tis done, then ’twere well / It were done quickly') Action black Autumn action

5 “....and no police officer takes part in it with pleasure.” Black autumn of Switzerland.

The doctors and police officers are thanked for their commitment from the very top. Which, the police chief particularly points out, they did not execute with joy. Freud writes that the problem is not murder, but its traces. (He got that from Macbeth, who desires nothing more than: ‘If it were done when’ tis done, then ’twere well / It were done quickly’).

The problem is not murder, but its traces

If a police chief, in defense of his police officers and law enforcement officers, points out that they did not enjoy their mission, it can be assumed that there was joy in the game. The chief of police would surely ask me how I come up with this, this was an immoderate allegation. But as someone who works with language, who tries to listen carefully to her silence, this reaction is familiar to me since school, where my German teacher wrote under almost every poem interpretation: overinterpreted. A term that for me has since been an indicator that it is about traces that should not be seen.

next...

6 Deportations from Switzerland were not a new phenomenon at the time. The legally enshrined “deportations of the poor”, for example, in which foreign persons became a burden to public poor relief, had, especially since the beginning of the 20th century, with the “nationalization of the social” (Gérard Noiriel), deported people from Swiss territory (Matter, 2014). Different variations of "expulsions" unfolded over the decades, which repeatedly affected new target groups: For example, the so-called “vagabonds” and “Romanichas” at the turn of the century and especially Jewish people during World War Two (Gadient, 2019).

The authorities justified their secrecy with the risk that those affected could go into hiding

What was new in the 1980s is the first deployment of a charter flight. But the fact that the “Aktion Schwarzer Herbst” even came to light is mainly due to a coincidence: If you believe the tabloid Blick, a journalist from French-speaking Switzerland happens to find out about the deportation and gets information from the authorities. Further information that we have about the course of this deportation comes from the flight crew involved in the deportation. Only afterwards did the Federal Department of Justice and Police communicate and justify the deportation in a press release. In the case of the Zairians, the authorities justified their secrecy with the risk that those affected could go into hiding: “The action requires careful preparation and must be treated with the greatest discretion”, they wrote before the action was carried out. In the aftermath of the deportation, Blick wrote that both the press spokesman and the cantonal police involved in the deportation "tried to surround the 'Black Autumn Campaign' with the greatest possible secret from the start”. Almost all deportation flights only become public by chance during this time. In another event from the time, the deportation of two Zairian refugees from Lucerne, tranquilizers were used. The case reached the media again only by chance: The medical officer had sent the bill to the wrong address.

Thinking about deportation in terms of regimes of visibility, it is important to acknowledge that there are different visibilities at play here: Whereas the state tries to conceal the deportation act, it only becomes public by mistake. Only then does the media, human rights groups and politicians step in to create another layer of visibility.

next...

7 Media spectacle. Shortly after they were deported, the German weekly “Der Spiegel” wrote that the deportees were shackled and treated brutally. A few weeks after the “action”, the journalist of the weekly “Weltwoche”, Peter Hartmann, follows the “traces of the 59 Zaire refugees” and flies with other media people at the invitation of President Mobutu to Zaire “to count the number of refugees who have returned, of which, according to a ‘La Suisse’ headline, six should be lying dead in the cold rooms of the Mamayemo hospital.” In his article (title: “How Mobutu teaches the little Swiss to count”) he describes the “demonstration” of the deportees: “In the large ‘Voix de Zaire’ television studio, the spotlights fall on a group of silent, quietly sitting people who left Switzerland on November 3rd, handcuffed.” Several people report about their experiences in front of the camera: Minister Ramazzani rants against the “shameful campaign against Zaire” carried out by Switzerland; the Belgian chief doctor Jean Seghers from the Mamayemo Hospital reports that “15 people received outpatient care immediately after arrival because they had injuries inflicted on them by Swiss police officers“ (Hartmann, 1985). In gigantic circling spotlights the Zairian TV camera creates a luminous glare revealing the deportation story to the whole world. Do such media reports entail the production of a kind of counter-visibility?

”On what grounds can we assume that violence occurs always at the surface, that its effects are always visible?”

As William Walters argues, in “the absence of such campaigns, there would only be numbers, targets, cases, statistics. But in the public space generated by petitions, demonstrations (…), the deportee becomes a person, a face, a human life” (Walters, 2018: 35). Still, we must ask ourselves in relation to deportations and visibility: ”On what grounds can we assume that violence occurs always at the surface, that its effects are always visible?” (Winter, 2012: 196). The injuries on the bodies and heart often stay invisible, leaving traces only for the deportees. And seldomly leaving faint traces in the sources for scholars to decipher.

next...

III. Protest and their violent traces

8 Deported life. Life as deportation. Development since 1985 until today – Have we, the western, the rich countries, made space, its stations, its orbits, its safe routes into an endless ramp of selection? Where we stand, still speechless, without a word, senseless, uncertain whether we will ever have existed. So that only the dead know whether their deportation is ever over.

So that only the dead know whether their deportation is ever over.

A boundless accelerated mobility has firmly taken hold of the sky, distance and time. It imposes a rhythm on us that seems to make any delay, any hesitation, impossible. A rhythm that causes us to fall out of our references, to drift around placeless and aimless. Ready to follow all instructions without question. What we call tourism has long since become a form of deportation in its global expansion. Like people, countries, skies, cities and seas are deported (Kretzen, 2019).

next...

9 “Deportees shall be treated with the same courtesy and tact as all passengers” (Swissair).

Alessandro Spena has highlighted three main forms of resistance in restricted spaces such as immigration detention or deportation procedures: First, institutionalized resistance using institutional paths purposely designed by law; second, anti-institutionalized resistance performed through actions prohibited by existing laws and therefore generally classified, by both public authorities and public opinion, as forms of ‘criminality’, ‘violence’ and ‘vandalism’ (such as riots and turmoil); and third, non-institutional resistance through actions that neither are prescribed as “canonical legal remedies”, nor are contrary to law (such as self-hurting) (Spena, 2016).

Scholarship within Deportation Studies has pointed to the limits of deportation, the interruptions and disruptions intervening in the supposedly “well-oiled machine” of the deportation regime. Deportations happens not just at the level of international politics, or bureaucracies, but also take hold of the bodies, feelings, and souls of the deportees themselves. The threat of deportation has triggered a genealogy of acts of protest: hunger strikes, suicides, self-harm… These can be read as political acts of confronting state justifications for removal (Drotbohm, 2013). They also highlight the – mostly very limited – political agency of deportable populations. But what kind of resistance is possible in an isolated chartered deportation airplane shut off from public attention? The archival files of the “Action Black Autumn” contain fragmentary traces of violent resistance.

The archival files of the “Action Black Autumn” contain fragmentary traces of violent resistance.

The turbulences at the beginning of the flight testify to the physical and emotional upheaval of the deportees. As the doctors mention in their report, 3 policemen had bite wounds on their hands and forearms; and “another man with an apparently quite painful left wrist (caused by impetuous behavior in handcuffs), we fixed his forearm and wrist and gave him a painkiller.” Another report speaks of a policeman with “a broken arm”, and newspapers and official reports write of screaming and “violent clashes” between the Zairian deportees and the police – unmistakable signs that the Zairian migrants were being deported against their will and that they fought back with hands, feet and teeth, leaving visible traces on their bodies.

next...

10 In some cases the deportees themselves or migrant communities manage to articulate and activate social protest and resistance, and claim the state’s protection for populations threatened by deportation. The “Action Black Autumn” even draws international protest: In front of the Swiss embassy in Stockholm, for example, Zairean citizens demonstrate against the deportation. Scholars have pointed out that the labelling and removal of a given category of foreigners does not necessarily forge cohesion within deporting societies at large. Contentious conflicts can occur among citizens, and between citizens and state authorities, over who is eligible for state protection and who is not. Many anti-deportation campaigns draw on human rights discourses by highlighting the vulnerability, innocence, and need of protection of deportable populations. Sometimes they manage to raise public awareness and to rehumanize the figure of the deportee (Drotbohm, 2013; Inda, 2011).

The list of accusations against the Swiss government and its “action” is long. The “League for Human Rights”, which documents and organizes protests and petitions on human rights abuses, voices serious allegations against the head of the Justice and Police Department and the Federal Police Office (BAP) after the incident: “A dossier presented to the press on Friday alleged that the BAP was unable to make detailed inquiries about asylum seekers. Based on our own research on the recently deported 59 Zairians, the league wants to prove that both the embassy in Kinshasa and the BAP have made serious mistakes. In its dossier, it demands that the Federal Council take a position on the allegations, no longer repatriate rejected asylum seekers as long as there are uncertainties and that the investigations are not only carried out correctly, but also in cooperation with humanitarian organizations.” Others argue that despite president Mobutu’s will to “perform” the 59 Zairian deportees on TV, this was no assurance against their death threat in the aftermath of their official public presentation, as it was known that torture was common in Zaire. “In previous actions, the President had also carried out such demonstrations, but then had those affected killed after they were presented.” The “Asylum Committee” argues that the “Black Autumn Campaign” jeopardized Switzerland's reputation as a humanitarian country.

The “Asylum Committee” argues that the “Black Autumn Campaign” jeopardized Switzerland's reputation as a humanitarian country.

The "repatriation" not only disregarded the right of asylum, but also the prohibition of torture. The substance of Swiss asylum law is crumbling, asylum seekers are treated inhumanely (...) and a short-sighted opportunism can no longer be overlooked by the authorities. ” The speaker of the “Coordination Committee of the Zairian Opposition”, Mathieu Musey, voices the most bitter critique. Himself a political opponent in Zaire, shortly after the “Action Black Autumn” he is deported in a helicopter first to the military airport in Payerne and from there in a private jet to Kinshasa. At that point he has already been living in Switzerland for 15 years before his claim for asylum is rejected. His case turns into one of the most famous and spectacular deportation cases in Swiss history. In the context of the “Action Black Autumn” Musey asks, “why the mass deportation was tested on Africans of all people. The former black slaves have now been used as guinea pigs. ” In the following press conference the fear of further concerted mass actions is voiced: “In Geneva, for example, actual raids are being carried out on black people.”

next...

11 Names call each other like birds call each other. Black autumn, German autumn (Deutscher Herbst). 1977. The Red Army Faction (RAF) terrorists Bader, Meinhof, Enslin found dead in their cells. After the failed hijacking of a Lufthansa plane to Mogadishu, followed by the murder of Hans-Martin Schleyer.

I was 21, emotionally troubled and confused. Firmly convinced that the RAF members were murdered. For weeks there were raids in friends' communes, mostly at night or early in the morning. Houses were surrounded. Cars stopped on the highways, police officers with machine guns in front of whom we had to line up. I was afraid of Germany in Germany. With this fear I was born into this land. The traces of the Holocaust, the annihilations of the war were palpable everywhere. The more they were denied, the stronger.

Everything that cannot be said, that remains denied, comes back, haunts us, stands in the hallway, waits for us. It dies, is forgotten, but it does not go away. When I was afraid as a child, dreamed of the war, the adults said that it was the fear of the dark, all children had that.

Who weeps for those who have been carried away?

Out of this darkness the names call themselves. German autumn and black autumn in Switzerland. The heart of an unspeakable horror beats there, a wound that still not has found its language, and impossible grief. Who weeps for those who have been carried away? Their disappearance in the belly of the big birds. The grave in the air.

next...

Names call each other

IV. Colonial entanglements

12 The figure of the “migrant slave” and the frequent comparison and evocation of the Zairian deportees as “guinea pigs” and animals, leads to the question of what the formation of the deportation regimes in Switzerland has to do with colonialism and colonial history.

How can the forms and effects of the colonial regimes in a country like Switzerland be understood? And what do deportations have to do with it? (Purtschert, Falk, Lüthi, 2015; Purtschert, Lüthi, Falk, 2013). It is important to scrutinize the often depoliticized and dehistoricized ways in which contemporary migrations and deportations have come to be associated with imaginaries of the trans-Atlantic slave trade by putting the stories back into their context.

In the context of the emergence of the deportation regime, the "Action Black Autumn" in Switzerland has to be understood against the background of changes at the legal and discursive level in the immigration policy in the first half of the 20th century and the asylum policy of the post-war period. First, as a result of the world economic crisis of 1973, new processes of negotiation of immigration policy took place, which represented the transition to a more restrictive quota policy. Second, this process was largely supported by economic interest groups, but above all by right-wing authoritarian nationalist movements and parties. Most political parties in Switzerland responded preventively to their demands by complying with more stringent asylum laws (Skenderovic and D’Amato, 2008). Thirdly, the changes were also responses to the change in transnational mobility movements and the increasing number of asylum seekers, whose diversity of origin was presented as a new challenge. The arrival of the new asylum seekers led to a change in the “moral economy” (Didier Fassin) within Swiss society. In Switzerland after the Second World War, still in view of the shocks of the Holocaust, “respect” for the arriving communist refugees was one of the accepted moral sentiments. This also correlated with practical considerations of labor demand. These sentiments changed in the late 1970s with the arrival of asylum seekers from the Global South who fled poverty, drought and war.

How can the forms and effects of the colonial regimes in a country like Switzerland be understood? And what do deportations have to do with it?

As William Walters argues, racialization and foreignness are elements “that have historically served to make deportation seem not at all extraordinary, despite the violence it entails, but on the contrary quite acceptable to significant sections of the public” (Walters, 2018: 35). It is during those years that the incoming migrants are divided into “true” and “false refugees”. Accordingly one of the key roles of deportation is set in motion: to distinguish (potential) citizens from noncitizens – and thereby solidifying an exclusionary social inequality for an indefinite future by defining who has the right to stay and who the need to go.

next...

13 Such deportations must also be understood in the context of colonial history and Switzerland's deeply rooted relationships with countries in the Global South. Zaire is a paradigmatic example (Perrenoud 2018): While the Democratic Republic of the Congo (from 1971–1997 “Zaire”) was under Belgian colonial rule until 1960, the colonization under King Leopold II (1865–1909) was also supported by Swiss officers, administrators and traders who were also involved in the slave trade (David, Bouda and Schaufelbuehl, 2005). Between 1773 and 1830, Swiss people were directly involved in almost a hundred expeditions in which around 20,000 people were forcefully shipped across oceans. At the same time, ecclesiastical and intellectual circles, especially from French-speaking Switzerland, got involved against slavery. In the second half of the 19th century there was also an anti-slavery movement in Switzerland. Between 1877 and 1898, various societies emerged that committed themselves to combating the slave trade by Muslims within Africa and the Middle East. The social milieu in which these associations thrived was liberal conservatism, which is closely linked to the evangelical revival movement and which promoted the project of a religious and moral renewal of society through a wide variety of organizations. Africa represented an “imagined space” onto which the conflicts within the Confederation could be projected. Also, a committee to support geographical exploration of Africa was established during this period. In 1876, the Belgian King Leopold II organized a conference of national geographical societies in Brussels, which, following the expeditions of David Livingstone and Henri Morton Stanley, planned further research trips to Central Africa in order to gain further knowledge for later colonization. The “Association Internationale Africaine” founded at this conference opened sections in various countries, including the “Comité national suisse pour l’exploration et la civilization de l’Afrique centrale” in Switzerland in 1877. They raised money for further research expeditions. After the Berlin Congo Conference, which awarded the Congo Basin to the Belgian king, the section dissolved in 1885. However, the end of colonization did not mean the end of Swiss relations with the Congo. In the interwar period, and especially after 1945, economic and financial relations with the Belgian Congo intensified through the sale of technical equipment, chemical products, textiles and other materials. Conversely, Switzerland obtained a wide variety of raw materials. In parallel to economic relations and investments, there was a movement of migration in both directions. In addition to Zairean students, the first refugees came shortly after the independence of the Congo in 1960, who for a long time represented the largest group of African refugees in Switzerland. But the memories of these entanglements and shared histories dating back to the colonial era were completely lost during the formation of the deportation regimes in Western Europe. Here we see a historical resonance between the slave trade and the deportations.

Here we see a historical resonance between the slave trade and the deportations.

Not inanimate cargo, many enslaved Africans resisted their coerced transatlantic journey, just like many deportees resisted their coerced transnational flights. Remembering Switzerland’s past and bringing them into the context of more contemporary migrations and deportations reminds us, how the geographical trajectories and the people traveling these paths were reversed. Over the centuries Switzerland transformed from being an outgoing labor migration country to being a migrant destination while simultaneously evolving as a deportation nation.

next...

V. The seemingly smooth execution of deportation: infrastructure and logistics

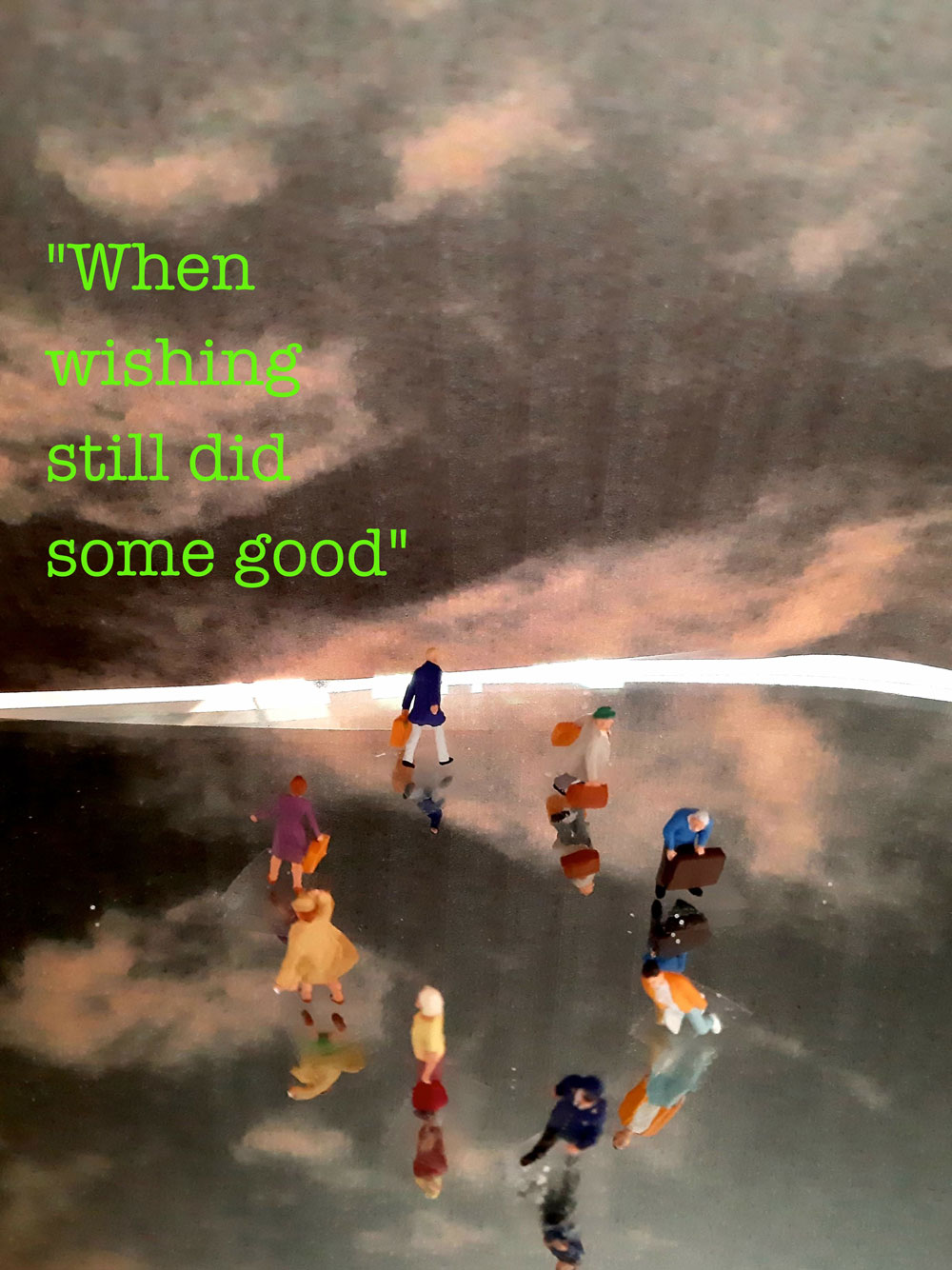

14 When wishing still helped. When wishing still did some good. There is cruelty, it is part of life. Defying it, resisting it, is just as much a part of it. Resistance is hope, says René Char. With every plane in which people are taken away against their will and by law, we lose our hope of avoiding the cruelty. We become even more cruel and more hopeless.

We live in times of execution. Smoothly. Well-lubricated machinery, almost gapless. Execution is another word for mercilessness. Because grace can only enter through gaps.

Because grace can only enter through gaps.

But they are sealed off like the borders of our western countries. In the times when wishing still helped, when wishing still did some good, of which the fairy tales speak, there were postponements, disobedience to commands, unexpected coincidences that seem as nonsensical as they are happy.

Fairy tales come from the time when wishing still helped. At least it could move mountains. They know that in the midst of greatest need the middle way is death. From there come the unexpected twists and turns, the lucky coincidences that are the engine of fairy tales and wishes. We have sealed off our countries as safe zones for a desireless disaster. In addition to the mother, they are also missing the wolf: hardly any sensation at home.

next...

"When wishing still did some good"

15 Forced mobility does not just entail a move from A to B, it is not a line between two places. It involves an army of bureaucrats, medical and judicial experts, police forces, vehicles, identity papers and documents – and even more. Deportations are dependent on technologies, technical structures, institutions, and human beings to make coerced movement possible in the first place. But these factors are also vulnerable to destabilizing processes. Disruptions of the seemingly frictionless functionality of the Blackbox “infrastructure” manifest themselves in moments of failure or obstruction.

Disruptions of the seemingly frictionless functionality of the Blackbox “infrastructure” manifest themselves in moments of failure or obstruction.

In the case of the “Action Black autumn” moments of disruption and delay briefly erupted in the chaotic logistic coordination between the cantons; in interventions of journalists and solidarity groups; or when the deportees physically resisted their deportations.

next...

16 A letter from the medical staff (an anaesthetist and the head of the airport ambulance in Zurich, who are responsible for medical support) is titled:

“Mission to Zaire on November 3, 1985: Repatriation of 57 Africans, escorted by 114 Swiss police officers, an emergency doctor and a paramedic (IVR), from Zurich to Kinshasa with a Swissair DC-10.”

The two doctors bundle their information in a report to the Commander of the Cantonal Police in Zurich for the possible preparation of future operation guidelines and actions based on this first experience. In details they describe their preparation for the flight: “We equipped ourselves in such a way that we could have transported several people suddenly ill or injured in the event of violent actions with efficient assistance, i.e. in extreme cases with secured vital functions and with adequate pain relief and sedation to the next responsible hospital. Both the tendency of the people to be brought home to violent actions and the ‘reserve material’ brought by the police to safeguard the situation clearly showed during the operation that we had made our (short) preparations on the basis of realistic notions».

In detail they describe their medical assistance in the airplane during the deportation: 3 police officers had bite wounds on their forearms and hands. On the part of the deportees two had skin irritations and one «with alleged headache from a bruise with abrasion on the right forehead, which, as he confirmed, was more than 24 hours old. (...) We were able to alleviate the 'bobos' of all three with targeted measures and above all with dosed goodwill.» Further they describe their «medical material concept» which contains diverse «medical equipment» such as resuscitators, different kind of bandages, a suitcase including amongst others 50 injection syringes, and medication such as valium ampoules usually used for sedation, Atropine normally used for cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

The descriptions are condescending: The deportees are described as renitent, their «alleged» pains constantly put in question and infantilized by describing them as minor «boo-boos». But more importantly, this rare and detailed example of an early deportation flight in Switzerland shows how from the start healthcare professionals were involved in the biopolitical management of migrants’ mobility and were part of «smoothing its eliminative function» (Blue, 2019: 102). Whereas one could argue that their presence on sites of detention and deportation was necessary to ensure the deportees access to medical care, their role risked being instrumentalized to ensure the sustainability of detention and swiftness of deportations. They became part of the power invested in policing deportations. This single deportation flight entailed 114 policemen and medical staff to ensure the efficiency of this form of regulation and disciplining.

next...

VI. What remains?

17 «1 SAC SAMSONITE AVEC 8 PANTALON CUIR + 4 BLOUSON CUIR AVEC 1 VESTE BLANCHE AVEC 8 CENTURE AVEC 4 PANTALON TISSUT

1 VALISE AVEC 4 PAIRE DES CHAUSSURE 1 BLOUSON BLANCHE 1 BLOUSON NOIRE 5 PANTALON 1 SAC ROUGE SPORT AVEC 3 PAIRE DE CHAUSSURE 1 PAIRE DE CHAUSSURE PURNLE FOUTBAL…».

50 declaration lists with the personal objects the deportees had to leave behind precisely document their content, the address where they were stored, which address they were to be delivered to in Zaire by a Swiss authority and who the owner is. This list of things is neatly noted, which includes the entire property of the deported and was filled out and signed by those deported on the plane on the day of their deportation in the forms provided for this purpose. As the sociologist Niklas Luhmann put it, administrative intervention is justified not by specific content, but by procedures. He is not concerned with legitimation through procedures in the sense of procedural law, but rather with the "absorption of uncertainty through selective steps" to reduce complexity. The legitimacy of an institution or a procedure is based on the assumption of its acceptance (Luhmann, 1983). Formalized rules and documents, a meticulous account of all costs of the deportation and property of the deportee demonstrate not only bureaucratic precision, but even more their effort to legitimize the monstrosity of the “action”. As the objects did not make it on the plane, they receive a life of their own in the bureaucratic labyrinth.

A few days after the deportation, the Federal Office for Police in Bern sent the following information to the FDFA by telegram: “With regard to the belongings left behind in Switzerland by those who have been deported, the quite elaborate surveys of the Cantonal Police Ticino, together with representatives of the concerned public health authorities and the local police, are still in progress, it is expected that we will receive the inventory lists at the beginning of next week since according to the information from the Cantonal Police it is already certain that some of the items found have not been paid (unpaid invoices available), it cannot be expected that all effects will be forwarded to Zaire, but that some of them will have to be returned to the supplier. It is planned to send you the inventory lists on which the released items are marked as soon as possible, so that you can orientate those affected and ask them to explain what should happen to their belongings and that they are willing to pay for the import costs themselves.” Then the complete names and birth dates of the people deported from the canton of Ticino and Vaud who left their objects behind are neatly listed:

N 128725 alves cartos m. 01.08.65

N 124929 areado avea gregorio j. 10.06.58

N 126516 banho joao manuel a. 18.10.55

N 128723 basi k. 17.12.57

N 99099 benga-ngyendoto n. 23.04.59

N 123624 benga-ngyendolo-eluki b. 01.11.60 and child benga-ngyendolo t. 01.10.85

…

The bills sent to the “Bundesamt für Polizeiwesen, Sektion Flüchtlinge” (Federal Police Office, Refugee Section) to Bern meticulously detail the enormous costs of the whole “action”. Just as properly documented as the objects left behind, the files contain the bills and accounts of the deportation flight (including the “befores” and “afters” of the flight). The deportation costs the canton police 44,122.35 Swiss Francs, which primarily covers the team hours of the police officers involved. According to the German magazine "Spiegel", the aircraft for the operation (tpye DC-10 from the Balair) costs the Swiss authorities an additional 320,000 Swiss Francs. Neither in the media, nor in the parliament or in public, the costs are addressed.

next...

«1 SAC SAMSONITE AVEC 8 PANTALON CUIR + 4 BLOUSON CUIR AVEC 1 VESTE BLANCHE AVEC 8 CENTURE AVEC 4 PANTALON TISSUT

1 VALISE AVEC 4 PAIRE DES CHAUSSURE 1 BLOUSON BLANCHE 1 BLOUSON NOIRE 5 PANTALON 1 SAC ROUGE SPORT AVEC 3 PAIRE DE CHAUSSURE 1 PAIRE DE CHAUSSURE PURNLE FOUTBAL…»

18 Sleep, to which we have a right. With all the calculations of the economy, colonial interests and political decision-making, aren't deportations also always attempts to finally capture what besets us, to finally master it, conquer it and to never have to fear again? Isn't this a reason for the approval, the consent to immunization, the insensibility that is required from us if we see deportation as a solution and just?

Have we ever stopped obeying orders? To obey. Looking away. Listening away. To be deceived against any better knowledge? Just in order not to listen to our fears and to believe that someone else might know better than us what is good and what is not? At dawn, when we sleep, we also take us away with the others who do not belong to us.

At dawn, when we sleep, we also take us away with the others who do not belong to us.

Abduct our sleep of the righteous to whom we believe we have a right. While the others who do not belong to us are picked up. From their rooms, cells, beds. Time has not stopped for houses to be surrounded at dawn. Unseen by anyone. Everything like in sleep. 140 police officers on duty. Officials, authorized persons. What are they thinking about? Of the children, the women, the sexual intercourse, the guns and bananas from Africa. The last “Tatort”, even then the three hundred and ninth episode.

next...

19 Immunization flights / What does not speak, that is us, who do not hear.

How to speak of an immunization to which we continually subject ourselves, to which we are continually subjected? Immune to us, to resistance, to sensation. Immune to everything that is there, that speaks, expresses itself and does not seem to count. Statistics, lists, names, everything organized, under control. This is how we settled into our fully automated democracies. Which we protect against those who do not belong in them. The words become inaudible. Belong to it or not like the people who belong to it or not. That is the order, that is the constant work of selection. This work, this smooth organization of processes, has not stopped since the ramp. It turns all processes into deportations. Also our language is deported. With the airplanes on their routes through time and space, negating any distance, the web of the sky is torn apart. Where the words we could give disappear. Words that we still refuse to give back to others. So our words have turned to stone, they always only say themselves. Seamless, merciless.

Where the words we could give disappear.

What screams in airplanes are children. And sometimes the musicians of a Russian orchestra sing to get something to drink. Like on one of my last long-haul flights from Osaka to Frankfurt. We flew with the day in artificial night. We were asked to close the windows. We had flown over Mongolia, the peaks of the Himalayas loomed in the distance, we were approaching the great rivers of Siberia, which look like a sea. The passengers dozed off in their seats like limp puppets. And while we lost all reference to space and time, we flew through an extinction, a callousness that staying in an airplane demands of us. At some point halfway through, I was standing in the back of the galley, trying to see something of the earth we were flying over through a narrow slit. When suddenly my eyes fell on the rows of seats that seemed to go on endlessly in front of me. Illuminated by the blue light of the monitors on which films were shown, in which they slaughtered, murdered, hunted, and avenged. Each in the light of his film, a sacred mission of war and vengeance. Under elimination off the earth.

next...

References

20

Blue Ethan, 2019, Means and Meanings of Carceral Mobility, in Chase Robert T. (ed.), Caging Borders and Carceral States, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press: 93-124.

David Thomas, Bouda Etemad and Schaufelbuehl Janick M. (eds.), 2005, Schwarze Geschäfte: Die Beteiligung von Schweizern an Sklaverei und Sklavenhandel im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert, Zürich: Limmat Verlag.

Drotbohm Heike, 2013, “Deportation: An Overview“, in Ness Immanuel (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration, Oxford, Blackwell: 1182-1188

Hartmann Peter, “Wie Mobutu die kleinen Schweizer das Zählen lehrte”, Die Weltwoche, 28 November 1985.

Gadient Irma, 2019, “Official Deportations of ‘Vagabonds’ and ‘Romanichas’ in Geneva and Haute-Savoie (1900-1914): Connecting Catagories of Exclusion“ in Lüthi Barbara and Skenderovic Damir (ed.), Changing Landscapes: Switzerland and Migration, Cham, Palgrave Macmillan: 101-122.

Inda Jonathan Xavier, 2011, “Borderzones of Enforcement: Criminalization, Workplace Raids, and Migrant Counterconducts“, in Squire, Vicky (ed.), The Contested Politics of Mobility: Borderzones and Irregularity, London, Routledge: 74–90.

Kretzen Friederike, 2018, “Versuch zu 68“, WIDERSPRUCH, Heft 71 (1): 139-149.

Kretzen Friederike, 2019, “Im Arbeitszimmer der Angst“, WIDERSPRUCH 73: 121-131.

Lüthi Barbara, 2020, Humans, Not Files: Deportation and Knowledge in Switzerland, GHI Bulletin Supplement 15: 165-179.

Lüthi Barbara and Skenderovic Damir, 2022, “Flucht, Asyl und die Logiken des Rassismus“, in dos Santos Pinto, Jovita et al. (eds.), Un/doing Race – Rassifizierung in der Schweiz, Zürich: Seismo.

Luhman Niklas, 1983, Legitimation durch Verfahren, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Matter Sonja, 2014, “Armut und Migration – Klasse und Nation: Die Fürsorge für ‘bedürftige Fremde’ an der Wende vom 19. zum 20. Jahrhundert in der Schweiz“, Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 54: 109-123.

Mountz Alison et al., 2012, Conceptualizing Detention: Mobility, Containment, Bordering, and Exclusion, Progress in Human Geography 37: 522-541.

Perrenoud Marc, 2018, “Congo (République democratique)”, Dictionnaire Historique de la Suisse (DHS), [Online], uploaded January 11,2018; accessed November 28 2021. URL: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/fr/articles/003474/2018-01-11/.

Purtschert Patricia, Falk Francesca and Lüthi Barbara, 2015, “Switzerland and Colonialism without Colonies: Reflections on the Status of Colonial Outsiders Interventions“, International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 18 (2): 286-302.

Purtschert Patricia, Lüthi Barbara and Falk Francesca (eds.), 2013, Postkoloniale Schweiz: Formen und Folgens eines Kolonialismus ohne Kolonien, 2. ed., Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

Skenderovic Damir and D’Amato Gianni, 2008, Mit dem Fremden politisieren: Rechtspopulismus und Migrationspolitik in der Schweiz seit den 1960er Jahren. Zürich: Chronos.

Spena Alessandro, 2016, “Resisting Immigration Detention“, European Journal of Migration and Law 18: 201-221.

Walters William, 2018, “Expulsion, Power, Mobilization“, Radical Philosophy 2 (3): 33-37.

Walters William, 2018, Aviation as Deportation Infrastructure: Airport, Planes, and Expulsion, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (16): 2796-2817.

Winter Yves, 2012, “Violence and Visibility“, New Political Science 34 (2): 195-202.

next... < br/>

Notes

21

1 The ancient fairy tale of the seven goats, collected by the Grimm brothers, deals in an almost paradigmatic way with the uncertainty that constitutes every house. Its interior cannot be sustained without an exit. And how can that which comes from outside be recognized with the means of the inner view?

In this fairy tale the mother sets out to search for food. She admonishes her seven little goats not to let anyone into the house except herself. She explicitly warns them about the wolf. Especially because the wolf can camouflage, transform, mask itself. They should always remember that his voice is deep and his paws are dark. As soon as she is gone, the wolf arrives. The little goats see black paws, hear his deep voice and won't let him in. Now the wolf goes to the baker, then to the miller, he first has dough spread on his paws, then flour. To raise his voice, he eats chalk. Again he stands in front of the goat door, shows his white paw, lets his high-pitched voice sound and the goats assume that this is their mother. They open the door for him and he eats them all except the seventh one, which is hidden in the clock cabinet. When the mother comes back, she finds the doors and windows torn open, the wolf lies behind the house and sleeps. Then she hears the voice of the goat hidden in the clock cabinet and together they cut open the wolf's belly, the goats come out alive and instead of the goats they fill the belly with stones. At the end of the fairy tale, the wolf wakes up, is thirsty, goes to the well - into which it will fall - and says the very sad sentence: I thought they were goats, but they are only stones.

Does that mean: as long as there are human beings, neither humans nor animals can be sure of what's in them? And how is it possible that it got there?

2 BA 15. Oktober, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

3 On the historical relations between Switzerland and Zaire see (Perrenoud, 2018).

4 BA, 22. November 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

5 BA, 11. November 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

6 BA, 3. November 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

7 BA, 30. September 1985: E4280A#1998/296#88*.

8 BA, 11. November 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

9 BA, 17. Januar 1987: E4280A#1998/296#89*.

10 Above all, this WE means a WE that names both subordinate and submissive together - or more simply - regards perpetrators and victims as an inseparable community. A we that is so often not talked about, that is interpreted as a denial of guilt and pain. Yet it is set here as WE, to speak of entanglements and connections between victims and perpetrators. It's about the possibility to become aware that what I am doing to the other I am also doing to myself. We cannot escape this context.

That is why the West is so brutal, crazy, empty, insane. That is why it isolates itself more and more against others, against itself, against life.

The guilt of the West is increasing, its aggressive isolation from the outside is directed above all against this guilt that it carries within itself and against which it tries to further protect itself.

What I have in mind here is the idea of a WE in which the most diverse WE’S can gather and differ.

11 “Internal Passenger Regulations“ der Swissair, BA, 13. Dezember 1984: E4300C- 01#1998/299#557*.

12 BA, 22. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

13 BA, 15. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

14 BA, 15. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

15 https://www.rts.ch/info/regions/jura/9239867-il-y-a-30-ans-lexpulsion-dune-famille-zairoise-secouait-le-jura-et-la-suisse.html ; https://www.luzernerzeitung.ch/international/der-beruhmteste-fluchtling-der-schweiz-ist-tot-ld.2129825?reduced=true.

16 BA, 15. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

17 During that time the migrants arriving in Switzerland mainly came from Zaire, Angola, Somalia, Eritrea/Ethiopia and in larger numbers from Sri Lanka and Turkey.

18 On the racialization of refugees during the 1980s and 1990s see Lüthi and Skenderovic, forthcoming 2022).

19 BA, 4. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

20 BA, 4. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

21 BA, 4. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

22 BA, 3. November 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

23 BA, 12. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

24 12. November, 1985: E4280A#1998/296#338*.

25 Tatort is a popular German detective film series that has been running continuously since 1970 with some 30 feature-length episodes per year.

Return to the beginning of the article...

-

https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/antiatlas-journal-05-buettiker-kretzen-luethi-action-black-autumn-the-genesis-of-air-deportation-in-switzerland-1985.pdf