antiAtlas #5 - 2022

Deportation monitoring in Germany and Nigeria: Asymmetric strategies, solidarity and activist knowledge production

Aino Korvensyrjä and Rex Osa

Abstract: The article explores deportation monitoring as a practice of migrant solidarity, mapping diverse sites in the German and Euro-African deportation regime. Drawing on our experience in anti-deportation organising and our research we reflect on the challenges for activist observation and documentation of deportation in Germany after 2015 and in post-deportation situations in Nigeria.

Aino Korvensyrjä is a social scientist and no border activist. Her doctoral thesis (University of Helsinki) analyses German deportation practices through the lens of migrant struggles.

Rex Osa is a migrant activist with refugee background. Active since 15 years in refugee struggles in Germany, in the recent years he has focused on West African activist networking and organising with deported persons in Nigeria.

Keywords: deportation, border regime, activism, monitoring, solidarity, Germany, West Africa

Acknowledgements We wish to acknowledge all collectives and individuals struggling against deportation, from whom we learned and who empowered us, in Germany, West Africa and elsewhere. In particular, we remember the struggles and knowledge of those who were deported or forced to leave. For improving the text, we thank the editors, Leonie Jegen, Minna Seikkula and Katharina Schoenes.

antiAtlas Journal #5 "Air Deportation"

Directed by ;William Walters, Clara Lecadet and Cédric Parizot

Design: Thierry Fournier

Editorial office: Maxime Maréchal

antiAtlas Journal

Director of the Publication: Jean Cristofol

Editorial Director: Cédric Parizot

Artistic direction: Thierry Fournier

Editorial Committee: Jean Cristofol, Thierry Fournier, Anna Guilló, Cédric Parizot, Manoël Penicaud

Gambians protesting in Stuttgart against planned deportations, December 2017. Photo: Rex Osa / Gambian community.

To quote this article: Aino Korvensyrjä and Rex Osa, "Deportation monitoring in Germany and Nigeria: Asymmetric strategies, solidarity and activist knowledge production", published on June 1st 2022, antiAtlas #5 | 2022, online, URL: www.antiatlas-journal.net/05-Korvensyrja-Osa-deportation-monitoring-in-germany-and-nigeria-asymmetric-strategies-solidarity-and-activist-knowledge-production

I. Situating monitoring in migrant solidarity

1 Deportation regimes expanded since 2015 in many parts of the world, and European states increasingly relied on coercion to physically and legally remove persons. Deportation practices extended over multiple locations, often hard to access. In this text we draw on our activist experience and research to reflect on strategies to counter deportation in its many forms and locations, and on the dynamics between state, activist and migrant practices and strategies.

Focusing on the seemingly simple, but actually challenging act of producing public information on deportation, we explore and appropriate the idea of monitoring. Historically, monitoring is closely linked to the expansion of modern-colonial states and their arsenal of observation technologies to govern people and things (Foucault, 1995; Browne, 2015). Today it is essential to diverse forms of border control (Casas-Cortes et al., 2015: 11–12). In the current migration-human rights nexus, monitoring is also used to observe and report on particular state practices to guarantee their public legitimacy and authority. Activist groups have however repurposed monitoring to reveal and challenge state-sanctioned violence in the border and deportation regime (Casas-Cortes et al., 2015: 11–12). This is not always easy, because deportation is in contemporary liberal states often characterised by secrecy (Oulios, 2016).

We expand here on this activist redefinition of monitoring, to reflect on what producing critical, public information on deportation entailed after 2015 in Germany and beyond. We propose that for monitoring to function as an intervention against exclusion and state violence, it needs not only to make deportation practices public but also to contribute to empowering people targeted by them.

Monitoring needs not only to make deportation practices public, but also to contribute to empowering people targeted by them

This draws on approaches developed in self-organised, migrant-led and no border groups. While borders and immigration law govern migrants as marginal subjects to the nation and the state, these approaches centre people on the move as full members of society and as political actors. Solidarity, essential to activist knowledge production, entails both a questioning of nation-state-centred ideas of belonging and entitlement, and efforts to enable the agency and self-organisation of migrant communities. The aim is to build autonomy from borders and the nation-state, in terms of consciousness, analysis and action (Cissé, 1999; Anderson et al., 2009; Osa, 2011a). We also emphasise the need to learn from the historical experience of migrant and no border struggles. In the following, we map different sites and practices of the deportation regime from this standpoint.

next...

2 Our collaboration as the working group Culture of Deportation began in 2015. We first documented the cases of two men who were deported from Germany to Nigeria, involving highly contested forms of Euro-African deportation cooperation. We later launched a blog to publish these (Culture of Deportation, 2017b, 2017a) and other documentations, to make accessible knowledge and analyses situated in migrant struggles against deportation, and reports on state practices and protests. Working with different groups and networks, we continued to document and support migrant struggles, as the German deportation campaigns unfolded in the years thereafter.

The term “culture of deportation” was coined in migrant-led activism in Germany. It highlights the everyday migrant experiences and historical continuities of deportation as a social practice that involves the ongoing production of hierarchies of human worth coupled with violence – racism (Jassey et al., 2019). Adopting this name in 2015, we sought to critically comment on the “welcome culture” (Willkommenskultur), in a moment when this popular mobilisation to “help refugees” peaked in Germany. During and after the 2015 “summer of migration” (Hess et al., 2017), control-centred and segregationist categories, attitudes and institutions were often reinforced and legitimised in volunteering and in public and corporate discourse alike (Omwenyeke, 2016, 2017; Altenried et al., 2018; Fleischmann, 2019).

The term “culture of deportation” was coined in migrant-led activism in Germany. It highlights the everyday migrant experiences and historical continuities of deportation

We came to our collaboration from different backgrounds: Rex Osa began organising starting from his own experience in the German asylum system, facing deportation soon after he arrived from Nigeria as a refugee. For over a decade he was active in The VOICE Refugee Forum, a migrant-led group challenging structural racism in the German asylum-deportation regime, and in the mixed network Caravan for the Rights of Refugees and Migrants. Aino Korvensyrjä was involved in a no border and migrant solidarity group in Finland, Free Movement Network. In 2016 she began her doctoral research on German deportation practices and West African migrants’ struggles against deportation.

The next section (II) presents the general context of our collaboration in Germany since 2015. We then move to map diverse sites and contested practices in the deportation regime, which we monitored with and alongside other groups and migrant collectives (sections III -VI). We also include brief historical reflections on practices before 2015. The discussion of these points will allow us to reflect on monitoring as a tool of activist knowledge production, challenging exclusive social solidarity limited by borders (section VII).

next...

II. German Culture of Deportation after 2015

3 The German context since 2015 was marked by three tendencies, all focused on the asylum system: the humanitarian “welcome culture”, a corporate “welcome culture” and a reinforced deportation agenda. In 2015, the humanitarian, popular enthusiasm for “helping refugees” was the most visible. This “welcome culture” imagined Germany as a safe haven for people fleeing wars, imagining people living in Germany as helpers of members of darker nations. The corporate “welcome culture” also evoked the national, as economy, as employers and economists petitioned the state and federal governments to tap into asylum migrants to tackle labour shortages in low-wage sectors (Altenried et al., 2018). These calls found resonance in Angela Merkel’s government. Alongside the European Commission, the government however also prepared a deportation offensive against failed asylum seekers. From 2016 onwards deportation campaigns were put in the public spotlight as a “national effort” (taz, 2016).

The humanitarian “welcome culture”, a corporate “welcome culture” and a reinforced deportation agenda

The year 2015 then signalled both a more open asylum policy than before, and an increase in deportation and related practices. Large numbers of people, particularly Syrian migrants, were granted protection in 2015-2016. Previously (West) Germany had regulated most asylum migration with rejection and temporary suspension of deportation, the so-called Duldung (Poutrus, 2019). In contrast to earlier decades’ general work bans, the government now facilitated the labour market entry of asylum seekers already during the procedure, and under restrictions, also after rejection (Altenried et al., 2018).

The “perspective to stay” (Bleibeperspektive) – a statistical protection rate of a given nationality – became a key administrative and legitimation tool for the deportation campaign. In 2015 the countries with a “good perspective to stay” were Syria, Eritrea, Iraq, Iran and Somalia. In 2019 only the two first ones remained on the list. The rest, citizens of countries without a good “perspective to stay”, often saw their social rights and labour market access restricted during the whole, often long, asylum procedure, and after it. At the bottom of this hierarchy of nationalities were “safe countries of origin”, including two West African and six Western Balkan countries. Migrants from these countries were in practice defined as categorically deportable.

next...

4 In 2015 the asylum system thus continued as a key infrastructure for deportation and managing “unwanted” migration (cf. Pieper, 2008 ; Ellermann, 2009). Between 2015 and 2019 Germany deported nearly 114 000 persons. In 2015-2016 about 50% of the deportations were carried out with chartered flights to countries of origin, mostly to the Western Balkans – defined as “safe countries of origin”. From 2017 onwards, Dublin deportations to states of the European Union were increased to 30-40% of the total. These were usually conducted on regular passenger flights. A significant drop in deportations occurred only in 2020, due to the restrictions related to the global COVID-19 pandemic. In 2021 the deportation campaign was revamped. Discouraged by harsh policies, between 2015 and 2019, 148 000 migrants used the federal program REAG / GARP, misleadingly called “voluntary return”, to deport themselves without escorts. Many more people left with other return programs run by German states (Länder), or without assistance altogether.

In 2015 the asylum system continued as a key infrastructure for deportation and managing “unwanted” migration

The large “first reception facilities” (Erstaufnahmeeinrichtungen) were expanded to serve in the logistics of sorting new arrivals and deporting the “unwanted”. Besides serving for accommodation and deportation enforcement, such semi-open asylum camps use social isolation, intense surveillance and economic destitution to encourage migrants to leave Germany “voluntarily”.

Deportations became increasingly normalised in the German public debate, often in reference to narratives of migrant criminality. Also, the availability of more humanitarian deportation options – “voluntary return” and “reintegration” aid after deportation or departure –, was used by state actors to justify regular deportations.

In the following, we explore key elements of the German deportation strategy: identification, charter and Dublin deportations and semi-open asylum facilities. Further, we analyse externalised border control, with a focus on Euro-African deportation cooperation and “reintegration” of deported migrants in West Africa. These increasingly securitised, concealed, outsourced and even militarised enforcement strategies responded to previous activist and migrant practices. They also aimed to discipline the unruly potentials of the “welcome culture” and publicly legitimise deportations. Activist groups, volunteers, NGOs, migrants and transnational networks modified their tactics and strategies, and continued to draw on older ones, to monitor and contest deportation practices across these sites.

next...

III. Monitoring identification and embassies

5 The first cases we documented – the two men deported to Nigeria in 2013 – were connected with migrant organising against identification practices and Euro-African deportation cooperation. Since two decades (Boekbinder, (n. d.)), African diaspora communities in Germany have put a spotlight on embassies as crucial nodes in the “deportation chain”. This section presents practices of observing and contesting African embassies’ and governments’ role in facilitating deportation from Germany.

African diaspora communities in Germany have put a spotlight on embassies as crucial nodes in the “deportation chain”

In Germany, deportation enforcement is often hindered by the lack of identity and travel documents. To tackle this, the immigration authorities (Ausländerbehörde) organise so-called embassy hearings to identify migrants. These are mostly held on the premises of German immigration authorities. Besides the immigration authorities and the federal police, officials from national embassies or external delegations are present, tasked with identifying the migrants. Later, if the identification has been positive – criteria and methods have not been made public by German authorities – an emergency travel certificate may be issued by the respective embassy for deportation. The migrants, obliged to attend, are mostly nationals of African and Asian countries – designated by German authorities with the racially coded term “problem states”. With these states Germany does not have readmission agreements to facilitate deportations without identity documents. In contrast, such agreements with the Western Balkan countries enabled large-scale deportations after 2015.

Migrants forced to these hearings are usually under temporarily suspended deportation (Duldung). The Duldung is an administrative instrument to deal with migrants whose deportation order cannot be enforced, either for the lack of travel documents, or any other reason. Administrators and right-wing politicians label those without documents as “identity refusers” and therefore as criminals. For many African and Asian nationals, whose mobility has been categorically restricted by Germany and other European countries, asylum applications lodged under second identities and travel without a passport are however crucial to access mobility. “Identity refusing” offers precarious protection against an otherwise certain deportation..

next...

1 Contesting identification, post-deportation solidarity

6 Before 2015, Osa was an organiser of the intense protests against the Nigerian embassy’s cooperation with the German authorities. These culminated in 2012, a year of widespread migrant-led protest against the German asylum-deportation regime (Odugbesan and Schwiertz, 2018). In May 2012, action days at the Nigerian embassy in Berlin denounced its role in deportation cooperation with German authorities, and its willingness to operate as a “clearing house for deportation of Black African Refugees” (The VOICE Refugee Forum, 2014). In a June 2012 protest, Osa handed a warning to the ambassador on behalf of the protestors, demanding that the embassy stop the identification practices. In October 2012, after the embassy had not responded to these concerns, the Nigerian community together with other activists occupied the embassy.

The protesters challenged deportation as a “colonial injustice” that reinforces and recreates the global colour line in the postcolonial order of nation-states

The protesters sought to deconstruct the immigration authorities’ rhetoric of “law enforcement”. They denounced the embassy hearings as violent and humiliating procedures targeting black and brown people, including strip searches, transportation in handcuffs, rude interrogation and other intimidation attempts. Osa had experienced these practices himself in a hearing in 2007. Further, participants to the hearings reported that physiognomy, accent and cultural markers, like traditional scars were used to assess national identity. Such was reminiscent of racial categorisation of colonised populations, fixing them on to territories and to a Eurocentric hierarchy of cultures and peoples (Osa, 2011b). On a more fundamental level, the protesters challenged deportation as a “colonial injustice” that reinforces and recreates the global colour line in the postcolonial order of nation-states (Osa, 2011b; Sharma, 2020).

next...

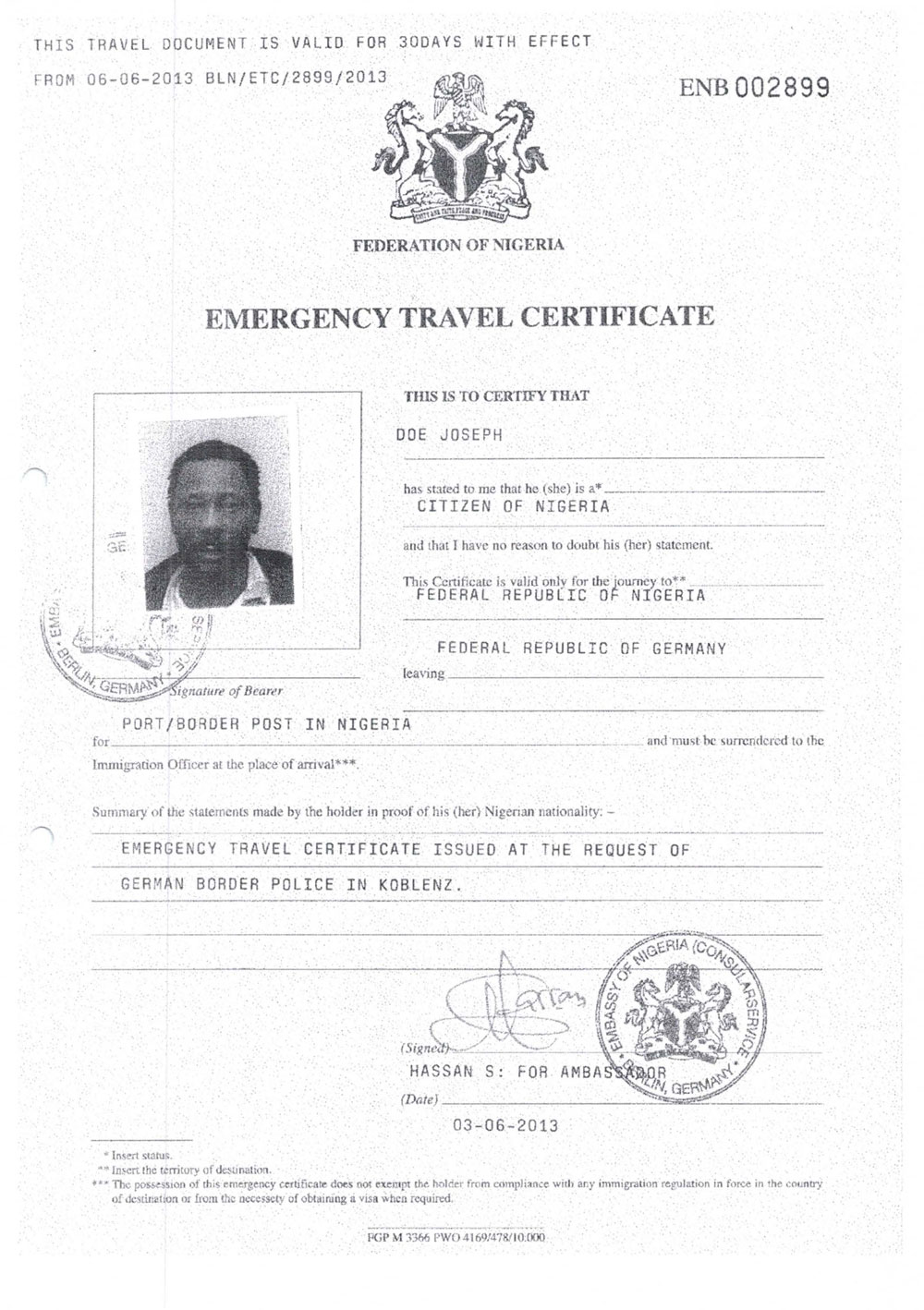

7 During these protests, Osa found out about the cases of Yusupha Jarboh and Joseph Koroma. Jarboh, a Gambian citizen was deported in June 2013 on a Frontex coordinated chartered flight from Germany to Nigeria. At the request of German immigration authorities, the officials of the Nigerian Embassy in Berlin had identified him as the Nigerian citizen Joseph Doe in an embassy hearing. Years earlier, he had sought asylum as the Liberian citizen Joseph Doe, to avoid deportation. Nigerian phone numbers found on his mobile telephone by the Federal Police served as “evidence” of his presumed Nigerian identity (Culture of Deportation, 2017b). Joseph Koroma, of Sierra Leonean citizenship, fell victim to the same identification practice and was deported with another charter flight to Lagos in the same year. His identification was based on a pseudo-scientific language test and assessment of physiognomy (Culture of Deportation, 2017a).

next...

Photo: Travel certificate for “Joseph Doe” alias Yusupha Jarboh

Video: Interviews with Yusupha Jarboh and Joseph Koroma, Kin Chui & Rex Osa (edit Claudio Feliziani), Culture of Deportation, Banjul Gambia and Freetown Sierra Leone. 2014 / 2016 - https://vimeo.com/179603466

Photos: Meeting with ex-migrants in The Gambia, Kin Chui, 2014.

8 In 2014 Osa travelled to Banjul and Freetown to meet with the two men and others deported from Europe. With the activist filmmaker Kin Chui he produced video recordings of these conversations. Since 2015 we completed this documentation together, with Claudio Feliziani, another activist and filmmaker, who had already participated in the 2012 protests against the Nigerian embassy.

In most cases activism stops at the moment of deportation

Drawing on the analyses developed in the protests against the embassy hearings, we aimed firstly, to raise public awareness of this practice. We documented the two cases not as exceptional misidentifications or individual human rights violations, but to highlight the struggle against the unequal, racialised access to mobility enforced in the deportation-border regime, performed in the embassy hearings and embodied in the two men’s migration experience. While German volunteers and humanitarian organisations often aim to protect migrants by assuring their incapability to produce the required identity documents, and thus their innocence, we wanted to focus on how the truth about identity was made and contested. Secondly, we wished to remember these two men after their deportation and to continue working in solidarity with them. In most cases activism stops at the moment of deportation. Thirdly, we wanted to centre and amplify migrant knowledge and analyses by documenting the struggles of people under pending deportation in the German asylum system. We focused particularly on the situation of suspended deportation (Duldung), in which also Jarboh and Koroma had spent many years after the rejection of their asylum request, before their deportation. For them, as for many others, the Duldung meant a work ban, movement restricted within the municipality (Residenzpflicht) and intense policing and criminalisation.

next...

Photos: Occupation of the Nigerian embassy in Berlin in October 2012, Rex Osa

Video: Protest at the Nigerian embassy in Berlin in June 2012. © David Rych 2012

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X7wZbz_1kjY

Video: Deportation identification hearing at the Dortmund Foreigners’ Authority in March 2016 - © Claudio Feliziani / Culture of Deportation - https://vimeo.com/181366851

2 Observing and challenging Euro-African deportation cooperation after 2015

9 After 2015 more West Africans sought asylum in Germany. They soon formed a significant group among migrants threatened by deportation. West Africa was set as a priority region for Euro-African deportation cooperation and border externalisation (Korvensyrjä, 2017). Embassy hearings continued to play an important role in the German deportation strategy to West Africa. At the same time, migrant communities often succeeded in nearly halting or significantly reducing deportation enforcements.

Migrant communities often succeeded in nearly halting or significantly reducing deportation enforcements

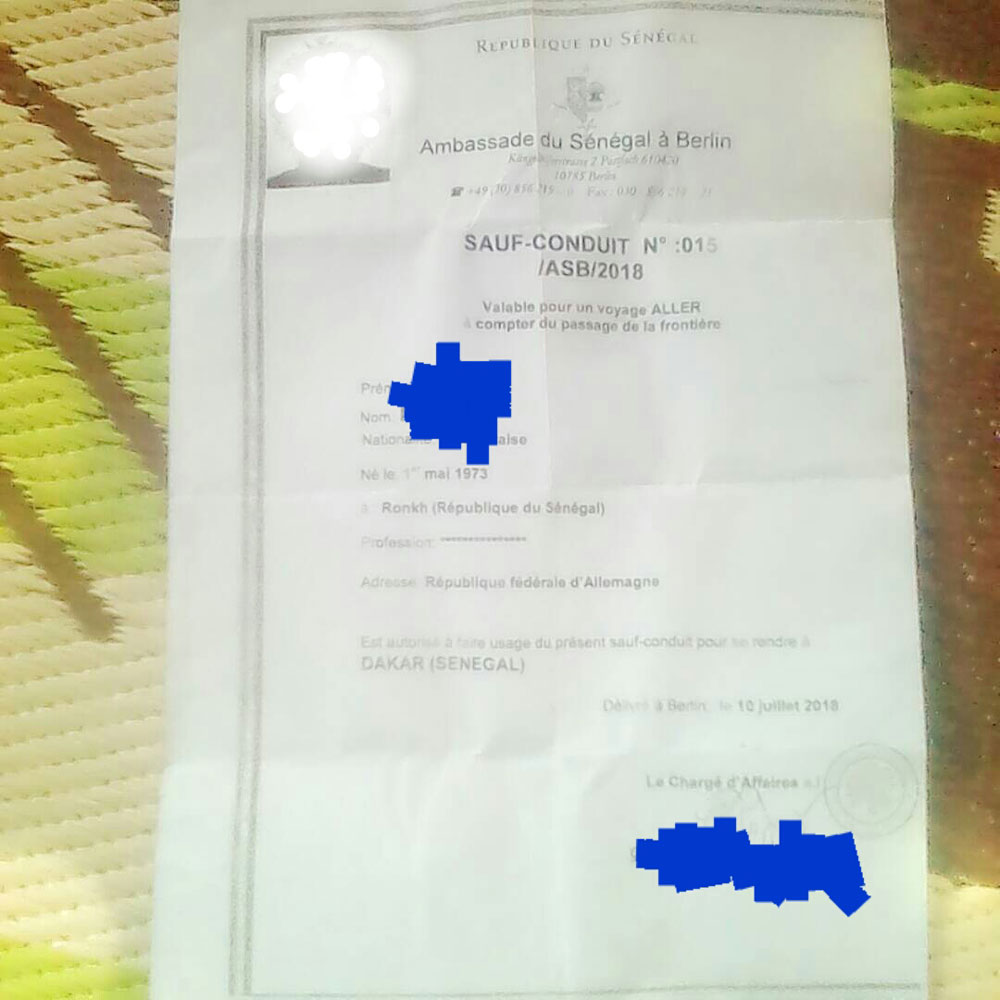

The Senegalese and Malian diaspora keenly monitored the actions of their embassies in Berlin after 2015 as the number of Senegalese and Malians under deportation increased. They repeatedly sent delegations to negotiate with the embassies, and organised protest actions, after learning of individual deportations carried out with travel certificates issued by the embassies. Their actions also responded to rumours and media information on planned large-scale deportations and readmission agreements. As in the Nigerian case earlier, they demanded the embassies to stop signing travel certificates, and their governments to halt negotiations for readmission agreements and the organisation of identification hearings. Further, they often alerted their communities of upcoming hearings.

next...

Travel certificate for a Senegalese national deported from Germany in 2018

10 In many West African countries deportation continued to be a sensitive issue after 2015. This was due to the role of migration in social life and the importance of remittances as a share of the GDP. Activists knew how to exploit this fact. Particularly effective was transnational organising joining migrant communities with activists in African countries and elsewhere in the European diaspora.

For instance, Senegalese activists, journalists and bloggers in the diaspora and in Senegal published on the concerns and protests of the migrant community in Germany under deportation. We contributed with a short report written by Korvensyrjä on a rare charter deportation from Germany to Senegal in July 2019, whose date was leaked in advance by members of the diaspora (Culture of Deportation, 2019).

Senegalese activists, journalists and bloggers in the diaspora and in Senegal published on the concerns and protests of the migrant community in Germany

The report drew on diaspora activists’ and German volunteers’ information and follow-up calls with the deported. Not stopping with denouncing the measure as “brutal”, “disrespectful and disruptive”, the report provided information on the administrative procedures through which the deported individuals ended up on the flight – despite having partners, children and jobs in Germany, or being seriously ill. Questioning the state narrative of deportation as “law enforcement”, the report explained that the Senegalese, like many other non-EU citizens, had little other options than to seek for asylum to stay in Germany, yet were destined to be rejected. Drawing on the deported person’s experiences, the report further showed how their later attempts to secure residence as partners or parents of persons with German residence, or as trainees and workers, had been combatted by immigration authorities. Immigration authorities did not hesitate to deceive the migrants or to breach the constitutional protection of the family to improve deportation figures (Culture of Deportation, 2019). For this flight, and for many others, persons unaware of the correct procedural order of applying for a residence permit were arrested – often having made the mistake of submitting their passport too early in the process. The report also highlighted the role of the Senegalese embassy in Berlin, in issuing travel certificates (sauf-conduits or laissez-passers) for persons without a passport, and the abandonment of the deported persons at arrival, “dumped at the new Dakar airport as if they were cargo” (Culture of Deportation, 2019). Thus questioning the stigma of criminality and illegality, widely associated both in Germany and in West Africa with deported persons, the report also provided information for activists, migrants and interested persons on how to prevent future deportations. It was broadly circulated in anti-deportation campaigning both in Senegal and Germany.

next...

11 Despite the German government’s plans to deport thousands of Senegalese, the yearly number of deportations from Germany to Senegal remained on a low two-digit level after 2015. Similarly, the protests of the Malian community in Germany were able to stop large-scale deportations. Groups in Mali, including the Malian Association of Deported People AME (Association Malienne des Expulsés) and Afrique-Europe-Interact convened protests in Bamako. In Berlin, several protests were organised at the Malian embassy. Malians also protested in France (Lecadet, 2017). The deportation of two Malians, Amadou Ba and Mamadou Drame, from Germany in January 2017 in a chartered flight just for them remained the last deportation with travel certificates for a long time. During the deportation both were cuffed at the hands and feet (Afrique-Europe-Interact, 2017). This measure provoked a further demonstration at the embassy in January 2017. The Malian government responded by halting identifications and the issuing of travel certificates to Malians in Germany against their will.

next...

Video: Protest at the Malian embassy in Berlin in January 2017. © Claudio Feliziani / Culture of Deportation 2017 - https://vimeo.com/205744424

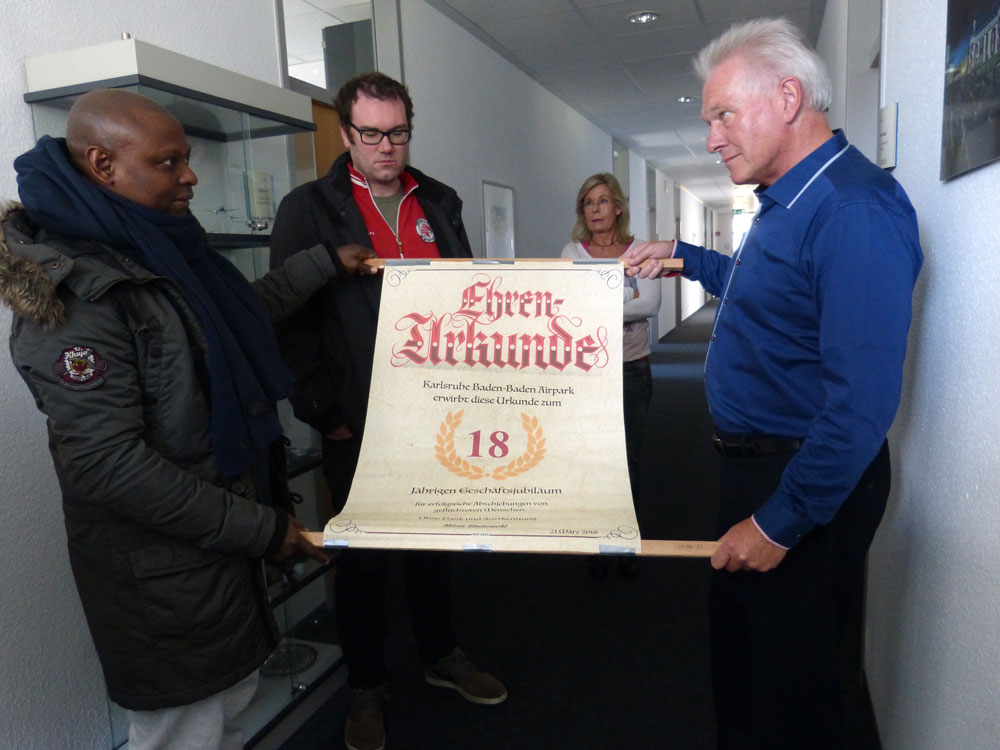

Demonstration of the Gambian community. Photos: Rex Osa.

12 The Gambian diaspora in Germany likewise mobilised against deportations since late 2017 and the readmission agreement concluded between the EU and The Gambia. Osa was in sustained exchange with the group, sharing from his experience in struggles against deportation cooperation. The Gambian community reached a significant success in early 2019: After a protest organised near Banjul, jointly by the diaspora group in Germany and activists and migrant family members in The Gambia, the Gambian government declared a moratorium on the monthly charter deportations from Germany. The moratorium lasted at least until the Gambian presidential elections in December 2021, with the exception of one charter flight in November 2020. This operation relied on extreme secrecy by the two governments and on the pretext that the deported were “criminal offenders”. We again challenged the way in which criminality was used as legitimation to resume the charter deportations, not only by the German government but also by German volunteers and the Gambian media (Korvensyrjä, 2020). After this flight, until the December 2021 elections, the Gambian government gave no further landing permits for charters.

In 2017 Germany also set a focus on Dublin deportations, deemed more feasible, as these did not require identity documents

In sum, in many cases these migrant and transnational actions significantly intervened in the feasibility of deportation enforcement. While somewhat more deportations were conducted to Nigeria, peaking with around 400 in 2019, this still fell below the German deportation target of 30 000 Nigerians (Deutsche Welle, 2018). This precarious success drew on migrant refusal to submit documents and on the importance of remittances and the diaspora to West African economies and electoral politics, strategically evoked by the protesters.

German authorities responded with harsh measures. Diverse policies were reinforced to make life intolerable for asylum migrants in camps and thus encourage “voluntary” deportation. In 2017 Germany also set a focus on Dublin deportations, deemed more feasible, as these did not require identity documents. West Africans were a highly targeted group, mostly deported to Italy. Together with the EU, Germany pressured African countries towards readmission agreements threatening with sanctions, and attracted them with diverse financial “packages” and “cooperation” offers. The EU also funded biometric databases in Senegal and Sierra Leone (Privacy International, 2020) with future potential to bypass the activist and community protection strategies. Further, European countries sought to contain migration from arriving to Europe. From late 2017 onwards West Africans were increasingly deported from “transit” countries on the African continent, such as Libya and Niger, via allegedly humanitarian “evacuations” and “voluntary returns” (Alpes, 2020). Also Morocco and Algeria conducted thousands of deportations of West Africans, monitored by Alarme Phone Sahara.

next...

IV. Chartered flights: Securing enforcement?

13 Most charters were organised to countries with which Germany had readmission agreements – particularly the Western Balkans – by-passing the requirement of travel documents. Besides logistical considerations, the German preference for chartered flights after 2015 followed a strategy to secure and conceal deportation enforcement. This responded to solidarity and migrant practices – monitoring, intervening, scandalising, evading and resisting. The strategy also hedged against the “welcome culture”, which besides its humanitarian paternalism and adherence to state-sanctioned categories (Omwenyeke, 2016, 2017) contained potentials of politicising and contesting public policies (Hinger, 2016).

Restricting the possibilities of migrant resistance, solidarity actions at the airport, on the plane and other factors that might interrupt enforcement

Since 2015, isolating asylum migrants to first reception facilities, from which deportations can be conducted without outsider interventions, sealed enforcement off from solidarity action. In 2015 an amendment also banned the announcement of deportation dates to migrants ahead of enforcement. With this, the Federal Ministry of the Interior countered activist and migrant strategies of blocking enforcement with sit-in or stand-in actions in camps, migrant absenteeism and last-minute legal action and solidarity campaigning.

Charter deportations extend such effects, by restricting the possibilities of migrant resistance, solidarity actions at the airport, on the plane and other factors that might interrupt enforcement (Ellermann, 2009; Walters, 2018). They are operated outside of normal flight schedules, often from smaller airports and with airlines specialising in charter services. Large numbers of police officers and other security personnel secure these flights, by far outnumbering the deportees. Rare cases of direct action have succeeded in addressing the practice. The Stansted 15 group did so in the in 2017, at the cost of a prolonged legal struggle against terrorism-related criminal charges (Institute of Race Relations, 2019: 22).

German authorities also used charters flights as strategy to increase public acceptability of deportations since 2015. Charters deportations hide violent state practices from view. Investment in chartered flights began after the debate and campaigning sparked by the death of Sudanese Aamir Ageeb. He was asphyxiated by the German police on a passenger flight to Cairo in 2001 (Ellermann, 2009).

After 2015 Germany also began to expand detention capacity, and new legislation facilitated short-term detention pending deportation, often ordered before charter deportations.

next...

Video: Lufthansa Deportation Class Campaign, Kino-Spot, 2001

14 Activists developed novel monitoring practices to work against the chartered deportations since 2015. Publicly announcing dates of charter deportations became a widespread activist strategy in Germany. By drawing on diverse sources, inventive groups such as the Aktion Bleiberecht in Freiburg were able to produce nearly complete flight calendars even several months ahead, to warn migrant and activist communities. Regional refugee councils and their umbrella organisation Pro Asyl also got involved, monitoring deportations to Afghanistan. The Deportation Alarm developed by No Border Assembly since 2020 is the most comprehensive calendar to date. Their method of flight tracking using free online software seems to also produce information on charter flights that is more accurate than German government sources.

next...

Photos: Aktion Bleiberecht.

Photo: Screenshot, website Deportation Alarm.

15 The Freiburg activists further monitored flights in person at the Karlsruhe Baden-Baden airport, used as a nation-wide hub for Balkan deportations. They and members of the Roma community travelled to the airport to meet the people who were escorted there by the police. They mostly observed at a distance required by the police, and wrote reports. The activists organised protest actions at the airport, including demonstrations and press conferences, often coinciding with the schedules of the chartered jets.

next...

16 Osa took such monitoring to a new location in August 2019, as he flew to Lagos, to monitor a charter deportation arriving from Frankfurt. With journalists and members of local migrant rights’ groups, he waited on 19th August at the gate of the cargo section of the Murtala Muhammed main airport in Lagos, to meet the people arriving from Germany. This is where people deported are released, after being processed by the Nigerian immigration and literally treated as cargo.

Later, Osa has repeated the observation and reception at the cargo gate each time a charter flight has arrived from Germany. A local team now assists the landings, when he cannot be there himself. He usually notifies Lagos-based journalists in advance of the landings. His own reports usually draw on information acquired before deportation in Germany, as he has accompanied the cases of people under deportation, and on conversations with the deported people after deportation.

next...

17 The monitoring in Nigeria aims to raise critical awareness of deportation on both ends, in Germany and in Nigeria. In Nigeria deportation has until now not been publicly politicised, unlike in many other West African countries. Besides providing emergency support for deported persons, Osa’s team maintains contact with the deported people and documents their stories. Osa often knows of their cases before deportation, having accompanied them in Germany in legal procedures. Drawing on these sources, his reports question the denial of violence and brutality associated with deportation and show the violence of (European) immigration law in practice. With the information drawn on the monitoring, Osa has also furnished parliamentary inquiries in Germany concerning charter deportations to Nigeria. In Germany, parliamentary inquiries, often posed by the Left party, drawing on concerns expressed by diverse groups, are crucial for obtaining information on deportations. The Federal Ministry of the Interior is otherwise reticent in sharing detailed data.

His reports question the denial of violence and brutality associated with deportation

In early 2019 the Federal Ministry of the Interior announced plans to criminalise the communication of deportation dates in advance by any individual. The plan was part of the draft for the Orderly Return Act, a broader package of harsher deportation policy. It resonated with European governments’ recent tendency to criminalise solidarity (Institute of Race Relations, 2019). The draft also included an ambiguously formulated plan to criminalise all counselling of migrants on how to avoid deportation enforcement. After public criticism from many sides, these plans did not enter the final version of the law passed in 2019. Only public officials were prohibited from leaking deportation dates. The deportation offensive however continued, and legitimising narratives of migrant criminality and humanitarian deportation were further reinforced.

next...

Photos: Rex Osa / DERS.

V. Camps and Dublin

Video: “We are refugees, not prisoners!” Demonstration of the residents of the Bamberg reception-deportation centre, Bavaria, in January 2018 - © Aino Korvensyrjä / Culture of Deportation - https://vimeo.com/252197618

Photos: Aino Korvensyrjä / Culture of Deportation.

18 From 2017 onwards, we were involved in documenting and supporting the struggles of inhabitants of the large first reception facilities. In southern Germany – Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg –, where our activism and research focused, the camp policies were particularly harsh. Yet across Germany the federal government aimed to deport asylum seekers without “perspective to stay” directly from the large facilities of first reception. We first briefly introduce preceding struggles.

next...

See series of photos below: Rex Osa, 2010.

1 Emergence of camps and anti-camp organising

Welcome to the Isolation lager standing behind the Trees on the Hill

The monitored entrance

Control Administration

Security check Point and Social Office/Lager Post collection point

(Privacy abuse Point)

Letter displayed behind the Glass

Another example of deprived Privacy in another Lager in Baden Wurttemberg

Available stock of milk and yogurt products

Milk options on 15.11.10

Sausage with neither manufacturing nor expiry dates / Butter to expire 2 days later

Bathrooms

Available rather than preferable food offer for two Refugee Victims

{What kind of meal can one make out of this?}

Yoghurt expired since 14.05.2009 – nevertheless, we must be grateful that Germany offers what our Home Country could not afford.

Most of the doors are seen to have been burgled and patched

Doctors visiting time, but not consistent

Available beds for refugees

Washing machines to serve far more than 100 Persons (one of them has defected)

Kitchen serving more than 30 Persons

19 Activists refer to (West) German asylum facilities with the term Lager (camp) or Isolationslager (isolation camp). These are an infrastructure for ensuring deportability in the widest sense dating back to late 1970s and early 1980s. Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg were significant in influencing the development of this model combining accommodation and deportation (Pieper, 2008). During the 1990s “asylum crisis”, migrant-led organising challenged it. The VOICE Refugee Forum was initiated in 1994 by West African migrants living in camps in the former East Germany. The network Caravan for the Rights of Refugees and Migrants emerged out of a nation-wide tour of camps later in the decade. Women in Exile was founded by refugee women in Brandenburg in 2002. Using inventive ways, these migrant and citizen organisers brought critical monitoring, empowerment and protest to the camps, often derelict buildings repurposed as asylum accommodations in remote, rural areas. During the 2010 Break Isolation campaign, in which Osa participated, activists of these networks travelled to the remote locations of the camps, to meet with the residents, discuss their problems and inspect the facilities together.

next...

20 The transregional bus tours aimed to empower solidarity among people living in the camps, who typically experienced intense fear of deportation, loss of autonomy and dependency produced by the numerous legal and administrative restrictions, part of the repressive humanitarian governance of their lives. The tours, documentation and reports produced in their course, also aimed to inform the broader communities of activists and local populations, thus also enabling solidarity by people outside of the camps.

Intense fear of deportation, loss of autonomy and dependency produced by the numerous legal and administrative restrictions

Organising against camps culminated in 2012-2014. In early 2012 there were several hunger strikes in Bavarian facilities. Their residents abandoned the camps and occupied spaces in town centres with tents. The Refugee Protest March from Bavaria to Berlin followed in the fall. From 2012 to 2014 protesters camped on a centrally located square in Berlin, the Oranienplatz in Kreuzberg, and occupied a nearby school, until both were emptied by thousands of police officers.

next...

Video: Liberation Bus Tour 2013 visits Witthoh, May 2013.

Photos: Ulrich Riebe

2 The camp as a contested space after 2015

21 When the “welcome culture” peaked in 2015, many activists who had run the previous protests were exhausted. The increasing securitisation of the first reception facilities after 2015 also made practices of solidarity and collective organising harder. Many new camps in Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg now had electronic access controls, visitor limitations, and even a complete visitor ban. Any resident staying away for more than three days would be erased from the camp register. Federal amendments introduced successive restrictions for the residents, including work bans, movement restrictions and a shift from cash to in-kind allowance. Bavaria set-up so-called ANKER centres, inspired by extra-large reception-deportation centres with capacity for up to some thousand persons, established in Bamberg and Ingolstadt-Manching in 2015. The ANKER model was embraced by the federal government in 2018. The model proposed to house asylum applicants in large facilities until their positive decision or deportation, gathering all relevant authorities under the same roof. The inhabitants’ contacts with the exterior world were to be minimised in order to maximise their deportability.

The increasing securitisation of the first reception facilities after 2015 also made practices of solidarity and collective organising harder

Together with other local groups, we accompanied protests in the camps, offering practical and political support to publish protesters’ concerns, to initiate legal and political action, and to facilitate transregional networking.

next...

Video: Demonstration of the residents of the Deggendorf first reception facility, Bavaria, in December 2017. © Aino Korvensyrjä / Culture of Deportation, 2017

https://vimeo.com/248613638

22< Many protests addressed the immediate camp conditions: regular nightly deportations, refusal of the right to work, study, receive cash, and move out of the camps, heavy-handed policing and violence by guards. In several Bavarian centres, people under pending deportation were not issued any documents at all besides a camp resident card. Leaving the camp, the police could treat them as “illegal” in the frequent controls based on racial profiling. These conditions, intense policing and frequent “transfers” of migrants to other camps, particularly after protests, contributed to the fragility of this organising.

Police raids of Bavarian asylum camps became a weekly routine in 2017

Police raids of Bavarian asylum camps became a weekly routine in 2017, after a police law amendment declared all Bavarian asylum accommodations as “dangerous places” (police jargon). This enabled conducting identity controls without reasonable suspicion (Ziyal, Yunus and Böhm, Johanna, 2020). Unchecked violence by security guards intimidated the residents and was commonly addressed in the protests. Both forms of policing reinforced the camp inhabitants’ sense of isolation, functioned to suppress potential and actual protests, and produced public ideas of “dangerous” and “undeserving” groups. Many left the camps and Germany.

next...

23 During the intense Dublin deportation campaign in 2017- 2019, frequent nightly deportation enforcements converted the facilities into sites of hide and seek. Changing beds within the centre or staying awake during the night when most enforcements took place were common tactics to evade deportation.

The media and politicians reproduced and amplified the police narrative of criminal asylum seekers and violent black men

In 2018 several more spectacular police raids targeted West African men in different camps in Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg. The police announced these Dublin deportation-related raids as responses to residents setting up “alarm systems” to warn others and “rioting” – that is, obstructing nightly deportation enforcement by spontaneous, collective solidarity. The raids were conducted by hundreds of riot police, performing identity and room controls, and multiple arrests. The media and politicians reproduced and amplified the police narrative of criminal asylum seekers and violent black men. These moral panics spurred new legislative and policy projects for a tougher deportation policy.

The first such raid, on March 14 2018, targeted the Gambian community in the Bavarian Donauwörth. The raid ended a longer protest of the Gambian community. For months, they had demanded access to health care, work, money and documents. A week before the raid, they had gone on strike for the second time, to back their demands, stopping all work within the camp, where they were performing essential maintenance work like cleaning and dishwashing for 80c per hour. The raid ended this strike: 30 Gambians were taken into custody, charged with “breaching the peace” during the enforcement of a Dublin deportation. After two months, the local court proclaimed all of them guilty.

next...

Photos: Rex Osa / Culture of Deportation.

Video: Interview with David Jassey on the police raid in Donauwörth. © Aino Korvensyrjä / Culture of Deportation, 2017 - https://vimeo.com/296197583

24 In Ellwangen, the state of Baden-Württemberg, over 500 officers raided a first reception facility on May 3, 2018. The action produced a nation-wide moral panic on “violent” Black men “stopping a deportation” to Italy three days before the raid (Jakob, 2018). A similar raid was conducted after a failed Dublin deportation attempt in the Bavarian Stephansposching in October 2018, a large facility housing people from West African countries.

next...

25 Overcoming their initial fear of repression, the residents of these camps publicly communicated their perspective, challenging the police and media reports and denouncing the raids as racist police violence. With other groups, we supported their organising and legal action, and monitored the later court proceedings in which the migrants were accused of resistance against the police or “breaching the peace”. This gave us information on police tactics, which often bent the law to achieve their desired goals. For instance, during the proceedings at the Ellwangen Local Court against inhabitants of the facility, arrested during the raid of May 3 2018, we learned that no search warrant had been issued by the court to raid the camp. Such is required for the police to enter homes and accommodations in Germany (Article 13, Basic Law). A former resident of the facility, Alassa M. now could take legal action against the raid. However, state agencies elaborated further legal arguments and proposals to secure police powers in the camps.

The raids were also a response to migrant practices of counter-surveillance

The criminalising narrative on the raids facilitated the passing of the 2019 Orderly Return Act and harsher deportation and camp policies. Yet migrant protests and independent reports based on their accounts, showing the camps as spaces structured by the violence of deportation, were able to elicit nation-wide activist solidarity.

As we noted, the raids were also a response to migrant practices of counter-surveillance. They sought to undermine migrants’ tactics of protecting themselves and their communities from deportation, and in some cases, sought to directly suppress their protest organising, including strikes and stay-ins.

next...

Video: Press conference of the residents of the Ellwangen first reception facility, Baden-Württemberg, in May 2018 after a police raid of the camp. © Aino Korvensyrjä / Culture of Deportation, 2018 - https://vimeo.com/269728539

VI. Monitoring “reintegration” and post-deportation, creating autonomous spaces

26 The European border externalisation strategy after 2015 further outsourced migration controls to third countries, companies, international and para-state organisations. To shift contested migration control beyond European territory, and beyond public accountability was partly a response to migrant and activist struggles in Europe. It included efforts to externalise deportation policy, with West Africa as a priority target region.

To shift contested migration control beyond European territory, and beyond public accountability was partly a response to migrant and activist struggles in Europe

As the Malian activist Ousmane Diarra (AME, Malian Association of Deported People) predicted in a workshop in May 2016 in Vienna, the Valletta Action Plan agreed between European and African governments in November 2015 on Malta, would transform the (West) African migration control landscape. The plan coupled development aid with externalised migration control (Korvensyrjä, 2017). European funders now increasingly commissioned West African societies and NGOs to prevent young people from migrating, and to “reintegrate” people deported from Europe and from North African “transit countries” (Alpes, 2020), by offering modest financial aid, job market counselling and short trainings. Many European-funded organisations initiated or expanded such activities in West Africa. These politics, including the euphemisms “reintegration” and “return”, were part of the EU strategy to make deportation more palatable for African states, their citizens and for European publics.

Osa was concerned about this ongoing export to Africa of control policies he had fought against in Germany. Inspired by initiatives like the AME that politicised deportation and supported the self-organisation of deported people in French-speaking West Africa, he had begun to map possibilities to establish effective support in Nigeria for people after deportation. Decisive was his visit in 2014 to Yusupha Jarboh in The Gambia and Joseph Koroma in Sierra Leone after their deportation from Germany in 2013 as “Nigerians”. After several study and networking trips to West African countries since 2016, he initiated the project in 2018 in his natal Benin City, the Nigerian capital for outbound migration to different parts of the world. A key insight guiding The Migration Information Point (MIP) has been to work in solidarity with people after deportation – as we mentioned, rarely accomplished by activists in Europe. After 2015, due to the policies described above, this objective became more urgent.

The MIP aims to create a space in Benin City where people with migration experience can feel at home and exchange with each other. The broader objective is to build a platform for critical migration knowledge, based on empowering people with migration experience as experts and political actors, able to radically challenge the perspective of control. The centre also aims to develop exchanges with activists and researchers from other African countries and Europe, with a focus on West African activist networking. The MIP is closely connected to the regular monitoring of charter deportations from Germany to Lagos.

next...

Photos: Rex Osa / MIP.

27 An important challenge addressed by the project is to create critical public awareness in Nigeria on European migration policies, beyond the dominant European narratives. Such are imposed by European and international migration governance actors active in Nigeria and in Benin City, which became a new boomtown of the Euro-African migration industry (Andersson, 2014). The International Organisation for Migration (IOM), the German development agency (GIZ) and other European countries’ agencies aim at limiting and stopping migration. Adopting their discourse on “illegal” or “irregular” migration and the “fight against trafficking” is a precondition to get funded, both for local NGOs and individual migrants. Also African migration research is affected by this agenda. This ideological work is often offered to local populations as “information” on “safe migration” and the “risks of irregular migration”.

The rhetoric of “reintegration”, rising after the Valletta Summit and spread by programs such as the German Perspektive Heimat, seeks to neutralise activist criticisms of deportation as violence and postcolonial racism. Much like “return”, the term suggests a harmonious homecoming to one’s supposed place, as a recipient of European help. When the IOM or GIZ talk about “empowering returnees” to set up businesses, “awareness-raising” and strengthening “peer-to-peer exchange”, these terms appropriate grassroots initiatives’ discourse. The similarly sounding terms are however mobilised for a different objective: strengthening European migration governance in Africa. In recent years the IOM program Migrants as Messengers has furthermore engaged individual “returnees” as “messengers”, to spread European migration narratives as their “own stories” through social media and advocacy work. As compensation, they receive meagre travel fees and meals.

In this context, reintegration packages offering short professional trainings for “returnees” from Europe and North Africa and counselling to meet the miserable job markets take on multiple functions. They discursively legitimise European control policies, discipline the victims of migration control with participatory methods and aim to prevent them from leaving again.

The rhetoric of “reintegration” seeks to neutralise activist criticisms of deportation as violence and postcolonial racism

Since 2018 monitoring the “reintegration” branch of the expanding migration industry became central to Osa’s work in Benin City. Confronting German and European-funded organisations in Nigeria and the Nigerian government agencies on the neglect of deported persons and misleading rhetoric, has in his experience often resulted in these agencies adapting their ways of working and speaking. Instead of a perspective change, these adaptations have aimed to an improved, presumably more humane and acceptable governance of “return migration”. Many “returnees” with whom Osa works, participate at the same time in European-funded programs offering training or modest financial support, with all ideological strings attached.

The working context of more radical initiatives like the MIP thus remains wrought by contradictions and challenges as the boom of exporting German “help” and “information” to West Africa continues. The NGO sector continues to invent publicly funded projects and German volunteers establish humanitarian and development initiatives in these countries.

next...

VII. Monitoring as an intervention

28 Deportation is a complex, shifting field of struggles. We analysed some of the moves on the field after 2015. During this time, German state and the EU refined deportation strategies, responding to activist and migrant practices and criticisms, and disciplining the German “welcome culture”. The activist and migrant practices and strategies we presented used monitoring as a tool to challenge identification for deportation and embassy deportation cooperation, charter deportations, policing of semi-open camps and Dublin deportations, as well as the governance of post-deportation situations and “reintegration” in West Africa.

The problem is the way in which deportation, borders and immigration law frame noncitizens as targets of control

To conclude, we highlight our understanding of monitoring as an intervention in state practices. The monitoring by activists and migrants, reviewed in this article, did and does not simply aim at making deportation public in the abstract. Rather than “generate public attention while leaving the core of the problem untouched” (Osa, 2011a), it attempts to confront the problem. The problem is the way in which deportation, borders and immigration law frame noncitizens as targets of control, instead of full members of society or political subjects. Monitoring as activist knowledge production therefore also needs “to support the self-organisation of the oppressed” (Osa, 2011a).

This support is what we mean with empowerment. A notoriously precarious and asymmetric situation, empowerment nevertheless has the potential to open up a multidimensional process of knowledge production: We learn about the realities of living under borders and policing, as others share their experiences and analyses, and overcome the common fear of repression, shame or doubt of any possibility of change. Empowerment begins with facilitating basic information-sharing and critical exchange, either by members of a community or by external activists. The “knowledge situated in migration” (Güleç and Kowalska, 2018) emerging from such exchanges may be further engaged in structural critiques of law and borders by (migrant) activists and scholars. In this way systemic forms of racism, enacted by law and borders, can be denounced – instead of individual “human rights violations”. Such analyses can in turn strengthen solidarity and migrant action.

Such a perspective of building autonomy from borders and the nation-state (Cissé, 1999; Anderson et al., 2009 ; Osa, 2011a) sets our approach apart from monitoring conducted by state agencies, but also from journalist and humanitarian monitoring with reformist goals. It starkly contrasts with the use of the term empowerment in European “return” and “reintegration” programs, which through participatory rhetoric discipline and instrumentalise migrants to accept and promote European migration policies. Our understanding of migrant empowerment prefigures a society and world beyond borders, of which people who migrated are full members. We believe that working from this radical standpoint can shift the current control-centred logics – humanitarian, repressive and exploitative – and produce systemic change.

next...

References

29

Afrique-Europe-Interact, 2017, Folter: Gefesselt als Paket nach Mali. (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://afrique-europe-interact.net/1605-0-Gefesselt-als-Paket-nach-Mali.html

Akkerman Mark, 2018, "Expanding the fortress. The policies, the profiteers and the people shaped by EU’s border externalisation programme", Amsterdam, Transnational Institute. (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://www.tni.org/files/publication-downloads/expanding_the_fortress_-_1.6_may_11.pdf

Alpes JIll, 2020, "Emergency returns by IOM from Libya and Niger. A protection response or a source of protection concerns?", Berlin and Frankfurt am Main, Brot für die Welt, medico international e.v. (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://www.medico.de/fileadmin/user_upload/media/rueckkehr-studie-en.pdf

Altenried Moritz, Bojadžijev Manuela, Höfler Leif, Mezzadra Sandro and Wallis Mira, 2018, "Logistical Borderscapes", South Atlantic Quarterly, vol. 117, n° 2 : 291‑312.

Anderson Bridget, Sharma Nandita and Wright Cynthia, 2009, "Editorial: Why No Borders?", Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees, vol. 26, n° 2 : 5‑18.

Andersson Ruben, 2014, Illegality, Inc.: Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe, Oakland, California, University of California Press.

Boekbinder Gerit, (n. d.), "Identitätsfeststellungen und der Handel mit ’Heimreisepapieren’: Gemeinsam gegen das korrupte Geschäft", Afrique-Europe-Interact (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://afrique-europe-interact.net/239-0-artikel-ebs.html

Browne Simone, 2015, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, Durham, Duke University Press.

Casas-Cortes Maribel, Cobarrubias Sebastian, De Genova Nicholas, et al., 2015, "New Keywords: Migration and Borders", Cultural Studies, vol. 29, n° 1 : 55‑87.

Cissé Madjiguène, 1999, Parole de sans-papiers, Paris, La Dispute.

Culture of Deportation, 2017a, "FILE: Joseph Koroma in Germany 2006 – 2013", (Online). 1 June 2017. (accessed 19 January 2022). http://cultureofdeportation.org/2017/06/01/file-joseph-koroma-in-germany-2006-2013/

———, 2017b, "FILE: Yusupha Jarboh in Germany 1994-2013", (Online). 1 June 2017. (accessed 19 January 2022). http://cultureofdeportation.org/2017/06/01/file-yusupha-jarboh-in-germany-1994-2013/

———, 2019, "Charter Deportation Germany-Senegal 16.07.19: Report (EN) – Rapport (FR) – Bericht (D)",( Online). 19 July 2019. (accessed 19 January 2022). http://cultureofdeportation.org/2019/07/19/charter-160719-muc-senegal/

Culture of Deportation and Justizwatch, 2018, "Security guard violence in the AEO Bamberg – state-sanctioned criminalisation and persecution of refugees", Online). 8 May 2018. (accessed 19 January 2022)http://cultureofdeportation.org/2018/05/07/bamberg/

———, 2021, "VG Stuttgart legitimiert rassistische Polizeigewalt in Ellwangen: Prozessbericht 18.2.2021 / Trial Report 18th Feb 2021", (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). http://cultureofdeportation.org/2021/02/23/vg-stuttgart-ellwangen-bericht/

Dahlkamp Jürgen and Stark Holger, 2006, "Achse der Aussitzer", Spiegel (Online). 5 November 2006. (accessed 19 January 2022). https://www.spiegel.de/politik/achse-der-aussitzer-a-98a4888f-0002-0001-0000-000049450805

Deutsche Welle Deutsche, 2018, "Germany proposes plan to repatriate 30,000 Nigerians", (Online). 17 May 2018. (accessed 19 January 2022). https://www.dw.com/en/germany-proposes-plan-to-repatriate-30000-nigerians/a-43824080

Ellermann Antje, 2009, States Against Migrants: Deportation in Germany and the United States, Cambridge (England); New York, Cambridge University Press.

Fleischmann Larissa, 2019, "Making Volunteering with Refugees Governable: The Contested Role of ‘Civil Society’ in the German Welcome Culture", Social Inclusion, vol. 7, n° 2 : 64‑73.

Foucault Michel, 1995, Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison, London, Penguin Classics.

Güleç Ayse and Kowalska Patrycja, 2018, "Vom Rand ins Zentrum", analyse & kritik 635 (Online). 20 February 2018. (accessed 19 January 2022). https://archiv.akweb.de/ak_s/ak635/15.htm

Hess Sabine, Kasparek Bernd, Kron Stefanie, Rodatz Mathias, Schwertl Maria and Sontowski Simon, 2017, Der lange Sommer der Migration, Berlin, Assoziation A.

Hinger Sophie, 2016, "Asylum in Germany: The Making of the ‘Crisis’ and the Role of Civil Society", Human Geography, vol. 9, n° 2 : 78‑88.

Hinger Sophie and Kirchhoff Maren, 2019, "Andauerndes Ringen um Teilhabe: Dynamiken kollektiver Proteste gegen Abschiebung in Osnabrück (2014-2017)", Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, vol. 32, n° 3 : 350‑363.

Institute of Race Relations, 2019, "When witnesses won’t be silenced: citizens’ solidarity and criminalisation", London, Institute of Race Relations. (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://irr.org.uk/product/when-witnesses-wont-be-silenced-citizens-solidarity-and-criminalisation/

Jakob Christian, 2018, "Neuer Blick auf Vorfall in Unterkunft: Was geschah in Ellwangen?", taz (Online). 3 May 2018. (accessed 19 January 2022). https://taz.de/!5500584/

Jassey David, Korvensyrjä Aino, Naiumad Seda and Osa Rex, 2019, "Culture of Deportation. Surviving the German Asylum System. Seda Naiumad in Conversation with Aino Korvensyrjä, David Jassey and Rex Osa", in Ankersentrum (surviving in the ruinous ruin), ed. by Natascha Süder Happelmann and Franciska Zólyom, Berlin, Archive Books.

Korvensyrjä Aino, 2017, "The Valletta Process and the Westphalian Imaginary of Migration Research", movements. journal for critical migration and border regime studies, vol. 3, n° 1. (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://movements-journal.org/issues/04.bewegungen/14.korvensyrjae--valletta-process-westphalian-imaginary-migration-research.html

———, 2020, "Resumption of charter deportations from Germany to The Gambia. Exploring the integration – deportation nexus", Migration Control, 16 December 2020, (accessed 19 January 2022), https://migration-control.info/resumption-of-charter-deportations-from-germany-to-the-gambia-exploring-the-integration-deportation-nexus/

Lecadet Clara, 2017, "Accords de réadmission : tensions et ripostes", Plein droit, vol. n° 114, n° 3 : 15–18.

———, 2018, "Deportation, nation state, capital", Radical Philosophy, n° 2.03. (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/article/deportation-nation-state-capital

Odugbesan Abimbola and Schwiertz Helge, 2018, "“We Are Here to Stay” – Refugee Struggles in Germany Between Unity and Division", in Sieglinde Rosenberger, Verena Stern and Nina Merhaut (eds.), Protest Movements in Asylum and Deportation, Cham, Springer International Publishing : 185‑203.

Omwenyeke Sunny, 2016, "The Emerging Welcome Culture_ Solidarity instead of Paternalism", The VOICE Refugee Forum (Online). 1 May 2016. (accessed 19 January 2022) http://thevoiceforum.org/node/4155

———, 2017, "Refugees Welcome!!! – The Necessary but Missing Dimensions ", The VOICE Refugee Forum (Online). 5 April 2017. (accessed 19 January 2022). http://thevoiceforum.org/node/4348

Osa Rex, 2011a," Die Stimme der Unterdrückten – gegen falsch verstandene Solidarität", The VOICE Refugee Forum (Online). 16 November 2011. (accessed 19 January 2022). http://thevoiceforum.org/node/2318

(English translation: "The Voice of the Oppressed: Against Misunderstood Solidarity", http://cultureofdeportation.org/2021/12/10/voice/)

———, 2011b, "Rassistische Kollaboration mit dem Abschiebungsregime", Solidarité sans Frontières, n° 4.

Oulios Miltiadis, 2016, Blackbox Abschiebung: Geschichte, Theorie und Praxis der deutschen Migrationspolitik, 2. Edition, Berlin, Suhrkamp.

Pieper Tobias, 2008, Das Lager als Struktur bundesdeutscher Flüchtlingspolitik, Dissertation, Freie Universität, Berlin.

Poutrus Patrice G., 2019, Umkämpftes Asyl: vom Nachkriegsdeutschland bis in die Gegenwart, Berlin, Ch. Links Verlag.

Privacy International, 2020, "Here’s how a well-connected security company is quietly building mass biometric databases in West Africa with EU aid funds", (Online). 10 November 2020. (accessed 19 January 2022). http://privacyinternational.org/news-analysis/4290/heres-how-well-connected-security-company-quietly-building-mass-biometric

Sharma Nandita Rani, 2020, Home rule: national sovereignty and the separation of natives and migrants, Durham, Duke University Press.

TAZ, 2016, "Rede der Kanzlerin bei der Jungen Union: Merkel will konsequente Abschiebung", taz (Online). 15 October 2016. (accessed 19 January 2022). https://taz.de/!5348767/

The VOICE Refugee Forum, 2014, "Court Process against Rex Osa for participation in Nigerian Embassy action in Berlin", (Online). 24 March 2014. (accessed 19 January 2022). http://thevoiceforum.org/node/3519

Walters William, 2018, "Aviation as deportation infrastructure airports planes and expulsion", Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 44, n° 16.

Ziyal Yunus and Böhm Johanna, 2020, "Ungebetener Besuch von Männern in dunkler Kleidung", Hinterland, n° 45 : 15‑20. (Online, accessed 19 January 2022). https://www.hinterland-magazin.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Hinterland-Magazin_45-15.pdf

next...

Notes

30

1 In our German, European and Euro-African context, we refer to networks like the Alarm Phone Watch the Med, Statewatch, Border Violence Network, Alarme Phone Sahara, the Oury Jalloh Initiative, NSU Watch, The VOICE Refugee Forum, Caravan for the Rights of Refugees and Migrants, Afrique-Europe-Interact, International Women Space, Aktion Bleiberecht, No Border Assembly, Campaign for the Victims of Racist Police Violence (KOP), and many others. Further, analyses developed in the German research network kritnet (Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies) have greatly influenced our perspective.

2 See http://cultureofdeportation.org/. For the documentation of Yusupha Jarboh’s case, see http://cultureofdeportation.org/2017/06/01/file-yusupha-jarboh-in-germany-1994-2013/ and for Joseph Koroma’s case: http://cultureofdeportation.org/2017/06/01/file-joseph-koroma-in-germany-2006-2013/

3 Including Refugees 4 Refugees (https://refugees4refugees.wordpress.com/), Justizwatch (https://justizwatch.noblogs.org/), and other groups too numerous to cite.

4 Osa’s use of this term follows his engagement in struggles that have self-identified as the refugee movement. Its participants redefined the term refugee as an identity produced at the intersection of the German asylum system, European border regime, (post)colonial dispossession and resistance. Korvensyrjä agrees with this critique, but prefers the term asylum migrant, which emphasises the role of state practice (the asylum system) in producing categories of control after 2015, in a time when the use of refugee was reinforced as a fetishised and stigmatising socio-political term.

5 Omwenyeke (2016, 2017) analyses the paternalist and racist dimensions of the ”welcome culture“.

6 Senegal, Ghana, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia and Serbia.

7 Abschiebung: Forced removal after a negative decision or a deportation order. Deportations within six months of entry (Zurückschiebung), refusals of entry (Zurückweisung) or “voluntary“ deportations are not included. The figures in this section are drawn from parliamentary inquiries posed by Left party (Die Linke) members of Bundestag to the federal government between 2015 and 2020.

8 Reintegration and Emigration Programme for Asylum-Seekers in Germany/Government Assisted Repatriation Programme.

9 There is no comprehensive government data on the latter two groups.

10 The approach derives from the late 1970s and early 1980s (Pieper, 2008).

11 With the term “deportation chain”, The VOICE Refugee Forum refers both to the racially oppressive and the regime-like nature of deportation, spreading across different sites.

12 The German agency granting residence permits and organising deportations.

13 The existence of such a list was made public by the Spiegel in 2006 (Dahlkamp and Stark, 2006).

14 They can also be criminalised under § 95 of the German immigration law (Aufenthaltsgesetz) for “unauthorised residence without a passport” (usually with a fine, seldom with a prison sentence).

15 European Border and Coast Guard Agency.

16 http://cultureofdeportation.org/2017/06/01/file-yusupha-jarboh-in-germany-1994-2013/

17 http://cultureofdeportation.org/2017/06/01/file-joseph-koroma-in-germany-2006-2013/

18 See also Lecadet (2018).

19 http://cultureofdeportation.org/2019/07/19/charter-160719-muc-senegal/

20 https://afrique-europe-interact.net/1605-0-Gefesselt-als-Paket-nach-Mali.html

21 https://migration-control.info/resumption-of-charter-deportations-from-germany-to-the-gambia-exploring-the-integration-deportation-nexus/

22 Instead, a finger print match in the EURODAC database is mostly sufficient. This database is used to enforce the Dublin III regulation, which stipulates that asylum seekers must lodge their application in the European country of first arrival and not travel to a further signatory state.

23 https://alarmephonesahara.info/en/

24 For the Dublin deportation blockades in asylum centres in Osnabrück around 2014-2015, see Hinger and Kirchhoff (2019). Airport campaigning focused since early 2000s particularly on Germany’s largest aerial deportation hub in Frankfurt. Memorable and highly effective was the campaign Deportation Class, against deportations on Lufthansa passenger flights.

25 2017 Act to Improve the Enforcement of the Obligation to Leave the Country; 2019 Orderly Return Act.

26 https://www.aktionbleiberecht.de/

27 https://noborderassembly.blackblogs.org/deportation-alarm/

28 The Deportees Emergency Reception and Support, including people with migration experience: https://refugees4refugees.org/2019/08/30/deportees-emergency-reception-and-support-nigeria/

29 For a journalist report on the flight of 19th August 2019, see Refugees 4 Refugees, 2019.

30 The previous package with a similar aim was the 2017 Act to Improve the Enforcement of the Obligation to Leave the Country.

31 See Section I. The group was first called The VOICE Africa Forum, and later renamed.

32 A catalyst was the suicide of the Iranian asylum seeker Mohammed Rahsepar in Würzburg.

33 Abbreviated from Arrival, Decision, Return (Ankunft, Entscheidung, Rückführung).

34 Today few other states besides Bavaria, have renamed their first reception facilities as ANKER centres. In December 2021 the new federal coalition government announced the end of the ANKER as a federal model. However, the difference to regular first reception facilities is slight.

35 See for instance Culture of Deportation and Justizwatch (2018), http://cultureofdeportation.org/2018/05/07/bamberg/

36 Mostly defensive, against penalty orders which otherwise would have lead to conviction without a hearing.

37 The 2019 Orderly Return Act introduced the possibility to "enter“ (Betreten) camps to enforce deportations without a search warrant. On Alassa M.’s case in February 2021, the Stuttgart Administrative Court ruled that first reception facilities were not protected by the Article 13 of the Constitution, unlike other living spaces. Further, the court found that the Ellwangen first reception facility had been a "dangerous place“ during the police operation, see Culture of Deportation and Justizwatch (2021).

38 Browne (2015) calls such practices "dark sousveillance“.

39 We co-organised the workshop with Afrique-Europe-Interact and the AME at a conference of kritnet (Network of Critical Border and Migration Regime Research), May 26-29, 2016.

40 See also Alarme Phone Sahara’s monitoring of deportations from Algeria to Niger, https://alarmephonesahara.info/en/.

41 The concept Heimat (literally: homeland) carries a heavy historical baggage of nationalism and racism.

42 See Lecadet (2018) for a critique of “return”. The naturalising associations are also performed in the names of governmental programs, such as Perspektive Heimat by the German federal state or Coming Home, the “voluntary return” program of Munich, the Bavarian capital city.

43 This is the language, for instance, of the IOM program “Migrants as Messengers”, https://www.migrantsasmessengers.org/

44 Ibid.

45 English translation: http://cultureofdeportation.org/2021/12/10/voice/

Return to the beginning of the article...

https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/antiatlas-journal-05-korvensyrja-osa-deportation-monitoring-in-germany-and-nigeria-asymmetric-strategies-solidarity-and-activist-knowledge-production.pdf