antiAtlas Journal #01 - Spring 2016

Introduction: SCIENCE-ART Explorations AT THE BORDER

Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary, Jean Cristofol and Cédric Parizot

Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary is Professor of Geography at University of Grenoble-Alpes and member of the PACTE research laboratory (CNRS UMR 5194). She is member of the antiAtlas of Borders collective. Her most recent publications are: Qu'est-ce qu'une frontière aujourd'hui?, 2015, Paris, PUF and Borderities and the Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders, 2015, Palgrave Macmillan (co-edited with F. Giraut).

Jean Cristofol is Professor of Philosophy at the École Supérieure d'Art of Aix-en-Provence. He is member of the antiAtlas of Borders collective. His latest publication is: “Flux, stocks et Fuites”, in Locus Sonus, 10 ans d'expérimentations en art sonore, Éditions Le Mot et le Reste, 2015.

Cédric Parizot is Researcher in Anthropology at IREMAM (CNRS UMR 7310). He is initiator and coordinator of the antiAtlas of Borders project. His most recent publications are: Israelis and Palestinians in the Shadows of the Wall. Spaces of Separation and Occupation, 2015, Ashgate (co-edited with S. Latte Abdallah) and “Marges et Numérique/Margins and Digital Technologies”, 2015, Journal des anthropologues 142-143 (co-edited with T.Mattelart, J. Peghini and N. Wanono).

Translated by Caroline Mackenzie

Keywords: antiAtlas, science-art, co-production, critique, experimentation, introduction, mediation, performativity, politics, reflexivity, subjectivity, technology.

Trevor Paglen, Open Hangar; Cactus Flats, NV; Distance ~ 18 miles; 10:04 a.m., 2007

To quote this article: Amilhat Szary Anne-Laure, Cristofol Jean, Parizot Cédric, 2016, "Science-art explorations at the border", antiAtlas Journal 01 | 2016 [Online], published on June, 30th, 2016, URL: http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/01-introduction-science-art-explorations-at-the-border, DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.23724/AAJ.1 accessed on Date

I. Introduction

1 Creating a journal is a challenge. Launching the antiAtlas-Journal is a double challenge: it assumes that the web offers new and different formats for combining texts, images and other media and that this will renew our approach to borders. Borders are at the centre of our enterprise because, for us, they constitute an excellent opportunity for understanding the complexity of contemporary issues. Even though it has been scientifically established that borders are opening and closing at the same time, the most common representation of borders remains a line! Long perceived as a reality that is peripheral to our territories, they now constitute complex networks sorting and regulating flows and they profoundly intersect and influence our lives. More than any other political object, borders are simultaneously places and procedures that must be taken into account when analysing globalization and building up critical thought.

In order to better understand how borders operate, the antiAtlas of borders collective has, over recent years, sought to problematize the frames and formats we use to understand and study borders. Talking about an antiAtlas does not mean that we deny maps as a way of accessing the world, rather we envisage maps, like any other dispositive, as tools sustaining specific techniques of representation. Constituted over a particular period of history and in a European-centric context, this knowledge has strongly contributed to the construction of the reality that it pretends to grasp and depict: space, territories, borders, etc.Confronted with what we have identified as a crisis of representation, we offer a radical and critical rethinking of our representation of borders in the spaces we open (seminars, performances, conferences/exhibitions, Internet site) where researchers in human and hard sciences, artists, experts and inhabitants can confront their practices and experiences.

next...

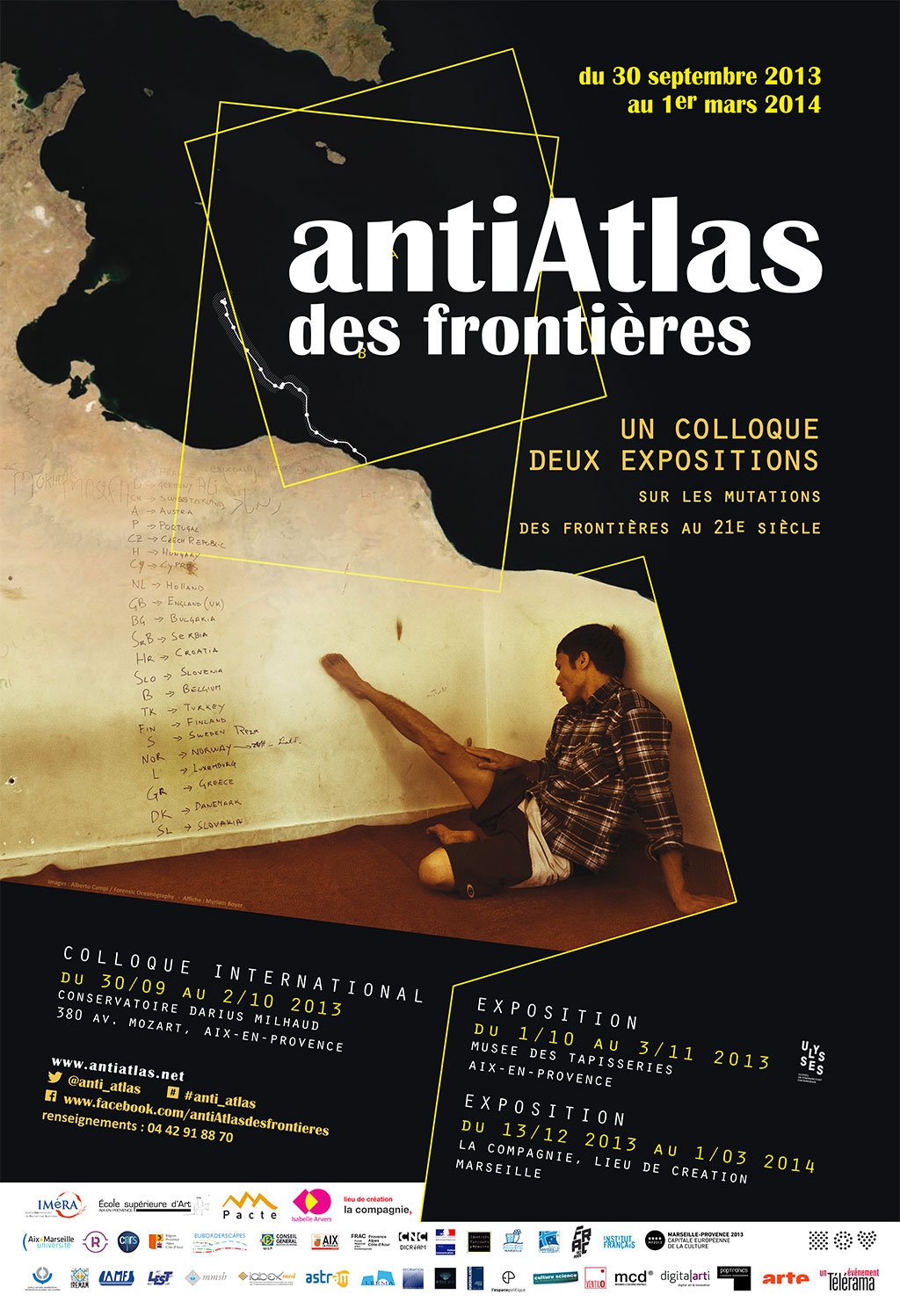

Affiche colloque et exposition antiAtlas des frontières, Aix-en-Provence 2013,

conception graphique Myriam Boyer, d'après les travaux de Alberto Campi et Forensic Oceanography.

Exposition antiAtlas des frontières #2, La Compagnie, Marseille, 2014, photographie Myriam Boyer

II. An exploratory digital space

2 Our journal seeks to extend this initiative by offering an exploratory editorial space that will allow authors and readers to share epistemic reflections on science/art experimentations in a dialogic manner. Establishing a corpus that brings together texts, images, video, sound, etc. will produce emotions and extend the performativity of the structures we conceive. We position ourselves as part of a process that sees aesthetics dissensus as a method for achieving political emancipation.

The creation of the antiAtlas-Journal is also motivated by the mitigated observations we have developed in the field of border studies. Over the last twenty years, an increasing number of academic publications and the creation of major journals (Journal of Borderlands Studies, Geopolitics – the first issue of which, in 1996-97, was called Geopolitics and International Boundaries, L’Espace Politique, etc.) have contributed to the development of a very rich field of research and has also encouraged multidisciplinary initiatives, i.e. the convergence of several epistemologies on a single object, though this has rarely generated borrowings and displacements between and within these various disciplines. Recently, new publications have sought to renew reflections within this field which is undergoing scientific consolidation. This is the situation for Movements, a new journal that takes a very critical approach bringing migration and flows at the forefront of border thinking. Throw out disciplinary categories, they will come back and hit you in the face: these new approaches to border studies are calmly circumscribing themselves institutionally.

Finally, the confrontation of contrasting productions, approaches and practices of researchers in humanities (anthropologists, political scientists, sociologists, economists, geographers, historians, jurists, etc.), in exact and experimental sciences (biometry, artificial intelligence, etc.), of artists (net.art, hackers, tactical geographers, artists, etc.), of experts (customs officers, industrialists, etc.) and of inhabitants (migrants or not, since borders cut through everybody) as carriers of a non-expert discourse, is all the more necessary as borders have become increasingly complex technological, political, economic and social objects. In other words, in addition to offering a critical reflexion, the antiAtlas-Journal aims to build on, and benefit from, the complementarity of knowledge and practices.

next...

Benoit Tadié, conférence-exposition antiAtlante delle frontiere, Festival Internazionale, Ferrara, 2014

Myriam Boyer, Ateliers de recherche antiAtlas, IMéRA, Marseille, 2012

III.

3The antiAtlas-Journal will seek to promote this transdisciplinary approach at two levels. Our journal will first give priority to contributions offering a critical reflection on sciences/arts explorations that relate to the mutation of contemporary borders in order to renew the ways we construct and think (geo)politics and to engage us in transforming our own methodologies. Throughout the editing and publication processes, we will prolong these experiments through the involvement of an artist whose work focuses on the confrontation of media and digital publishing: Thierry Fournier.

His involvement here draws on his experience as both artist and designer. Our intention is to establish a dialogue in the process itself of developing the journal, by not seeing graphics as a secondary feature for illustrating texts. The publishing process will constitute a significant initiative, creating an interplay of images, sounds and writings that will produce not only new forms, but also new meanings. Our objective is to give room for meanings to circulate, without deciding beforehand the institutional keys for interpretation or the hierarchy between texts and images, artworks and commentaries. This implies that the articles’ authors, the editorial team and the artist/designer will engage in a debate at the end of which the artist/designer will assemble the journal as a complex layout, proposing a gesture that responds to the elements he has been given. Our hope therefore is that these efforts will make it possible to produce innovative publication formats for human and social sciences.

In brief, each publication will constitute an editorial unity articulating text and media in order to generate creative disruptions. This confrontation of text, image and sound will contribute to the denaturalization of practices of representation in social sciences. The result will be performative in that it will extend the experimentation process between researchers and artists by the invention of a novel publication. The mediation of a third party, reader or spectator, to which this work is presented, will become a constitutive element in the dialogic construction of gaps between points of view, discourses and forms.

The result will be performative in that it will extend the experimentation process between researchers and artists by the invention of a novel publication.

By articulating texts and images, the antiAtlas-Journal will also open up further possibilities for writing and collaborating on articles. Co-signing an article of the antiAtlas-Journal implies different kinds of collaborations. It is the case, in this seminal issue, of the article on “Research art and video games: Ethnography of an extra-disciplinary exploration” produced by both Cédric Parizot and Douglas Edric Stanley. The former wrote the text as a first-person narrative in order to talk about his personal experience, while the latter concentrated on producing and editing images, videos and an interactive scenario. This type of contribution questions both the attribution of authorship within sciences-arts practices and the fact that the collaborative procedures to be demonstrated in each issue of antiAtlas Journal will often involve more people than found in the complete list of one paper’s authors. Our articles respect peer reviewing requirements in order to guarantee the quality of the journal’s contents, but our desire to remodel formats and styles will certainly require us to embark on a long-term reflection on this practice too!

next...

Amy Franceschini, Finger Print Maze, exposition antiAtlas des frontières, Musée des Tapisseries, Aix-en-Provence, 2013, photographie Dominique Poulain

Ken Rinaldo, Paparazzi bot, exposition antiAtlas des frontières, Musée des Tapisseries, Aix-en-Provence, 2013, photographie Dominique Poulain

IV. Pursuing the reflexions and experimentations carried out in the frame of the antiAtlas of Borders

4 This first issue of our Journal, Explorations and practices in sciences-arts at the border, seeks to demonstrate the heuristic interest of interactions between artistic practice and research in border studies. By bringing together contributions from authors who participated in our Collective’s activities, it extends the reflections and experimentations that we have initiated over the years of companionship through the seminars and conferences/exhibitions of the antiAtlas of Borders. Later issues will of course open up the antiAtlas journal to external contributors. The objective for everyone is to challenge research in terms of its formats and in terms of those through which experience is shaped as a sensitive and meaningful reality.

The three first contributions offer a general reflection, making it easier to situate the role of sciences-arts interactions in the history of research and of art. They provide a variety of viewpoints, their authors being researchers and/or artists: each in their own way bears witness to the fact that they have crossed this institutional border. Furthermore, they seek to deconstruct this dichotomy between sciences/arts, or arts/sciences, in order to rethink the way that these relationships have evolved. Reading them gives a much nuanced vision of these collaborations and a better perception of the different issues that these crossings and displacements represent. Altogether, we find ourselves better equipped for perceiving the political dimensions involved in the establishment of this type of relationship.

In his article, Jean Cristofol emphasizes that, until recently, sciences-arts interactions were seen as marginal adventures or hazardous speculations without any real impact. The development of information and communication, and notably digital technologies over the last thirty years has given them an acute importance. And with good reason, since, when combined with economic, social, cultural and political transformations, these technologies have not only challenged artists and scientists by confronting them with new mediums, but they also have radically modified interactions between the domains of industry, science and culture.

From his perspective, the question we must answer, through our studies of the relationship between arts and science, is not so much what role art can play within scientific practices, and reciprocally, but rather how these interactions reflect new configurations and linkages between domains that our cultures had, until recently, set as separate fields. The changing role of artists in society and their relationship with technique and sciences was already observed by several philosophers (e.g. Paul Valéry, Walter Benjamin, and John Dewey) and artists (e.g. Moholy-Nagy) during the first half of the 20th century. In revisiting their writings and some more recent works, Jean Cristofol re-examines the resolutely exploratory nature of artistic practices, which “engage our experience of an environment that has been profoundly transformed, appearing now as more technological driven and mediatized.”

next...

James Bridle et Einar Sneve Martinussen, Drone Shadow 002, Istanbul, Turquie, 2012.

Peinture blanche de signalisation des routes, 15 x 9 m.

5 To illustrate this point, Anna Guilló demonstrates how, over the last twenty years, artists have become massively involved in cartography as an area of research and of expression, building up a novel relational place. Focusing on the connexions between space and border, she shows how Border art, in the same way as experimental geography, has led to a redefinition of the limits of art as well as of the figure of the artist. Through the recurrent motifs of the map and the limit in contemporary art, she deflects attention away from the dominant plastic rhetoric and the ways in which artists, through their creations, question the status of the visible and the invisible and through which authors position themselves both internally and externally with regard to their work. She also explores these contradictions in the works she has herself created on these very themes and which punctuate her text. Inspired by the proposal made by the critic Brian Holmes, she suggests resorting to the sometimes misleading notion of ‘extra-disciplinarity’. This is indeed a tool that Holmes has made available to artists so that they can achieve their potential for emancipation that is offered by theoretical contribution. Accepting that art criticism no longer stands apart from creation allows art to challenge the borders that institutions and markets expect them to respect: these are the stakes involved in this term. Using it here is all the more interesting in that social sciences can easily adopt it more or less literally. Nevertheless, from an artist’s point of view, this proposal raises the ambiguous issues raised by open cooperation: working with concepts taken from other contexts or collaborating with the concept-makers themselves does not lead to the same processes.

In “Claiming the critical potential of arts-/social sciences experimentations. Portrait of the researcher as an artist”, Anne Laure Amilhat-Szary discusses the sciences-arts dynamic. In reviewing the specificity of collaborations between artists and social science researchers, she questions the now self-evident outcomes expected from so-called ‘art-science’ companionships. Denouncing the quest for innovation and its distortion by market dynamics, she attempts to demonstrate the aesthetic and scientific modalities for potential partnerships between these fields. She explains that it is high time for us to move away from an artificial binary (historically situated) view of arts and sciences and instead to question together, the status of research and thus succeed in producing a strong proposal: that the researcher can claim the status of an artist. Quite apart from questions about medium and conditions for a production, an opus, and a text, the key issue is to promote the need for a reflexive component at the heart of production of knowledge. Social sciences focus on topics that are not external to them and the concepts they create can be potentially used and transformed by the people they describe: for these reasons, they must now face up to the limits of their subjectivity. Approaching this theme via the notion of border, and in particular a mobile border, undoubtedly allows us to understand the possibilities available in the relationship that can exist between the worlds of art and science. Escaping from the reciprocal instrumentalization of arts by sciences and of sciences by arts allows us to produce together emancipatory devices that incite their audience to act through the sensitive relationship that they generate and their capacity to transmit fair ideas.

next...

V.

Ina Wudtke, Portrait de l'artiste en Chercheur (A Portrait of the Artist as a Researcher), installation, MuHKA, Anvers, 2006, photographie 414vzw, avec l'aimable autorisation de l'artiste.

6 The three following contributions adopt a more empirical approach, since each reviews the process of developing sciences-arts productions by treating the question of borders through three different mediums: an ethno-fiction film (Nicola Mai), a collection of participatory maps on paper and fabric (Sarah Mekdjian and Marie Moreau) and a video game (Cédric Parizot and Douglas Edric Stanley). These investigations were led either by a researcher/artist (Nicola Mai) or by a collective of researchers and artists, i.e. through co-productions. Although their objective is to explore new formats for modelizing research results, the authors do not however envisage that these mediums are more efficient than the dominant schemes used in social sciences or artistic practices today. Their commitment to these techniques is resolutely problematized. By playing on creative disruptions and on the displacements due to these experiments, they invite us to reflect on the interest that these new forms of research and creation really offer, while at the same time providing a critique of the formats currently dominating their disciplines and practices.

next...

7 Nicola Mai, in “Assembling Samira: understanding sexual humanitarianism through experimental filmmaking”, revisits his creative work in a video-documentary based on an ethnographic survey carried out among migrants who work in the sex industry. As part of a long survey, his film Samira explores in greater depth the case of a person who, at several periods in his life, crosses international borders from one side to the other while, at the same time, crossing gender borders. This is the second film in a trilogy focusing on deconstructing the figure of victim in sex work. Nicola Mai takes his so-called ‘mobile’ methods even further by building the film around a verbatim version of interviews he carried out in the field. In this film, as he plays himself, he penetrates his fictional world in order to offer a hybrid auto-ethnography. Accompanied by an iconography that admirably demonstrates the beauty of Samira, this article develops a complex reflexive questioning on the ways in which a research project can evolve when the researcher takes on the role of an artist. This approach allows him to produce extremely convincing evidence on the relationship between body and norms at the border, but also to propose theoretical perspectives on the evolution of the social sciences researcher’s physical presence within the structures he puts in place.

next...

Nicola Mai, Samira (installation), exposition antiAtlas des frontières, Musée des Tapisseries, Aix-en-Provence, 2013, photographie Dominique Poulain

8 In “Redrawing experience: Art, sciences and migratory conditions”, Sarah Mekdjian and Marie Moreau’s article takes the form of a duet as a homage to travellers, asylum seekers, and artistic and scientific collaborators with whom they produced a participative cartography work. Here again the key issue is not only scientific and aesthetic but particularly political. First, they explain their use of drawing as a tool for meeting in welcoming way while sharing information on migratory patterns. The underlying reason for this decision lies in their desire to avoid reproducing the violent situations that asylum seekers face in their compulsory interviews with administrative agencies during which their stories are checked in order to determine their legal status and their eligibility for the granting of identity papers. In order to engage in this counter-mapping, during which they aimed to stress more fully the fact that migrating cannot be subsumed to a journey across a section of the planet by tracing an arrow on a map, they invited asylum seekers to sketch out their wanderings. Using paper and fabric, the migrants were encouraged to outline not only their travels, but also their emotions throughout the journey: elements of their experiences of exile as they lived, understood and imagined them. Sarah Mekdjian suggested that they agree on a common key to the maps, as a way of linking these experiences. The results are fascinating because they document a multiple reality with so many nuances that stay-at-home citizens have difficulty understanding, and because they partially reinvent classic codes of migration maps, all the while raising new questions about the status of works produced in these workshops: are these maps? are they works of art? how can we account, in their production, for the asymmetric roles of asylum seekers, free-lance artists, and publically paid researchers? Sarah Mekjian and Marie Moreau present here another map that they drew together to describe their experience of co-production. Paradoxically, this last drawing invites us to lose ourselves in the labyrinth of their interrogations, no doubt to draw us into the debate on exploring the limits of art and science from the perspective of the individual’s commitment.

next...

Sarah Mekdjian, Marie Moreau et et Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary, Cartographies traverses, exposition antiAtlas des frontières, Musée des Tapisseries, Aix-en-Provence, 2013, photographie Myriam Boyer

9 Finally, in “Research, art and video games: Ethnography of an extra-disciplinary exploration”, Cédric Parizot and Douglas Edric Stanley come back to the process of conception and development of a documentary and artistic video game, A Crossing Industry, which they have developed in collaboration with Jean Cristofol and students from the École supérieure d’art d’Aix-en-Provence since 2013. The objective of A Crossing Industry is to give an account of an ethnographic field survey carried out in the south of the West Bank and Israel over several years by Cédric Parizot. By using a game simulator, Parizot and Stanley envisioned the modelization of different types of interaction between a wide range of actors (Palestinians and Israelis) interacting in the shadow of the Wall and influencing, each at their own level, the functioning of the separation system imposed by the Israelis on Palestinians between 2007 and 2010. The objective of this article is to analyse how video games can articulate an ethnographic approach together with an artistic approach which is animated by its own aesthetic and poetic stakes. Given that A Crossing Industry is still under development, this article does not seek to assess the game’s capacity to communicate a message to a specific public, but rather to understand what this form of science-art experimentation means for its conceptual designers. Considering their collaboration through the concepts of artistic dispositive and of critical documentary, they discuss the issues raised by the gaps between their approaches and propositions. We can situate the game’s input within this inter-subjectivity (documented by the researcher through a reflexive process which he could only analyse as the project progressed). In fact, this analysis has no real pretentions of contributing to the debates on Games Studies; it is, above all, an exercise in extra-disciplinarity, in the sense defined by Brian Holmes (2007) which is of interest, in the first instance, to anthropology and artistic creation.

These three works, Samira, Crossing Maps and A Crossing Industry function somewhat like tactical media: they do not only produce an alternative and critical discourse on social, economic or political processes at borders, they also encourage us to undertake a critical review of our methods of access and construction of reality, both in the artistic practices and in social sciences research.

Notes...

Exposition antiAtlas des frontières #2, La Compagnie, Marseille, 2014, photographie Myriam Boyer

Colloque-exposition The Art of Bordering, Maxxi, Rome, 2014, photographie Myriam Boyer

Notes

10

1. Launched in 2011 by the Institut méditerranéen de recherches avancées de Marseille (IMéRA), this project has led to the cration of a collective of researchers, artists and experts which is supported by the Institut de recherche et d’études sur le monde arabe et musulman (IREMAM, CNRS/Aix Marseille Université), the École supérieure d’Art d’Aix-en-Provence, the PACTE research laboratory (CNRS/Université de Grenoble-Alpes) member of the EU Consortium (FP7) EUBORDERSCAPES, and the LabexMed Project. It published its theoretical manifesto in 2015: The antiAtlas of Borders, A Manifesto, DOI:10.1080/08865655.2014.983302.

2. Less used than its antonym, ‘consensus’, the term ‘dissensus’ expresses the diversity of opinions or of methods of feeling or judging. Identified by social psychology (Moscovici, S & W. Doise, 1992, Dissensions et consensus. Une théorie générale des décisions collectives, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 296 p.), use of the term was to have a great success in the works of J. Rancière which place the aesthetic relationship at the heart of political mechanisms: see in particular Le Partage du sensible : Esthétique et politique, 2000, Paris, La Fabrique and Dissensus. On Politics and Aesthetics, 2010, New York, London, Continuum.

3. http://www.antiatlas.net

4. http://movements-journal.org/issues/01.grenzregime, posted online in 2015, consulted 20/3/2015.

5. Jean Cristofol, article in this Journal, paragraph 3.

6. On the definition of this term, cf. the articles by Cédric Parizot, Sarah Mekdjian et Marie Moreau and Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary.

7. “Although the word ‘tropism’ adequately expresses the need or the desire to turn towards another object, here an external discipline, the notion de reflectiveness indicates a critical review of the point of departure, which seeks to transform the initial discipline, to take it out of its context, to open up new possibilities of expression, analysis, cooperation and commitment within itself. This two-way movement, or rather this transformative spiral, is what we can call extra-disciplinarity.”

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/01-Amilhat-Szary-Cristofol-Parizot-introduction-science-art-explorations-at-the-border.pdf