antiAtlas Journal #01 - 2016

Border art AND BORDERS OF art,

An extradisciplinary approach

Anna Guilló

Anna Guilló is artist and Professor in Art and Art sciences at University of Paris 1 Panthéon–Sorbonne. Co-founder of the La Fin des cartes? collective and member of the antiAtlas of Borders collective, she is head of the art and aesthetics journal Tête-à-tête.

Translated by André Crous

Keywords: art, artists, borders

James Bridle and Einar Sneve Martinussen, Drone Shadow 002, Istanbul, Turkey, 2012.

To quote this article: Guilló Anna, 2016, "Border art and borders of art, an extradisciplinary approcach", antiAtlas Journal, 1 | 2016, [Online], published on June 30th, 2016, URL : http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/01-border-art-and-borders-of-art, DOI : http://dx.doi.org/10.23724/AAJ.7 accessed on Date

1In a recent article, recapping the main thrust of their book, Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor (Mezzadra and Neilson, 2013), Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson argue that the contemporary debate around borders is infused with “a sense of cartographic anxiety” (Mezzadra and Neilson, 2012). Beyond the obvious relationship between cartography and borders, the authors echo the thoughts of Etienne Balibar by pointing to this anxious relationship with the border line and the instability of contours. Maps are representations open to critical thinking, changeable and animated by the more or less documented projection of multiple ways of materialising political borders and the isolation of territories: walls, fences, no man’s land.

For the past 20 years, artists have responded to this cartographic anxiety – the positivism having made way for a projective reading nourished by a geographic imaginary infused with a culture of geo-localisation if not of a domestic practice of GPS authorising a form of scepticism – by making significant investments in the field of cartography as a field of research and expression.

Since the cave paintings of Lascaux, where some specialists have identified the first attempts at cartography, the art of drawing has served practical and ideological purposes rooted in a desire to represent the earth and sky. The map is an artefact through which the imaginary gives shape to territories and stakes out the contours of a purely subjective if not reconstructed reality. The history of geography has therefore been marked, up until this day, by these artistic imaginaries at work in the representation of space. In a contemporary approach to cartography as a mode of representation of space, perhaps one should make distinction between that which is part of production (by using the dynamic term “mapping”) and that which refers to a more static form, “cartography”.

The map is an artefact through which the imaginary gives shape to territories

For the appearance and the rapid development of cartography in current artistic endeavours, one can find multiple origins: a) starting from the 1960s, the decompartmentalisation of artistic practices with the emergence of performance, video art, net art and digital art more generally; b) the gradual shift of the visual arts from belonging to a system of fine arts towards a form of expression belonging to the human sciences; c) the appearance of geo-criticism and the invention of Edward Soja’s thirdspace in 1996; and d) the increasing power of feminist, post-colonial and, more recently, decolonial studies (Quirós and Imhoff, 2012: 15).

next...

2 This context, which favours the emergence of a geo-history of otherness, has seen the birth of experimental cartographies thanks to the combined actions of artists and university researchers from all fields. We will examine a few examples. It is not necessary to move in the direction of map or border aesthetics, which is still very prevalent, especially in the field of contemporary painting (Harmon and Clemans, 2009), nor even of investing in the highly represented field of arts–sciences transdisciplinarity, but rather of trying to reach a breakthrough with respect to extradisciplinarity, as Brian Holmes defines it. At that point, one would understand that cartography as we see it today is a tool that brings with it the criticism of its own place of thought, whether it comes from the world of art, research or political action in the field. Thus, it could help us to understand some of the principles of epistemological anarchism (Feyerabend, 1979).

next...

I. Icon and index

3 On the border between art and knowledge, the map – a tool for explorers and conquerors that is informed today by an incommensurable strategy of producing aerial images – remains an inherently abstract drawing that is a representation of a three-dimensional, spherical world on a flat surface. As a monad of the world, it is both visible as and legible for the purpose of being a representation of something invisible that nevertheless exists. Thus, this image-simulacrum, the vehicle of a potential voyage, opens up not only to the real world but also to the world that is imagined to be possible. If the map has meaning, and thus it obtains status as an index, it is also an icon, as it maintains an analogue relationship with its referent (Tiberghien, 2007).

It is no longer possible to count the number of people who have drawn maps, but one can nonetheless try to draw a distinction between two main categories of production: On the one hand, there are those for whom a map is a priori a fact – in other words, the cartographic projections that geographers have drawn over time have become a motif that is appropriated in order to produce pictorial, graphic, woven or set variations, among others. On the other hand, there are categories for which the vocabulary of cartography is repurposed, twisted, reinvented and where, for example, the borders that demarcate countries and continents are shifted in order to produce critical maps whose political meaning has to be deciphered and, in one way or another, propose another perspective on the situations than that which the cartographic nomenclature has reported and codified.

The first category essentially concerns a poetic, aesthetic, even aestheticising vision of cartography. Although the two are not mutually exclusive, the second puts forward a manifestly more critical approach in the field of geopolitics. Even if the line between these two big categories is porous, it marks that which still distinguishes the modes of disseminating art: the art market, galleries, museums and traditional exhibitions on the one hand, and the Web, digital art, video performance, aerial images and “artivism” on the other hand. On the one hand, therefore, practices that have incorporated cartographic projections as they have been dictated for centuries, and on the other hand, tools seeking to decolonise the mental framework that was the outcome of the Westphalien system.

next...

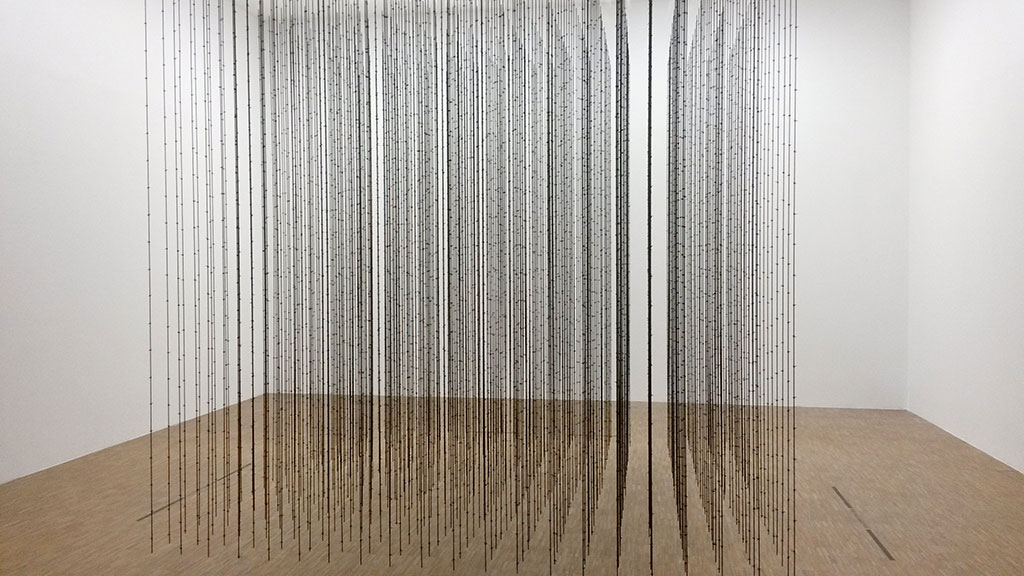

4 The cartographic works of Mona Hatoum, many of which were on display during her retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 2015, are rather representative of this porosity and the relationship with works that emerged from the plastic rhetoric of contemporary art rather than the context and the means of mediating them. Born in Beirut to Palestinian parents, Mona Hatoum moved to England when she was 23 years old, at the same time the war erupted in Lebanon, and has been creating multifaceted works for many years. Her works includes performances, sculptural objects, drawings and installations that have visibly non-apolitical themes. Her maps, whether they take the shape of a carpet devoured by mites, a globe of neon-red tubes, maps cut up into pieces, or a simple backing of glued cotton, all convey the insecurity of borders or the fake assurance from Western authorities who have known, throughout the centuries, how to impose the Mercator projection. By contrast, she often prefers Peters’s proportional version, which no longer pretends that Europe is the centre of the world. Faced with a work like Map (1999) [Fig. 1], an immense world map consisting of hundreds of glass marbles placed on the ground and put in motion by the vibrations of this backing when it is stepped on, it is impossible not to be fascinated by the spectacle of a work that, while it explicitly materialises the moveable character of borders and the fragility of a certain representation of the world, is above all a visual spectacle whose aesthetic emotion, reinforced by the staging, is unquestionably spectacular. The maps, by virtue of their plastic qualities and in the way in which they have been moved around inside the setting of the museum, have the power to thrill us, in the sense that we feel ourselves being uplifted. Mona Hatoum herself mentions the difficulty of being labelled an engaged artist and of seizing this opportunism that led her to create, for example, in 1988 during the First Intifada, also known as the “War of Stones”, a piece made of numbered stones. Ever since, she has moved the fields of her artistic practice towards the production of objects that are less openly political. It is nonetheless obvious that, in the hands of Mona Hatoum, a piece like Impenetrable (2009) (an allusion to Soto’s Penetrables, whose suspended resin rods take the form of barbed wire in Hatoum’s piece) is as effective at talking to us about borders as it is at conveying a critical approach towards the world of art, its self-referential practices, its institutions, its history and its limits. [Fig. 2]

next...

Fig. 1 : Mona Hatoum, Map, 1999

Transparent 14mm glass beads of variable dimensions.

The installation as seen at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris as part of the artist’s retrospective, June 24–September 28, 2015.

Fig. 2 : Mona Hatoum, Impenetrable, 2009

Barbed wire, fishing line, 300 x 300 x 300 cm.

The installation as seen at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris as part of the artist’s retrospective, June 24–September 28, 2015.

5 While artists have attempted to address (albeit not without difficulty) this frequent dilemma of being stuck between the obscenity of using politics as an artistic theme and the desire to participate in the public debate by means of their works, some thinkers and creators tackle the question by shifting their work towards the field of humanities in order to free themselves from the art market’s value system of objects and institutions.

A new figure is drawn of an artist who is no longer transdisciplinary but extradisciplinary

One could cite here the example of Trevor Paglen, who defines himself as an artist and a geographer. He works to define the limits, sometimes blurred, and the bridges between contemporary art, social sciences and other disciplines that are even farther removed in order to expand unusual and meticulous research protocols to interpret the world that surrounds us. Regarding his participation in the activities of the Critical Resistance collective, he clearly formulates his position as follows: “I make a distinction between this work and my ‘artistic’ work because I don’t want to put them on an equal footing or ask someone to do something other than what they do well in their own field. Many works of art are totally useless (in the practical sense of the word) for activists or with respect to the efforts made to change policies or whatever. By contrast, there are many tools that are extremely useful to activists but have virtually no artistic value. I think a lot of artists become dishonest and even disappointed with themselves when they try to connect these different elements in the same body of work” (Bhagat and Mogel, 2008: 41). Thus a new figure is drawn of an artist who is no longer transdisciplinary but extradisciplinary – a point to which we will return.

next...

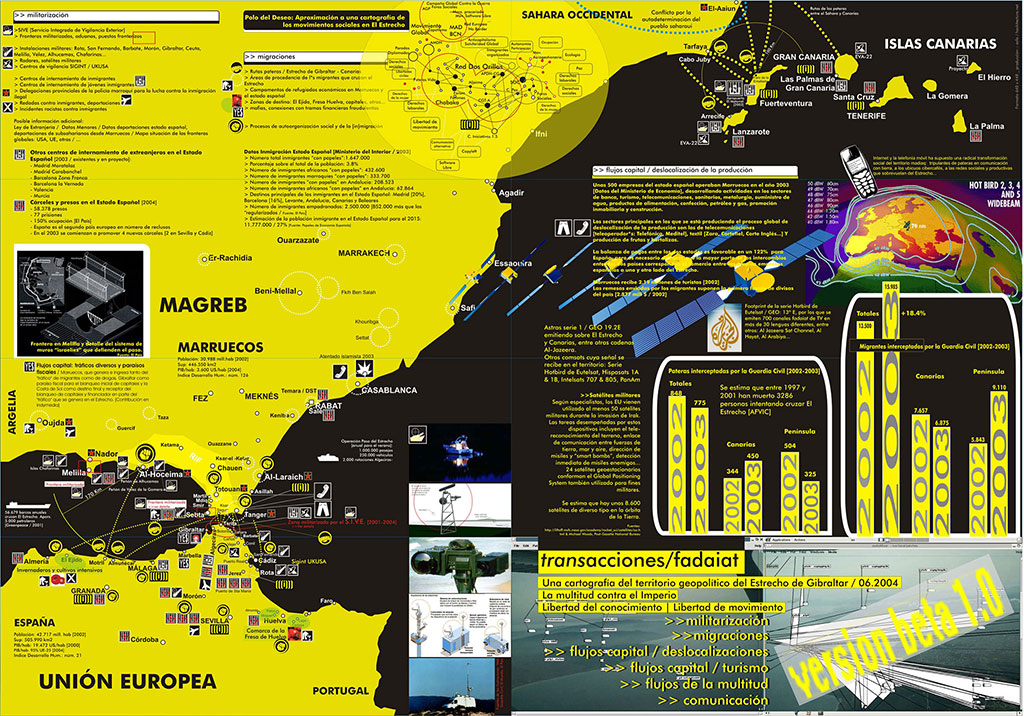

6 It would seem that in the age of networks, the immediacy of information, the dissemination of images in real time and migratory movements that are unequalled since the exodus following the Second World War, the mappers’ productions are without a doubt among those that make the most sense today, which does not exclude them from the aesthetic sphere but on the contrary means their belonging to the world of art is of secondary importance. This move could incorporate the actions of alternative cartography, radical cartography or experimental and critical cartography that often have much in common with each other and are still in opposition with the first category of artist cartographers, led by collectives of artists, architects, urbanists, philosophers, geographers, computer scientists, etc. Beyond the historical examples directly inspired by situationism, one will think of the recent actions of Stalker, Multiplicity, Visible Collective, OUCARPO, the Institute for Applied Autonomy, the Bureau d’études, BAW/TAF or Hackitectura. In fact, one of the latter’s maps, shown as part of the AntiAtlas of Borders collective’s exhibitions, has attracted particular interest: the Critical Cartography of the Strait of Gibraltar (2004) [Fig. 3]. Its choice of colours and its orientation lead to an exercise in mental gymnastics: The sea is a wide piece of solid black, while the land is yellow. Spain is at the bottom of the map, while the Maghreb is at the top. Furnished with a sturdy assortment of legends, this map puts forward keywords like militarisation, migration, capital exchanges, delocalisation and tourism, population flow and communication. The long list of items listed include SIVE (Sistema Integrado de Vigilancia Exterior), militarised borders, customs and checkpoints, military installations, military radars and satellites, the SIGINT and UKUSA surveillance centres, immigrant internment centres, immigrant youth internment centres, provincial delegations of the Moroccan police force fighting illegal immigration, immigrant raids, racist incidents against immigrants, other internment centres under the authority of the Spanish state (Madrid Moratalaz, Madrid Carabanchel, Barcelona Zona Franca, Barcelona La Verneda, Valencia, Murcia), the number of prisons and prisoners held by the Spanish state (77 prisons, 58,378 prisoners, at 150% capacity), the flow of capital, including tax havens and money trafficking, as well as sea routes used by the migrants’ small vessels and the encampments of economic refugees in Morocco and Spain: in El Ejido, Fresa Huelva, capitals, other mafias, connections with fraudulent financial networks… Many kinds of information are recorded about the nature of the exchanges that can be established from one bank/shore to the other, in particular by means of social networks and connections via cell phone. What is unique about this kind of map is that, as Maribel Casas-Cortes and Sebastian Cobarrubias note, it does not “reproduce the border as a place of separation but rather as a site of connection and of reciprocal flows that cross the Mediterranean” (Casas-Cortes and Cobarrubias, 2008:61). Thus, even if it is indisputable that the Mediterranean Sea forms a natural border, the Hackitectura group uses these geographic zones, like the Strait of Gibraltar, to create a cartographic representation of the type of interpenetration that can have the anxiety-inducing character indicated above.

Here, without making its status ambiguous, the map still reflects the plastic qualities that create the willingness to produce an object of visual communication imbued with geopolitical importance. Everything invites us to reconsider the North-South polarities and the interactions related to the situation as we know it. The open use of cartographic codes (base map, code colour, pictograms, ideograms, legends) produces an image that is no longer unambiguous but a visual contribution, by virtue of the specific means proper to the plastic language and to geopolitics. This cognitive gain has as much to do with the doubly critical register of the statements (geopolitical statements made on the cartographic image) as it does with the conceptual depth of a visual mode of expression that has no equivalent in written form and lets the subjectivity of the author operate as that of a recipient.

next...

Fig. 3 : Hackitectura, Critical cartography of Gibraltar, 2004.

Digital image:

http://www.antiatlas.net/blog/2013/08/14/cartographie-critique-de-gibraltar-hackitectura-2004-espagne

II. Texture of images, materiality of walls

7 With regard to a video by Ursula Biemann, filmed exactly at the moment when the Swiss artist, on the premises of the VideA collective, was informed and subsequently present at the police’s brutal dislodgement of a thousand Kurds living on an open field, Brian Holmes writes that: “what the artist adds to geographic research is an inquiry into the texture of the relations that produce the videographic space itself – a dialogic space rich in differences but also uncertain and partially opaque for its actors” (Holmes, 2007a: 112-113). One could say the same of Til Roeskens’s projects and more generally of the actions linked to the geo-history of otherness. The question of texture is one that is inherently plastic, sensorial. At a time when the means of disseminating the flows of information act (by smoothing) on images whose iconographic register it is no longer possible to discern, the work of artists contributes to making visible a world whose surplus of visibilities ends up blinding us. A form of metaphorical re-materialisation of the real can operate through the works, beyond the images or the border lines marked on a map [Fig. 4], which gives expression to this “caricature of the closed border” (Amilhat Szary, 2015b), these blocks of concrete, this mined berm, these flayed bodies on the barbed wire, these fingerprints that are burnt to erase an identity [Fig. 5] and these bodies that were hindered and drowned.

next...

Fig. 4 : Anna Guilló and Frédéric Leval, Les Sirènes de Schengen (The Schengen Mermaids), 2016.

Video 8 min. Soundtrack: overlay of 26 national anthems of the countries comprising the Schengen Area, Book 12 of Homer’s Odyssey read in ancient Greek by Maria Stavrinaki.

Fig. 5 : Anna Guilló, Calais 2, 2010

Dessin à la souris sur image satellite, tirage lambda sur Dibond, 100 x 60 cm.

8 It is in the context of the separation of two countries, and then of the building of the wall dividing Mexico and the United States, that the Taller de arte fronterizo collective was born between San Diego and Tijuana in the mid-1980s. Its ringleader, the Chicano performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña, left the collective four years later to establish the La Pocha Nostra organisation, an international troupe of performance artists that also functions as a logistics platform for all sorts of artistic projects. No longer focused solely on the question of geographical borders and the production of works on the line dividing the two countries, the group looked at the issue of “interior borders” that each of us carries without ourselves (genre, sense of community, culture, language…). La Pocha Nostra represents a very specific stream of performance art that ended up setting a precedent and leading the way for plastic artists to use “border art” (Gómez-Peña and Sifuentes, 2012). The work tackles, among others, the importance of learning as a place to think critically about the aesthetics of borders, and it distinguishes itself very clearly from the artistic interventions on the walls themselves or in the framework of the many artist residences that are offered today around this question.

But even the ultra-radical nature of an artist such as Guillermo Gómez-Peña, who nonetheless receives invitations from museums around the world, cannot escape the paradoxes that he himself denounced when he left the Arte fronterizo workshop, which, according to him, contributed to bringing the border to the centre instead of transforming the fringes into the centre (Amilhat Szary, 2015a:6). Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary has also underlined the contradictions of certain artistic statements on both sides: “But paradoxically, at the border itself, art also contributes to an increase in social inequality. In fact, during this period, one sees, on the American side, the exhibition space of the works of border art moved from the Centro de la Raza, a Chicano cultural site in the city centre, to the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, situated in the swanky northern suburbs. At the same time, on the Mexican side, the Centro Cultural Tijuana (Cecut), founded in 1982 and expanded and renovated in 2008, takes part in this promotion via several alternative sites (like the Casa del Túnel, an art space in a house that was formerly used for smuggling) that are little – if at all – connected to U.S. institutions” (Amilhat Szary, 2015:7).

Which theory of contradictory realities should be elaborated, then, to understand the role that artists play in this context of social and political activism?

One could agree that an issue as hot as that of borders necessitates something other than the contribution that artists make through their works. And yet, it must be recognised that a large number of multidisciplinary research programmes today regarding the question of borders have an artistic component to them and that the idea of value being added because of the specificity of the register of thinking and of the production of the field of creation is often the order of the day.

next...

III. The extradisciplinarity

of the art of borders

9 Following Habermas’s suggestions in Knowledge and Human Interests (Habermas, 1979), Michel Foucault makes a distinction between three types of techniques in human sciences: techniques of production, techniques of signification and techniques of domination. It appears rather clearly that the artist’s activity derives from the techniques of production and of signification, and it is not difficult to understand why Foucault, seeking to retrace not a philosophy but rather a genealogy of the subject, became interested in the third technique – the one that makes it possible to determine the conduct of individuals, impose certain wills on them or more generally to make them submissive. It is understood that that borders, insofar as they are effective systems, belong in equal measure to this third category, as do maps in their historical sense.

Border art, by means of the new aesthetic approaches through which it captures these questions about the relationship with space, shakes up the representations of what makes art (in particular, by bypassing the form of the map) by promoting that which brings it closer to experimental geography: its extradisciplinarity. In an issue of the journal Multitudes, devoted to institutional criticism, U.S. philosopher Brian Holmes recalls how art in the 20th century often “borrowed” the tools of its own reflection from other disciplines (psychoanalysis, philosophy, literature, etc.) by importing them into its own space: the institutional white cube. Today, these loans are still the order of the day in theoretical-practical fields such as bio-art, net.art, database art, etc. However, these practices seem to obey the same habitus of art’s self-reflexivity that ingests exogenous devices to put them into its own hands and serve the egocentric logic of the art world. And even when artists have tried on their own to follow the path of a possible theoretical emancipation, whether it be in the 1960s with the artists of Daniel Buren’s generation or in the 1980s with artists like Andrea Fraser, they failed because their discourse was not heard outside the field of art, and because institutional criticism, such as artistic (so-called independent) criticism, has this capacity to identify, accept and push this path aside in order to modify its centre of gravity and let a Daniel Buren or a Marina Abramovic into the circle of “established” artists.

To support his thesis, Brian Holmes looks to the Nettime project, which criticised the Internet by using its language and tools and directly shaped the development of the Web, a field that subsequently turned society upside down, but whose goal was “[to effect] change in the discipline of art (considered too formalist and narcissistic to escape its own charmed circle), in the discipline of cultural critique (considered too academic and historicist to confront the current transformations) and even in the ‘discipline’ – if you can call it that – of leftist activism (considered too doctrinaire, too ideological to seize the occasions of the present).” (Holmes, 2007b:13).

Thus, in this game of back and forth between an exterior discipline and critical reflection about an initial discipline, which results in a “transformative spiral”, extradisciplinarity criticises the cult of transdisciplinarity as well as that which Holmes calls the “indiscipline” – a result of the upheaval of 1968. According to him, they work together to prevent any in-depth research.

Building on the work of Eyal Weizman, Holmes defines extradisciplinary artists as follows: “The extradisciplinary ambition is to carry out rigorous investigations on terrains as far away from art as biotech, urbanism, psychiatry, the electromagnetic spectrum, space travel, etc., to bring forth on those terrains the ‘free play of the faculties’ and the intersubjective experimentation that are characteristic of modern and contemporary art, but also to identify, inside those same domains, the spectacular or instrumental uses of processes or artistic inventions, in order to criticise the original discipline and contribute to its transformation” (Holmes, 2007b:14).

next...

10 Generally speaking, artists share with the human sciences the ability to interpret a space; but above all, they know how to create a space. Extradisciplinary artists shift their skills towards other kinds of contributions, as one can observe, for example, in certain artistic projects around the question of drones and the spaces that they fly over, scrutinise, record, destroy and reconstruct for civilian or military purposes. Initially conceived of for strategic purposes for the armed forces, drones kill hundreds of “targets”, however badly identified, with impunity. These attacks that soldiers launch from afar are directly linked to video games but also, more generally, to a dystopian world that has for a long time digested Bentham’s Panopticon and Guy Debord’s society of the spectacle. Several contemporary artistic practices incorporate the images produced or conveyed by these instruments of a new cartography that are the photographs and films produced by drones. This new modality of investigation and collection of the real is a motivating factor behind the work of some artists and thinkers (Trevor Paglen, James Bridle, George Barber, Grégoire Chamayou (2013), among others) who have made use of this practice over the past decade to reveal the imagery of a world under surveillance and to form a critical point of view about these devices that are as indiscreet as they are invasive. And yet, it is precisely because the power of these ultra-technical devices inheres in their invisibility that it seems important that the artisans of the real reflect on, appropriate and – why not? – develop counter-devices (Samy Kamkar, Adam Harvey, etc.) to prevent this “everywhere war”, in the words of Derek Gregory (2011), from taking place while our eyes are turned away.

Every week, as part of a project dubbed “Dronestagram” [Fig. 6], James Bridle publishes aerial images taken by drones around the world. The artist posts the images on Twitter and Instagram to show that, despite the Internet and its mass of posted photos, the essential is often invisible. However, on the ground, he adds enormous white shadows to give these pilotless planes a presence in the city and an authentic visibility (Drone Shadow) [Fig. 7]. Trevor Paglen also highlights the issue of stealth in his photos of cloudless, or nearly cloudless, skies: Here and there, it is possible to make out a small black dot that at first might appear like a speck of dust on the image but is, in fact, a drone captured by the camera’s lens following many long hours of waiting in patience [Fig. 8]. In an entirely different format, in his Black Sites (2006) project [Fig. 9], he reveals, after lengthy field investigations, the presence of CIA prisons based in Afghanistan meant to receive kidnapped prisoners from around the world as part of the CIA’s “rendition programme”. This programme authorises the U.S. government to detain strangers suspected of terrorism in prisons situated outside the national territory, where federal laws do not apply, at least not insofar as the possibility of carrying out interrogation by torture is concerned.

next...

Fig. 6 : James Bridle, Dronestagram, 2012-2015

October 7, 2014: Two or three missiles hit a house reportedly belonging to an alleged Taliban commander, Mustaqeen. 4 to 7 people were killed; it is not know [sic] whether Mustaqeen was present or a casualty.

#drone #drones #pakistan (at Shawal Valley, South Waziristan) 10:34 am, 13 October 2014, 5 notes

All reports from The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and other confirmed sources. Also on Instagram and Twitter.

More information: http://booktwo.org/notebook/dronestagram-drones-eye-view | http://dronestagram.tumblr.com

Fig. 7 : James Bridle and Einar Sneve Martinussen, Drone Shadow 002, Istanbul, Turkey, 2012.

White paint indicating the routes, 15 x 9 m.

Fig. 8 : Trevor Paglen, Untitled (Reaper Drone), 2010 C-print, 121,92 x 152,4 cm.

Fig. 9 : Trevor Paglen, Black Site, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2006.

C-print, 60,96 x 91,44 cm.

IV. Towards the production of new spaces

11Trevor Paglen is an artist but also a geographer and a theoretician. His act of bringing together geography and art is related to the production of a space but also to the nature of the questions that geography poses, via its multiple methodologies, to art. Here, we witness the shift of the boundaries of art thanks to the nature of the questions that he asks. Trevor Paglen explains that “Instead of asking ‘What is art?’ or ‘Is this art successful?’ a good geographer might ask questions along the lines of ‘How is this space called “art” produced?’ In other words, what are the specific historical, economic, cultural, and discursive conjunctions that come together to form something called ‘art’ and, moreover, to produce a space that we colloquially know as an ‘art world’?” (Paglen, 2008:30)

Thus the issue is no longer only about reflecting on a space (a border, for example) but to ensure that the production of this reflection itself generates a new space.

Trevor Paglen defines experimental geography as being relevant to “practices that take on the production of space in a self-reflexive way, practices that recognize that cultural production and the production of space cannot be separated from each another, and that cultural and intellectual production is a spatial practice.”

One understands what a reflection such as this one owes to Walter Benjamin’s text, The Author as Producer (Benjamin, 2003), in which the German philosopher (who, within an entirely different historical context, attacks the stream of New Objectivity) defends the idea that an author cannot be satisfied with mastering only the content of his texts if the spaces in which the latter are disseminated are in the hands of institutions whose acts and opinions contradict the content of these very texts. Beyond these questions of form and substance, Benjamin recalls that social relations are conditioned by the relationships of production.

In this sense, the productions that are extradisciplinary – not transdisciplinary – and that we have barely caught a glimpse of here, facilitate a better understanding of how artists make use of the question of borders and how, in turn, this newly created space redefines the borders of art and the figure of the artist. From this extradisciplinarity, I would gladly turn to contemporary research focused on the “decolonialisation of knowledge” – the paradigm shift that follows post-colonial studies and the study of genre, whose goal is to deconstruct the national origins of knowledge – that is essentially based on Western, and thus colonial, predominance in line with Walter Mignolo’s epistemic disobedience (Mignolo, 2015).

Thus, what is at stake in extradisciplinarity is as much a matter of the willingness to decompartmentalise disciplines as it is to abandon the objects of study for other methods, other languages, other heterodox and a priori ineffective points of view in the expert’s opinion. Another form of logic is required here, and, instead of leading us to a better understanding of the why of an artist’s choice of a subject, it must guide us to consider the reasons why art appears to be such an effective context in which to talk about borders.

bibliography...

Bibliography

12

Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure, 2015a, « Le Border Art fait le mur », De ligne en ligne n°18, revue de la BPI du Centre Georges Pompidou, octobre-décembre.

Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure, 2015b, « Redéfinissons les frontières », Libération, numéro « Le Libé des géographes », 30 septembre. http://www.liberation.fr/monde/2015/09/30/redefinissons-les-frontieres_1394508

Benjamin, Walter, 2003, « L’auteur comme producteur », trad. par Philippe Ivernel, Essais sur Brecht, Paris, La Fabrique.

Casas-Cortes, Maribel et Cobarrubias, Sebastian, « Drawing Escape Tunnels through Borders. Cartographic Research Experiments by European Social Movements », Atlas of Radical Geography, Los Angeles, Journal of Aesthetics and Protest Press, 2008

Chamayou, Grégoire, 2013, Théorie du drone, Paris, La Fabrique.

Feyerabend, Paul, 1979, Contre la méthode. Esquisse d’une théorie anarchiste de la connaissance, trad. (anglais) par Baudoin Jurdant et Agnès Schlumberger, Paris, éd. du Seuil, coll « Sciences ».

Gómez-Pena, Guillermo et Sifuentes, Roberto, 2012, Exercices for Rebel Artists. Radical Performance Pedagogy, Oxford, Routledge.

Gregory, Dereck, 2011, « The Everywhere War », The Geographical Journal, Vol. 177, septembre, p. 238-250.

Habermas, Jürgen, 1979, Connaissance et intérêt, Paris, Gallimard, « Tel ».

Harmon, Katharine et Clemans, Gayle, 2009, The Map as Art. Contemporary artists explore cartography, New York, Princeton Architectural Press.

Holmes, Brian, 2007a, « Géographie différentielle. B-Zone : devenir-Europe et au-delà », Multitudes 2007/1 (no 28).

Holmes, Brian, 2007b, « L’extra-disciplinaire. Pour une nouvelle critique institutionnelle », revue Multitudes n°28.

Ivekovic, Rada, 2012, « Conditions d’une dénationalisation et décolonisation des savoirs », Mouvements n° 72, p. 35-41.

Mezzadra, Sandro et Neilson, Brett, 2012, « Fabrica mundi : Dessiner des frontières et produire le monde », in Kantuta Quirós et Aliocha Imhoff (dir.), Geo-Esthétique – le peuple qui manque), coéd. Parc Saint Léger et École Supérieure d’Art de Clermont Métropole.

Mezzadra, Sandro et Neilson, Brett, 2013, Border as Method, or, the Multiplication of Labor, Durham, Duke University Press.

Mignolo, Walter, 2015, La Désobéissance épistémique : Rhétorique de la modernité, logique de la colonialité et grammaire de la décolonialité, Berne, Peter Lang, « Critique sociale et pensée juridique ».

Mogel, Lize et Bhagat, Alexis, 2008, « Mapping Ghosts », Visible collective talks to Trevor Paglen, in Lize Mogel et Alexis Bhagat, An Atlas of Radical Geography, Los Angeles, Journal of Aesthetics and Protest Press.

Paglen, Trevo, 2008, « Experimental Geography: From Cultural Production to the Production of Space », in catalogue d’exposition Experimental Geography. Radical Approaches to Landscape, Cartography and Urbanism, NY, Nato Thompson and Independent Curators International, Melvillehouse.

Quirós, Kantuta et Imhoff, Aliocha, 2012, « Glissements de terrain », in Kantuta Quirós et Aliocha Imhoff (dir.), Geo-Esthétique – le peuple qui manque), coéd. Parc Saint Léger et École Supérieure d’Art de Clermont Métropole.

Tiberghien, Gilles, 2007, Finis terrae. Imaginaires et imaginations cartographiques, Paris, Bayard, « Le rayon des curiosités ».

Notes...

Notes

13

1. In the introductory text entitled “Landslides” (Glissements de terrain) to their work Géo-Esthétique, Kantuta Quirós and Aliocha Imhoff share the importance of these changes in what the art theorist Joaquín Barriendos calls “geo-aesthetics”, which has established itself as a criticism of new internationalism by showing that “if it has taken on the trappings of ecumenism exhilarating global art, which now includes artists from the famous ‘emerging regions of geo-aesthetics’, the product of this new tale often continues to be articulated and formulated from within the economic, geopolitical, institutional and discursive centres of power.”

2. One example of many.

3. We refer here to the seminal work by Paul Feyerabend (1979): “Passionate and provocative, this plea for a more libertarian approach to knowledge gathering and against all kinds of methodological straitjackets is rooted in a meticulous analysis of the shows of strength that have shaped the development of science. Laying bare the tricks of modern epistemology, Feyerabend vehemently and playfully renews the debate around reason” (excerpt from the back cover).

4. One example is the artist residence offered by the ARTifariti collective, which asks artists to produce a work at the foot of the “wall of sand”, the wall stretching 2,700 km. that the Moroccan government erected in Western Sahara to assert its sovereignty over this former Spanish colony despite the Front Polisario’s claims of independence (http://www.artifariti.org).

5. For example, the programme entitled The end of maps? Dreamt territories, normalised territories that the Pantheon-Sorbonne University offers, the Border Aesthetics programme at the Arctic University of Norway, the European Union–financed Euroborderscapes project, the Arte fronterizo programme of the University of Mexico and, of course, the AntiAntlas of Borders.

6. In this regard, see issue no 28 of the journal Multitudes for more on the Transform project of the European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies. This project seeks to explore the conditions for and possibility of a third phase of institutional criticism for which Brian Holmes, among many others, proposes the notion of extradisciplinarity.

7. See www.nettime.org

8. See his series of photographs, Untitled (Drones) http://www.paglen.com/?l=work&s=drones

9. See http://dronestagram.tumblr.com

10. Voir his film The Freestone Drone, 2013.

http://waterside-contemporary.com/artists/george-barber

11. A modern-age pirate working in technological security, Samy Kamkar has developed the software Skyjack that detects drones and takes control of them.

12. Adam Harvey is an artist and designer whose clothing line, Stealth Wear, consists of camouflage outfits made from material that is invisible to drones’ heat-sensitive infrared sensors. http://ahprojects.com/projects/stealth-wear

13. See http://dronestagram.tumblr.com

14. For more on this topic, see the article by Rada Iveković (2012).

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/01-Guillo-border-art-and-borders-of-art.pdf