antiAtlas Journal #3 - 2019

Fragile borders in Sub-Saharan Africa: the nexus between economy and insecurity at borders

Thomas Cantens

In Sub-Sahara Africa, armed groups who have politico-religious projects favor borderlands to create and govern new territories. The article aims to analyze the different strategies followed by these groups and the State’s responses, based on fieldwork missions conducted in fragile borderlands. It also discusses the role of “technology as a common language on techniques for State agencies, and the potential contribution of geospatial technologies for this purpose.

Thomas Cantens has been the head of the Research Unit at the World Customs Organization. He is a French Customs officer and associate lecturer at the University of Auvergne (France). He worked in several African countries, has a title of engineer and a doctorate in social and political anthropology. He has published on borders, corruption, informal trade, the use of technology and numbers, and security. He is now in position in Niger. Email: thomascantens@hotmail.com

Keywords: Africa, Sahel, insecurity, armed groups, border economy, geodata

The author thanks the organizers and the participants of the 2019 Shield Africa Conference (22-24 January 2019, Abidjan, Ivory Coast) and particularly Mr. Michel Foucher, scientific director of the conference, to whom this paper has been presented. The author also thanks the Secretary General of the World Customs Organization, Mrs Monika Weber (International Center for Migration Policy Development), Mr. Gael Raballand and Mr. Geoff Handley (World Bank), Mr. Mourad Arfaoui (World Customs Organization) and the heads of Customs adminstrations of and Customs officers from Nigeria, Niger, Sudan, Libya, Tunisia, Somalia, Central African Republic, Burkina Faso and Chad for having made the field missions possible.

Photograph © Thomas Cantens, Lac Tchad, 2016

To quote this article: Cantens, Thomas "Fragile borders in subsaharian Africa: the nexus between economy and insecurity at borders", published on December 4th, 2019, antiAtlas Journal #3 | 2019, online, URL : https://www.antiatlas-journal.net/03-fragile-borders-in-subsaharian-africa, last consultation on Date

Introduction

1 Many African nations are struck or threatened by security crises due to the presence of armed groups seeking to drive out and replace the government in certain parts of the national territory. In Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Somalia, Libya and Central African Republic, "insurgent", "rebel", "terrorist" groups endeavour to settle in border areas in particular, to take advantage of the border economy and the difficulties neighbouring countries' security services have in coordinating their surveillance. Contrary to what certain analysts predict, most of these groups face difficulties to "globalize" their uprising and remain in the border area where they first formed or have moved to.

These crises are often thought to have their roots in the governments' failure to effectively support local development, outside the main urban centres. The response of governments is a security-development nexus consisting of, on the one hand, strengthening the security apparatus with more extensive resources, state-of-emergency measures and sometimes foreign military support and, on the other, assisting the local people in traditional development sectors such as education, health and farming.

Papers have already been written on various aspects of these crises including their effects on agriculture (Van Den Hoek, 2017) or the economy in general, the spatial analysis of their factors (Raleigh 2010, Schutte 2011, Adem 2012, Hadley 2018), the environmental factors (Ayana 2016), the reasons for joining armed groups (Théroux-Benoni et al. 2016), customs practices (Cantens and Raballand 2017), and the connection between insecurity and development (OECD DAC 2003, Cantens 2018).

next...

2 This paper completes these works by focusing on the role the border economy plays in the crisis, after sixteen missions carried out between 2016 and 2018 at land borders marked by insecurity: (i) interviews with various local and national players, security and defence force representatives, intelligence service representatives, economic actors and sometimes "traditional chiefs and religious leaders" as well as armed group militant prisoners; (ii) travels to the areas of insecurity with customs officers often accompanied by security forces; and (iii) quantitative analyses of geo-located data on violent incidents and, in some cases, customs and trade data.

This paper aims to introduce the importance of cross-border trade and the challenges of its regulation, such as the circulation of wealth, into security and development policies. In other words, it aims to encourage security policies to take greater account of the border economy, in order to safeguard its forms or even to use it as political leverage against insurgencies.

next...

3 Three preliminary remarks clarify the angle taken in this paper. Firstly, the armed groups in question are not driven by the aim of wreaking chaos. They are organised and often led by educated individuals who have knowledge of the international context; they seek to establish order in a delimited area, even if we regard their actions as incensed. The same groups may, by applying similar strategies (suicide attacks for example), want to create chaos in Western countries and establish order in other nations. In these other countries, the groups follow a logic of insurgency and may adopt terrorism as their strategy. This paper shows how managing the border economy is part of this order and how it is in competition between governments and armed groups.

Secondly, order does exist in these border areas. National boundaries are still meaningful, despite their "porosity" and the "informality" which is often said to "challenge" them. This paper defends the idea that borders are only porous from a governmental viewpoint. This so frequently mentioned "porosity" reflects a standard ideal of borders, which does not exist. Unless walls are erected or the area is turned into a lifeless military zone, border porosity is a normal characteristic to which we must adapt.

Thirdly, the paper seeks to report on the local dimension of the violence. By physically travelling out in the field, it is striking to see how one gradually enters the area of insecurity, whereas only a few miles away, everyday life peacefully goes on. The local dimension of the crises is not an isolated feature; it is part of the nature of the violence and conflict. This aspect must be firmly brought home because, when it comes to thinking about the solutions, it conflicts with the national perspective that government apparatuses take.

The first section provides a description of relationships between governments, armed groups and border economy. The second and third sections propose an analysis of security policies before suggesting some leads for reflection in a final section.

This paper does not purport to describe the singularities of the armed groups or to examine the question of insecurity in its entirety, if ever that were possible. It provides a point of view, that of taxation and trade, considering that some of the solutions to today's security crises can no doubt be found by reconciling military, police and economic perspectives.

next...

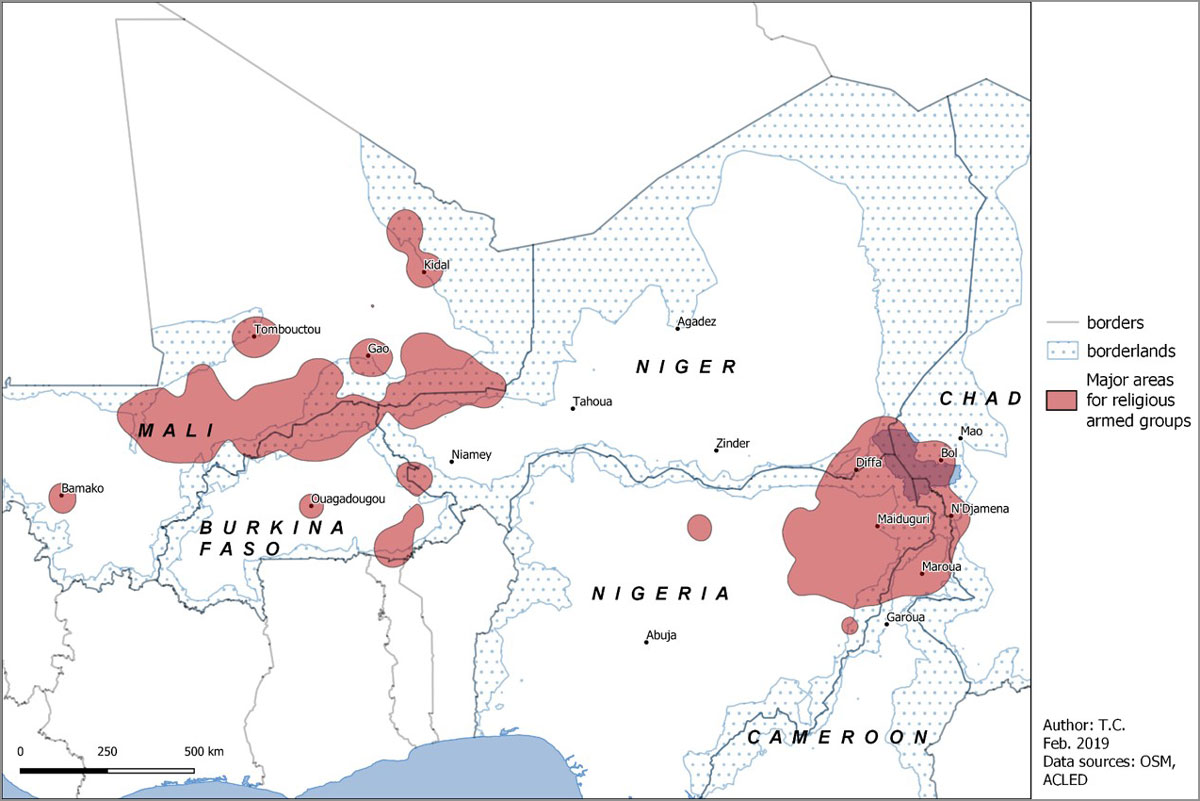

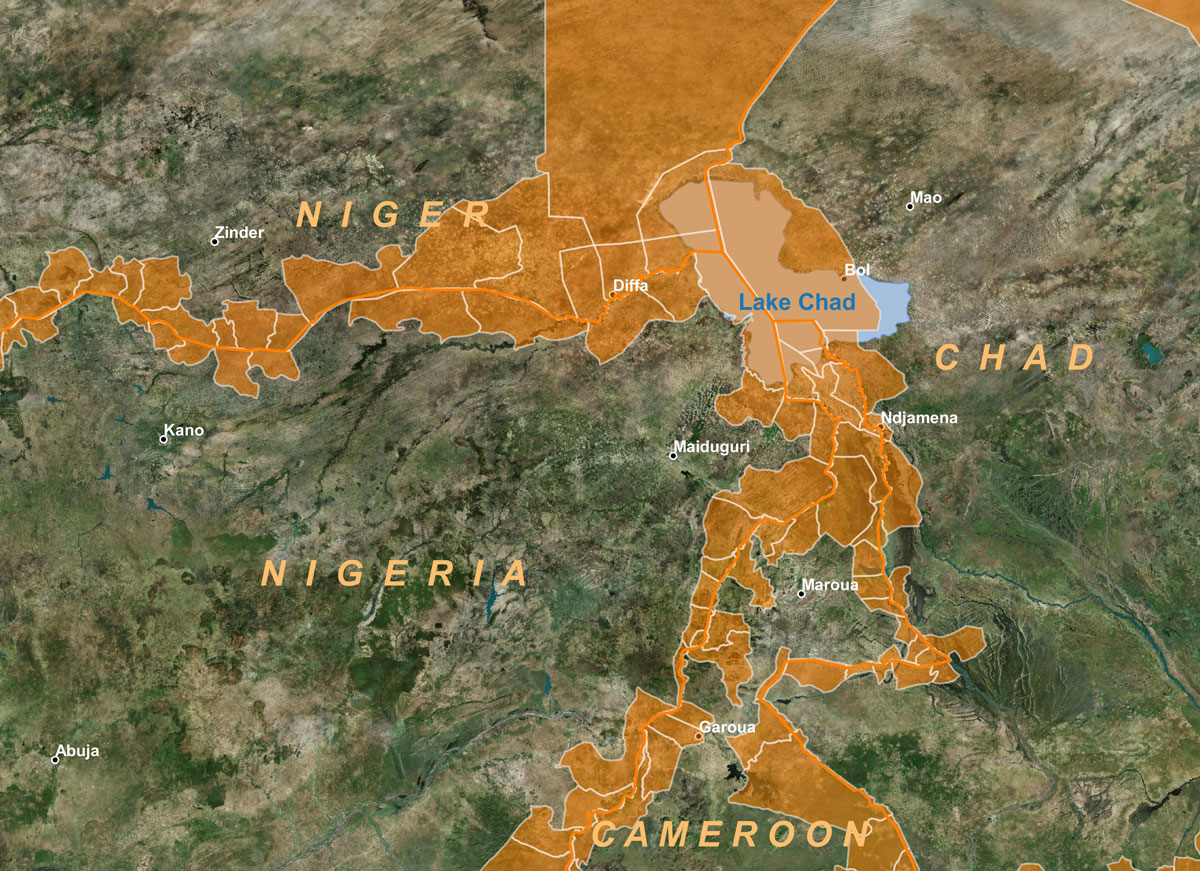

Map 1 opposite: distribution of religious armed groups in the Sahel (data source: ACLED)

I. Taxation and trade at borders in crisis situations

4Security crises have a strong political dimension fuelled by constantly deteriorating relationships between the local population and the government. Most armed groups base their action on religious views to transform society, unlike rebellions which seek to overturn and replace those in power without necessarily changing the form of governance. Religious armed groups want to set up different forms of governance to those specific to the colonial period - contemporary globalisation continuum. Although their strategy is transnational in scope, it consists in setting themselves up locally and gradually reconstructing a territory ("caliphates", "al-Dawla") in which they apply their rules.

This strategy has two consequences: the fact that practically all armed groups choose to settle in border areas, and the fiscal competition it creates between these groups and the government in respect of cross-border trade.

next...

Armed groups on the economic and geographical margins of the national territory

5 Our research based on ACLED datashows that in the Sahel, border areas represent 30% of the territories but are the scene of more than 47% of the fatalities. All the armed groups in the Sahel operate at borders, except for Mali which is now seeing groups operating in the middle of the country (but not far from the border with Burkina Faso). More than 60% of the religious armed groups happen in borderlands.

These areas are technically propitious to their development: they can harass isolated security forces in rural areas, use the border as an obstacle to pursuits due to the complexity of coordinating security forces, and sometimes attempt to stifle the economy of hostile towns by cutting off trade routes. This appears to be the case of Maiduguri (Nigeria) where, in June 2018, Boko Haram groups switched from a strategy of levies on trucks travelling between Nigeria and Cameroon to destroying them.

Secondly, it is difficult for an armed group to buy supplies on a market or to sell goods or farm produce seized in villages. On markets, including the biggest ones like Maiduguri, the economic players all know each other and the arrival of new buyers or vendors arouses suspicion. The armed groups therefore use intermediaries, probably border people who are used to liaising between markets on either side of the borders. The search for this local support also partakes of a form of governance and development. Similarly, an inhabitant of Timbuktu (Mali) reported that people from Timbuktu had done some good deals selling their goods at very high prices to members of AQIM and Ansar Dine in 2012. The buyers were doubtless not naive and saw their very high-priced purchase of the Tabaski sheep as an opportunity to build bridges with the local people while at the same time injecting money into the local economy.

next...

6 Lastly, the border is an economic and symbolic resource for populations whose lives are historically connected with contraband and avoiding the government. Businesses specific to the border economy, such as trade, transport and brokerage, are among the most liberal and liberating of activities accessible to "cadets sociaux", i.e. youths, members of little-represented linguistic groups or populations at the bottom of the traditional scales: it takes only a small amount of money to start up a business, without the need, as is the case with farming, to obtain the family or village's social permission to gain access to land.

In Niger, in the Diffa region, poor rural people hit by the crisis join together to start up small business activities ("convoy trucks"), whereas in the Maiduguri region, Boko Haram has used support for trade as political leverage by financing shall businesses. In northern Mali, merchants from Timbuktu were suspected of being dependent on the armed groups which had granted them credits.

Trade is also a source of practical knowledge about movement that can be valuable to the armed groups: in the Sahel, these groups use motorbikes which are faster on the bush tracks than 4WD vehicles and their drivers are "stuntmen" (Seignobos 2014), a named used by customs officers for the youths who used to be involved in smuggling on motorbikes before the crisis began.

next...

7 The armed groups therefore rely on the border, for purely technical reasons (it is easier to avoid surveillance by security services, to sell and buy goods, and to recruit young people who have practical knowledge) but also for political reasons, as they use the border economy as a source of opportunities for the "cadets sociaux". The border economy therefore represents, as described below, a tax resource whose governance is a political battle between armed groups and governments.

next...

Northern border area, illegal fuel station - photograph © Thomas Cantens

Religious armed groups and the governance issue of the circulation of wealth

8 In border areas, armed groups may set up a tax system in the general sense, for example a direct levy on political figures or merchants, or tolls on trade routes.

In Borno State (Nigeria), at the boundaries with Cameroon and Chad, the Boko Haram groups have especially targeted big merchants from Maiduguri by kidnapping for ransom their relatives who work as intermediaries at the border crossings with Cameroon. In rural parts, when the insurgencies remain uncertain, armed groups harass customs and police officers to force them to withdraw to the large urban centres; they do not prevent the cross-border flow of goods but, in a way, they facilitate it through the smuggling induced by the absence of any territorial control, apart from the occasional military presence.

next...

9 By raising funds, on trade or capital, armed groups do not just meet their basic needs that they could satisfy simply by stealing. They also demonstrate their ability to govern and to organise the area by imposing a fiscal order which is not necessarily so different to the state order. Taxation thus becomes a battle field between the government and the armed groups: the contribution paid by elites to armed groups represents a loss for the government, and it is easier to negotiate with the public services than with armed groups. Furthermore, tax on trade, whether imposed by the government or armed groups, has inequalities and inefficiencies which make it a policy tool for organising the circulation of wealth across the territory.

In the case of tolls, the armed groups set themselves up in places where the government was once present, namely at border posts. At the border between Tunisia and Libya, at Ras Ajdir, "the first ones to get up in the morning take the border". On the Libyan side, the former local militias are hired into the national customs administration.

Sometimes, the armed groups set up on the roadblocks once manned by the state forces they have chased out: by replacing the government, these "historical" barricades given them significant symbolic strength, but they also take advantage of the hands-on knowledge of informal taxation practices which the "petits" can provide, i.e. those youths who used to do small repetitive and demanding jobs for police and customs officers, such as lifting barriers, clearing cans from the road and sometimes collecting small payments to facilitate the crossing.

In Somalia, the al-Shabaab group applies different taxes to merchants working in Kismayo (Jubaland State) depending on whether they come from Jubaland or Mogadishu. And the merchants attempt to negotiate a tax with the authorities that takes into account the levies they pay to the Shabaab. The explanation put forward by the local government is that half of their budget is spent on security measures to counter the Shabaab. In the north of the Central African Republic, armed groups also apply different taxation based on the religion of cross-border merchants. In Cameroon and Chad, when the two main throughways between Nigeria and Chad were cut off, the merchants crossed the desert between Niger and Chad, and some admit that, while they faced bigger risks in terms of bandits and armed groups by crossing the desert, they avoided the many security and customs roadblocks and the taxes and payments collected at them. The levies that armed groups collect on trade shape and alter trade routes and contribute to reorganising the social group of merchants.

next...

Lake Chad, border area 2017 - photograph © Thomas Cantens

10 Conversely, in northern Burkina Faso and in the Diffa region (Niger), the armed groups apparently do not try to apply parallel taxes but cross-border trade is still a governance issue.

According to discussions held with the merchants, these groups do not force them to pay any financial contribution directly connected to the goods, but they use State taxation as an ideological foil. In this area, one group waited for their trucks to pass the gendarmerie post before they attacked it, and then the members told the drivers that they had waited for them to pass through before launching the attack to avoid harming them. When drivers and merchants are intercepted by the armed groups, their mobile phones are searched in order to delete any "shocking" pictures and install religious ring tones, then they are given a brief sermon about their activities, such as rules to be applied when men and women travel together for example.

The example of Amadou Koufa taking the town of Konna in Mali in 2013 and declaring the end of taxation, as well as the recurrent abolition of tax in towns taken by the Jihadists are characteristic of the semantic shift the religious groups want to bring about: from tax as a forced contribution to a distant state apparatus inherited from a western model, to a voluntary contribution based on religious values.

next...

Lake Chad, 2017, patrolling the border area - photograph © Thomas Cantens

II. Government responses: controlling movement and cooperating

11 Two watchwords guide security policies: controlling movement and cooperation.

Reducing movement

12 Controlling movement in fact means reducing movement by banning the use of certain means of transport (motorcycles, 4WD vehicles and pick-ups), certain routes (on Lake Chad in particular), and creating keep-out zones in which the armed forces consider any presence hostile.

However, historically, these areas are linked to movement, both local and more distant (trans-Saharan). Symbolically, these policies are seen as major obstacles by populations already distrustful of the government. This distrust is heightened when merchants and carriers are victims of certain security staff who use state-of-emergency measures (identity checks, physical inspections of goods) to extort small sums of money from them and depart from the mandatory controls.

Secondly, these policies rarely distinguish between different types of trade, i.e. between informal trade of basic necessities and a weapons smuggler, insofar as they use similar vehicles and routes (Cantens and Raballand 2016).

Lastly, controlling movement costs the controlees money due to unloading at borders, waiting time, storage and guarding costs, theft during storing, and new routes with new means of transport2. For instance, when Lake Chad was closed to navigation in 2016 along with the Maiduguri (Nigeria) - Gamboru (Nigeria) - Kousseri (Cameroon) – N’Djamena (Chad) route, merchants had to charter trucks and cross the land border between Niger and Chad. But the crossing was much more costly and complex: the canoes that crossed Lake Chad could carry the equivalent of three truckloads. Insecurity sometimes comes at a higher price (killings, theft or burning of cargo and means of transport), but not always, and the economic players view security policies with this uncertainty, especially when they fail to completely secure the territory.

next...

Chad-Sudan border (West Darfur) cross-border meeting between State services

photograph © Thomas Cantens 2016

Cooperation

13 The second watchword is cooperation, but it is difficult to organise and institutionalise, particularly between the military, the police and customs. On a local level, where the authorities organise regular meetings on security, information is shared, even though the civil services are seldom called upon, despite having special relationships with the local people. Joint patrols are still few and far between. At national level, cooperation between civil services (customs) and intelligence agencies is almost inexistent, apart from the occasional nascent exception. The "intelligence community" is still quite limited to traditional participants and closed to civil stakeholders.

There are at least four reasons for this low cooperation, particularly between the army and customs, i.e. the two main players in these areas.

The first reason is cultural. Traditionally, the role of customs and tax authorities has been confined to collecting revenue. Today, this is no longer possible, but few customs authorities have developed a new doctrine. In its absence, the civil authorities are often "dragged in" by the military apparatus responsible for controlling the zone. In some places, customs officers are used as back-up troops for the army when they recapture villages from armed groups or for night patrols in urban areas. Senior customs officers complain that they play a military security role to the detriment of their role in taxation and controlling goods. Elsewhere, customs officers are against joint patrols, fearing they will be seen as excessively repressive forces and will no longer receive help or information from the local population since military operations are mostly led to take villagers in for questioning on the strength of denunciations.

The second reason is the lack of expertise of civil or paramilitary players such as customs and particularly the fact that they do not share a common language with the armed forces and intelligence agencies. This can mean that they do not share any common communication channels on the ground but also any common vocabulary. Customs authorities do not have the technology they need to work with the armed forces which use resources that customs officers have not been trained or are not equipped to use, such as convoys or geographical and satellite data. One senior customs officer explained how using satellite imaging and military-geographic jargon such as "Area of Interest" or "Situational Picture" had facilitated his communication with an intelligence agency and, no doubt, the signing of their partnership.

The third reason is that cooperation can cost the public administrations money. It costs money for customs officers and soldiers to patrol together at the request of customs and they must sometimes fund the military units who accompany them. Cooperation decided at national and international level often impacts the internal budgets of public administrations locally.

Lastly, the problem of trust cannot be overlooked, on both sides: corruption, which is found in all the services, is detrimental to the entire process. "When everyone must be informed to organise an operation, it is seldom successful", complained a customs officer when asked about his cooperation with the security services in order to follow up information from an informant and go out into the field. The armed forces no doubt mistrust the tax and customs administrations in the same way.

suite...

Basic equipment - photo © Thomas Cantens, 2017

Central African Republic 2017, one morning at a border camp - photo © Thomas Cantens, 2017

III. Computational bias in fiscal contracts

14Computation – in the quantitative sense of ordinal and cardinal properties of figures – is a policy practice that deserves greater attention (Cantens 2018b). Beyond the technical difficulties, government solutions involve a policy difficulty when analysed from the angle of circulation of wealth or when examining the meaning of the calculations they make.

Fiscal containment

The first policy logic in fragile border areas is containment: contain movement, violence and informal trade within the fragile area and avoid this informal trade overflowing into centres supplied by formal flows transiting via non-fragile zones. The system – which was adopted before the crises and is still partially in force in some areas – consists in allowing fiscal pressure on cross-border trade to be negotiated locally, below the taxation applied at borders crossed by major trade flows. The argument is twofold: in light of the insecurity and the environment, it is better for merchants to come and declare of their own free will than get involved in uncontrollable smuggling; secondly, the local people are particularly poor and they may not be subjected to the same fiscal pressure.

The technical counterpart to this fiscal "facility" is a redefinition of a new fiscal limit within the country, isolating the favoured border area from the rest of the territory and materialised by customs barriers: goods entering the favoured border area must not leave it or else they will be taxed again when transported to the rest of the territory. This internal "customs duty" is sometimes applied informally by customs officers themselves, but it is sometimes more or less formalised with the administration which wants to control it. Tolerating informal trade, isolating the "poor" border area and protecting the "richer" trade centres from contamination by informal trade are the three factors of the economic containment policy often adopted in fragile areas.

next...

15 These strategies can be useful in the short term but, in all cases, they reveal and proceed from a computational bias.

Governments spend significant amounts on "profitable" borders which generate customs and fiscal revenues. There are usually two or three crossing points in total for a whole country: a port, and one or two land points for landlocked countries. Donors and international organisations provide assistance and technical and financial incentives to encourage governments to apply international standards at these points. As a result, fiscal pressure at these points is relatively good (and high) and they benefit from significant human and material resources, with constant reform and modernisation projects. In parallel, this situation fuels the "advantageous" nature of poor borders.

The problem lies in the computational scale.

Statesmen, i.e. governors, senior officials and international experts – do a national calculation, but locally, at the "poor" borders, the wealth that circulates is, in relative terms, substantial. This is the lesson learnt from the Malian case: an area where the authorities thought they could fiscally contain political claims became a zone of national interest at the origin of the central government's quasi-fall.

next...

Security-based fiscal contract

16 The second policy logic in situations of insecurity is to offer a fiscal contract based on security: "pay taxes and we will be able to ensure your safety". But it disregards two key factors: time and trust.

Time is important. In areas where state presence is no longer satisfactory, the population adopts short-term, informal security solutions (militia or local groups of youths) which cost less, for the economic elite, than paying tax to the government. This solution is sometimes also encouraged by certain governments which prefer to leave armed action in the hands of civilian groups more familiar with the intervention ground (bush, forest, desert, etc.). Self-security and security in general are governed by different temporalities. The merchants questioned fully understand what government tax is and how, in theory, it allows the government to fulfil its sovereign duties. But their problem is their own security right now. In Mogadishu, one importer compared the more than a million US dollars he paid each year in customs duties and taxes to the 50 US dollars he paid each month to some local youths to ensure his safety. He rolled out a calculation of all the basic government expenditures, revealing extensive knowledge of a federal budget. Elsewhere, the people form alliances with armed groups who can defend them. In Gao, the population has sought assistance from the Islamic police of Ansar Dine and MUJAO to rid the town of members of MNLA, a non-religious group allied with the former, which engaged in pillage.

Mistrust is the second factor that invalidates the government's fiscal contract strategy.

Everywhere, people have very little trust in security apparatuses. Due to the corruption and sometimes violence of some security force members, people regard the state as one armed group among others. There is no ideological barrier: nowhere did any elite merchants complain of the armed groups' ideology. The population is often neutral towards what it regards as a conflict between the government and religious armed groups.

Mistrust in the government is nothing new. What is new is the emergence of new players, the religious armed groups, who negotiate nothing (at least not politically) and offer a different governance model, putting an end to all forms of corruption, from "corruption of morals" to the corruption of government employees. These groups differ from "organised crime" which needs the state and particularly corrupt state services to derive profit from their unlawful activities.

next...

17 It would be difficult to say that armed groups are good tax collectors and set up a "better" tax system than governments but, at this stage, the different findings have shown that they achieve four goals which governments often do not: (i) they assess the wealth of elite groups and often "tax" them with the help of local informants; (ii) they are coercive, as no negotiation is possible and the death threat is dissuasive; (iii) there is little or no corruption in their bureaucracy (in Somalia, the Shabaab give drivers tax receipts to avoid them being taxed at subsequent roadblocks, and the receipts are collected at the last roadblock and sent to a controller who reconciles the accounts), (iv) they propose an ideological rather than technical legitimisation of taxes, based on religious values and language.

Thus, in places where these groups establish a form of taxation, it develops, either freely or by force, a link with tax – and thus between the population and its governors – which is more political than the one built by a "technical developer" government, a model often found in so-called developing countries and encouraged by donors.

next...

Northern border of Burkina Faso 2017, an advanced post

IV. A few topics for reflection

18In the end, the fact that insecurity is not caused by a conflict between states, and that borders are "porous", "transgressed" (Grégoire 2018) or challenged (Assouga 2018), does not mean that borders are inexistent. Giblin (2018) notes in general that in modern-day conflicts, borders are not necessarily challenged as regard their limits, but they are at stake in the fight for their possession. In our situation, borders are indeed at the centre of the crises caused by religious armed groups, both geographically and economically.

next...

"Fragile border": recognising the geographic specificity of the crises

19 It is important to recognise the specificity of security and development interventions in border areas because developers, NGOs, the armed forces and the police should not intervene in a border area like they do in the rest of the country.

If we have developed the terms "fragile borders" (Cantens and Raballand 2016) through our research, we have done so for two reasons which, while they might seem conceptual and sometimes anecdotal compared to the challenges on the ground, could help to better describe the situations.

On the one hand, referring to "fragile borders" draws a distinction with the notion of "fragile state", ill-suited in many regards. Firstly, a state may not be "fragile" within the meaning of international rankings and may need to manage insecurity in some border areas. This is the case of numerous African nations mentioned in this paper. Secondly, using "fragile state" perpetuates the clerical error mentioned above which is clear to see from experience in the field: the violence is very local, as is the wealth, and this local dimension must be understood at government level and not included in national calculations on a territorial scale. Conflict and war are reduced to their most concrete form: that of violence perpetrated somewhere, a state of insecurity marked by conflicts between governance methods seeking to create order inside a delimited space.

On the other hand, the interviews held on the ground show that there is no shared language between civil and military forces, even though they are active in the same space, between the military "front" and the customs "containment zone". National or regional security units could therefore:

- Recognise the border specificity of the security problems and the need for security interventions that integrate the importance of the border economy and plan security measures with regard for the positive and negative impacts on this economy;

- Ensure a civil government presence in a crisis zone irrespective of the tax contribution it makes to the national budget;

- Propose solutions to security issues that include taxation as a policy tool of social justice, thereby meeting the need to restore the people's trust in government, beyond mere budgeting.

next...

Stop thinking that "resilience" will suffice

20 The social structures that rely on the border economy change both during and after these crises. Merchant groups are highly structured in these areas, probably more so than in the large trade centres such as ports.

A few "big merchants" have a quasi-monopoly over basic necessities like flour, oil and milk. "Medium-size merchants" or smaller players, sometimes in association, are active in other sectors such as clothing, shoes, biscuits and confectionary. They join forces to place orders, charter trucks and assemble their various goods in "convoys", just like cargo bulking in ports. These small or medium-sized merchants are obviously more vulnerable to security crises: they do not have the same financial base to weather the shocks; they do not always have correspondents in the ports with whom they have long-standing ties, passed down over the generations; and neither can they transfer their business from these areas to the coastal nations, like the big merchants are doing. In Bol (Chad), merchants work together to buy goods in Maiduguri (Nigeria), each one giving contacts, money and orders to a representative. Paradoxically, these merchants in small towns can cope with the crisis better, as they rely on solidarity by lending money or sharing contacts. In the large regional trade centre of Maiduguri, on the other hand, the number of cross-border merchants has declined and the medium-sized merchants have disappeared; to meet demand, the big merchants have had to expand their business by importing the goods the small merchants were specialised in. In Diffa, small merchants are facing competition from newcomers to the border economy, the villagers driven out of their lands by the insecurity or state-of-emergency measures.

Two remarks concerning security policies are thus called for. Firstly, the social structures before the crisis are relatively strong and, by the wealth it generates, cross-border trade contributes to them.

Secondly, the problem of restoring state authority arises both during and after the crisis: the situation after the height of a security crisis is not the same as at the beginning and the civil state, particularly fiscal, will find a different economic structure at the border, probably more concentrated around a few elite merchants who will have gained political influence. Therefore, the central government must not lose the support of these elite merchants – and in some parts, it must even earn that support. This opens up another lead, different to those in favour of securing support among the "intellectual elite" (traditional chiefs and religious leaders). These elites cannot be part of post-crisis solutions because, as "elites", they shoulder a part of the crisis responsibility at least for failing to prevent it and because its outbreak demonstrates their political inefficiency and the population's loss of trust in them (Cantens 2018).

next...

Strengthen the role of civil and fiscal administrations

21 The importance of borders suggests that customs should naturally be part of security schemes. Formally, this is more or less the case depending on the country, but it should be reinforced, by better preparing senior customs officers, developing a clear doctrine for action integrated into security and fiscal policies, in complement to the action of security and defence forces. Customs authorities can provide this economic link between security and development, because they are at the interface between the two components.

Customs have a good understanding of the economic fabric and all its stakeholders. They have a high capacity to contribute to intelligence, reinforced by the fact that customs collect data via their customs clearance information systems which have been in place throughout Africa since the late 1980s. These data are useful for the economic evaluation of the crisis and the security responses, but they can also be harnessed to detect anomalies in trade flows, to track sensitive goods (motorbikes, fertiliser, fish and cattle) or to analyse changes in the organisation of economic actors.

As paramilitary forces, customs also operate outside urban areas, which places them at the interface between security and economy and means they can assess the positive and negative impacts of security measures. Governments need this perspective. In places where security constraints become too high for cross-border trade, the risk of smuggling rises. For instance, banning the flow of certain products used to make explosives is only effective if smugglers do not take over in this sector. In addition, "historical" smugglers are incited to turn to trafficking in high value-added goods, commensurate with the risks they take (weapons, drugs, etc.).

Finally, customs have quite a good relationship with the local residents, as they seldom use force and represent a solution for law-abiding economic players threatened by contraband and fraud.

The political relationship between customs and society is based on (i) a peaceful and regular relationship with the population, (ii) an economic role in facilitating cross-border trade and (iii) a fiscal role supposed to ensure fiscal justice and equal access to the border economy by fighting unlawful competition or monopoly situations. This "political" aspect of customs presence is important to fully restore the state in regions struck by insecurity.

next...

Inevitably deficient geographic cooperation

22 It may be necessary to abandon the cooperation ideal as it is currently pursued. In the absence of any truly effective cooperation, it results in all the participants submitting to one of them. This is due to reasons that are no doubt inherent to the type of participants and the situations. In other words, there is hope to improve it but, in all likelihood, the cooperation aimed for will never be achieved.

Cooperation may mean sharing information, even if some players must naturally share less than others: in principle, there is no limit on what a customs officer can share with intelligence services, but the opposite it not true. However, cooperation should not lead to one point of view or analysis monopolising all others. Each service, whether army, police or customs, must produce its own analysis for the political authority, and the authority must have the means to consolidate the different analyses. This consolidation is seldom done at present, and in our opinion, the political meaning of state intervention in crisis areas is obfuscated.

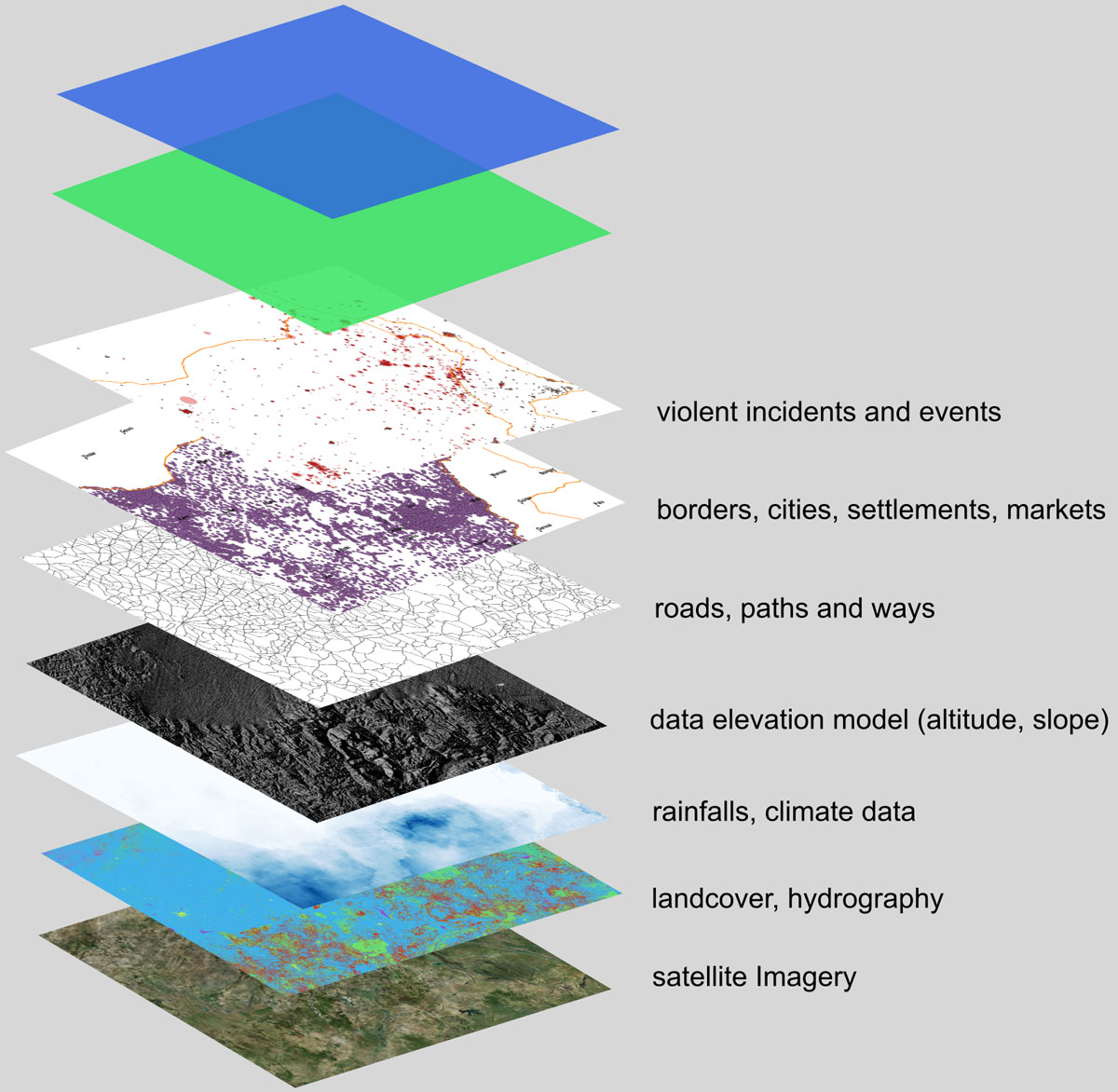

From a more technical standpoint, a common language - a technology, in the truest sense of technical language - must be adopted, and civil authorities must make an effort along these lines. As a civil authority, moving around the territory with defence forces and optimising the spatial deployment of their resources are important. Insecurity compels civil authorities, particularly customs, to modify their method of action: working in the field demands the deployment of more resources to ensure their own safety than during times of peace; optimizing the deployment of resources is therefore crucial. Customs officers have been analysing the risks ("who is most likely to commit fraud and who should be controlled?") for over twenty years. Today, this risk analysis must become spatial, by integrating geographical information. Furthermore, when combined with geographical information, customs data can simply be added to the cartographic data used by security forces to produce a complete image of the situation covering both the natural and economic aspects.

Finally, due to the type of information they contain, maps (or geospatial databases) are an instrument of cooperation per se, between highly different professions. We all share the space, but its representation, that of the border area, is different to a soldier, a police officer, a ranger or a customs officer. Maps are possibly the easiest way to strengthen cooperation at every level on the ground and centrally.

For the civil authorities, these methods must be developed locally, as no expertise can be found in countries which traditionally provide technical assistance. However, the forms these methods take are not unknown: training courses on the political and economic role of customs in security and in crisis areas, development of the intelligence function (databases, analysis training), and development of geographical information.

next...

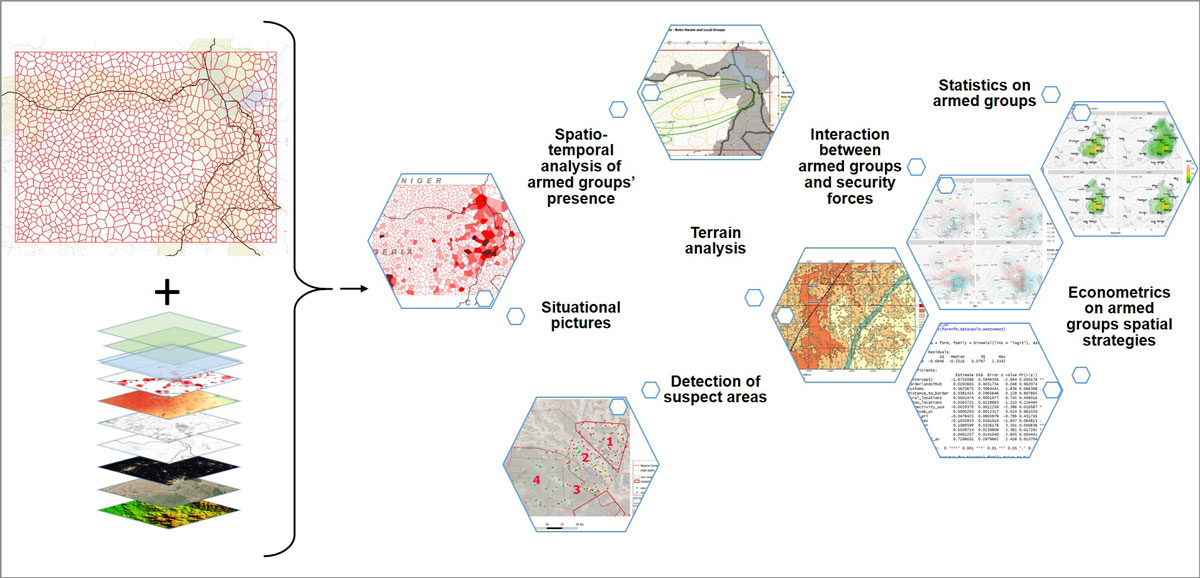

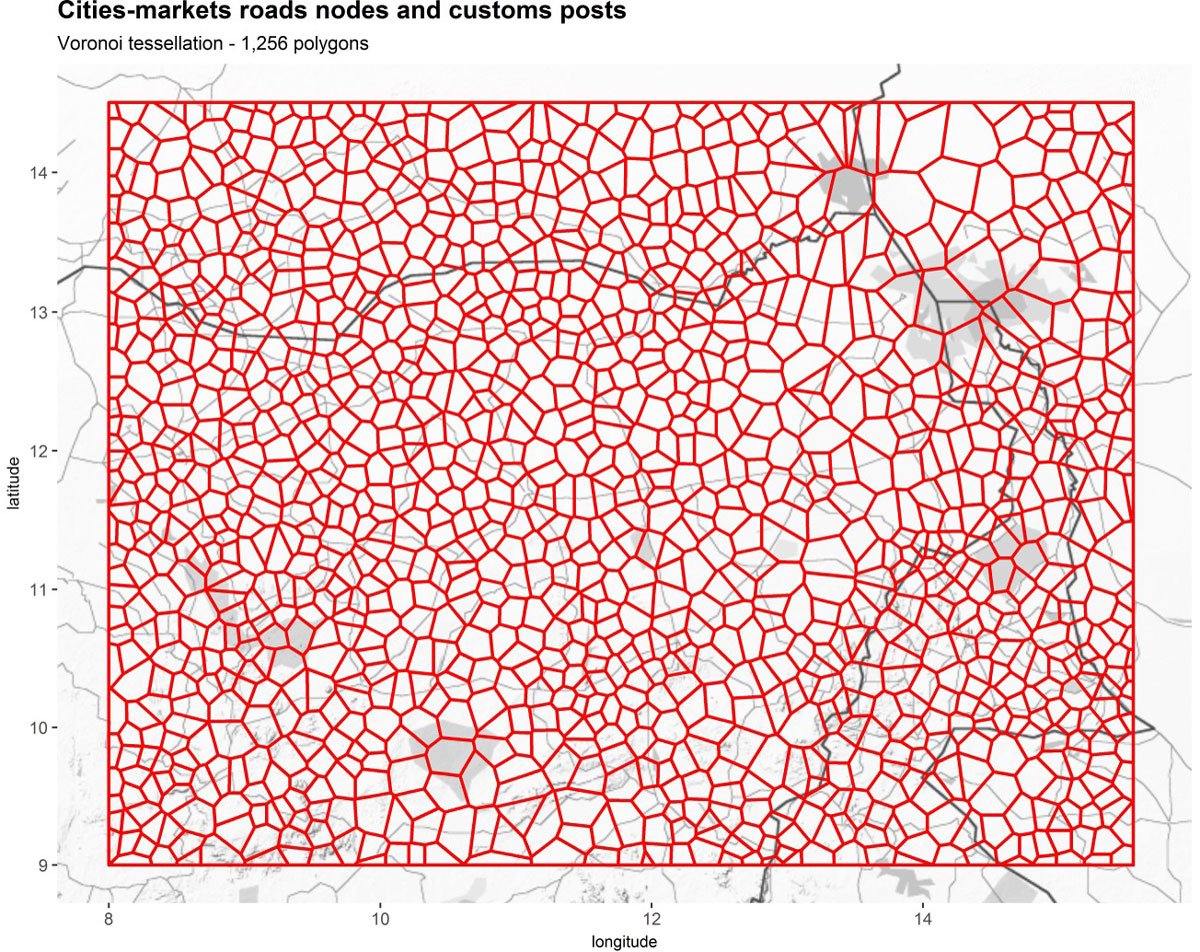

Figure 1 Organizing geographic information into data "layers".

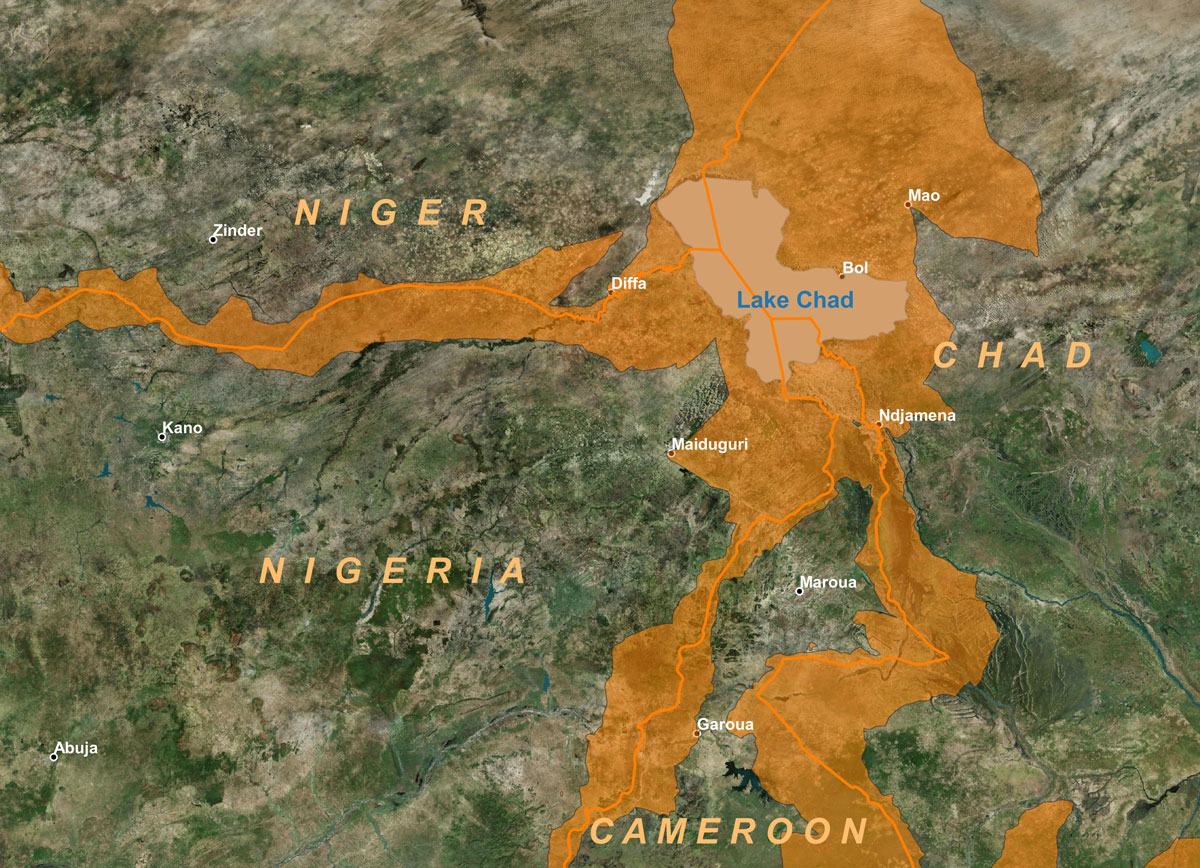

Figure 2: Example of an area of interest in the Lake Chad Basin (source: BING satellite imagery)

Figure 3: How to represent the border zone? First option: delimitation of the border zone along a fixed buffer zone of a few kilometres. This representation is not appropriate, as it does not take into account the "trafficability" of the terrain. From an economic point of view, the border zone is, for example, more extensive in the desert area than in the mountainous area.

Figure 4: How to represent the boundary? Second option: delimitation of the border area according to the administrative entities (counties, prefectures) in contact with the border line. This representation is not suitable for the analysis of armed groups and smugglers who do not respect administrative boundaries.

Figure 5: How to represent the border zone The solution adopted to represent the border zone is the use of an algorithm that plots the envelope of cross-border trade centres and routes.

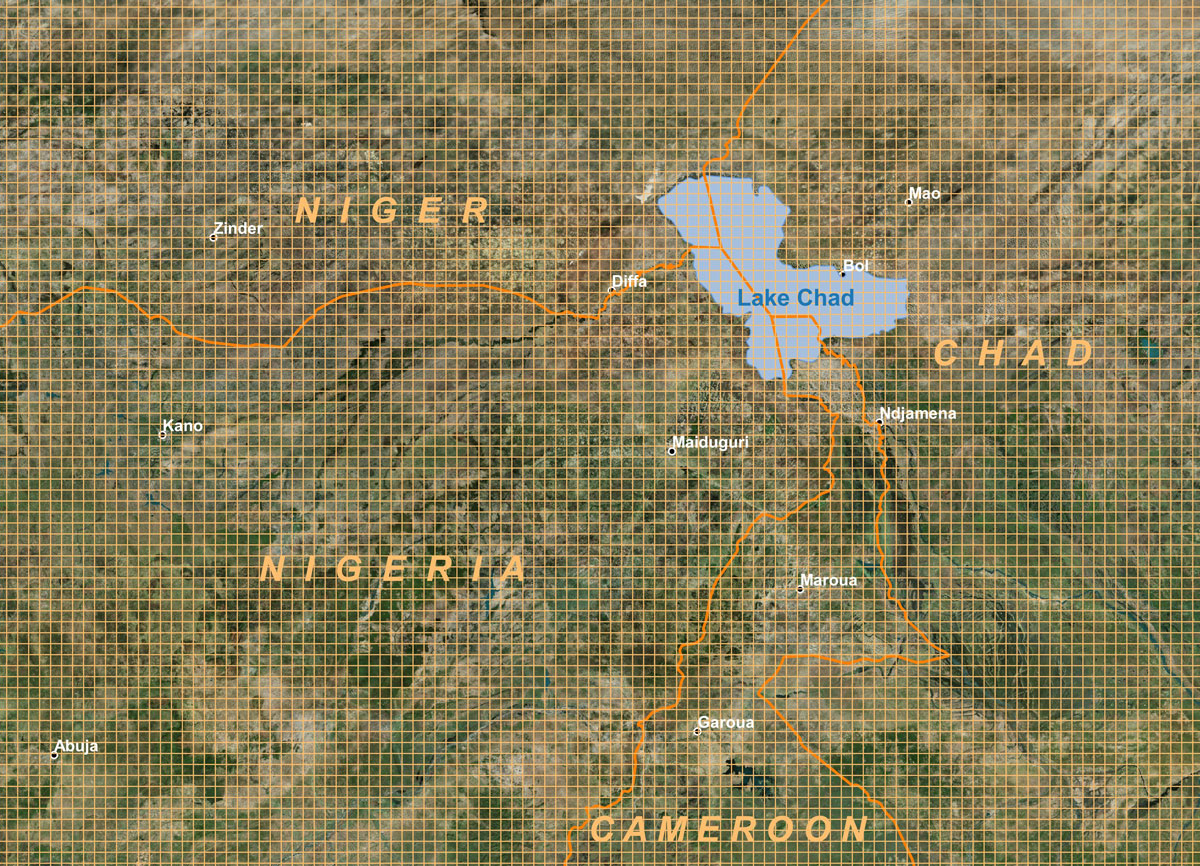

Figure 6. Which spatial model for the area of interest? First option: the "grid". This representation is often adopted to partition space. However, it is problematic if it is to be fine-grained and preserve the footprint of large localities. In addition, it does not take into account the road network.

Figure 7. Which spatial model for the area of interest? Second option: administrative division. This representation is often adopted, particularly in criminal studies, often because data are only available at this scale. As before, it is not appropriate since the movements of armed groups and smugglers do not follow an "administrative" logic and the transport network is not taken into account.

Figure 10 (above): Possible uses of geographic information.

V. Conclusion

23 Borders resist (Foucher, 2018), including for religious armed groups. In the "Salafistes" documentary by Ould Salem and Margolin (2016), the Islamist leader Omar Ould Hamaha interviewed in Timbuktu in 2012 said his sights were set primarily on Mali and that (at least initially) the neighbouring States would not be targeted. An armed group's short-term objective of taking power in a nation-state is not incompatible with a long-term goal of global expansion in partnership with other groups.

Security crises at borders call for a review of the distinction between the 'demarcation border', symbolising state authority, and the 'interaction border' which, according to Bigo (2011), results from populations in search of cultural and economic exchanges. The borders referred to above were and still are places of interaction. Even if these interactions have become military or more generally warlike, they have not left the economic or symbolic sphere; they involve aspects of violence, ideology and economics all at the same time, and state and non-state players sometimes regarded as equally legitimate by the population.

In the absence of government control, cross-border trade and its informality represent a triple opportunity for armed groups: (i) a source of low-cost supply, (ii) a source of tax on transport and goods, (iii) a political opening to attract those who are disadvantaged in the social organisation, by financing business activities to guarantee their social emancipation. Meanwhile, taxation partakes of the competition between armed groups and the government to establish forms of governance and to demonstrate to the people how the ruler's policy effectively organises the geographic and social circulation of wealth.

This pleads in favour of a more political than technical vision. It is unrealistic to say that a military, customs, police, economic or fiscal perspective alone can generate an adequate solution. Purely military solutions have never claimed to offer a political solution, they must solely create the right conditions for it (Charbonneau 2017). Moreover, defence force deployment requires major adaptations which may render it obsolete at a given time, as noted by Hanne (2017) when he reports on the new outbreak of terrorist action in Mali in 2016-2017.

In other words, the question is not just about knowing how to maintain or restore the state. It becomes: in which respects is the state actually more efficient and better than the other armed groups? This is not always easy for the local people to see. States are lacking a border policy compared to armed groups which have turned economic demands into policy issues while governments continue to treat them as technical problems. During a crisis, support for cross-border trade and the associated governance, taxation and control of smuggling could be meaningful avenues to explore for the security-development nexus. The challenge is both technical – i.e. collecting revenues – and political, i.e. demonstrating the ability to regulate the circulation of wealth in society and guarantee equal access to the opportunities the border economy offers.

The policy is local, just like the violence. Only a few miles from the war, there is no war. However, the aim is not to militarise borders. This critical fear of current border security policies is recurrent. And it is legitimate when cooperation is developed with the aim of unifying views of the situation rather than sharing information and securing mutual protection on the ground. Technology - intelligence, geospatial data and weapons – should be disconnected from the resulting use of force, or otherwise, technology should be disconnected from the realm from which it proceeds.

Populations make borders. If the border is not taken into account, there is no support for governments. And the border economy is not exclusively based on agriculture or cattle-breeding; far from it, it is based on movement. The people living at borders must stop “being in the grandstands", spectators of battles between the states and the armed groups, and being the first victims of this situation.

next...

Figure 8. Which spatial model for the area of interest? The chosen option is the use of a Voronoi diagram algorithm, a paving of space according to units of areas whose central points make sense for a representation of the border economy: for example, road nodes and commercial cities.

Bibliographie

24

Adem, T. A., Ember, C. R., Skoggard, I., Jones, E. C., & Faas, A. J. (2012). Dangerous geography: Spatial distribution of livestock raiding in north-western Kenya. Ethnology, 1-29.

Adesoji, A. O. (2011). Between Maitatsine and Boko Haram: Islamic fundamentalism and the response of the Nigerian state. Africa Today, 57(4), 98-119.

Aghedo, I., & Osumah, O. (2012). The Boko Haram uprising: how should Nigeria respond? Third World Quarterly, 33(5), 853-869.

Assouga Calvin Minfegue (2018). « Les frontières camerounaises entre héritages historiques et contestations nouvelles », Revue des sciences sociales, 60 | 2018, 26-35.

Ayana, E. K., Ceccato, P., Fisher, J. R., & DeFries, R. (2016). Examining the relationship between environmental factors and conflict in pastoralist areas of East Africa. Science of The Total Environment, 557, 601-611.

Bandyopadhyay, S., Sandler, T., & Younas, J. (2010). Foreign aid as counterterrorism policy. Oxford Economic Papers, gpq030.

Bayart, J.-F., 1979. L’Etat au Cameroun. Presses de la Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques.

Benantar, Abdennour (2016). « Sécurité aux frontières : Portée et limites de la stratégie algérienne », L’Année du Maghreb, 14 | 2016, 147-163.

Bensassi, S., Brockmeyer, A., Pellerin, M., & Raballand, G. (2015). Commerce Algérie - Mali : la normalité de l’informalité. Retrieved from Washington D.C.:

Bigo, D. (2011). Frontières, territoire, sécurité, souveraineté. Durand Marie-Françoise, Lequesne Christian. Ceriscope Frontières, Sciences Po - CERI, pp.1-13.

Blanchard, L. P. (2014). Nigeria's Boko Haram: Frequently Asked Questions. Current Politics and Economics of Africa, 7(2), 143.

Botha, A. (2014). Radicalisation in Kenya. Recruitment to al-Shabaab and the Mombasa Republican Council.

British Army, 2009. British Army Field Manual Volume 1 Part 10 Countering Insurgency.

Brown, S., & Grävingholt, J. (2016). The Securitization of Foreign Aid: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

CAD, O. (2003). Inscrire la coopération pour le développment dans une optique de prévention du terrorisme : principaux points d'ancrage pour l'action. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=DCD/DAC(2003)11/REV1&docLanguage=Fr

Cantens, T., & Raballand, G. (2017). Cross-Border Trade, Insecurity and the Role of Customs: Some Lessons from Six Field Studies in (Post-) Conflict Regions.

Charbonneau, B. (2017). « De Serval à Barkhane : les problèmes de la guerre contre le terrorisme au Sahel ». Les Temps Modernes, 693-694,(2), 322-340. doi:10.3917/ltm.693.0322.

Cohen, C. (2015). « Boko Haram, une impossible sociologie politique : Un groupe armé catalyseur de la violence armée régionale ». Afrique contemporaine, 255,(3), 75-92. doi:10.3917/afco.255.0075.

Deléchat, C., Fuli, E., Mulaj, D., Ramirez, G., & Xu, R. (2015). Exiting From Fragility: The Role of Fiscal Policies and Fiscal Institutions. In (Vol. WP/15/xx): International Monetary Fund.

next...

25

Desgrais, N. (2018). La Force conjointe du G5 Sahel ou l'émergence d'une architecture de défense collective propre au Sahel. Les Champs de Mars, 30 + supplément,(1), 211-220. https://www-cairn-info.sicd.clermont-universite.fr/revue-les-champs-de-mars-2018-1.htm-page-211.htm.

Duez, D. & Simonneau, D. (2018). Repenser la notion de frontière aujourd’hui. Du droit à la sociologie. Droit et société, 98,(1), 37-52.

Eizenstat, S. E., Porter, J. E., & Weinstein, J. M. (2005). Rebuilding weak states. Foreign affairs, 134-146.

Foyou, V. E., Ngwafu, P., Santoyo, M., & Ortiz, A. (2018). The Boko Haram Insurgency and its Impact on Border Security, Trade and Economic Collaboration Between Nigeria and Cameroon: An Exploratory Study. African Social Science Review, 9(1), 7.

Frowd, P. M., & Sandor, A. J. (2018). Militarism and its limits: Sociological insights on security assemblages in the Sahel. Security Dialogue, 49(1-2), 70-82.

Giblin, B. (2018). Rapports de force et conflits frontaliers. Pouvoirs, 165,(2), 89-98. doi:10.3917/pouv.165.0089.

Gilbert, E. (2015). Money as a “weapons system” and the entrepreneurial way of war. Critical Military Studies, 1(3), 202-219.

Grégoire, E. (2018). Frontières étatiques, frontières mobiles et rentes frontalières dans l’espace saharo-sahélien. L'Information géographique, vol. 82,(1), 82-98. doi:10.3917/lig.821.0082.

Hadley, L. A Spatial Theory of Civil Conflict in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Hanne, O. (2017). L’opération « Barkhane » devant l’évolution des risques dans la Bande sahélo-saharienne. Outre-Terre, 51,(2), 225-237. doi:10.3917/oute1.051.0225.

International Monetary Fund (2017). Cameroon. Country Report 17/185.

International Monetary Fund (2018). Regional Economic Outlook, April 2018, Sub-Saharan Africa : Domestic Revenue Mobilization and Private Investment.

JCS -Joint Chiefs of Staff (2018). Counterinsurgency JP-3-24.

Ladbury, S., Allamin, H., Nagarajan, C., Francis, P., & Ukiwo, U. (2016). Jihadi Groups and State-Building: The Case of Boko Haram in Nigeria. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development, 5(1).

Lori-Anne Théroux-Bénoni, W. A., Ibrahim Maïga, Jeannine Ella A Abatan, Fatimata Ba, Patrick Olivier Gnonsekan, Aïssatou Kanté, Kadiatou Yacouba Keïta, Wendyam Aristide Sawadogo – along with Modibo Galy Cissé, Aboubacar Diallo, Bréma Ély Dicko, Amadou dit Samba Cissé, Yacouba Dogoni, Fodié Tandjigora and Aly Tounkara. (2016). Mali's young 'jihadists': Fuelled by faith or circumstance? Retrieved from https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/policybrief89-eng-v2.pdf

Magrin, G., de Montclos, M. A. P. (2018). La région du Lac Tchad à l’épreuve de Boko Haram. Crise et développement, 75.

Marchal, R. & Ould Ahmed Salem, Z. (2018). La « radicalisation » aide-t-elle à mieux penser ?. Politique africaine, 149,(1), 5-20. doi:10.3917/polaf.149.0005.

Onuoha, F. C. (2013). Porous borders and Boko Haram’s arms smuggling operations in Nigeria. Al Jazeera Center for Studies, 8.

Perito, R. M. (2015). UN Peacekeeping in the Sahel.

Raleigh, C., Witmer, F., O’Loughlin, J., & Denemark, R. A. (2010). A review and assessment of spatial analysis and conflict: The geography of war. The international studies encyclopedia, 10, 6534-6553.

Schutte, S., & Weidmann, N. B. (2011). Diffusion patterns of violence in civil wars. Political Geography, 30(3), 143-152.

Seignobos, C. (2014). Boko Haram: innovations guerrières depuis les monts Mandara. Afrique contemporaine(4), 149-169.

Serrano, R., & Pieri, Z. (2014). By the numbers: the Nigerian State's efforts to counter Boko Haram. In M.-A. Pérouse de Montclos (Ed.), Boko Haram: Islamism, Politics, Security and the State in Nigeria (pp. 192-212): Tsehai Publishers & Distributors.

Van Den Hoek, J. (2017). Agricultural market activity and Boko Haram attacks in northeastern Nigeria.

Waddington, C. (2014). Boko Haram makes its presence felt in Cameroon: West Africa-issue in focus. Africa Conflict Monthly Monitor, 2014 (Sep 2014), 48-52.

Walther, O. (2018). Villes-frontières et réseaux informels sahéliens (Gaya-Malanville-Kamba). Geographica Helvetica, 62 (1), 33-42.

next...

http://www.antiatlas-journal.net/pdf/03-cantens-fragile-borders-in-subsaharian-africa.pdf

Notes

26

1. Boko Haram, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and Islamic State in the Greater Sahara are currently the main "labels" of these armed groups which may change name but which all call to insurgency based on religious views.

2. See Blanchard (2016) for the American Congress.

3. See the evolution of Boko Haram in Appendix 1.

4. The cost of the war against Boko Haram for Cameroon between 2014 and 2016 is estimated at 1% of annual GDP (IMF 2017). In its document on revenue mobilisation, the IMF (2018) assesses the direct and indirect impacts on the budgets of Sahel countries affected by terrorism.

5. Although military action in the Sahel Region is particularly visible in the public sphere, "security" programmes aiming to develop non-military bureaucratic apparatuses are equally important (Frowd and Sandord, 2018) and support for economic activities is part of the counter-insurgency operations as theorised by the US and British armed forces (Gilbert 2015). Military operations such as Barkhane or MINUSMA include a civil and "humanitarian" component (with the Quick Impact Projects). However, these programmes must be assessed by their funding: the annual costs of French or United Nations operations are of the order of 300 million to 1 billion Euros per country, far from the funds devoted to humanitarian action. In Mali, public development aid was USD 600 to 700 million per year between 2014 and 2017 (source OECD, DAC2a). National budgets are also sometimes below the peace-keeping budget. As for counter-insurgency operations, the American "manuals" clearly refer to very short-term support rather than long-term involvement (JCS 2018, British Army 2009).

6. The missions took place in Somalia, Libya (Tripoli and border with Tunisia), Tunisia (Ben Gardane and border with Libya), Jordan (border with Syria), Mali (Timbuktu and Gao), Burkina Faso (north-eastern regions), Niger (Diffa region), Nigeria (Borno state), Chad (Lake Chad), Sudan (Darfur) and Central African Republic (north-east).

7. In Somalia, the zones were the three ports, Mogadishu, Bosaso and Kismayo.

8. Unless otherwise specified, all raw data on incidents are extracted from the ACLED Armed Conflict Events Location Database (Raleigh and al. 2010, www.acleddata.com).

9. In particular, research was done within the framework of the "Sécurité Par Collaboration" security project initiated by customs of Nigeria, Central African Republic, Chad, Cameroon and Niger in 2016, joined by those of Mali and Burkina Faso in 2017 and 2018.

10. See Serrano and Pieri (2014) on considering Boko Haram as an insurgency, in all its dimensions, rather than reducing the group to "terrorists", without denying that terrorism is adopted as a strategy.

11. It is impossible to cite the number of articles containing the phrase "porous border" because there are too many and the expression has become commonplace in connection with African borders.

12. In peaceful border areas, Walther (2018) has shown how, through trade, border towns maintain local ties often neglected by public policies which focus more on a national level.

13. The "political dimension" is not reduced to managing the economy, it also relates to "social values", ideology and its negation by states. See Adesoji (2011) and Aghedo and Osumah (2012) for Nigeria, Marchal and Ould Ahmed Salem (2018) on the role of religion in the deterioration of relations between the government and the population. Cohen (2015) notes the absence of the notion of state from his talks with inhabitants in Nigerian towns affected by Boko Haram. Again in the Lake Chad area, Magrin and de Montclos (2018) report on the "corruption, the deficiencies of the government, the brutality of military repression and the harm it causes in the civilian population [as] key factors of the insurgency and its prolongation." (p. 10). Ladbury et al. (2016) thus compare Boko Haram's apparent lack of political strategy with the strategies of other Jihadist groups.

14. Data available from 2010 for Nigeria, Niger, Mali, Central African Republic, Chad and Cameroon. The border areas have been delimited based on the "range of action of customs" and an economic definition of border including the part of the territory whose economy is structured by the border (trade routes and centres).

15. A former Boko Haram militant explained during an interview how some members of the group were authorised to leave the territory and do business.

16. Following talks with former members of the Boko Haram group.

17. Not all are peaceful or aimed at development, such as, for instance, holding a merchant's family hostage while he carried out transactions for the armed group (Boko Haram).

18. Bayart (1979).

19. These suspicions resulted in looting when the town was freed (https://www.france24.com/fr/20130221-reporters-mali-tombouctou-islamistes-fondamentalistes-al-qaida-touaregs-arabes-france24).

20. Discussions with Tunisian customs officers in 2016.

21. Discussions with Libyan customs officers in 2017 in Tripoli and Zwerat (Libya).

22. Talks with senior members of the tax authority of Jubaland State and figures collected from merchants by those agents in 2018.

23. Talks with merchants and carriers from the north of the Central African Republic in 2017.

24. Talks with customs officers and merchants in Bol and N’Djamena (Chad) in 2016.

25. Talks with merchants and carriers in various border towns in northern Burkina Faso in 2018. In 2019, it seems that the situation is changing in the Lake Chad area, where one Boko Haram fraction is levying a tax on cattle, in kind and an equivalent rate that is lower than the official Customs rate. Part of this revenue is sold on local markets. In the past, a similar tax was levied by a Boko Haram fraction on fish trade, which constrained the Nigerian authorities to close the Maiduguri fish market, with partial success (field observation in 2018).

26. It is difficult to know whether the carriers were telling the truth. However, the fact that they were talking to a foreign observer shows that they did not want to portray the religious armed groups as simple bandits. Furthermore, stories recounting that no violence was inflicted on the merchants were collected from various sources.

27. http://malijet.com/a_la_une_du_mali/121613-attaques_de_tenenkou_l_ombre_de_hammadoun.html; http://bamada.net/mopti-face-a-linsecurite-le-pouvoir-djihadiste-de-plus-en-plus-ferme-et-incontestable-au-centre-du-mali; http://www.malinet.net/alerte/hamadoun-koufa-etend-son-autorite-a-degimbere-les-hommes-interdisent-taxes-et-impots/

28. Talks with merchants in numerous areas.

29. Talks with merchants from Maiduguri, Geidam and Gamboru (Nigeria), Diffa (Niger) and Fotokol (Cameroon) between 2017 and 2018.

30. Talks with merchants from Bol (Chad) on the banks of Lake Chad, 2017.

31. See, for example, Bensassi et al. (2015) on the "normality of informality" at borders.

32. Benantar (2016) recalls the multiples "regional" security initiatives and their weak results. Among them, Desgrais (2018) reports on the relative failure of CEMOC (Joint Operational Army Staffs Committee), an Algerian regional cooperation initiative which intended to carry out joint border patrols. Although this measure was never operationally implemented, the CEMOC did serve as a training institution for senior officers of the armed forces in the region.

33. For the G5 Sahel joint force, the border area is a 50km strip in which there is a right of pursuit. This definition does not encompass the economic customs perspective, where the border area includes the trade hubs, i.e. the urban centres whose economy depends on cross-border trade. Customs officers need to know the limits within which the border economy shapes the territory, via roads, urban centres, and storage or transhipment areas. Customs officers have intuitive knowledge of this structure which should be documented on a map.

34. The trial of the geographic information system COMPSTAT by the American police force was studied from this viewpoint: the map as an interface between different professions.

35. These thoughts were technically developed and partly implemented in the context of the Sécurité par Collaboration (Security by Cooperation) security project.

> Back to the top of the article